The Conebo is one of several related tribes occupying the territory along the Alto-Ucayali River speaking dialects of the Pano language. Their cultures, while not identical, are very similar. One tribe may excel in the manufacture of one thing and supply its neighbors with that particular article. For example, the Piros make the best canoes and are the best canoemen; the Cashibos make the best bows and arrows; the Amahuacas raise the best dogs and trade them to their neighbors. The Conebos and Shipibos are the best pottery makers in the whole Amazon valley and furnish supplies to all their neighbors. The Conebo is the larger of the two tribes, makes more pottery and hence gives its name to all the Ucayali pottery, which makes it very difficult to distinguish the types. The decoration is practically identical, the method of manufacture is the same, the materials are similar, but the Conebos are the better mechanics and the better artists. Hence, one may be practically certain that all the most careful decorations are made by the Conebos, while any common piece may have been made by either tribe.

Image Number: 36769

Image Number: 17875

The women are the pottery makers and gather all the materials, while the men do most of the trading. A Shipibo trader, realizing the advantage, may marry a Conebo potter and thus complicate matters for the student.

The materials are all obtained locally. The white clay is collected from the river banks at low water and the pottery, on this account, is made during the dry season. The ash of the Ohé tree, or some other soft wood tree giving a very fine white ash, is mixed with the clay in an old pot where it can be kept clean. When the clay mixed with water has reached the desired consistency, a small lump is taken between the hands and rolled into a long fillet, the size depending upon the thickness of the pot. Then this is placed around on the edge of the pot being constructed, squeezed into place by the fingers, and rubbed smooth by holding a stone on the inside and rubbing with a shell on the outside. Thus the worker goes round and round the pot until it is completed.

When the pot is finished it is allowed to stand in the shade until it has hardened. If it is a cooking pot it is fired at once; if it is to be painted, a thin white slip made of very fine white clay is first applied and when dry the decoration is laid on with a strip of bamboo.

The rough pots are placed in a slow open fire and thoroughly burned. The fine ones are treated very differently. A large pot with a hole in the bottom is placed on three stones or more often three piles of inverted pots. The pots to be burned are inverted inside the large pot. The first one is placed over the hole and ashes poured around and over it, others are inverted over this until the pot is full or all are used. Then a slow fire is kept burning under the large pot until all are well cooked, when they are taken out one at a time and while still hot, melted copal is poured over them. This accounts for the glazed appearance characteristic of this pottery.

The various designs used in the decoration must have had some symbolic significance in the beginning, but at present no one seems to know the symbolism. They say they have always used these forms but don’t know why.

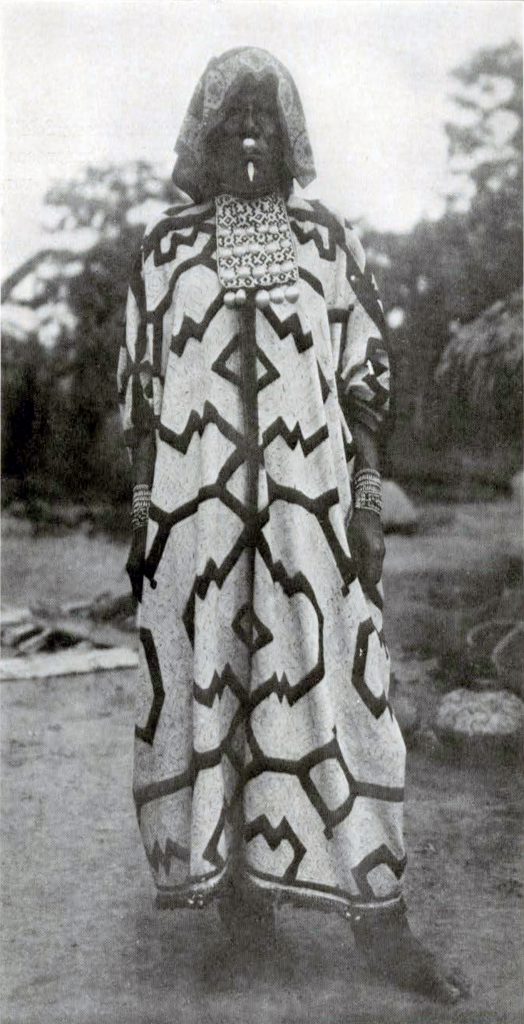

The rough pottery is used for the ordinary cooking purposes; the small bowls for dipping food and drink from the larger pots; the larger bowls for passing drink to guests; the larger jars with short necks for carrying and storing water; while the largest of all are made primarily to hold the intoxicating drink used at the puberty ceremony for girls.

At the time of this ceremony a great fiesta is held when all drink freely of “chichi,” the native intoxicating liquor made from fermented juca (sweet casava) and corn. The mother of the girl makes one or more of these very large pots to hold the supply of liquor for this occasion. After the ceremony they may be used for any kind of storage purposes. The largest one in the collection sent to the Museum, which is the largest I ever saw, was filled with beans. Another of these jars was filled with unfermented drink.

Image Number: 17914

To make the “chichi” the younger women chew the root of the juca until saliva is thoroughly mixed with it and then spit it into a large wooden trough, made from the hollowed trunk of a tree. The trough is then placed in the sun for two or three days while the mass ferments. Ripe corn is then finely ground and added with water. Fermentation continues for two days more, during which the liquor is constantly stirred. The girls strain it through closely woven baskets of palm into the large pots, where it is allowed to ripen for three or four days. All the time the girls are working with it they expectorate into it, even after it has been strained into the large pot.

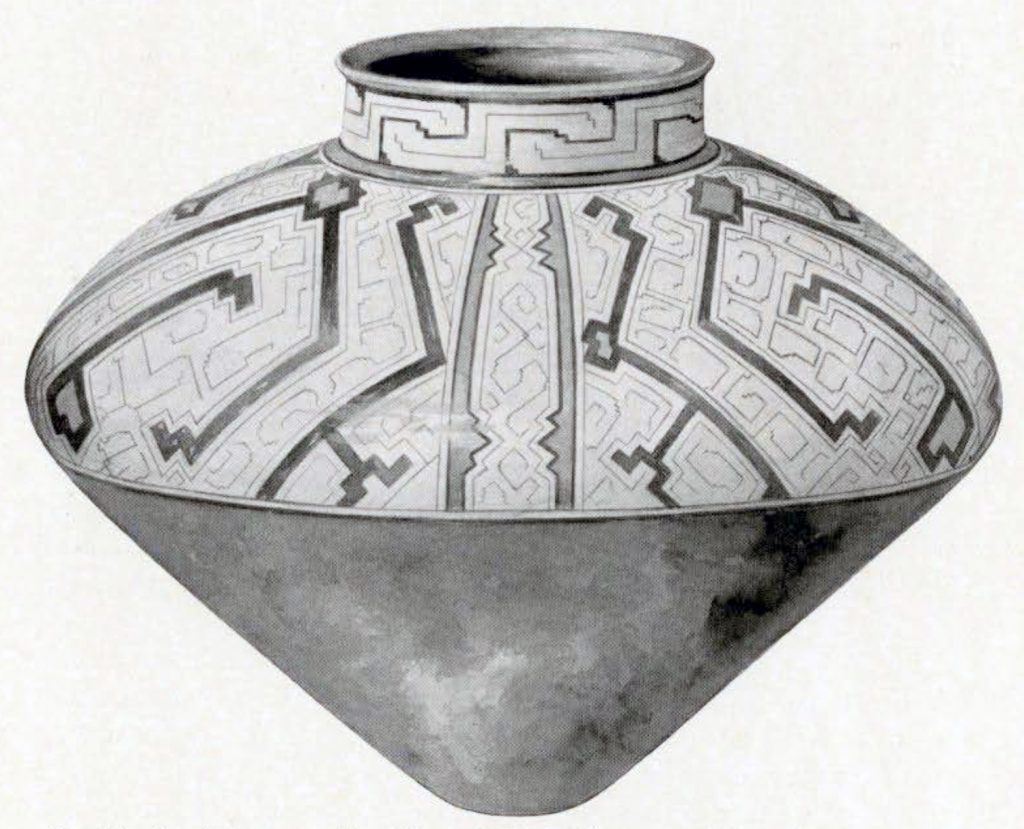

The account of Conebo pottery given -above is taken from Dr. Farabee’s notes. The collection which he sent to the Museum consists of over two hundred pieces varying in size from that of a teacup to great jars four feet in diameter and three feet high. The material is a fine clay containing a small amount of sand. All of the vessels are built without the use of the wheel. They are usually quite symmetrical in form and the walls are remarkably thin. The ware is uniformly fine in texture, is well burnt and gives forth a clear metallic note when struck. The decoration in the great majority of the specimens is uniformly of a highly conventionalized character corresponding in style to what is usually described as geometrical.

In a few instances animal and vegetable figures appear. The designs are applied freehand in broad bands or in fine lines upon a white slip, and the colors are black, red and brown.

All of the decorated surfaces are covered with a coat of transparent copal which gives the pottery the appearance of being glazed. The inside of each vessel is usually covered with a thicker coat of copal.