Mr. Clarence S. Fisher, Curator of the Egyptian Section of the Museum, arrived in Egypt on December 16, 1914. On that day, as it happened, Egypt became a Protectorate of the British Empire. Mr. Fisher found that the country was quiet. Most of the archeological concessionaries had withdrawn from their excavations and in consequence laborers, many of whom had experience in excavating, were plentiful. The conditions were in all respects favorable for an expedition equipped to conduct excavations on the sites of one or more of the ancient Egyptian cities. The organization of the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Expedition was therefore completed under the patronage’ of the President of the Museum to carry on systematic excavations, subject to arrangement with the Egyptian Government.

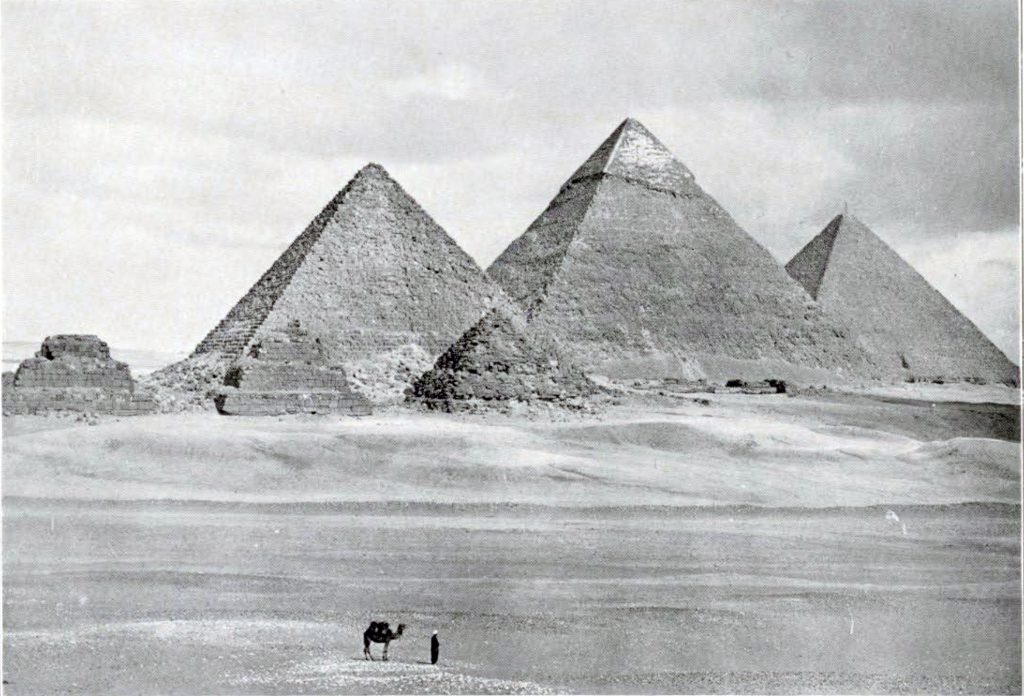

The first step to be taken was to secure through the Department of Antiquities of the Egyptian Government a site that would yield the results which the Museum was most desirous of obtaining. Mr. Fisher spent a month in preliminary examination of various sites in the Delta and in lower Egypt. For various reasons the choice of sites fell upon the following three. Tanis in the western Delta, a city dating from the sixth dynasty to the Roman Period; the pyramid fields at Gizeh, containing the great royal cemeteries of the fourth and fifth dynasties; and ancient Memphis, situated on the west bank of the Nile and dating from the earliest prehistoric times to the Arab invasion.

Tanis had, a year before Mr. Fisher’s arrival in Egypt, been divided between a French expedition and an Austrian expedition, but excavation on the site had not begun. Gizeh had several years previously been divided between an American expedition, a German expedition, an Italian expedition and an Austrian expedition. Professor Flinders-Petrie had begun excavations at Memphis in 1906 and continued these excavations during a period of three months each year until 1914. Some of the principal portions of the great site, however, still remain untouched. The cemeteries at the Pyramids had all been parceled out, but upon the proclamation of the British Protectorate the German concession and the Austrian concession were forfeited. Likewise the Austrian concession of the half of Tanis was forfeited. An application was accordingly made for the German and Austrian concessions at Gizeh which had been partly worked and the Austrian concession at Tanis which had not been worked at all. The government, however, at that time decided to reserve these forfeited concessions until the close of the war. By chance, one of the most important parts of the cemeteries at Gizeh had been assigned to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts which had conducted investigations there since 1903. Through the Director of these excavations an arrangement was made whereby a part of this site was transferred to Mr. Fisher to excavate on behalf of the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Expedition. The Museum has thus enjoyed this year an opportunity of participating in the excavation of the greatest Old Empire site in Egypt.

There remained Memphis. After an examination of this site Mr. Fisher applied for that untouched portion which was believed to contain at some depth the ruins of the Royal Palace of the New Empire. In due time this area was measured out and formally assigned by the Egyptian Government to the University Museum.

Mr. Fisher conducted excavations at Gizeh for a period of six weeks. Among the discoveries which he made was an offering table with two rows of inscription around its edge containing the names of Khufu and Khepra, the builders of the first and second pyramids, and that of Dedefra, a mysterious king of whom little is known and whose place in the fourth dynasty has not been determined. This is the fourth example of his cartouche that has been discovered. Another discovery of special interest made during the excavation of the Gizeh cemetery was an offering chamber built of mud brick with ribbed vault constructed of specially designed brick with interlocking joints. This is the first time that this type of construction has been found in Egypt or on any ancient site.

The tomb in which this vault was found is not of later date than the sixth dynasty.

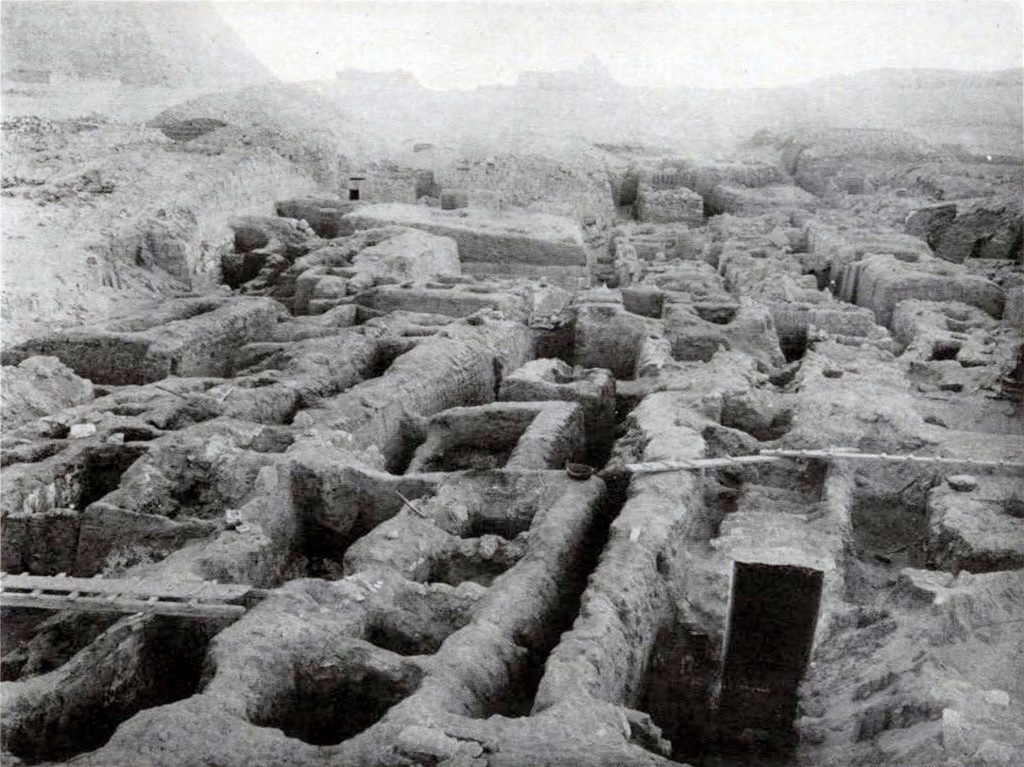

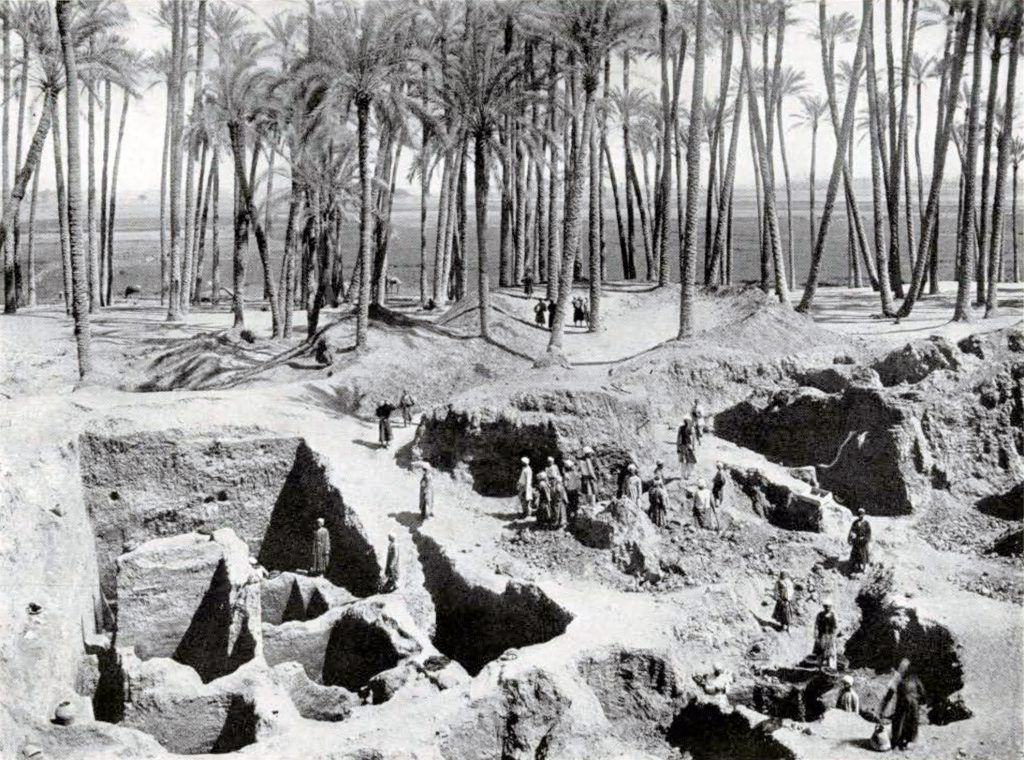

On March 11 Mr.Fisher moved his camp to the Memphis site and work was begun on the 13 of March with a large force of men. The surface of this area was covered with heavy mud brick walls of Roman or Ptolemaic origin. This represented the latest period of occupation. The first operation was to sink a trench down to water level where the sand and mud are saturated with water of the Nile. Below the upper level already described was found a second stratum of occupation which Mr. Fisher has not yet identified. Below this stratum were found traces of a great building which is presumably a part of the royal palace. As the seepage from the Nile at this lower level interfered with the excavations, a pump was installed to keep the diggings dry. In order to facilitate the removal of the dirt without encumbering the site, a section of railroad was laid down to carry to a distance the rubbish removed. In this way the debris of the excavations will not be allowed to encumber any part of the ruins and interfere with future excavations. The digging at Memphis has now proceeded for three months. The organization embraces a force of one hundred and eighty men and work has proceeded rapidly. On such a large site where so much debris has to be removed, the developments are slow and the laying bare of ancient buildings is a tedious and protracted operation. Nevertheless, the progress that has already been made indicates that the site was well selected. The objects that have been found during the three months’ digging have been numerous, although for the most part small. On April 10 Mr. Fisher wrote as follows.

“All the force is now employed on the area where the two exposed tops of columns attracted me some time ago. The plan of the whole is now developing and we have a great door leading to another room to the north. I am quite sure that we have the beginning of the palace here. The columns bear long inscriptions and the jambs of the doors have also inscriptions and reliefs of the king Merneptah making offerings to different deities. When first exposed all the inscribed parts are filled with mud and the surface of the stone itself is very wet and soft. Nothing can be done to it in the way of cleaning until this dries and then the earth peels off rather easily.”

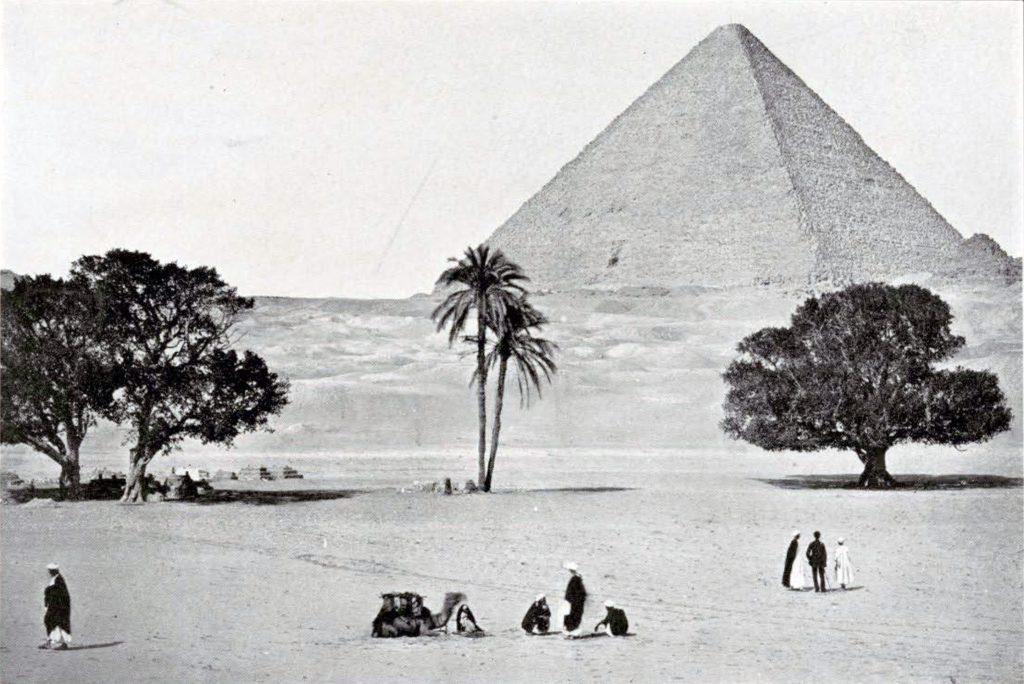

The Cemeteries at Gizeh

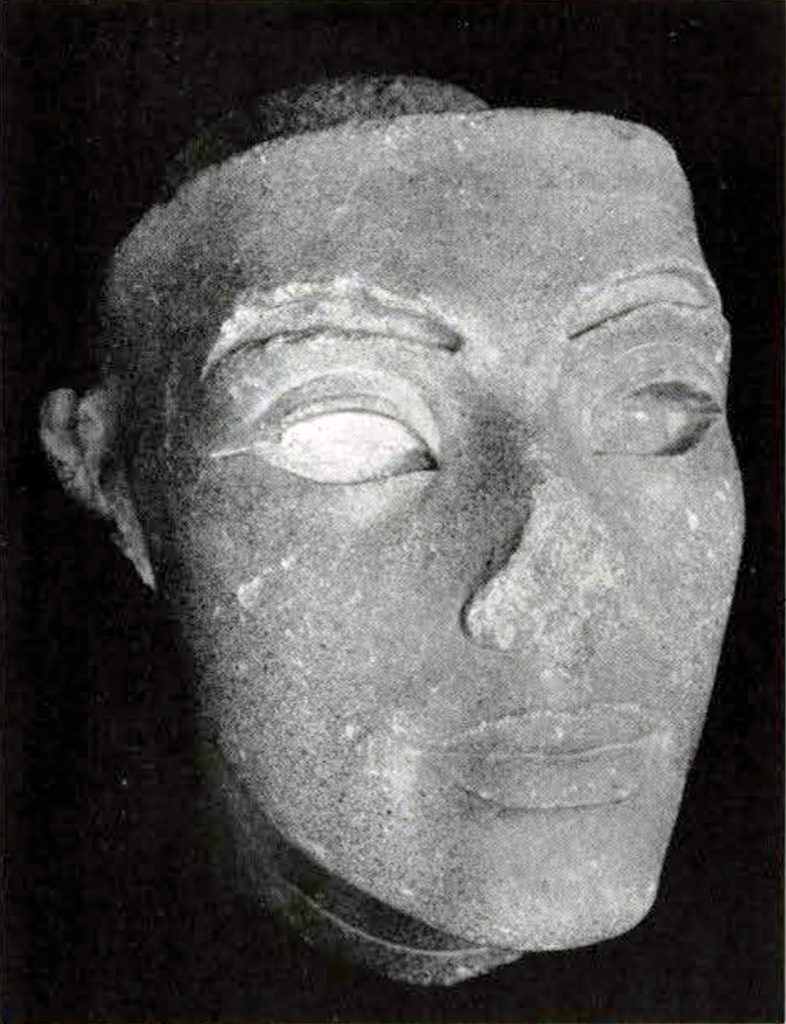

The very extensive cemeteries that surround the pyramids of Gizeh contain the tombs of royal personages and high officials of the fourth and fifth dynasties. This was the period during which Egyptian civilization made its greatest strides, when the foundations of the Empire were laid broad and firm, when hieroglyphic writing was perfected and when architecture, painting and sculpture reached their most refined development. The excavations of Dr. Reisner in particular, in these royal cemeteries, have revealed the high artistic achievement of the sculptors of the fourth dynasty, and the Boston Museum has accordingly been enriched by some of the finest examples of Egyptian sculpture which have ever been brought to light. The long and patient researches extending over a period of eleven years which Dr. Reisner has carried on have thus been richly rewarded.

Mr.Fisher was already familiar with the ground, having participated for several years as Dr. Reisner’s assistant in the excavations of the Boston Museum. During the present year the Boston Museum and the University Museum were the only institutions which conducted excavations at the Pyramids.

Memphis

Present day knowledge of the history of Memphis is derived from two sources, namely, from Herodotus and from hieroglyphic inscriptions that have been unearthed on the site of the city itself. Its history began with Menes, the first historical king of Egypt, who was the founder of Memphis or at least of its greatness as a capital. Accordingly, although it seems to have existed in prehistoric times, we may place the beginning of the history of Memphis at about 4000 B. C. Its history ended at the time of the Arab invasion when the Roman governor signed the capitulation in its palace. During its long history Memphis was the greatest capital of Egypt. It was the commercial center of the world. Through the highroad of the Nile its trade was carried to the shores of the Mediterranean. By caravan its commerce reached into Babylonia and even farther to the East. It is true that for a few centuries Thebes rivaled Memphis in importance and it is true also that after the conquest by Alexander the new city that he founded surpassed it in importance, but, as Professor Flinders-Petrie observes, “These cities are only episodes in the six thousand years of national life.”

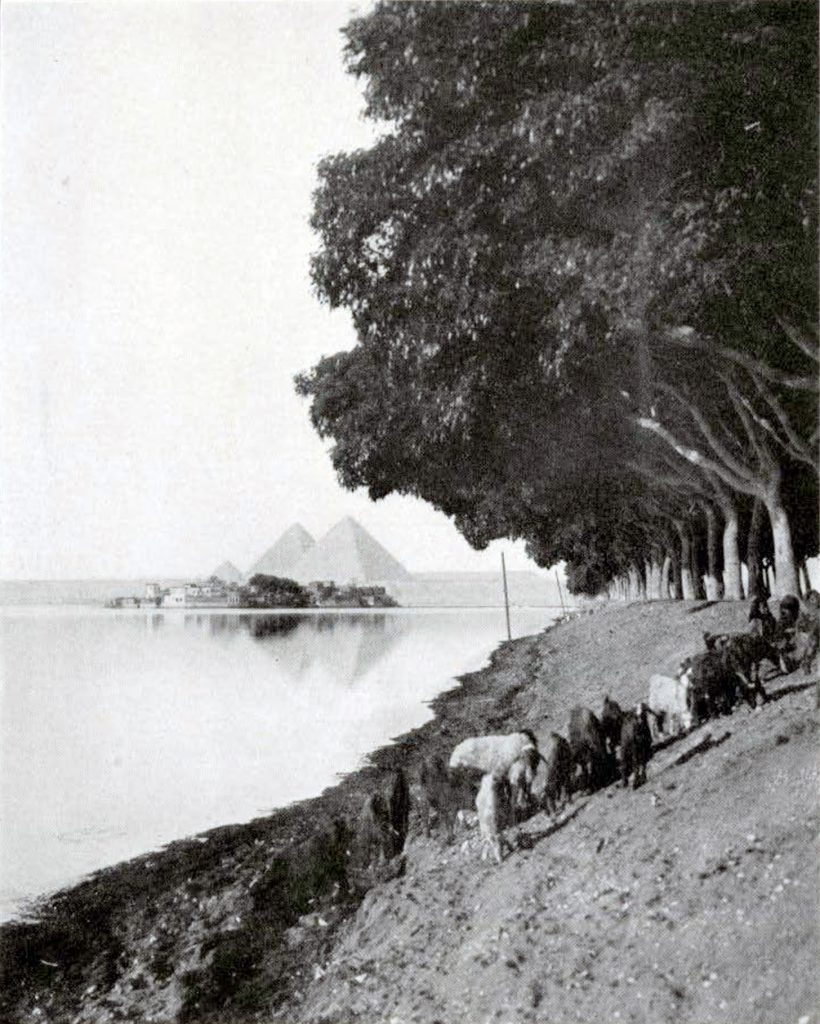

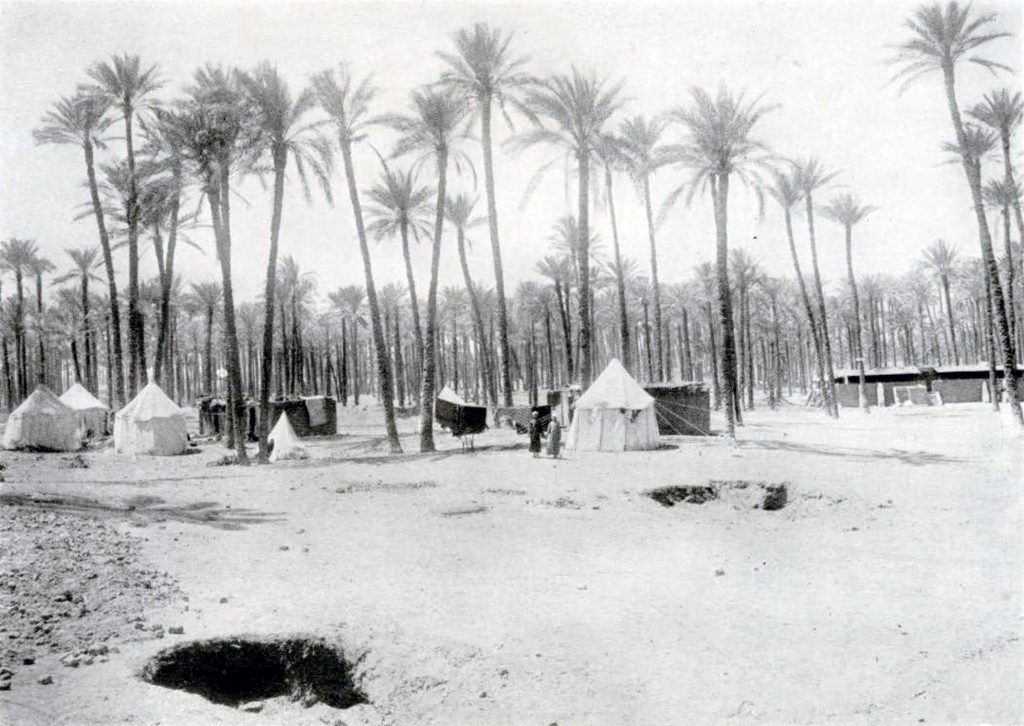

Memphis was situated on the west bank of the Nile about fourteen miles south of Cairo. According to the modern interpretation of the ancient authorities it stretched for a distance of eight miles along the bank and spread about four miles towards the desert. It contained the temples of nineteen gods, including that of the bull Apis. The greatest of the temples was that of Ptah described in detail by Herodotus. Today the site of Memphis is marked by a grove of palm trees, cultivated fields, heaps of rubbish and the modern town of Bedreshen. The sand from the desert, mixed with mud from the Nile, has accumulated to a great depth, leaving whatever remains of the ancient city far beneath the surface.

Since the time of the Moslem conquest, Memphis has been used as a quarry for building stone; its proximity to Cairo has exposed it especially to depredations of this kind. Much of that modern city has been built of material transported from Memphis.

Professor Flinders-Petrie began excavations at Memphis in 1908. These excavations were continued for several years, hut almost the entire site still remains to be excavated. The Museum, which had already participated in Professor Petrie’s excavations, has long had an interest in Memphis. The great granite sphinx which stands in the courtyard of the Museum formerly stood in the temple of Ptah at Memphis, where it was unearthed by Professor Petrie in 1912. Professor Petrie’s work was brought to a close at the time of the outbreak of the European war and since that time, the University Museum, through the Eckley B. Coxe, Jr. Expedition, has taken up the arduous task of excavating in a systematic way the site of the greatest capital of ancient Egypt.

Image Number: 36670

Image Number: 36668

Museum Object Number: E12326