In Babylonian religion the rituals of the private confessional and atonement were characterized by mystic and magic ceremonies accompanied by prayers usually recited by the penitent. The world has inherited a large number of these private rituals and prayers, which often combine pure religious sentiment with a high degree of literary perfection. Dr. Myhrman has published one such tablet (No. 1519) in the Museum’s collection. It contains a prayer of the ill-fated king of Babylon, Shamash-shum-ukin, the Sammuges of the Greeks, who ruled as suzerain of Asurbanipal, king of Assyria, from 668 to 647 B.C. No ritual is mentioned, but we know from the official directions, written for the guidance of the priests who directed the ceremonies of atonement, that these rituals were prescribed in such cases upon separate tablets.

The Museum possesses also a much larger tablet (No. 1203) originally containing at least one hundred lines, written for a private confessional of this same king, but of a more mystic character than No. 1519. It contains a ritual which continued for two days.

Museum Object Number: B4552

The name Shamash-shum-ukin is associated with one of the greatest of historical tragedies. Being the eldest son of Asarhaddon he failed to receive recognition from his father and the court advisers in Nineveh as successor to the throne of Assyria, probably because his mother was a Babylonian princess. In consequence his younger brother the famous Asurbanipal, the Sardanapahis of the Greeks, became king of Assyria and of the vast Assyrian empire, including all of Babylonia which had been conquered and reduced to an Assyrian dependency by Senecherib, father of Asarhaddon. Asurbanipal appointed his brother Shamash-shum-ukin to the ancient throne of Babylon, where he ruled for sixteen years as a loyal representative of sovereign Assyria. If the great southern kingdom had remained faithful to the Sargonic dynasty at Nineveh this powerful Semitic empire might have resisted the less civilized Persian hosts of Cyrus and the culture of the Assyro-Babylonian peoples might have endured far into the Christian era. In that event the history of the world would have been different. But yielding to the ever-rebellious rebellious tendencies of Babylonian and Elamitic intriguers, Sha-mash-shum-ukin organized a vast rebellion in 652 B.C., involving all the discontented elements of the Assyrian empire. After five years of a horrible civil war, Babylon was captured and the unfortunate son of Asarhaddon perished in the flames.

The inscriptions of this king of Babylon are scant. The text published by Myhrman and the one to which attention is now first called are the only known documents written for the king’s use in his private devotions. Both were purchased by the Museum in 1898. The prayer on tablet 1519 was copied into the prayer books of Assyria, where it was used by ordinary laymen with omission of the six lines which refer to Shamash-shum-ukin. Addressed to the sun god it appears to contain references to the civil war.

“The wide dwelling peoples, they the dark heads, sing of thy heroism.

The lonely man thou didst cause to have a comrade.

Unto the unfortunate man thou hast given an heir.

For those in bondage thou hast opened the bar of heaven.

For those that see not thou makest light.

The obscure tablet, the unrevealed thou readest.

On the sheep’s liver thou causest oracles to be written.

Oh judge of the gods lord of the heaven spirits.”

These lines serve as an excellent example of the kind of prayers employed in the Babylonian rituals of atonement and in their religion.

The large tablet 1203 illustrates a very different type of atonement. The service is accompanied by much magic and the long address of Shamash-shum-ukin to the fire god and the sun god is based almost entirely upon demonology and symbolic magic. The text illustrates how ineradicable these ancient beliefs in devils and magic are in every great religion. On the one hand, the king in this text addresses the sun god in a prayer of the most spiritual type for his sins, transgressions and political troubles. On the other hand, the same text is one of the best examples of atonement by symbolic magic.

To rightly understand the importance of this newly discovered tablet, a few details concerning the mystic rituals should be explained. The priests of magic who presided over all the rituals of private atonement possessed two long series of incantations in which the sinner was purged, healed and atoned by fire. These were known as the Maklû or “Burning” ritual and the Shurpu or “Fire” ritual. When these rituals were employed the penitent usually made images. in tallow, dough, wood, etc., of the devils, witches and evil spirits which he supposed had obtained possession of his body. And as he burned these images in fire he recited curses against the demons. By sympathetic magic he thus supposed that the devils themselves were consumed in fire and driven from his body. The ritual written for the use of Shamash-shum-ukin is apparently based entirely upon the great Maklû series, and many lines of that well-known book of incantations are restored by means of the new text.

In his long address of over seventy lines the king complains in the following terms.

“They encompassed the earth at my feet, the measure of my form they measured.

Images of me, be it of tamarisk, cedar, tallow or honey, lo they made.

Images of me in a cavern in the west they concealed.

Images of me in a potter’s oven they burned.

Images of me at the crossways they concealed.

Oh may the sun god break the sorcery of my sorcerer and sorceress, of my wizard and witch.

May (the fire god and the sun god) catch them at their evil doings and shatter them like an earthen jar.

May they die and I live.

May they quake and I stand fast.

May they be bound and I be freed.

By thy command, which is a thing divine, and changes not, and by thy true grace which alters not

I Shamash-shum-ukin, son of his god, thy servant would live and prosper.

Thy greatness I will extol, thy praise unto wide dwelling peoples I will sing.

Oh sun god exalt the magic curse which Nudimmud, counsellor of the gods, has made.”

According to the ritualistic directions attached to this incantation the priest made fifteen images of fifteen devils from tallow, dough, clay, etc. and burned them on a censer, while the king recited his long list of grievances and petition to the fire and sun gods. Thus the Babylonians cast out devils. As the images of the demons melted in the flames of the fire god they themselves rushed from the body of the sinner as he prayed and left him pure and at peace with his god.

The famous legend of the seven devils current in antiquity was of Babylonian origin, and belief in these evil spirits who fought against the gods for the possession of the souls and bodies of men was widespread throughout the lands of the Mediterranean basin. Here is one of the best known descriptions of the seven demons; the text is imperfect.

“Of the seven the first is the south wind. . . .

The second is a dragon whose open mouth . . .

The third is a panther whose mouth spares not.

The fourth is a frightful python . . .

The fifth is a wrathful . . . who knows no turning back.

The sixth is an onrushing . . . who against god and king [attacks].

The seventh is a hurricane, an evil wind which [has no mercy].

The Babylonians were inconsistent in their description of the seven devils, describing them in various passages in different ways. In fact they actually conceived of a very large number of these demons and their visions of the other evil spirits are innumerable. According to the incantation of Shamash-shum-ukin fifteen evil spirits had come into his body and

“My god who walks at my side they drove away.”

The reader has observed in a citation above that the king calls himself “the son of his god.” We have here one of the most fundamental doctrines of Babylonian theology, borrowed originally from the religious beliefs of the Sumerians. For them man in his natural condition, at peace with the gods and in a state of atonement, is protected by a divine spirit whom they conceived of as dwelling in their bodies along with their souls or “the breath of life.” In many ways the Egyptians held the same doctrine, in their belief concerning the Ka or the soul’s double. According to the beliefs of the Sumerians and Babylonians these devils, evil spirits and all evil powers stand forever waiting to attach the divine genius with each man. By means of insinuating snares they entrap mankind in the meshes of their magic. They secure possession of his soul and body by leading him into sin, or bringing him into contact with tabooed things, or by overcoming his divine protector with sympathetic magic, which Shamash-shum-ukin complains about in the tablet. These adversaries of humanity thus expel a man’s god, or genius and occupy his body. These rituals of atonement have as their primary object the ejection of the demons and the restoration of the divine protector. Many of the prayers end with the petition, “Into the kind hands of his god and goddess restore him.”

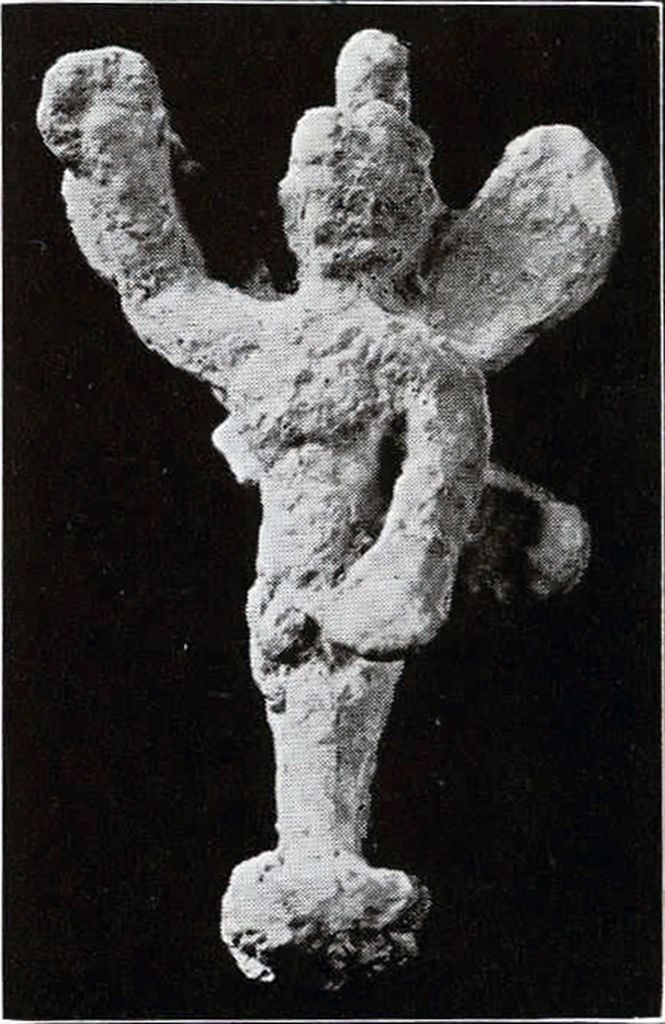

Representations of the seven devils are somewhat rare. The University Museum possesses one of the three known figurines which represent a demon of the wind. It has, like the wind demon of the Louvre and that of the British Museum, four wings extending from the back shoulder blades. The British Museum figurine represents the demon of the winds with body of a dog, scorpion tail, bird legs and feet. Its upper limbs, those of a dog, are represented in the same attitude as in the figurine in this Museum. The head, however, is a mythical composition, half human, half dog, with savage aspect, huge grinning mouth, flat nose and wide ears. The Louvre demon has the same bird legs and claws, the same four wings but the lean gaunt body is human, and so are the hands, represented in the same attitude, the right raised to attack the soul of man and the left held hanging tensely, ready to hold its prey. The head of the Louvre demon has the horrible aspect of a mad creature, half dog, half human, with snarled mouth showing two long canine teeth. The figurine in the University Museum resembles closely that of the British Museum and probably represents the demon of the south wind, the spirit of the hurricanes which blew across Mesopotamia from the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. The upraised right paw and the awaiting left paw are clearly those of a dog, and the lower limbs terminate in heavy bird claws. As to the lower limbs themselves, there does not seem to be any indication of feathers, but one expects more aviative characteristics in a figure which represents the wind and we may suppose that the oxidation has obscured their birdlike character. The body is apparently that of a dog and it has a scorpion tail similar to the figure of the British Museum. The head, however, resembles the horrible menacing composition of the Louvre demon.

On the head of each of these three known figures of the wind demons is attached a small pierced disk. The owner probably passed a string through this aperture and hung the figure in his house as a charm against the demons. Nevertheless each is posed upon a small platform which enabled the figure to stand wherever it was placed.

S.L.