In planning the University Museum’s Eastern Asiatic Expedition, or, more properly speaking, reconnaissance, it was considered desirable to study the possibilities for archæological research and collecting in several distinct and widely sundered areas. Among these was, for one, the region anciently inhabited by the Yamato race, the founders of the Japanese Empire; and, in connection with it, those portions of eastern and northern Japan formerly occupied by the Stone Age predecessors of the Japanese and only subdued after centuries of the most savage border warfare. Korea, for lack of time, it was necessary to treat as a unit, although really very great differences have existed, particularly in early times, between the north and the south of that peninsula. In China the objectives chosen were two: the seat of the oldest Chinese civilization of primitive days, in the upper Yellow River valley; and those regions lying to the west and southwest, bordering upon Tibet and Further India, which were annexed to the Chinese Empire in relatively late times and are still imperfectly assimilated.

The few weeks immediately following my arrival in Japan, in February of 1915, I devoted to a study of the central provinces, with their historic sites, their public museums, and their private collections. Throughout this work I met with the utmost courtesy and helpfulness from all with whom I came in contact. I was fortunate enough to be the bearer of letters of introduction from H. E. Viscount Chinda, the Japanese ambassador at Washington, to a number of gentlemen high in official and educational circles in Tokyo, and from all of these I received invaluable help.

The region about Nara and Kyoto, the two ancient capitals (the former from A.D. 709 to 784, the latter from 794 to 1868) is particularly rich in remains of the past of every sort and period. The countryside is studded with graves dating from the so-called dolmen or protohistoric period, which terminated roughly with the seventh Christian century. In connection with these many interesting discoveries have been made, partly as the result of accident and partly through scientific investigations conducted by properly equipped archaeologists. During that early period it was customary to bury the more important dead in baked clay sarcophagi painted with vermilion; one of these, through the good offices of a Japanese friend, I was able to secure for the University Museum.

From Nara I proceeded to the province of Ise, not far distant, where it was my privilege to visit the sacred shrines, the holiest in the Empire, and to inspect the Imperial Museum at Yamada, close by. This museum, while smaller than those at Tokyo and Kyoto, is highly interesting for the light which it throws on some of the earlier phases of Japanese life. Particularly good are the life-size groups illustrating the costumes worn from the earliest known times downward.

Prior to the introduction of Buddhism from China the capital of Japan had not been fixed, but had been moved from place to place. This nearly always took place at the death of a sovereign, when his habitation was looked upon as having in consequence become unclean. The growing complexity in social and political organization, however, and also the improvements in temple and palace architecture learned from the Chinese and Korean Buddhist missionaries, made it more and more inconvenient to move the capital about from place to place. At length it became definitely fixed, first at Nara and then at Kyoto, as already stated, and at these centers Chinese influences held almost undisputed sway for some centuries.

Image Number: 4368

Image Number: 4357

Image Number: 4401

The one factor which more than anything else preserved Japan from developing along the lines of Korea, and becoming merely a second or third rate imitation of the Chinese Empire on a small scale, was the development of a military class and a military tradition. This was the result of the long and bitter struggle with the aborigines of the eastern border. These people, when first known, seem to have been in a high stage of the Neolithic or later Stone Age; soon, however, they secured weapons and armor of metal, partly from the dead bodies of their Japanese foes, left on the battlefield, and partly through an illicit trade as highly reprobated as was that in firearms carried on by unscrupulous traders with the Indians of our own frontier days. Numerous, brave, and often ably led, these barbarians, whose degenerate descendants are now known as the “hairy Ainu” of the island of Yezo, held their own in the northern part of the main island of Japan for many centuries.

Image Number: 4363

While in Kyoto I was able to purchase for the University Museum a set of MSS. volumes, profusely illustrated with watercolor sketches, and giving an account of a visit by a Japanese official, late in the eighteenth century, to the Yezo Ainu. This account, in journal form and written by a man who was evidently a close, conscientious, and sympathetic observer, as well as an artist of no mean ability, at a time when the Ainu had been far less modified than is the case today by contact with outside cultures, seemed likely to prove of value as throwing new light upon the past of an interesting but little known and now nearly extinct race.

In this connection I made a visit, about the middle of May, to northern Japan, with the twofold object of seeing what I could of the surviving aborigines, and of studying the remaining traces of their former occupancy. That most important epoch within which the Japanese and Ainu races were in such long and generally hostile contact has been singularly slighted by foreign writers. This is the more curious because it was within this period, and on account of that contact, that the Japanese racial character took on all the dominant traits which distinguish it today. It is very much as though writers upon American history should confine themselves to the purely local development of the Atlantic seaboard and its relations with the European countries from which our civilization is derived, and ignore or at best barely mention our Indian wars and the gradual occupation of the country between the Alleghanies and the Pacific.

My first objective was the site of the ancient Taga fort, erected as an outpost against the Ainu in A.D. 724, near where the present city of Sendai stands. The fort stood for half a century, and then was stormed by the northern barbarians, who massacred the entire garrison and pushed their raiding parties two hundred miles to the southward, into the region about the present city of Tokyo. At that period the Japanese castle had not developed into the many storied structure with elaborate moats and snow white walls and roofs of tile that dotted the country in later days. It was merely an earthwork, usually perched upon a hill, and consisting perhaps of a number of concentric embankments surmounted by palisades, with a wooden blockhouse in the center as a last refuge for the garrison in case the outer works were carried. The type was one familiar enough to our forefathers in the Transalleghany country.

I found the ancient fort situated upon the crest of an isolated hill, surrounded on practically all sides by deep ravines, pools of water, and low-lying marshy ground, and commanding what was, in 724 as in 1915, the main road to the north. Several more or less concentric lines of earthworks were still discernible, overgrown with trees and bamboo thickets, and part of the site is occupied by a tiny farming hamlet with its surrounding fields. Upon the truncated summit of the hill, embedded in the soil, are to be seen rows of huge flat stones which served as bases for the great wooden columns forming the uprights of the old keep or donjon. The soil of the entire site is constantly yielding fragments of pottery, roofing tiles, and other articles of ancient type, washed out by rains or turned up by the hoe of the peasant, and would undoubtedly abundantly repay excavation and detailed study. Certain fragments of the pottery seemed to me to resemble those from neolithic sites, and in fact the position is just such a one as would have been occupied by a community of the aborigines before the Japanese invaded the region.

From the Taga fort I went, via Aomori and Hakodate, to Sapporo, the capital of the island of Yezo, and there, thanks to a letter of introduction to the Governor General which I bore, I was accorded every facility for pursuing my investigations. After conversations with the Rev. John Batchelor and others familiar with the existing settlements of the Ainu, I decided upon visiting Piratori and Niptani, two villages in the southern part of the island. Upon my arrival at the first named place, late at night, after a long and cold ride in a rickety old basha or stage, I found to my intense delight that the place contained a snug and spotlessly clean little Japanese inn, and that my visions of having to sleep in some Ainu outhouse were quite groundless. Presently the Japanese mayor of the town called and stated that he had received telegraphic instructions from Sapporo that I was on the way, and was to be shown every assistance. This wholly unasked and unlooked-for act of thoughtfulness on the part of the government was quite in keeping with the treatment which I received throughout the Japanese Empire.

The mayor told me that he believed the Ainu I might meet would feel freer and less constrained about answering any questions might put to them regarding their present condition if I were Provided with an interpreter of their own race, and that he had accordingly instructed a young Ainu, educated at Tokyo and now employed in his office, to accompany me the following day. Early next morning the young man appeared, and took me to visit several Ainu families in the community. I also had the pleasure of calling upon Miss Bryant, a most devoted English missionary who has spent eighteen years in this region, and who gave me a number of valuable suggestions regarding the best use to be made of my time.

One of the points of interest in the vicinity of Piratori was the so-called Shrine of Yoshitsune, a plain wooden building on the hill back of the village, closely resembling an ordinary Japanese shrine, but with a roof of shingle instead of thatch. It is dedicated to the famous Japanese hero of the twelfth century, who aided his elder brother Yoritomo to establish himself as shogun, or de facto ruler of Japan. Later, having the misfortune to incur his brother’s causeless jealousy, he was forced to flee to the wilds of the northern part of the main island, where he had spent his youth, and here he is generally supposed to have been slain by his brother’s emissaries. How and where he became an object of adoration among the Ainu is unexplained. Certainly no cult of Yoshitsune exists generally among the Ainu, and so far as I am aware there is no other shrine in Ainuland to the memory of the hero. Even here at Piratori there is apparently no active worship conducted at the shrine, which would appear to be nothing more than a memorial. On the other hand, that Yoshitsune has been an object of reverence among the Ainu for some time is suggested by a passage in eighteenth century Japanese literature which mentions songs in his honor sung by natives of Yezo, and “closely resembling the ritual of the Shinto worship.” Curiously enough, one legend takes Yoshitsune not merely to the island of Yezo, but into the heart of Asia, where he reappears as the world-conquering Genghis Khan, the leader of the Mongols.

Leaving the settlement of Piratori I got myself put across the Sam River in a narrow and cranky dugout canoe poled by an ancient Ainu of kindly mien, but most unbelievably filthy in person and clothing. About an hour’s walk in the rain brought me to the next village, Niptani, which was much more typically Ainu in all respects. Here, in spite of wind and sleet, I managed to get some photographs illustrative of Ainu architecture, and had an interesting chat with the village headman, a fine looking man with a heavy iron-gray beard, who had traveled as far as London, he proudly told me. I won his heart by taking a picture of his favorite riding horse, a great black stallion of American stock from the government breeding farms near Sapporo. The Ainu have been horsemen for ages. Whether they originally secured their horses by raids upon the border settlements of their Japanese enemies, or whether they brought them direct from the Asiatic continent, is doubtful; but the fact remains that at a very early period they had large herds of horses, which they traded to the Japanese for metal arms and armor.

Image Number: 4302

It is curious, and perhaps significant, that Ainu storehouses elevated above the ground on posts, such as the Ainu still use, were known to the ancient Japanese, and in fact still survive as sacred treasuries in temple enclosures. The same type of storehouse is known in the Loochoo Islands, between Japan and Formosa, where the people speak a language allied to the primitive Japanese tongue and are in part at least an early offshoot of the same race. These storehouses form a well-marked feature of the Ainu villages, as do the great piles of wood split and piled up near the houses against the bitterly cold northern winter.

I was greatly pleased to see at Niptani the school conducted by the Japanese authorities for the Ainu children. It seemed well equipped with all appliances needful for both work and play, and the school children appeared both bright and happy. I was told, too, that Ainu soldiers had taken part in the Russo-Japanese War, and had acquitted themselves loyally and bravely.

Upon my return to central Japan I was able to secure for the Museum a makimono or picture roll painted in the early seventeenth century, depicting episodes in the wars which took place in the wilds of northern Japan about the close of the eleventh century, when that distant and barbarous region was definitely brought to recognize the sway of the Emperor ruling in Kyoto. The Ainu tribes of the country had been overthrown and subjugated by bands of Japanese invaders two or three centuries earlier; but these conquerors, like the early Normans in Ireland, once they had made their conquest good, refused to submit themselves to the authority of the central home government. The makimono depicts the overthrow of one of these rebellious northern chiefs by Minamoto Yoshiiye, better known as Hachiman Taro, or “Firstborn of the God of War.” While the painting was executed long after the period when the events depicted took place, yet the artist appears to have avoided anachronisms very successfully; and in fact there is good reason to believe that it is a faithful copy of a much earlier painting.

Image Number: 4312

Early in June I went to Nikko to witness the celebration of the tercentenary of the death of Tokugawa Iyeyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was most instructive to examine the collections of the various temple treasuries, not ordinarily placed upon exhibition, as well as to watch the processions, with their troops of armored pikemen and archers and arquebusiers and horsemen, their standard bearers, and their attendants, all decked out in the actual armor, costumes, banners, and weapons of the day, three hundred years before, when the great shogun breathed his last. The one jarring note was afforded by a pikeman who trudged past the reviewing stand smoking a cigarette between the bars of his helmet.

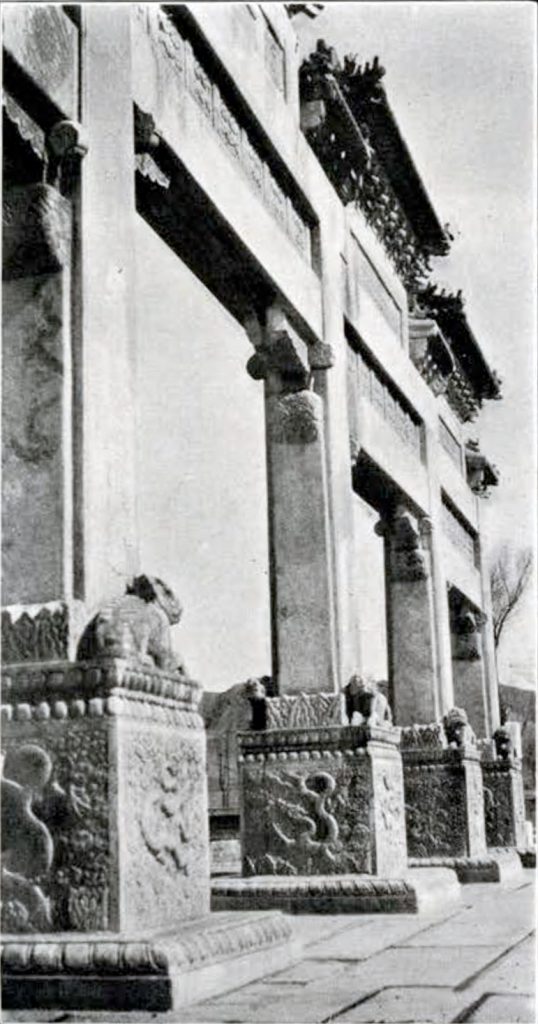

The latter part of July found me in Peking. As nearly all of the people whom I wished to see were away for the summer, I seized the opportunity to visit most of the local sites of interest, although the intense heat made sight-seeing the reverse of pleasant. I also managed to get in touch with a number of people who later placed me under deep obligation by their kindnesses.

By the early part of September I was back once more in Japan, for the purpose of inspecting the Imperial treasury of the Shosoin, at Nara, a privilege which I owed to the courtesy of the Imperial Household Department. This collection is very rarely shown. Indeed, Murray, in his “Handbook for Japan,” goes so far as to state that it “is now never shown,” while Terry says, in his “Japanese Empire,” “Unfortunately it is now closed to all except persons of the highest rank, and then only in October, when the treasury is opened for the purpose of airing the contents.” Consequently I was deeply gratified at this additional act of kindness on the part of the Japanese authorities in extending to me permission to inspect this ancient and unrivaled collection.

The contents of the treasury consist in large part of the palace furniture of the Emperor Shomu, who reigned during the eighth century, when the capital of Japan was at Nara. Upon his death these articles were presented by the Empress to the Todaiji temple there. They comprise a wide range of objects, many of Korean, Chinese, and even Persian or Roman (Syrian) origin, and include bows and arrows, swords, spears, javelins, an odd sort of halberd with a blade shaped like a lambent flame—a type peculiar to the period—mirrors, decorated boxes, collections of Buddhist sutras, masks used in sacred ceremonies, musical instruments, games, robes, shoes, banners, tapestries, jewelry, glassware, and many other articles. I found at the Shosoin the aged Dr. Matano, then President General of the Imperial Government Museums, but since, I believe, retired, whom I had known in Tokyo. With him was his first assistant, Dr. Tsuda, who spoke English fluently and who described to me most interestingly the various objects and the purposes for which they were meant.

Nowhere else in the world, of course, does such a collection exist. No collection of objects of the early T’ang and preceding dynasties of China is to be found in that country such as this at the ancient Japanese capital. Of early Korean art there is nothing in that peninsula to compare with the examples treasured for nearly twelve hundred years in this plain old log building in the quiet groves of Nara.

Late in September I again went to Korea, where, at Seoul, the capital, I attended the celebration and exhibition in commemoration of the fifth anniversary of the union of the two countries, and also of the completion of the first thousand miles of railroad. The Japanese officials were again most courteous, among other favors providing me with a pass over the entire Korean railway system in order to facilitate my researches. It is scarcely possible to overstate the benefits accruing to the Koreans as a result of the annexation of their country to the Japanese Empire. A little over three hundred years ago Korea was the battlefield over which fought the armies of Japan and China, and of course the country suffered, in much the same way as Germany during the Thirty Years’ War of the following century. Now, however, the Japanese are very much more than making up to the Korean people for any past injuries. For the first time the masses of the people have enjoyed the privileges of equitable taxation and justice in the courts. The man who by industry had accumulated a little property no longer goes in daily dread of being tortured to compel him to turn over the lion’s share to some idle and corrupt official. The money raised by taxation is spent for the development of the country and not for the enrichment of a worthless court which, through misgovernment, had brought the country to the lowest pitch of degradation. The position of the women has been much improved. Schools have been established. The hillsides have been reforested, sanitary precautions have been introduced, railroads and telegraphs extended throughout the country, agriculture improved, the mines and the fisheries developed—in short, the country has, in the almost incredibly short space of five years, been placed upon a modern footing, with every opportunity for the inhabitants to develop themselves and their national resources as freely as they please. To desire a restoration of the former conditions would seem inconceivable as the act of a sane and disinterested mind.

Upon leaving Seoul I was presented by the Government General with two magnificent volumes of plates illustrative of the work that has been done in the study of the archæology of the country, and especially of the ancient graves. That there was a close connection between Japan and Korea from very ancient times is a matter of history; and it is almost certain that this connection was even more close and vital in prehistoric times. The languages of the two countries are closely allied in origin, and this relationship also appears to have existed between the cultures of the two countries even before the introduction of Buddhism and its attendant Chinese civilization. Further archaeological work in this area would undoubtedly throw much light upon the problems connected with the origin of the Japanese people.

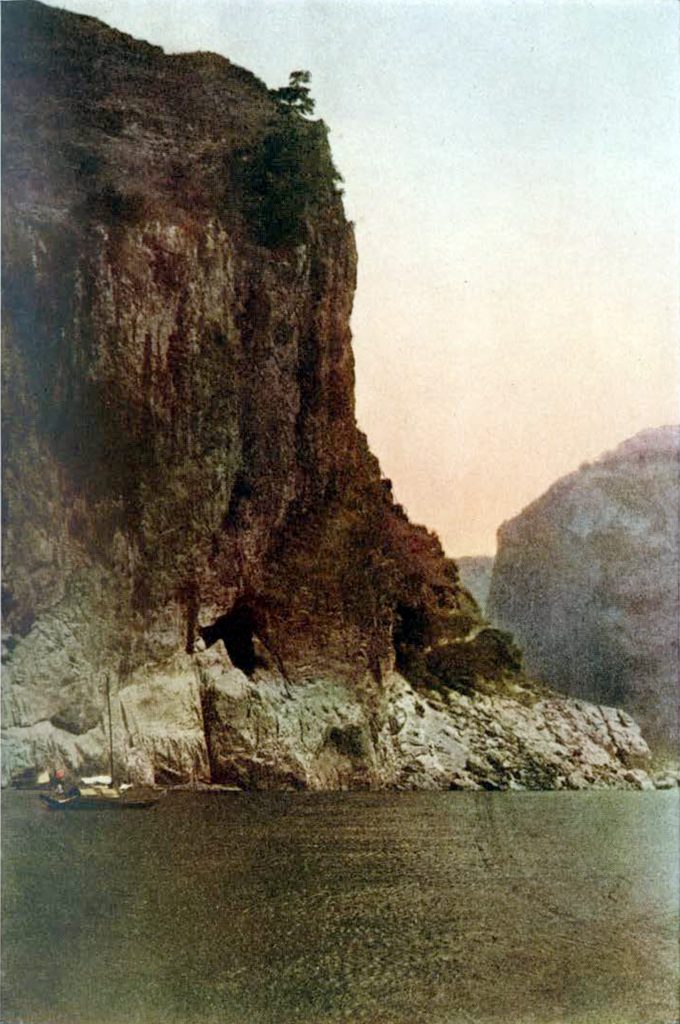

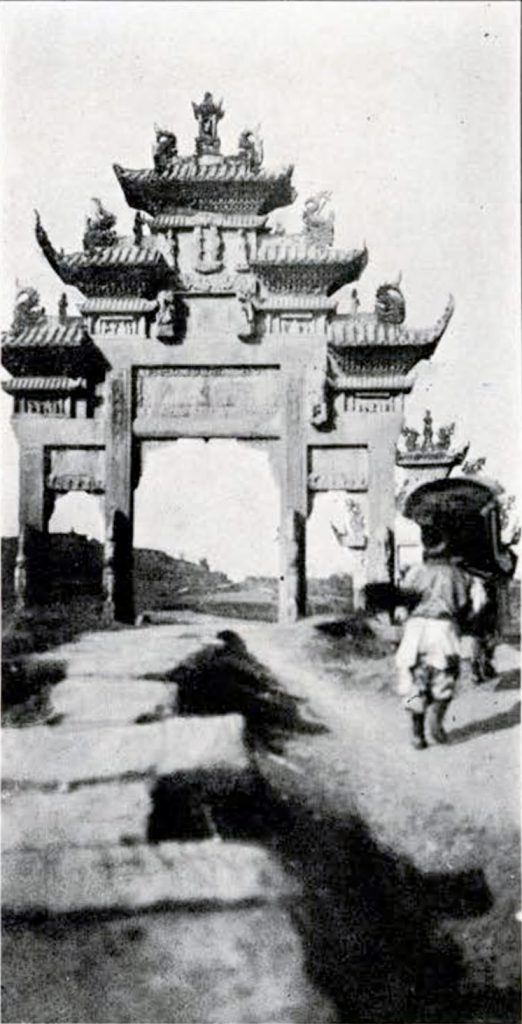

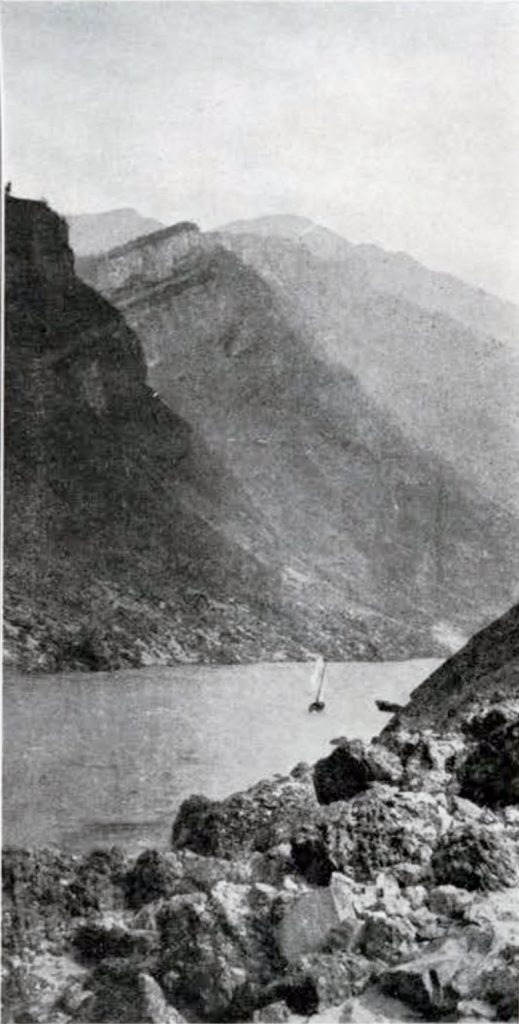

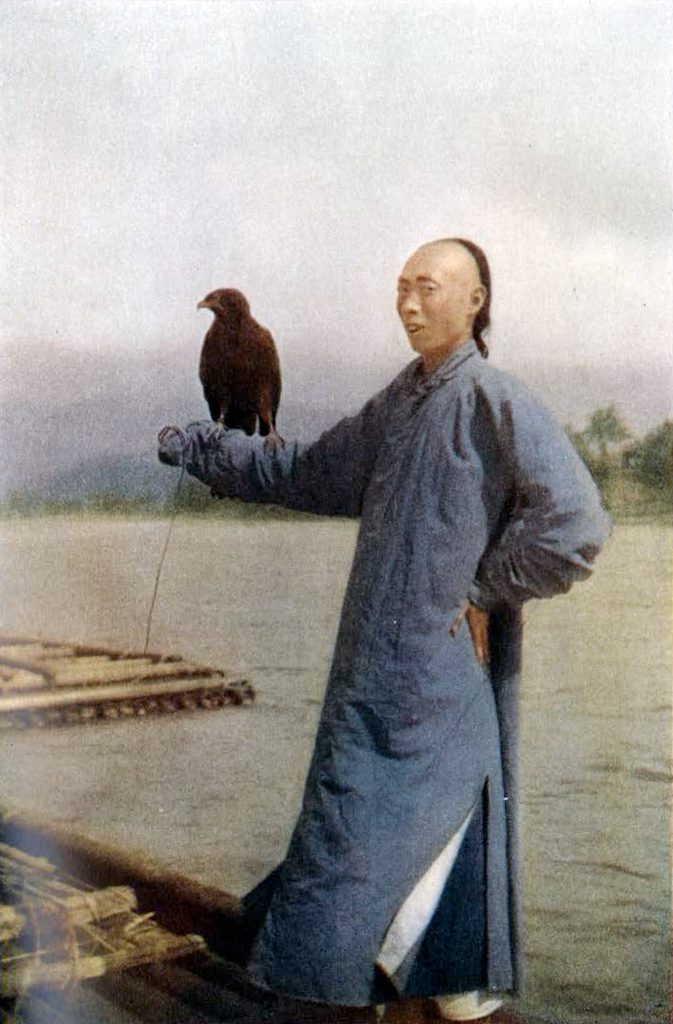

From Seoul I went on to Peking, paying a brief visit to the Liaotung Peninsula en route, and began making arrangements for a trip into the interior of China. As indicated above, one of the areas which it was particularly desired to study was that of the valley of the upper Yellow River, the earliest seat of the Chinese Empire. I hoped to travel thither direct from Peking, and after concluding my investigations in that region, to proceed on over the mountains into the distant western province of Szech’uan, following the ancient tribute road that connects Lhasa with Peking. Conditions in the region which I wished to visit, however, were so disturbed at that time, and brigandage was so prevalent, that upon the advice of those best in a position to know, I gave up the proposed journey. As an alternative, I decided to go direct to Szech’uan by way of the Yangtse River. It was my very great good fortune, as I was upon the eve of leaving, to form the acquaintance of a young New Zealander, Mr. A.R. Luckie, eleven years in China, and then on the point of leaving for his post in connection with the Government Salt Gabelle, in Szech’uan. We traveled together by rail to Hankow, and thence up the Yangtse, through flat, monotonous, alluvial country, to Ichang, at the entrance to the famous Yangtse Gorges. Here we were fortunate enough to secure passage on the little up-river steamer “Shutung,” just leaving upon her last trip for the season. Large bodies of disbanded soldiers have been marauding in this region for some time, hence it was considered necessary to tie up every night at a garrison town, and we also carried a guard of soldiers on board. However, we arrived at Chungking, some fourteen hundred miles from the sea, without incident, early in December, and proceeded to make our preparations for going further into the interior. Mr. Luckie aided me with my outfitting, and I found his knowledge of local conditions most helpful. Among other things for which I am indebted to him was his finding me a “boy” to accompany me on my travels. An interpreter is an expensive luxury, which I was able to forego, inasmuch as the “boy” Mr. Luckie hired for me had passed five years upon a British gunboat, and had a very good knowledge of English. Tung, as he was named, proved most faithful and efficient, and it was in large measure due to his loyalty and his ability in managing my other men that I was able to carry on my work in west China in a satisfactory manner.

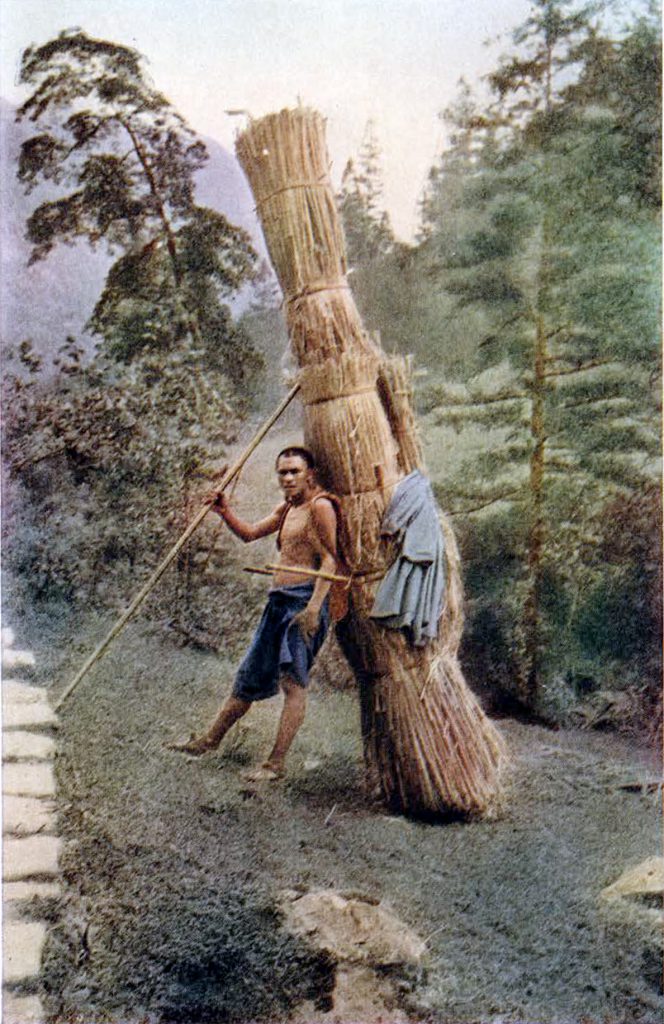

Image Number: 2023

The two hundred and sixty miles to the provincial capital, Ch’êng-tu, I covered in ten days, traveling in a so-called “four man” chair, that is to say, a chair carried by four men. These carriers do not walk two abreast, as seems to be the prevailing impression, but in single file, the ends of the long chair poles being slung to short carrying poles supported on the men’s shoulders. Carried in this way it is quite possible to read, write, or sleep, and the sole drawback is the slowness of the rate of travel. My “boy” Tung traveled in a “three man” chair, and my coolies brought up the rear with the necessary equipment. On account of the disturbed state of the country it was necessary to take an escort of provincial soldiers, but as these traveled for much of the way in wheelbarrows, holding blue cotton parasols over their heads and fanning themselves, while coolie boys, who might be hundreds of yards ahead or behind, carried their rifles and bandoliers, their protective efficacy was problematical. They were necessary, however, for if I had traveled without them, the government could have disclaimed all responsibility in case of an attack by the local banditti.

The country in eastern Szech’uan is variegated, long stretches of flooded rice fields being interspersed with red sandstone hills carefully terraced for cultivation. But little ground is lost, save that devoted to graves, clusters of which occur every few hundred feet. It has been customary from ancient times in China to level all graves at the installation of a new dynasty; but the Manchus omitted to do this, and the result is that the surface of China is cumbered with graves dating back in some cases for five hundred years. An incredible amount of the best agricultural land is in this way withdrawn from production.

The Szech’uan farmsteads were distinctly picturesque. Built usually upon some hillside, surrounded by clumps of tall and plume-like bamboos, they form a type characteristic of the region. In general they are one or two stories in height, the external walls, of white plaster, divided into panels by the upright timbers and their horizontal connecting beams. Often the fences about the buildings, the walls of the sheds, and even the nearby trees, would be festooned with sweet potato vines, drying for winter fodder.

The greatest drawback to travel in the interior of China, always excepting the matter of finances, is undoubtedly the foul and uncomfortable condition of the wayside inns. Probably they are no worse than those which travelers in Europe took as a matter of course not so many centuries ago, and their condition will rapidly mend—is mending now, in fact, wherever the country has come much under outside influences. Nevertheless it is still quite the usual thing for the best room, which is invariably located at the opposite end of the courtyard from the front gate, to be situated beside the pigsty, with merely a loose board partition reaching only part way to the roof, to indicate where one apartment ends and the other commences.

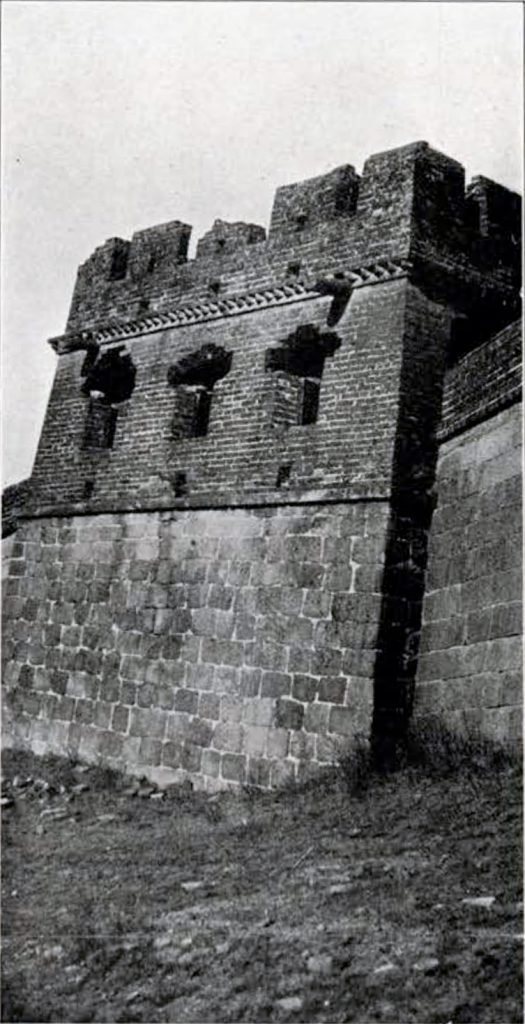

It was not long before I began seeing in the sandstone hills here and there examples of the caves which I had come to study. These caves, which are of artificial formation, are attributed by local tradition to the Man-tse, or aboriginal barbarians, and are regarded as having been excavated to serve as dwellings. This portion of Szech’uan, once comprised in the ancient kingdom of Shuh, was, in times preceding the third century B.C., quite outside the sphere of Chinese political influence centering upon the upper Yellow River, and it was only through the conquests effected by the great Ts’in Shih Hwang Ti, the builder of the Great Wall and the founder of the Chinese Empire as we know it today, that this western region became an integral portion of China. The whole section is one of the deepest historical and archeological interest, and will abundantly repay prolonged and intensive study.

Upon my arrival in Ch’êng-tu I at once set to work securing all available information regarding the caves and their former occupants. There is a charming foreign community in Ch’êng-tu, in which both the lay and the missionary element are represented by some of the finest examples of each class that it has been my good fortune to meet anywhere. All with whom I came in contact were most kind and helpful, and if I single out for mention Messrs. W.N. Fergusson and Thomas Torrance, it is simply because these two gentlemen have made special studies of the archæology and ethnology of Szech’uan, and accordingly were particularly well able to afford me the information for which I was seeking.

During my stay in Ch’êng-tu I rode out to Kuan Hsien, some forty miles to the northwest, at the edge of the so-called Tribes Country of western Szech’uan, a region still occupied by the aborigines of western China, hardy mountaineers with a culture of their own which deserves far closer study than has hitherto been given to it. The city of Kuan Hsien marks the point where the Min River bursts forth from the mountains to water the rich Ch’êng-tu basin, and it is here that one of the world’s most important irrigation systems is installed. The work, which included the cutting through of a lofty ridge of solid conglomerate and the taming of a hitherto uncontrollable river, was carried out in the reign of the great Shih Hwang Ti, from whom not merely the Great Wall but everything else of consequence in China seems to date. The two men, father and son, who carried out the work are commemorated by a temple erected to them, overlooking the Dragon Pool and the great cutting above mentioned. The river beds are yearly cleaned out at this point, and their banks strengthened with walls and long “snake baskets” of interlaced bamboo, filled with stones and laid side by side in long even ranks. This work was in progress at the time of my visit, and is done, curiously enough, by members of the aboriginal tribes, who appear more expert in stonework than the Chinese. This fact may not be without its significance in connection with the prevalent belief that the famous caves are the work of their ancestors.

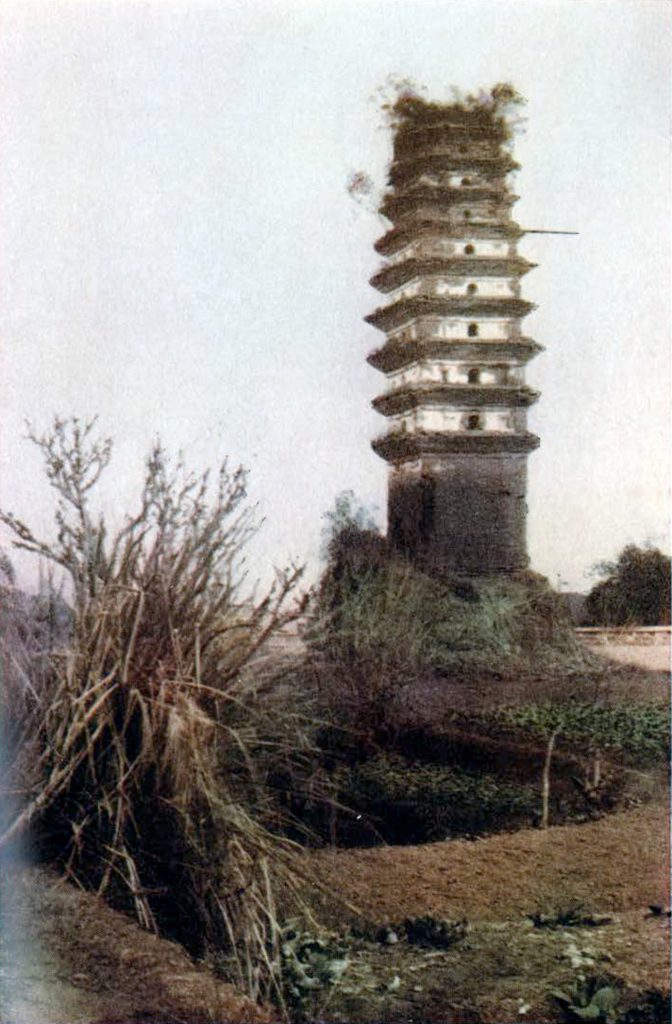

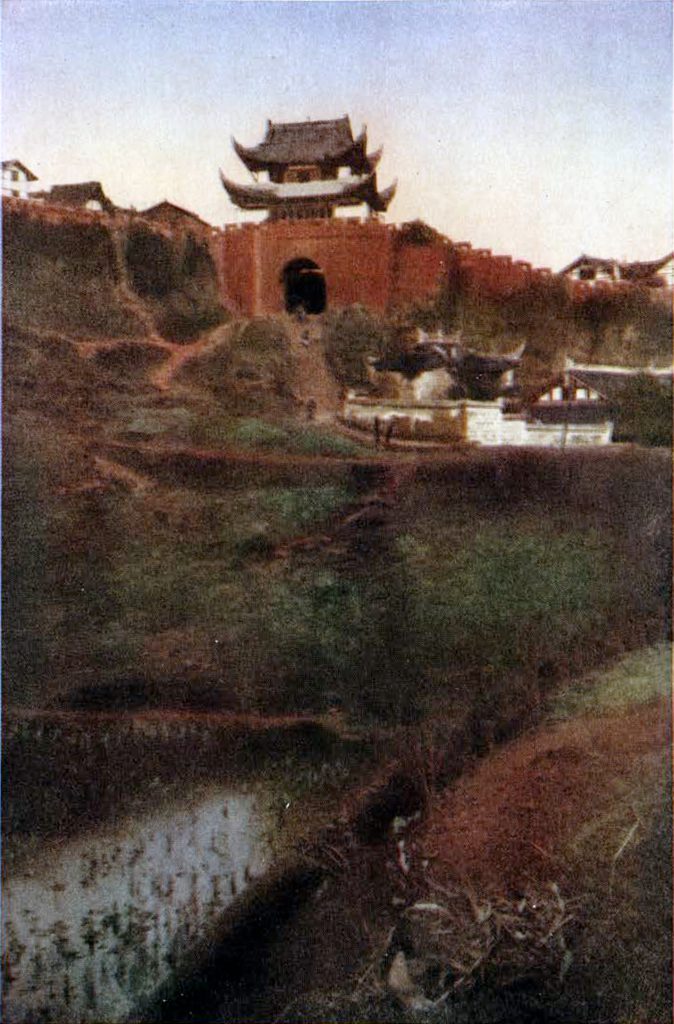

Image Number: 2024

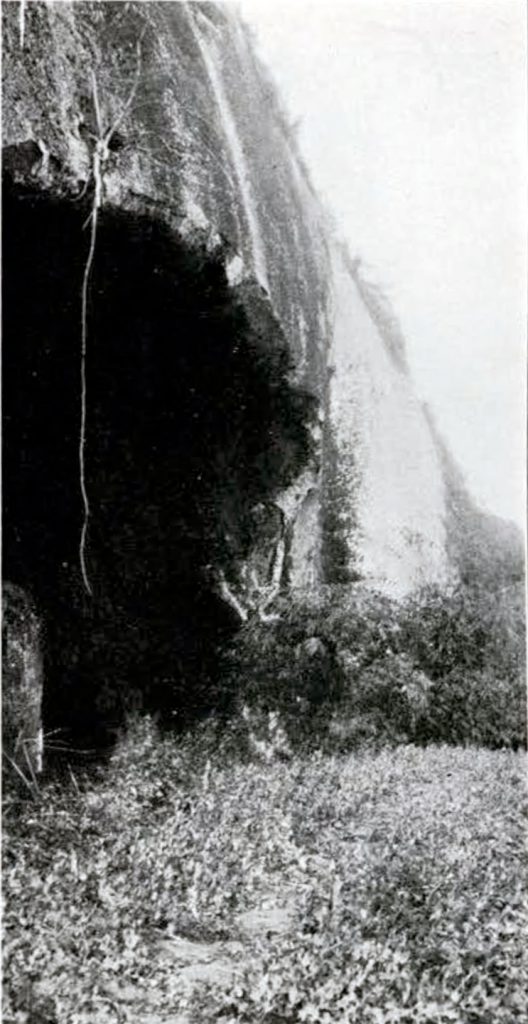

Early in January I left Ch’êng-tu and went by chair through the picturesque valley of the Min to the city of Kiating Fu, at the junction with the Ya River. It was in this section, I had been informed, that the caves were to be found in the greatest profusion and the most elaborate forms. Here, among others, I met the Rev. A.P. Quirmbach, who, although one of the busiest men in west China, placed his time and one of his saddle horses at my disposal, and devoted two days to guiding me to the more important cave groups of the region. The rock here is of the same soft red sandstone that occurs so widely in the province, and in many places is actually honeycombed with these caves.

The known caves are of course all rifled and their contents either scattered or destroyed by the plunderers. From time to time, however, hitherto unknown ones are coming to light, with their contents undisturbed. These show us that it was customary to bury the dead in stone or earthenware coffins, accompanied by clay images of wives, slaves, and tutelary spirits (if we can interpret as such certain grotesque animal-headed figures). Objects of iron and bronze also occur. “There are besides,” to quote Mr. Torrance, “models of houses, cooking pots, boilers, rice steamers, bowls, basins, vases, trays, jars, lamps, musical instruments, dogs, cats, horses, cows, sheep, fowl, ducks, etc.” Among other things cash are frequently buried with the corpse. These, of course, together with anything else which can be turned to profit, are at once hypothecated by the grave robbers; and then, with the vandalism which is so noted a trait of the Chinese peasant character, they proceed to smash most thoroughly and systematically everything breakable. As an example of this, Mr. Torrance showed me in Ch’êng-tu in his collection a most beautifully modeled terra-cotta leg and foot, with sandal attached, and beside it something apparently meant for a spearhead. This fragment, he told me, came from a perfect statue, about half life size, found by Chinese peasants and smashed to fragments by them out of sheer perversity.

This state of affairs is quite general over China. There is scarcely a historic monument that has not been wantonly defaced by the very people who should by rights have most closely cherished it. It is this that makes so exasperating the misguided activities of those busybodies who, from motives of self advertisement, have been endeavoring of late years to prevent the gathering for purposes of preservation and scientific study of Chinese archæological specimens.

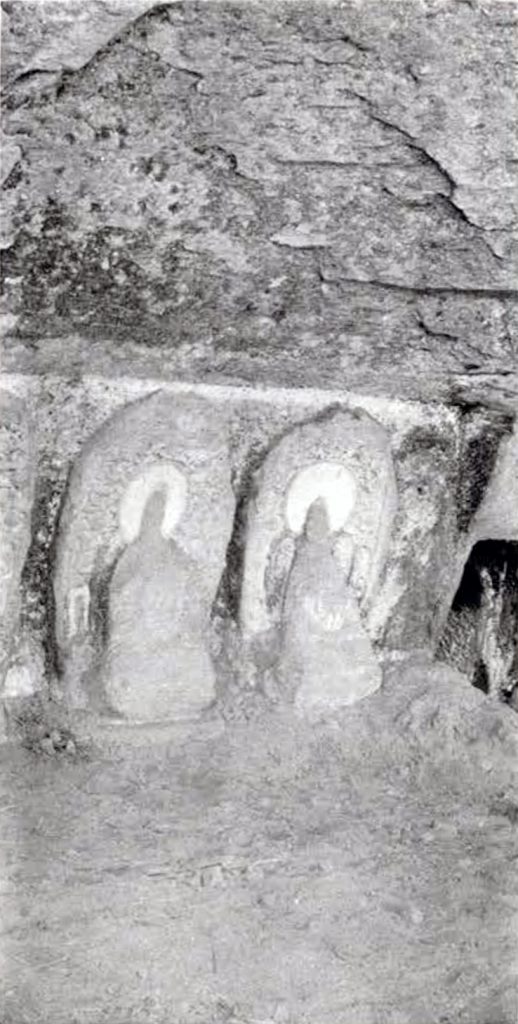

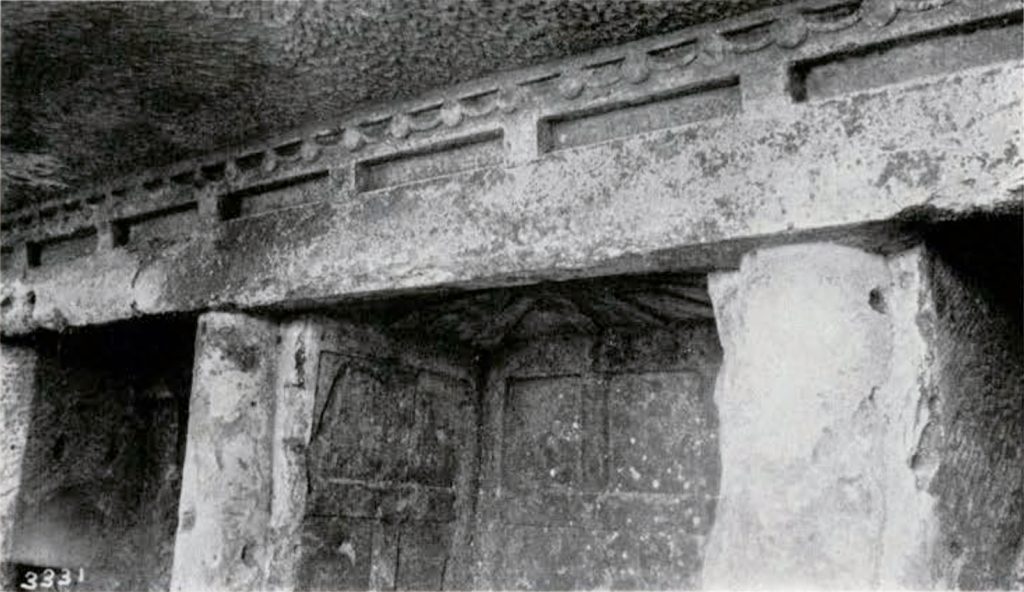

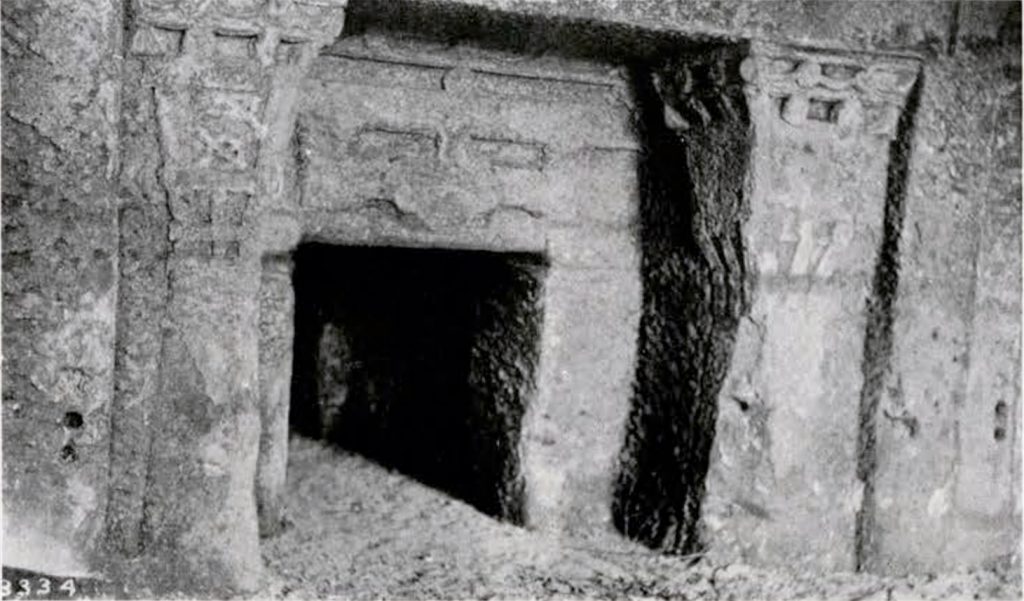

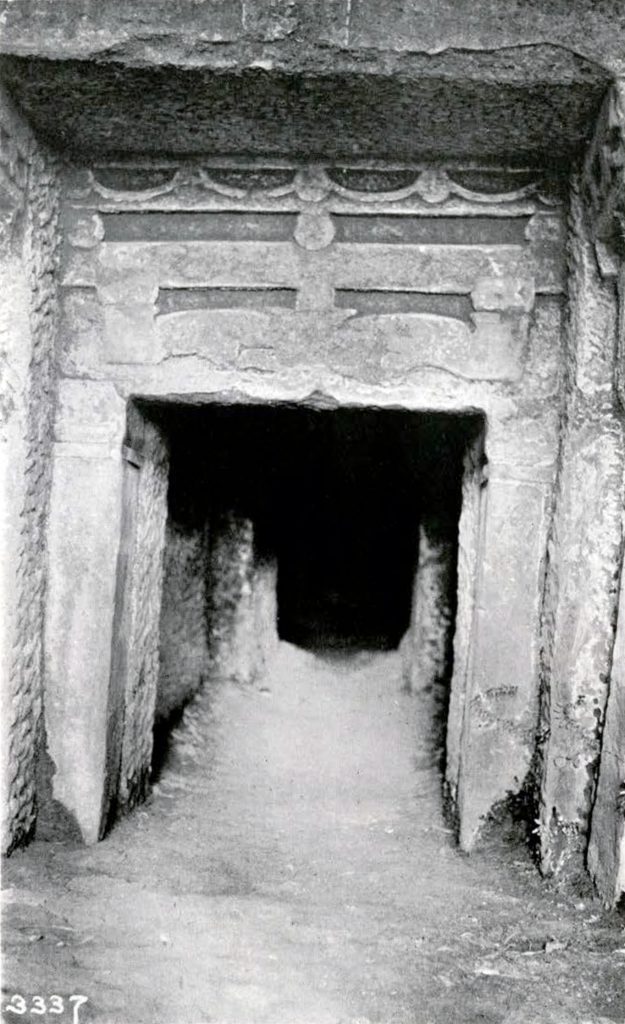

A careful examination of the caves in the region about Kiating Fu, coupled with the information which I was able to gather from various sources, suggests three points which might seem to confirm the popular tradition ascribing them to the aborigines. In the first place, the caves are found not only in the portions of Szech’uan occupied by the Chinese, but at least four days’ journey into the Tribes Country, in a district wholly occupied by the aborigines, who have maintained their own culture in unbroken continuity from prehistoric times. Secondly, not one of the caves that I saw, and none that I heard of, has any inscription whatsoever having to do with the purpose for which it was excavated. There are, it is true, Chinese inscriptions of relatively late date, recording the visit of important people to some of the larger caves, which were even then apparently quite as great curiosities as now; the earliest of these inscriptions that I saw was dated in the northern Sung period, in the year 1078 A.D., and, like many others, was chiseled directly over the ornamentation that had been applied to the wall of the cave by the original excavators. The third line of evidence is that all my Chinese friends to whom I have submitted the photographs which I succeeded in taking have agreed that the style of mural decoration shown was quite unlike anything ever evolved by the Chinese. In this connection, when I showed the same photographs to an American architect, he at once pointed out that the style of ornamentation was based upon a well-developed architecture in wood; that the columns and paneling and rafters, utterly functionless in a cave, were evidently the sort of thing to which the cave diggers were accustomed in their ordinary edifices. Certainly no one who was digging out a cave as a dwelling place would think of carving out two elaborately chiseled pillars flanking the entrance. If, on the other hand, he were excavating a place in which to lay away his dead, what would be more natural than to pattern it after the sort of dwelling to which the deceased had been accustomed in life?

Image Number: 4336

The great majority of the caves are simply square tunnels driven into the face of the cliff, usually with the entrances slightly recessed. Between this and the more elaborate ones are all degrees of variation. The largest which I saw consisted of a great antechamber, profusely decorated with panelings, running ornamentation, and other designs, and with several tunnels branching off. These tunnels again were in many cases bordered on one or both sides by recesses cut in the rock, as if for the reception of sarcophagi. I have no space for a full discussion of the many interesting details found in the caves; but it is perhaps enough to say that it appears to me that the native tradition is justified in so far as it ascribes the origin of the caves to the old Man-tse, but that they were intended as shelters, not for the living, but for the dead. To their date there is no clue whatsoever, to my present knowledge. It seems certain, however, that they were dug long before the earliest introduction of Buddhism into the region, and probably before the province became Chinese, either politically or culturally. Buddhist statues are, it is true, sometimes found in the caves, always, I believe, mutilated by the native Chinese; but these are evidently of far later origin than the caves. In the latter the ornamentation is almost invariably geometric, although animal designs occur, usually in a highly conventionalized form. In one case I found over the mouth of one of the smaller caves a wonderfully well-executed head of a wild ram, about half life-size. At present the more accessible caves are used by the peasantry as granaries, storehouses, and stables for their goats and buffaloes.

Image Number: 4328

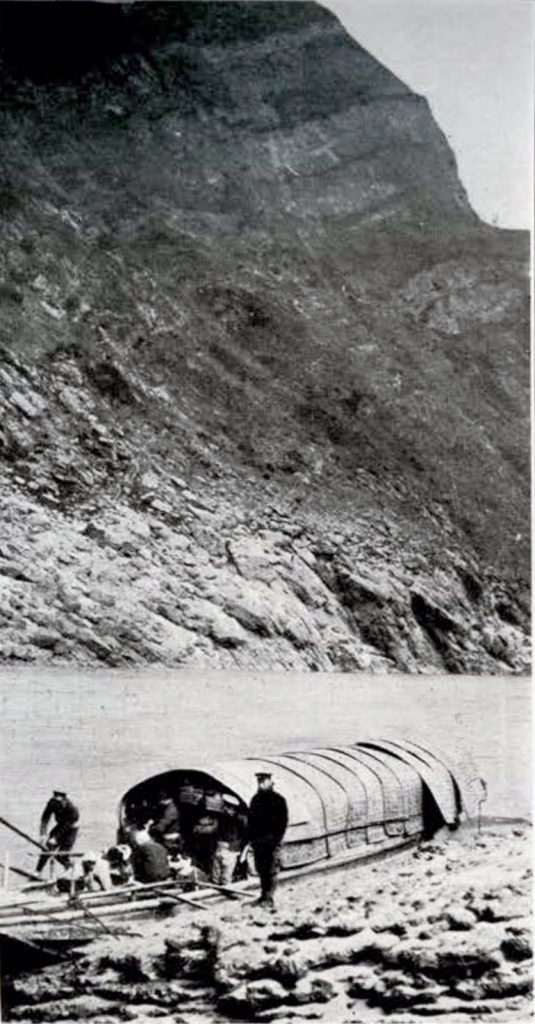

It had been my plan to return to the coast after the completion of my work in Szech’uan by way of the province of Yunnan and French Indo-China. The outbreak of the antimonarchical movement in Yunnan, in December, however, caused me to change my plans, and to decide upon returning as I had come, by way of the Yangtse. All the boats along the Min were being commandeered by the provincial authorities in order to rush troops down to meet the insurgents from Yunnan, and it was accordingly with the greatest difficulty that I succeeded in chartering a rotten and leaky old tub that had been refused by the local government as unsafe. Bad omens were not wanting. Before going aboard I saw a floating corpse. I started on the thirteenth of the month. And when I came on board my men hoisted my American flag union down—the immemorial signal of distress and disaster.

Between Kiating Fu and Chungking, a distance of perhaps four hundred miles, there are at low water seventy-six rapids, and upon the fourth of these I was wrecked. The crew and my military escort promptly jumped ashore as the boat struck the rocks; the great steering sweep and all the oars save two were carried away, and the water began to pour in through several holes in the rotten planking. My boy Tung, however, loyally seconded by my “number two boy,” Kung, who had great difficulty in keeping the blood out of his eyes from a bad cut in the forehead, manned the two remaining oars and beached the boat just as she sank, in the slack water at the foot of the rapid.

Image Number: 4338

Eventually we succeeded in patching the boat so that we were able to keep her above water by bailing night and day. Then my crew deserted, on the ground that our craft was unseaworthy (a point in which I heartily concurred with them), so I installed my chair coolies at the oars, and eventually we limped into Chungking, when I was able to remove my clothes and lie down for a good sleep for the first time in eight days.

From Chungking I proceeded down the river to Shanghai, and thence to Hongkong, Canton, and Macao, investigating the possibilities of those places from the collector’s standpoint. I then returned direct to Peking, whence, after settling my affairs and bidding farewell to a host of friends, both Chinese and foreign, who had shown me every kindness, and for whom I had come to have feelings of the warmest attachment, I left for Yokohama, sailing thence for Vancouver late in April, just fifteen months after leaving San Francisco on my outward voyage.

C. W. B

Image Number: 4331

Image Number: 4300

Image Number: 4311

Image Number: 4372