This is Part 3 of 4 of The Alexander Scott Collection article, which has been divided into sections for clarity.

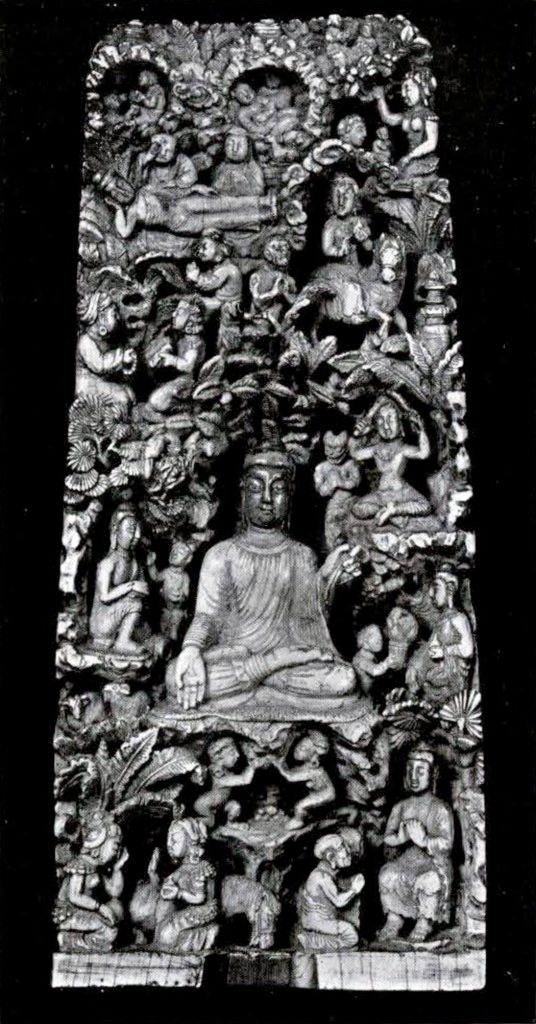

The carving is executed in a section of elephant’s tusk fashioned into a tablet. It is arranged in medallions, representing some of the episodes in the life of Buddha-Gautama-Sakya-Muni. At the first glance it presents an artistic and skilful arrangement of forms so intricate as almost to repel study, but no known specimen of Oriental art better deserves the very closest attention. This may he stated for many reasons, amongst which, priority I think should be given to the fact that it depicts an early and pure form of the Buddhist faith which has for centuries been almost lost sight of. Upon it, what have been called the parallels in the Life of Buddha and the Gospel of St. Luke are strikingly in evidence. These parallels have been made much of by sceptics, but must not be pushed too far. Nevertheless, it is strange to find in this ancient carving, more than a hint of the Annunciation; of the Divine Message; of the dispute with priests of a rival faith; of the wayside supplication and of the Temptation in the Wilderness. Another point of great interest lies in the question as to what Christian art owes to Buddhism. Modern opinion agrees that it owes much and this old relic of the past helps to prove it. Look for instance at the top of the tablet, where, in the center, is a representation of the birth of Buddha. It is enclosed by pastoral emblems, among which are seen sheep and hares. Do not these recall the pictures of the Nativity by painters of the Renaissance? Look at the plinth or foundation of the large figure of Gautama in meditation under the sacred bohdi-tree in the cave of Budh-Gaya; you will see that it is supported by two cherubs. Do not these recall the design of the holy water receptacles of St. Peter’s at Rome.

As in Christian art there have been changes from realism to idealism and back again to realism, so have archaeologists revealed the history of Buddhist art to us. They have taught us that there was, co-existent with the early teaching of this faith, a genuine love and worship of nature. Turn to this tablet again and observe the love and appreciation of nature which guided the hand that carved the leaves, the birds in their nests and the tiny animals. Note the natural lines of the draperies and even the expressions of the faces. Look at Ananda, the beloved disciple, sitting with his master in the cave trying not to laugh whilst a demon is tickling his ear with a feather. And this again is a very special point of interest, for humor has no place in Indian art. That art is devoted wholly and solely to sacred purposes and with this single exception I have never seen an instance to the contrary.

It may well be asked, who made this ivory tablet. Where and when was it made? My own belief, confirmed by lamaistic traditions and what is known to the archaeological world of the history of Indo-Buddhist art is that it was made by an Indian, probably in Kamrup (Assam) at the old city of Gauhati, possibly in the fifth or sixth century A.D. Whoever he may have been, it is certain that he must have been a Buddhist of the old faith who knew nothing of the later developments and symbolisms. The lamas themselves with whom I talked are certain that it is very much older and say that it would quite inevitably have been designed on an entirely different plan with many added features if it had been made later than King Asoka’s time (250 B. C.) which was when the gates of Sanchi were made. Almost in corroboration of this, Professor Vincent Smith, the famous archaeologist, remarks that “the art of Asoka’s time was characterized by frank naturalism, thoroughly human, a mirror of the social and religious life of ancient India,” and he adds, “apparently a much pleasanter and merrier life than that of the India of later ages,” and furthermore that “the ancient Indian artists, like Cellini and the other great craftsmen of the Renaissance, were able to turn from one material to another without difficulty. Similar versatility was displayed by the Bhilsa ivory carvers, who executed some of the stone reliefs at Sanchi and by still earlier craftsmen, who readily applied to stone the skill previously acquired in working materials of a less permanent kind.” (No. 1162.)

Museum Object Number: A1162

Image Number: 2340

ANTIQUE CRYSTAL BUDDHA ON PEDESTAL WITH SYMBOLICAL SCREEN (Fig. 30).—This is, so far as can be ascertained, the only Indian crystal statuette of Gautama known to collectors. It came from Tibet, but was probably made at Gauhati, Assam, over a thousand years ago. This is the belief of the lamas. There is a Buddha of crystal in the temple of the Sacred Tooth at Kandy, Ceylon, but it is of Chinese make and comparatively modern. (No. 1116.)

CHUNGA OR PORTABLE BARREL FOR MURWA BEER (Fig. 31), brewed from the fermented juice of millet seeds. In general use in Tibet, Butan and Sikim. This is an exceptional specimen, the rich ornamentation being fine old Nepalese repousse or hammered work. Eighteenth century. (No. 1165.)

LIBATION CUP of rhinoceros horn, bearing ten plaques outside and one inside, carved in relief and representing the Hindu Pantheon from a Nepalese Temple. Spoon used with it, copper. Nepalese workmanship. Eighteenth century. (No. 1131.)

FIGURE OF DÖLMA OR TARA (Fig. 32).—She is the Tutelar goddess of the established church of Tibet, the Gelukpas. She is the personification of divine charity and protection. She is said to be inviting all the wise and righteous to a feast of divine wisdom, with her right hand extended, saying, “Come and partake.” With her left hand she holds the lotus of immortal rebirth and makes the sign of the Trinity with her fingers saying, ” Fear not, come and I will protect. I am the manifestation of the three in one. I will protect now and give you immortal birth hereafter,” symbolized by the lotus. She is the combined form of all the merciful, attractive, loving and lovable attributes of the Cause of all Causes. The attitude of her feet is called the Bodhisattvic Asan or posture of Bodhisattvas.

She sits upon the throne of double petalled lotuses, meaning that she is an eternal and immortal being herself and is able to give eternal life unto others.

She is fully dressed and most beautifully adorned with jewels, meaning that she is perfect from every point of view.

She is surrounded by a halo of rainbow light, meaning that she dispels the darkness of ignorance and bestows the beauty of wisdom and enlightenment. (No. 1123.)

A. S.

Museum Object Number: A1116

Image Number: 2165

Museum Object Number: A1165

Image Number: 2182

Museum Object Number: A1123

Image Number: 2175