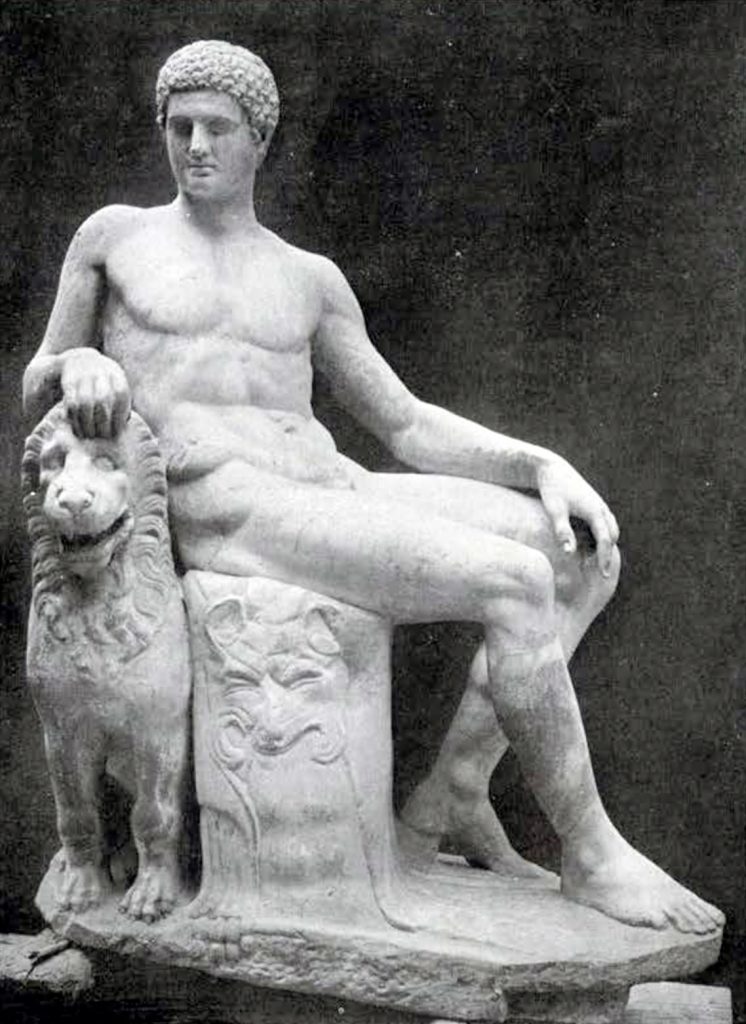

The last addition to the Lucy Wharton Drexel collection of Roman sculpture acquired only a short time before the death of the donor is a life-sized marble statue representing a nude figure of a man seated on a rock over which a panther’s skin is spread, and resting his right arm on the head of a lion, Fig. 142. It was procured from a dealer in Rome into whose hands it had passed after being sold at public auction by the Nazarene College, which, according to report, had acquired possession of it in 1622 at the time they inherited the Palazzo dei duchi Caetani. At some period of its history the statue had been built into a fountain; to serve this purpose passages had been bored from the nape of the lion’s neck through the mouth and from front to back straight through the human torso. To this vandalism is doubtless due the fact that both jaws of the lion have been broken, the upper so badly as to entail the restoration of the nostrils and left cheek, and also the fact that the shoulders and back of the torso are somewhat eroded by water.

The other restorations which the statue has undergone include the head, the thumb and forefinger of the left hand, the big toe of the right foot, and two portions of the right leg where ancient pieces had been rejoined. The method by which this mending was done as well as the style of the restored head indicate that the restorations may date from so early a period as that of the renaissance.

Museum Object Number: MS5483

Image Number: 10857

With the exception of these restored parts, the entire statue, including both the lion and the rock, is made from a single block of fine white marble which shows in places the yellow tinges of oxidation. The workmanship of the statue is uneven; the modeling of the torso is good, that of the arms and feet and especially that of the lion’s legs is poor. A possible explanation is that a less skilful artist was given the incomplete work of his superior to finish, or it may be that a mutilated original was at hand for the sculptor to copy so that while working on the torso he had a model to guide him, whereas when fashioning the arms and feet he was obliged to rely upon his own unaided powers.

Seated figures of the gods are common in Greek sculpture from the early archaic period. Among the pre-Persian marbles from the Akropolis, on the frieze of the Knidian Treasury at Delphi, are found seated figures of deities. But it was in a somewhat later period of Greek art that there was evolved this particular type of statue, that of a god seated on a rock, one foot extended, one drawn beneath him and the whole attitude expressive of weariness. Three gods in particular are so depicted, Hermes, Herakles and Dionysos, and the question arises as to which of these deities is here represented.

The type of seated Hermes is perhaps the most familiar; in the Museum is a copy of the Herculaneum bronze representing Hermes seated on a rock, his right foot extended, his left drawn beneath him in an attitude quite similar to that seen in Fig 136. Still more closely analogous to this statue is one in the British Museum; the god in this case rests his left arm on a rock beside which is a cock. But a cock belongs to Hermes, whereas neither a lion nor a panther’s pelt are numbered among his attributes.

The lion suggests Herakles and in general the statue presents analogies to the colossal statue in the Palace Oldtemps in Rome, recently reproduced in the Brunn-Bruckmann plates, but here the hero sits, as would be expected, upon a lion’s skin, not upon that of a panther. He carries, moreover, a club which makes his identification sure. Whether other attributes than the lion’s skin are essential is doubtful; a statuette of Herakles, now lost, that known as the Hercules of Feurs, apparently represented the god with no other attributes than the lion’s skin on which he was sitting. But that Herakles should be seated on any other kind of a skin than that of a lion seems incredible.

And what of Dionysos? The panther’s skin suits him entirely, but the lion at the side of the seated figure does not suggest the god of wine. The presence of the lion seems all the more strange in view of the fact that there is in Florence a statue very closely analogous to this one. It represents a seated figure in precisely the same attitude, the right foot extended, the left drawn beneath him, the left hand resting on the thigh and the right shoulder raised by the position of the arm, which in this case, however, is held not above a lion but above a panther. How can the presence of a lion instead of a panther be explained? We learn that in the course of the development of the Dionysiac cult, new symbols were joined to Dionysos which had originally belonged to the oriental gods assimilated by him. Among these was the lion, which, it is now thought, was borrowed not from the Phrygian Cybele but from the Lydian Bassareus. The shifts in religious beliefs and the influence of one cult upon another are generally faithfully reflected in vase-paintings, so that it is to vases one must turn for proof of the association of the lion with Dionysos. Such proof is not wanting; on a black-figured kylix dating from the sixth century is a picture of Dionysos holding a kantharus above the head of a lion who sits apparently in eager expectation of a share of its contents.*

On another well-known kylix in Würzburg, Dionysos appears in a chariot drawn by a panther, a lion and two deer. This association of the lion with Dionysos in vase-paintings and the close correspondence of the statue illustrated in these pages with the Florence statue which certainly represents Dionysos, warrants, I believe, the theory that the former reproduces an old type of Dionysos statue in which the lion has been substituted for the panther.

It remains to determine the date of this statue, a problem which involves both the fixing of the date of the Greek original and that of the Roman copy, for there is nothing about either the workmanship or style of the marble in the Museum to indicate that it is itself a Greek original. The probability is that it is one of those numerous statues made to adorn the villas or gardens of wealthy Romans of the early empire. Such Roman copies, frequently repeated and freely modified, though they may not be taken to reproduce accurately the Greek types from which they are descended, are yet of great importance to the student of sculpture for determining what those types were. The originals are lost, but the copies remain and reflect, if but dimly, the conceptions of the Greek masters.

The original type of seated Dionysos from which the statue in the Museum is derived goes back to the fourth if not to the fifth century B. C. The beautiful monument of Lysikrates in Athens erected in 335 B. C. to commemorate a choregic victory is adorned with a frieze which depicts in low relief the punishment administered to the Tyrrhenian pirates by Dionysos. Here the god appears seated on a rock in an attitude not unlike that of the statue to which we call attention and there is a chance that this type of seated Dionysos may have an even earlier origin. We have already noted the resemblance of the statue to that of Herakles in the Palace Oldtemps in Rome. The original of this statue has been traced to Myron and it is entirely possible that the seated Dionysos type was derived from that of the seated Herakles or that it was itself invented in as early a period as that of Myron.

E. H. H.