OF all the hybrid creatures, half man and half beast, which are represented in ancient art, the most famous is the sphinx. Such mythical creatures are numberless and are common to the art of Mesopotamia, to that of Egypt, and to the Mediterranean area generally. One has only to recall the Minotaur of Crete, the centaurs of Greece, the Cherubim of the Hebrews, the winged bulls of the palace of Sargon at Khorsabad, and the strange gods of the Egyptians, to realize how manifold and widespread these monstrous forms were. In Egypt, from a remote era, a favorite combination was that which united the body of a lion with a human head. That this form had become firmly established at the time of the Old Kingdom, is shown by the great sphinx of Gizeh, and although many other types of sphinxes were known to Egyptian art, such as the sitting sphinx, the sphinx with a woman’s head, or the sphinx trampling his enemies, the type made famous by the great sphinx at Gizeh remained always the most popular. To the sphinx of Greek legend, whose riddle was solved by Oidipous, this type stands in marked contrast; the Greek sphinx is represented in a sitting position, is winged, and has the head of a woman, whereas the Egyptian type is wingless, is represented in a lying position, and has the head of a man.

Image Number: 173851

The Egyptian sphinx, moreover, had a significance entirely different from that of the Greeks, for it was, as a rule, nothing but a portrait of a reigning Pharaoh with the body of a lion, which implied that the king was represented in his capacity of guardian. Occasionally it was a god who was thus represented, as at Abusir, where the god Sopt was depicted in the form of a sphinx. The later Egyptians of the New Empire regarded the great sphinx at Gizeh as the statue of a god, but they were mistaken; modern scholarship has shown that it.Was in reality a portrait of Chephren, the builder of the second pyramid and of the valley-temple by which the sphinx stood.

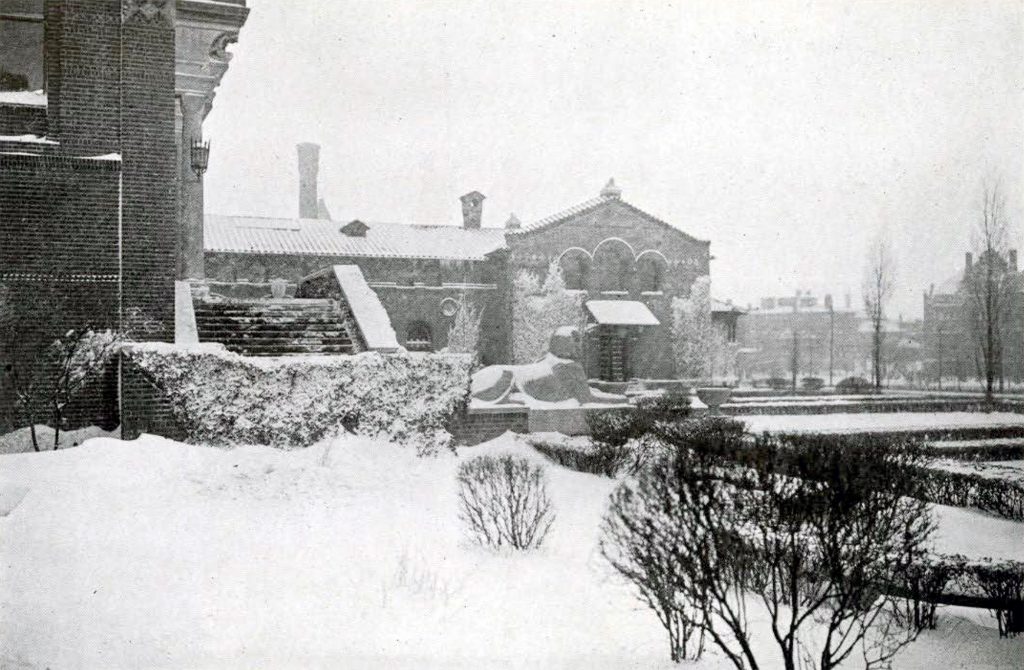

In 1912 within the great temenos of the god Ptah at Memphis, a red granite sphinx was found by the English excavators of the British School of Archeology in Egypt. A granite dyad of Rameses II and Ptah, found at the same time, was granted to the Ny Carlsberg Museum at Copenhagen; the sphinx was acquired for the University Museum. It reached America in the autumn of 1913 and was set up temporarily in the courtyard of the museum. It is a colossal piece of sculpture measuring twelve feet seven inches one way and three feet nine and one half the other. The surface of the granite is beautifully preserved except for the head and a part of the back which, unfortunately, remained exposed after the rest of the statue had become covered with debris. Thus the face is badly weathered, whereas the cartouches and inscriptions on the base have edges as sharp as on the day they were cut.

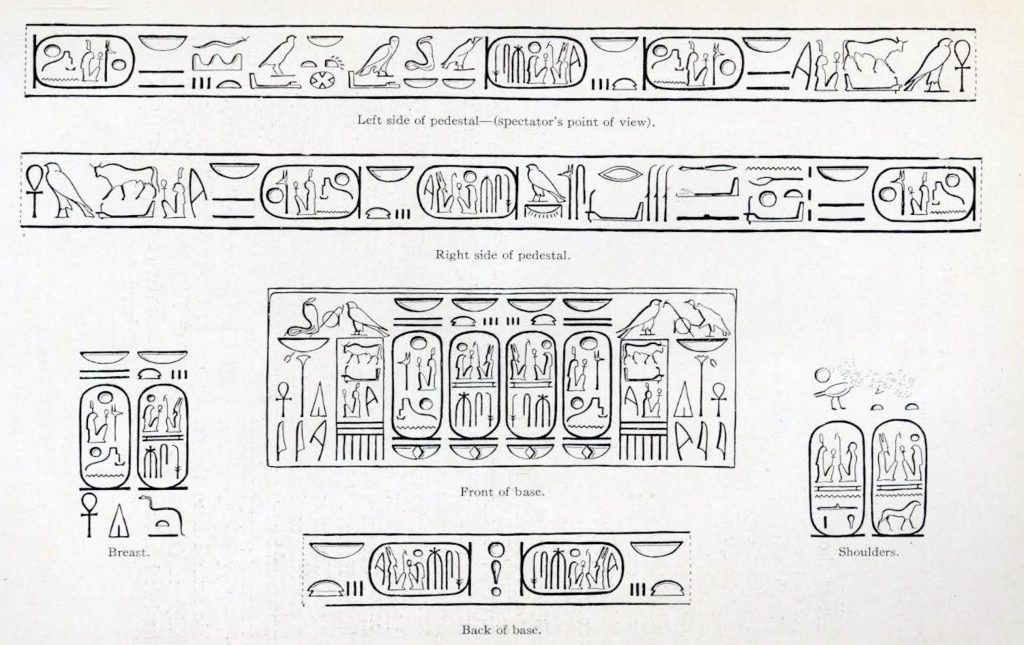

The inscriptions show that this sphinx, according to the general rule, was the portrait of a Pharaoh and that the Pharaoh represented was Rameses the Great. They consist merely of epithets and of titles of the kind so familiar from the long series of monuments erected by this famous king to commemorate his own achievements. Dr. Caroline L. Ransom has kindly contributed the translations of these inscriptions which read as follows.

Museum Object Number: E12326

LEFT SIDE OF PEDESTAL (spectator’s point of view).—Inscription written from right to left: “Live the Horus, Mighty Bull, Beloved of Truth, Lord of the Two Lands, Usermare-Setepnere, Lord of Diadems, Meriamon-Ramessu, Favorite of the Two Goddesses, Defender of Egypt, Binder of the Foreign Lands, Lord of the Two Lands, Usermare Setepnere.”

RIGHT SIDE OF PEDESTAL.—Inscription written from left to right: ” Live the Horus, Mighty Bull, Beloved of Truth, Lord of the Two Lands, Usermare-Setepnere, Lord of Diadems, Meriamon-Ramessu, Golden Horus, Mighty in Years, Great in Victories, Lord of the Two Lands, Usermare-Setepnere.”

FRONT OF BASE.—Inscription arranged symmetrically. The two central cartouches both read: ” Lord of Diadems, Meriamon-Ramessu “; the next two, second from the center on each side, read: ” Lord of the Two Lands, Usermare-Setepnere.” Then on each side second from the corner, occurs the so-called “Banner name ” which reads: ” The Horus, Mighty Bull, Beloved of Truth.” At the left hand corner, we have: “Beloved of the Goddess of Lower Egypt, given life”; at the right hand corner: “Beloved of the Goddess of Upper Egypt, given life.”

BACK OF BASE.—Arranged symmetrically and read from corners (not from center as in inscription on front of base), the central group, “like Re” being read twice. This reads: ” Lord of Diadems, Meriamon-Ramessu, like Re.”

Image Number: 153320

ON BREAST OF SPHINX. Two cartouches arranged symmetrically, that is, the signs face towards the center and the one at the right is read from the left and the one at the left from the right. On right, “Lord of Diadems, Meriamon-Ramessu “; on the left, “Lord of the Two Lands, Usermare-Setepnere.”

ON SHOULDERS OF SPHINX.—Two cartouches of Merneptah, the successor of Ramses II, therefore, of course, added subsequently to the original inscriptions. The cartouche to the front on each side reads: “King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Binre-Meriamon” ; the cartouche to the hack: “Son of Re, Merneptah-Hotephirma.” The same symmetrical arrangement for decorative effect is observed as in the cartouches on the breast of the sphinx.

As typical of the spirit of Rameses II and the nineteenth dynasty (1350-1205 B. C.) this monument has no little historical value. Yet its chief interest will doubtless be as a work of art, for it has those qualities of style which characterize the greatest work of Egyptian sculpture, a rigid exclusion of unessential details, a feeling for decorative effect both in the composition and in the treatment of separate parts, and that immobile quiet which belongs to monuments in stone.

E. H. H.