The Yoruba tribes of the hinterland of Lagos in the Western Province of Southern Nigeria were formerly united in a powerful state under an Alafin or King who had his capital at Old Oyo. The Yoruba kingdom was at the height of its power about the end of the seventeenth century, though even as late as 1818 the Dahomi were paying tribute to the Alafin of Oyo. In its palmiest days the kingdom laid all its neighbors, including the Hausa, under tribute.

Pressure of the Mohammedan tribes from without, aided by internal dissensions, destroyed the unity of the kingdom. During the last two-thirds of the nineteenth century it became a congeries of mutually hostile petty states, pacification of which was only accomplished when the greater part of Yoruba land became a dependency of Great Britain about a quarter of a century ago.

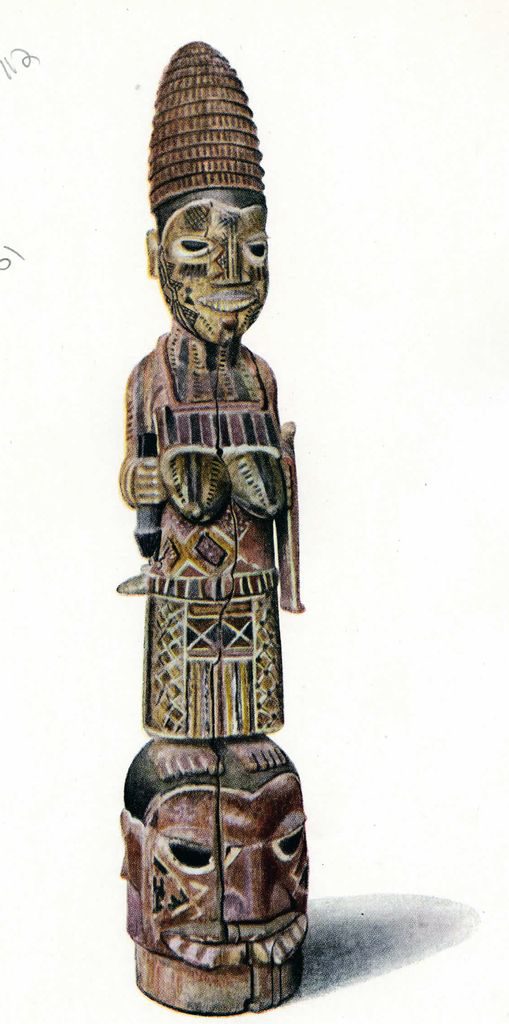

Museum Object Number: AF2002

Image Number: 718

The influence of Islam, exerted upon the Yorubans for many generations, seems to have made itself felt much less in their religious than in their civil life. A Yoruba legend relates the coming of a Hausa Mussulman to Ife, their holy city, to preach Allah to the people, and Islamic cults have perhaps to some extent modified certain of their religious beliefs. Yet they have remained essentially pagan. Frobenius (1907) speaks of a “ritual murder” having taken place during his visit to Ibadan almost under the eyes of the Resident and, so to speak, between church days. But Yoruba land was never drenched with the blood of human victims as were Dahomey or Benin, so far as we know from any historical records. The people of Ibadan, indeed, were so averse from this form of ceremonial cruelty, that upon an occasion when the immolation of a slave was considered indispensable they used to pay the priests of Ife to perform the sacrifice vicariously in the latter town.

The high gods of the Yoruba are called orisha, the deified deceased. Every Yoruba is descended from an orisha with whom his connection is so intimate that he considers himself at once a portion and a representative of the god—a portion, in that, dying, he returns to the orisha, and a representative, since every newborn child is a reincarnation of some deceased member of the family claiming descent from that orisha. Each orisha is thus the head of a clan, and since his descendants may not marry among themselves, a man must take his wife from among the descendants of another orisha, that is, from a clan not his own.

The highest—also the most remote—of the gods is Olorun. He is a vaguely conceived god of the sky, whom no one worships nor heeds. Why should they, since he himself takes no heed of men’s affairs? The other gods are nearer to men, forefathers of the people, controlling forces useful to their posterity, whom therefore these have it at heart to placate by offerings, and to honor by worship. Such are Obatala, whom Olorun begot, and to whom he has handed over the management of the firmament and the earth; Shango, the thunder-god; Ogun, god of iron; Shankpanna, the small-pox god; Edshu, god of strife and bringer of the Ifa oracle to men.

Among all the gods only Edshu and Shango are commonly represented in the form of images. Most of the carved and painted figures of men and women of Yoruba workmanship are simply representations of priests or other persons who bring offerings to the orisha, or of the dead who are being commemorated at burial feasts.

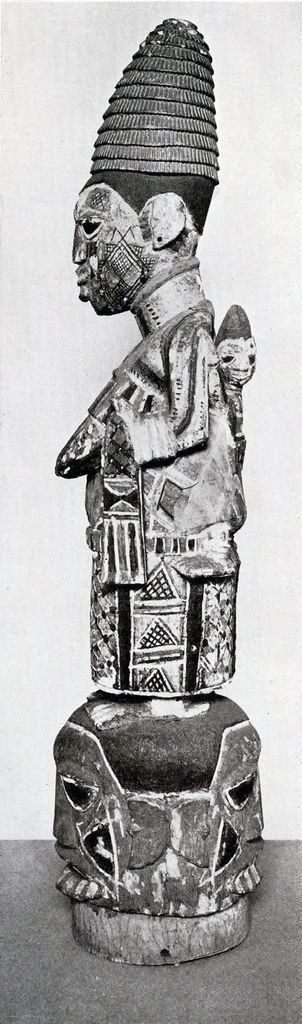

Museum Object Number: AF2001

Image Number: 712

Of three such figures in the possession of the University Museum, one, the mounted figure shown in Fig. 18, may be an image of Obatala, who, in his character of “Protector of the Town Gates,” is represented as mounted on a horse and aimed with a spear. Or it may represent one of the founders of the Yoruba kingdom, who also appear in similar state in the temple of the Ifa oracle. Or it is, perhaps, some other great chief who has more lately returned to his orisha. His great size, by comparison with that of his attendants (two of whom are men-at-arms, and the other two bearers, presumably, of booty taken in war) is in itself an indication of rank.

Figures like this, or like others in the collection, bearing on their heads open wooden bowls, form part of the accessories in the Ifa ritual. Ifa is usually called a god, though it is possible that the term properly denotes rather a cult connected with an oracle, and that myths and legends in which he is represented as a are god late accretions. There are certain facts which seem to point to the latter conclusion. No Yoruba claims descent from If a; consequently the word, which is variously said to mean “palm kernel,” “something scraped off” or “created,” is not the name of an orisha as is the case with Obatala, Shango, and the other chief gods of the Yoruba.

The ceremonies connected with the consultation of the oracle do not seem to imply the worship of a deity; and the carved figures which adorn the boards, etc., used on these occasions are representations of the orisha Edshu, who brought the oracle to men in the form of sixteen sacred palm nuts which he received from the monkeys in a palm grove. It had become necessary, it seems, to revive the flagging interest in things divine among men, for the orisha went hungry since men had ceased to sacrifice to them. So the gods, not scorning the counsel of apes, sent Edshu with the oracle to their lukewarm votaries.

In consulting the oracle the priests of Ifa employ a whitened board. The sixteen kernels are held in the right hand of the priest who acts as diviner, and allowed to drop between his fingers into the palm of the left hand. If, in this process, one nut remains in the right hand two strokes are drawn on the board; if two nuts remain, one stroke is made. This is repeated until in this manner have been produced the sixteen odu, or sacred marks, by observing the disposition of which the diviner reads the oracle. A very similar mode of divination has been reported from northern Africa, and the Ifa oracle, in its present form, is almost certainly derived from the Mohammedans.

Since the three painted wooden figures, or rather groups, pictured here all stand on hollow wooden pedestals representing either single or double human heads with holes cut through at the mouths, their use as masks is indicated, and consequently a possible connection with the cult of Egun or Egungun.

Before the burial of a corpse, the shroud which has covered it during the time it has been kept in the house is removed. A wooden mask is prepared, which represents, realistically or symbolically, the deceased. This mask is assumed by a dancer, who puts on also the dead man’s shroud. He dances before the bereaved relatives, speaks to them in a shrill, high voice, condoling with them, and discussing matters in which the dead man was interested in common with them. Offerings may afterwards be made to the mask, and it is believed that these are received by the deceased.

Image Number: 716

Museum Object Number: AF20001

“To prove to the women folk that man rises and goes to heaven, a person is placed in a private room. Then when all the family is assembled in an adjoining room someone will strike the ground three times with a stick, crying out, ‘Father! Father! Father! Answer me.’ And the Egun, the person in the room, answers, and everyone rejoices. Food has been placed in the Egun’s room by the women, and when the Egun has answered, each guest goes in there and helps himself as he or she wishes. The Egun is not dressed up when in this room, but if he wishes to go outside and join in the dancing, then he dresses himself and puts on his mask.”

Museum Object Number: AF2000

Image Number: 707

From being regarded originally as merely the incarnation of the dead, Egun has in some places developed into a kind of bogey whose function is to carry away persons who are a nuisance to their neighbors—termagants, busybodies, scandalmongers. In his public character, at any rate, his touch is fatal. To threaten an Egun with personal violence, or for a woman to speak disparagingly of him, is punishable with death.

A smaller and lighter mask consists of a head supporting a group of animal forms—a tortoise, its forelegs gripped by the beaks of two scavenger birds, and a serpent. The whole is surmounted by a covered bowl, which suggests that this object may have been used as a “fetish” or rather a “fetish” container. Snakes play an important part in the religion of most West African peoples, and birds and tortoises are objects of reverence, if not of worship. The tortoise (like the spider of West Coast myth) stands for wisdom and cunning, for special efficiency in the struggle for existence, a reputation probably due to the immunity afforded by its tough carapace from the attacks of the many foes which lie in wait for the other small creatures of the jungle. But this is not the reason assigned on the Slave Coast for the success which attends the tortoise in all his undertakings: it is a reward for a good deed cleverly performed.

The daughter of a king was deaf and dumb. The tortoise went to the king and asked what reward he would receive if he succeeded in making the girl speak. “I will divide my palace in two and give you one part,” said the king.

The tortoise took a bottle of honey and went into the wood where the child dwelt, placed the bottle where she would see it, and went and hid himself. As the child came up to take the bottle, the tortoise crept up behind and struck her a light blow. “Thief!” he cried; “that’s how you steal honey!” Apparently the shock of discovery restored the princess’s powers of hearing and speech, for she immediately burst out into indignant protests. The tortoise fastened a rope round her waist, and led her back to the palace, taunting her as they went, so that she continued to return angry and voluble rejoinders until they came into the presence of the king, who was thus assured of her complete recovery. He divided his palace into two parts and gave one to the tortoise.

That is why the tortoise succeeds in everything he undertakes.

H.U.H.