In 1886 word was brought to the authorities in Candia that peasants of the Lasithe plain in eastern Crete had discovered a number of bronze offerings in the Dictæan cave where they were in the habit of housing their pigeons and goats. That this cave was regarded as a holy place in antiquity was known from the literature of the classical period; here, according to legend, Zeus was born; here Europa was brought by Zeus; and here Minos, the offspring of their union, found the code of laws which he delivered to the people of Crete. The news of the peasants’ discovery brought several archaeologists to the site, but no systematic search was made until June, 1900, when Mr. David Hogarth, then director of the British school at Athens, undertook the excavation of the cave. In a stratum of black earth which covered the floor of the grotto, along the margins of the icy pools within its deep recesses, and even in the crevices of the stalactite columns in which the cave abounded, were found numerous votive offerings of bronze and of terra-cotta. “The villagers, both men and women, worked with frantic zeal, clinging singly to the pillars high above the subterranean lake or grouping half a dozen flaring lights over a productive patch of mud at the water’s edge.”

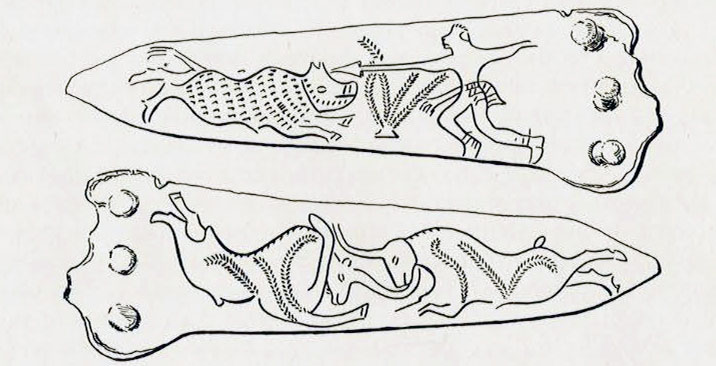

The rich deposits of the cave were not, however, exhausted. Bronze knives and pins, bone needles, and other small objects continued to be found; sometimes these came under cognizance of the authorities and were carried to the museum at Candia, but oftentimes the peasants succeeded in eluding the vigilance of the gendarmes stationed at the mouth of the cave and, entering by night into its cavernous depths, carried on their illicit search. One of the most interesting objects ever found in the cave, a bronze blade with incised designs, was thus discovered by peasants during the past year. It was brought in course of time to America, and is now in the hands of a private collector. Drawings made from the original are shown in Fig. 91 and a cast of the blade has been put on exhibition at the Museum.

The specimen is unique. The nearest parallel is afforded by the inlaid daggers from the shaft-graves of Mycenae, which are, of course, much more elaborate in technique as well as more beautiful in decoration. With the exception of these daggers from Mycenae, blades ornamented with engraved designs have been exceedingly rare. The scenes, moreover, which are engraved on this blade, a boar-hunt and a bull-fight, are new to Cretan art.

The blade is six inches long and is covered with a beautiful smooth green patina. The three bronze rivets which fastened it to the hilt are still in place. They were apparently silver-plated, for traces of silvering may be detected on one of them. The shape of the blade is not characteristic of any particular period of Cretan metallurgy. Very similar blades were found at Mochlos in tombs which could be assigned to an early stage of Cretan art (the Middle Minoan I period). But the shape is not unknown in later periods and to a later period (Late Minoan III) it may best be assigned on the ground of the style of the designs.

Museum Object Number: MS5382

Since the blade was found in a holy place, filled with votive offerings, the presumption is that it also is a dedication, commemorative of a successful exploit. The hunter in the scene may therefore be plausibly regarded as the donor himself. He is represented in the very act of killing his boar, his spear firmly held in both hands to meet the shock of the animal’s onrush. The out-door world is indicated by the simple expedient of introducing a tuft of fern-like sprays between the hunter and his victim, The boar is charging at full speed, his legs extended and his tail flying in the air. The tail, which ends in a kind of tassel, gives a hint as to the kind of loin-cloth worn by the hunter. It is apparently of skin, for a tasseled end precisely like the boar’s tail hangs down in front. His only other articles of dress are boots which were fastened with thongs tied behind. The head of the man is indicated in the most cursory fashion; it consists mostly of nose and ear with a small fringe of hair above and a slight tuft of beard. His left arm, moreover, is not distinguished from the spear; either the artist was less interested in the picture of himself, or else he found the difficulties of rendering the human form much more perplexing than those of rendering a boar.

The scene recalls the fresco portraying the killing of a boar which was found recently in the later palace of Tiryns, but here, as in the case of a gem published in Furtwaengler’s Antike Gemmen (Pl. II, 12), the thrust of the spear is delivered with a downward stroke. The level stroke here depicted, which would hardly more than brush the boar’s ears, must be attributed to the lack of skill on the part of the artist. This is the first complete picture of a boar-hunt to be found in Cretan soil. Boars have appeared before as designs for seal-stones and as signs in the pictographic script, and there are fragments of scenes in which boars figured, as a fragment of a steatite vase from Palaikastro and a piece of a painted vase from the Dictæan cave which belongs to the last phase of Cretan art and is only slightly later in date than the bronze blade.

The scene on the other face of the blade depicts the critical moment of an exciting bull-fight. The bull on the left is represented in a tortuous position with his left foreleg raised in air between his head and right foreleg. He is evidently in for a bad fall and is getting the worst of the fight. The fact that one of his horns is represented just below the neck of the other bull does not mean that he has succeeded in dealing a death blow to his opponent, but merely that the artist found here convenient space for showing the long horn of the bull. The fern pattern which occurs in the tuft of plants in the other scene appears here on the bodies of bulls. At first sight its presence seems due to the same confusion of decorative and representative art which led the artist of the vase fragment from the Dictæan cave to end the tail of his boar in a tuft of flowers. It is more likely, however, that the artist was attempting to indicate the furry lines of the bulls’ coat where the direction of the hair changes. This is the more likely because on a fresco from Tiryns representing shields covered with bulls’ hides, the dorsal line of the hide is indicated in a manner only a little less stylized than this. The predilection of the Cretan artists for bulls has been satisfactorily explained by the supposition that the national sport of the early Cretans was bull-grappling. The less frequent scenes of bull-trapping and this exceedingly rare scene of bulls fighting may be regarded as pictures of mere incidents in the life of an arena which was given over to contests of bulls and men.

E. H. H.