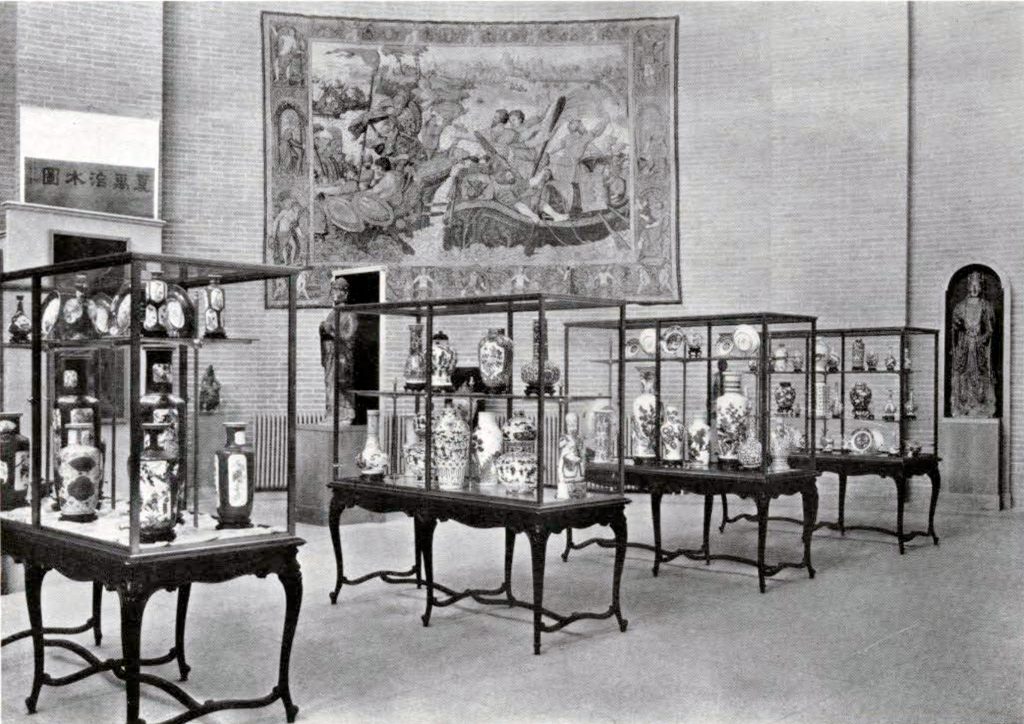

The three months beginning November 1, 1915,were occupied by the installation of the Exhibition of Oriental Art that had been planned in connection with the opening of the new exhibition hall on the main floor of the Museum. The installation was completed early in February and The Charles Custis Harrison Hall with the exhibition of Oriental Art was opened with a reception given by the President and Board of Managers on the evening of February the 12th. On the 13th the exhibition was opened to the public and since that time has continued to attract a large number of visitors.

During a period of about two years the Museum has been gradually acquiring examples of the antique art objects of China and other Eastern countries. In addition to these acquisitions there are shown in the present exhibition a number of examples of the very highest merit which the owners have generously lent for the purpose. The principal part of the exhibition is Chinese; the other countries included, Persia and Tibet, are each represented by collections which, while numerically much smaller than the Chinese, are of the very highest importance and would in themselves comprise an exhibition of very unusual interest, showing examples of the best in each period of Persian Art and in the art of Tibet.

Chinese Sculpture

Image Number: 173852

In assembling the collections to form the exhibition, first attention was naturally given to the Fine Arts as represented by sculpture and painting. The collections representing the minor arts, such as the decorated bronze vessels, the porcelains, the potteries and carved jade, are of necessity more prominent numerically, but the keynote of the exhibition is struck by the Chinese sculpture. Though small in number compared to other groups of objects in the exhibition, these powerful creations of early Chinese artists exercise a dominating influence and sustain the supreme position of sculpture the world over as a means of giving form to the highest ideals.

The sculptures in the exhibition begin with the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-25 A.D.), extend through the Wei Dynasty (386-549 A.D.), the T’ang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.), and come down to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1643 A.D.). This extension covers the rise, culmination and decline of sculpture in China, which had its golden age in the period of the Tangs. The range of this sculpture extends all the way from the genre type of clay statuettes, reminding one of the Tanagra figurines, and taken from the tombs of the Tang period, to heroic figures in stone representing Buddhist divinities. In using clay as a vehicle and shaping this soft material into forms of lifelike eloquence, combining an easy grace of line with great power of expression, the knowledge and ability shown are at times startling. Technical skill, combined with imaginative genius, is seen in many fine examples made by masters of the T’ang period. It is seen in the figure of a horse and in the larger than life seated statue of a disciple of Buddha, both in the same medium, clay. The last named superb piece of plastic art shows in a remarkable way how the lump of clay under the master’s touch becomes instinct with life and quick with spiritual and intellectual fire.

Other sculptors of the same era, using hard stone as their medium, have handed down to posterity works that claim our greatest admiration and respect. Among the considerable number of stone sculptures in the Museum collection, which date from the T’ang Dynasty, all of them on a very high plane of artistic and historic interest, there are at least six statues that are very great masterpieces. Four of these are larger than life and two are under life size. All represent Buddhist conceptions of Divinity. They impress one at once with their latent qualities of immobile power and of energy in repose, qualities that seem to belong especially in the province of sculpture. These true impressions lose nothing on more intimate acquaintance. On the contrary they become associated with other qualities which combine to produce an effect of great dignity and power on the one hand and great refinement and charm on the other.

Image Number: 174389

The Chinese sculptor never lost sight of the advantages to him of the properties of solidity and mass that are inherent in stone. His art availed itself of these characteristic properties at the same time that it drew upon its own infinite resources of sweetness and strength. His favorite subject was the human figure; but ignoring the obvious and irrelevant, he saw only the essential and the noble. He was not trying to shape man, but God, and his sturdy figures in their majestic grace are in reality more divine than human.

An examination of the entire body of early Chinese sculpture in the University Museum brings into prominence one characteristic, already implied, of the Chinese sculptor and his work that is not unknown to students of the works of other ancient peoples among whom the plastic art stood at a high level. Whether he moulds his figure in clay or works it out of stone, whether his subject be man or God or beast, the essential condition of his art is a static posture. If the idea of action is to be conveyed, it is implied but never directly rendered. This refers only to sculpture in the round and not to relief, which is a different thing.

The two clay horses in the Museum collection, one glazed and the other unglazed, illustrate this recognition on the part of the sculptor of certain conventions, limitations of method or canons of taste and form that to him governed the practice of his art. The horse stands with his four feet planted squarely and firmly under him. He stands stock still, a position in which no action whatever is represented, yet action is implicit in every line of his massive body and of his unbent legs. Saddled and bridled, his part is that of discipline and self-control. It is also that of a very real and very sanguine horse, that “paweth the valley and rejoiceth in his strength, that saith among the trumpets, Ha! Ha! and smelleth the battle afar off.”

Image Number: 217424

Chinese Painting

It is far otherwise with the art of painting, which in the T’ang Dynasty had already advanced into its own fields and mastered them completely. In these free fields the Chinese painter is the happiest of his kind. His subjects are varied. He may paint emperors in their robes of state, or priests, or beggars, or portraits of grave seniors or children at play, or demons or domestic scenes or scenes at court and these are rendered with great subtlety of line and refinement of feeling and yet with directness and simplicity and with a self-confidence that is often astonishing.

It is as a landscape painter, however, that this Chinese artist excels. In the Museum collection are forty-seven paintings and twenty-five of these are landscapes. These paintings range in date from the T’ang to the Ming and include many landscapes of the classic Sung. They all convey a lively idea of the landscape painter’s work. He gets very close to Nature and maintains towards her varying moods the intimate and sympathetic relationship of a familiar spirit. The Chinese painter worked upon silk and his medium was black ink or inks of various colors. With such materials as these and with the intricate resources of light and shade, every variety of motion came as natural modes of expression and could be rendered with the utmost felicity. Still this artist is never carried away by his license. He avoids a riot of action as he avoids a riot of color. His paintings are always restrained and temperate. It is thus that he shows us the storm, the mist on the hills, the wind in the trees, the flight of birds across the fields, the hunter returning from the chase riding his horse, the peasant at his plow, the conflicting passions of men and the rapacity of beasts. In dealing with these things that make up the objective world, and in showing forth the relation between fidelity of line and the poetry of motion and especially in translating the epic moods of Nature, Chinese painting has never been surpassed.

It has already been shown that Chinese sculpture, dealing with subjective things, under the influence of Buddhist teaching, displays a peculiar power in its revelation of the ideal of an orderly Universe and Mind in repose. It is true throughout the whole body of Chinese Art that the painter and the sculptor has each his own province and neither encroaches on the other. The painter represents the horse carrying his master and there is grace and swiftness in the action of his bent limbs, but it is the sculptor that has “given the horse strength and clothed his neck with thunder.”

Bronze Vessels, Pottery, Procelains and Jades.

In this exhibition may be seen an admirable series also of early Chinese bronzes (sacrificial vessels) made principally during the Chou Dynasty (1122-255 B.C.), and during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-25 A.D.). It also contains examples made during the Sung, Yuan and Ming Dynasties. These objects of ceremonial or domestic use show the work of the craftsman as well as the work of the artist. Their form and decoration are part of an elaborate and formalized symbolism which preserves during the later periods, traditions of the ancient times. These bronzes represent an early phase of art and belong to the general background of artistic development that was not informed by the Buddhist tradition, which, when it came to China from India during the early centuries of our era, found the artistic sense of the Chinese bound up in conventionalized forms. To this period belong the bronze vessels; they show the rude strength of a more barbaric art, but not the scope or the imagination of the period that followed.

Museum Object Number: C100A

Image Number: 10702

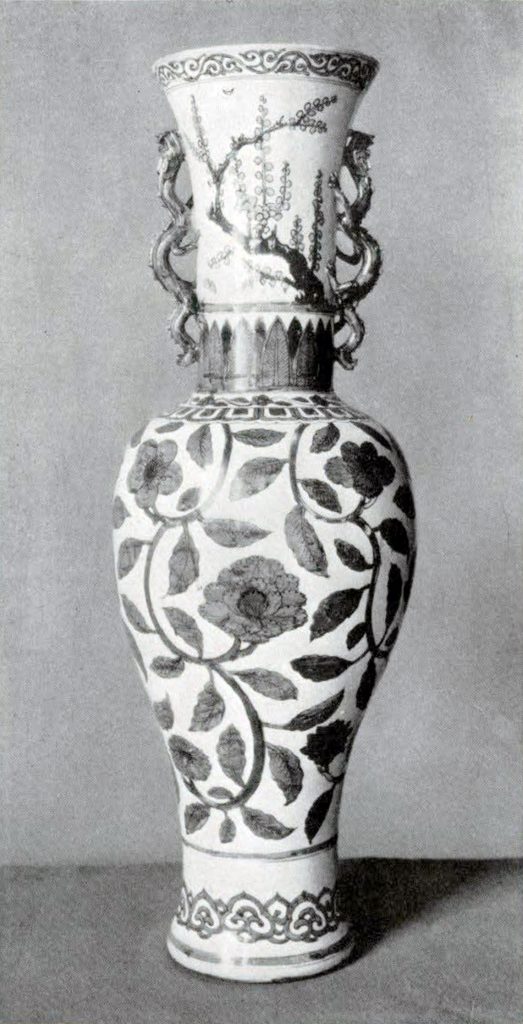

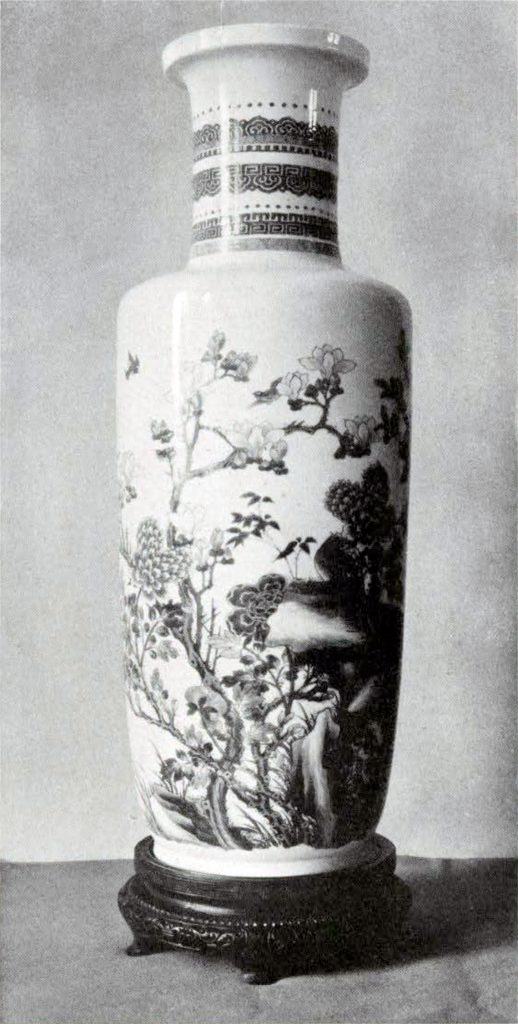

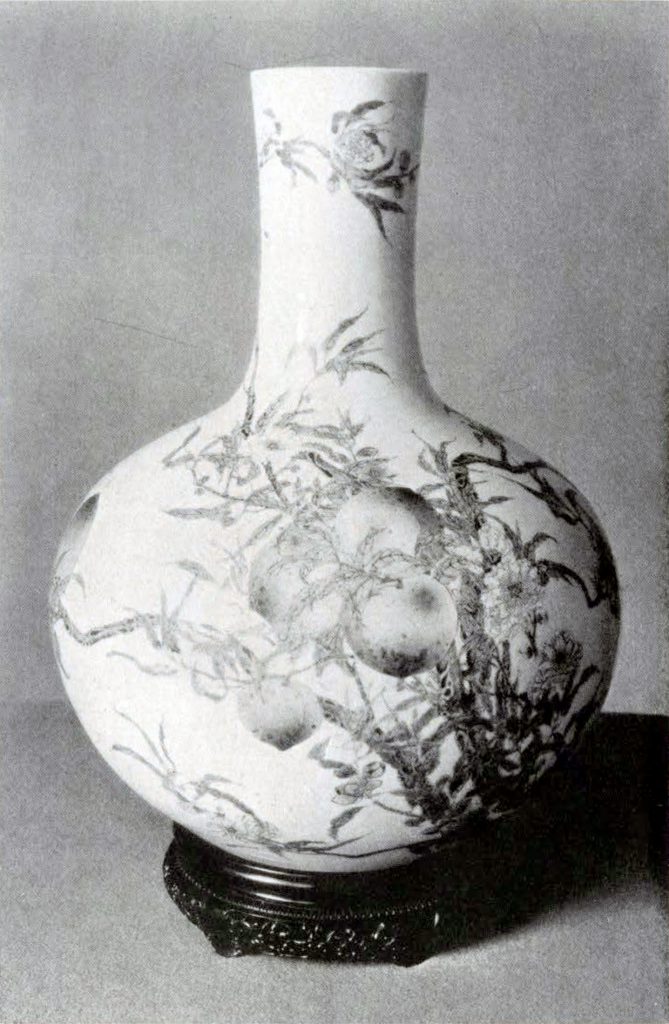

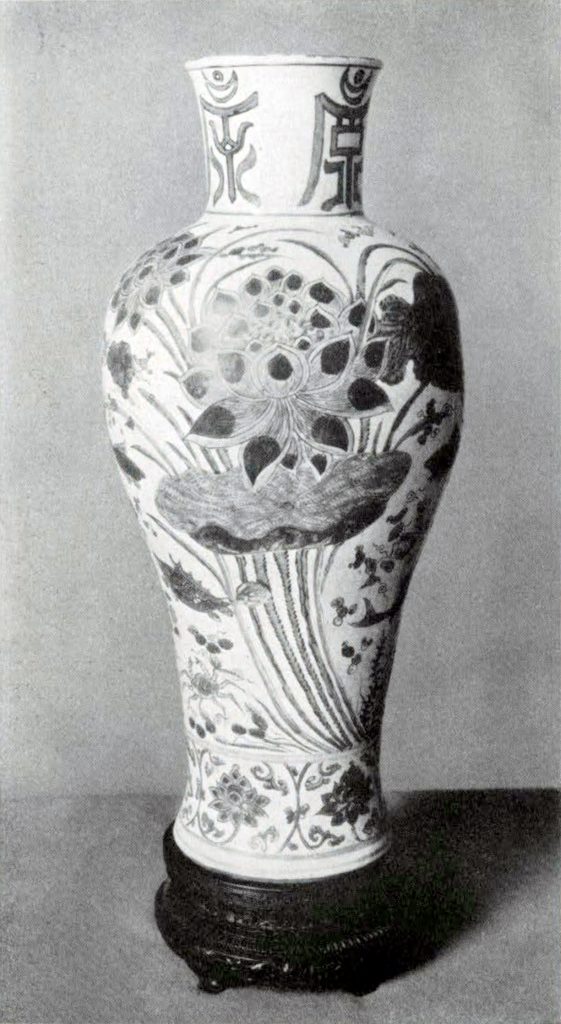

Pottery is included in the exhibition to show the ceramic products of the earlier periods. The potter was at work in the very earliest times, even before the bronze worker; his wares were first crude and plain, but there came a time when the potter began to reproduce the forms and decorations of his fellow craftsman and we find the pottery of the Han Dynasty imitating the shapes of the bronze vessels of a still earlier period. About the same time a glaze was discovered and the ceramic products underwent progressive refinement until pottery merged with the porcelain of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Although in the course of this development, the one merges into the other, anyone who observes the potteries on the one hand and the porcelains on the other, will be struck with the wide distance that is between them. Beautiful and exquisite as they are in form and color, the porcelains are wanting in some of the qualities that appeal so powerfully in the pottery. The porcelain vases, made purely for ornament, have a tendency toward formality. Admirable though they are, they are apt to leave one cold, because they lack the intimate human touch that is present in the pottery. The vessels of this latter kind were made for use and their form is determined by the service to which they were put. They show how the potter was able to shape vessels of domestic use so as to satisfy his sense of beauty. The artist craftsman of the porcelains strove only to gratify sense of form and color through his appeal to the eye.

Besides the bronzes, the pottery and the porcelain, other minor arts are well represented in this exhibition of Oriental Art. Cloisonné enamel, a product of the Ming Dynasty, occupies one case, and carved jade occupies another. In each case the examples shown exhibit the best qualities of these two products of the Chinese arts and crafts in the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Image Number: 1667

Image Number: 1642

Persian Art

The three cases of Persian pottery make one of the most interesting features of the exhibition. The Asia Minor pottery and Rhodian ware that represent a later stage in the history of Persian ceramics have their own interest, historical and artistic. The earlier Persian potteries in the collection were made at Rhages in the eighth century and show that they owe their form and color to the Chinese potteries of that early period. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Persian pottery had entered paths of its own and the Rhages ware of that period is exquisite in form, color and decorative motives. From this time on to the sixteenth century the Persian wares multiply in variety, culminating in the very beautiful lustered plates and bowls made in the sixteenth century and now extremely rare.

Persian painting is represented by a case of miniatures and several illuminated manuscripts of the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Persian textiles are represented by a number of very exquisite pieces which show a wide variety of design and which were made on the looms of Persia and Asia Minor during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Image Number: 4260

Image Number: 10709

Image Number: 1636

Image Number: 1694