Mr. Louis Shotridge, the author of this article, was born at the old Indian town of Kluckwan on the Chilkat River. He is a full blood Chilkat and is the son of a Chief of the Eagle side. Mr. Shotridge has been a member of the Museum staff since 1912 and was sent to Alaska in 1915 to study the customs of his people, a task upon which he is still engaged.—EDITOR.

Upon my arrival in Chilkat in the summer of 1915, I immediately set to work collecting material with a view to recording for the Museum a faithful history of the Tlingit people. I proceeded in the usual way of obtaining information from the natives, which is to hire an informant. For a while I traced events one into another and continued so until I discovered inaccuracies in many polished stories. The part that many Tlingit informants play in recording myths and other data has been to a great extent commercialized. Many important stories are polished ready to be given in exchange for cash. A desire to overcome this habit forced me to scheme as to the safest way to approach the natural self of the man whom I am to represent. I took all precautions and gave myself plenty of time. Meanwhile I made frequent visits to different families in various surrounding summer camps and noted different things that are of interest.

Like many other native tribes of America, the Tlingit people are wandering step by step away from their old customs and habits. Modern influences that are the causes of the heterogeneous changes in their lives are particularly noticeable at places where European immigration is encouraged by the prospect of beginning a new life. Most of the Alaskan Indians are fascinated by the new ideas of these white people and casually adopt them. Only a few affectionately hold to the teachings of their forefathers.

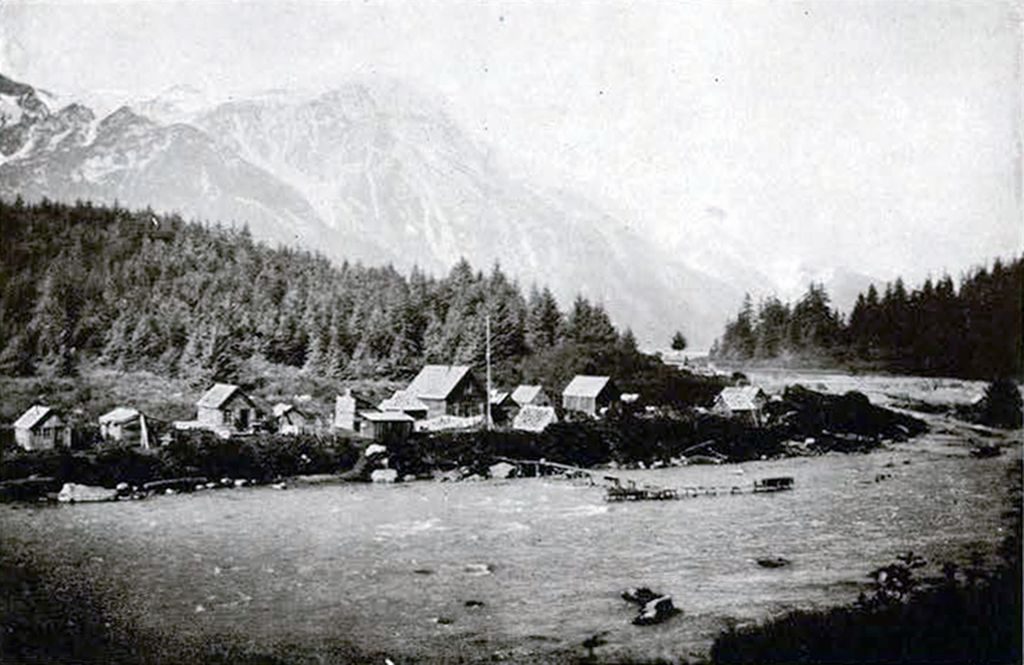

As soon as the campers started to move back to their winter quarters after the close of the summer season, I started preparing a shelter for my wife and myself in readiness for the approaching winter. We made our headquarters at Haines, a small town of about three hundred inhabitants at the mouth of the Chilkat River. From here I planned my winter trips to other villages.

In the latter part of the autumn I made my second visit to Klaku-aun, my birthplace, an ancient town situated about twenty-three miles up the Chilkat River. I came this time to pay my respects to a “Call together” ceremony, which had been proposed by my family.

The call together is a revival of what has been known as a “Drum-bearing” ceremony (interpretation of the Tlingit name for a mourning ceremony). In former times it was performed immediately after a death.

I remember clearly when I was a boy the last drum-bearing ceremony which was performed at Klaku-aun by the Gana-tedi’ clan of the Raven side. The deceased man was not of a high caste, but a member of a well to do middle class family. The body remained in his family house for four days, during which time his clansmen conducted the mourning ceremony. Customarily the relatives of the widow are called on to perform all the labor that is connected with the funeral.

After the corpse had been dressed, his hair well combed, face painted and his moccasins and mittens well secured, in short, prepared as a man for a journey, he was seated in the rear of the room and the Gana-tedi’ began to enter the room, each person presenting his own contribution of skins, blankets and other representations of currency, which were placed on a line stretched across the rear and when this was filled more lines were stretched in other conspicuous places, where each object might be seen.

The women began the first day by fasting and each had some one from her opposite side to bob her beautiful long hair at shoulder length. Two of the women were chosen to take care of the widow, to bathe and dress her. Meanwhile the men held a council, laying out plans, rehearsing speeches and songs for the occasion.

At the close of the first day a na-ka’ni (brother-in-law of the clan) was sent out to call together in the family house the clans of the Eagle side. Presently the guests began to arrive. A receiving man who had taken his position at the entrance announced individual leaders as they passed into the room. Each man was seated according to his social standing; thus when the chief of the Kaguantan (the leading clan of the Eagle side) entered, his proper place was called out : “To the rear middle, to the seat of your uncles, you are seated in the name of our uncle. . . .” (Here name of some clansman who had passed away to the land of souls was mentioned.)

On each side of the chief were seated leaders of the Shungu-kedi’ and Nays-a’di clans, and to right and left of these three men other representatives took their places, each according to his rank. When the first row had been filled the seating was continued in the second, third and fourth rows. In the meantime four introductory songs were sung.

When all the guests were seated a spokesman of the mourners delivered a speech, expressing gratitude for the favor rendered on the part of the opposite side. Meanwhile leaf tobacco was prepared in the Gana-tedi’ ceremonial pipes, each pipe bearing a name pertaining to the crest animals. At the conclusion of his speech the spokesman requested that the Raven’s servant-pipe be passed to the leading man of the Kaguan-tan, du-dji-de’ (to his hands). In the same manner other pipes were passed to all the guests. Some of the tobacco was placed in a small dish which was held over the fire while one of the directors called out many names of his clansmen who had passed away; brave men and noble men who were worthy of being remembered on all occasions of this kind. After so many men had been named to it the dish of tobacco was dropped into the fire. I used to wonder how so many souls could each have his share of so small a quantity of tobacco, but I learned later that the spirits of all things that are sent to the land of the dead in this manner are supposed to grow.

Image Number: 14771

Each mourner was then called on, to express his or her grief, which was expressed in each case by songs, sometimes preceded by brief speeches. The songs were very solemn, songs that were not sung on ordinary occasions. The mourners sang while the guests of honor smoked the large pipes until about midnight. Thus the soul of the dead one was supposed to have passed the first of the four stages of the road to the land of souls. This was repeated on four successive nights and during the four days the guests were called in regularly to partake of the foods of which the deceased man had been fond in his lifetime. No food at this time was passed to the spirit land other than what was taken from the widow’s dish which was placed always at the edge of the fire for a slow consumption. This was supposed to pass to the departing soul of her husband.

In the early morning of the fifth day the funeral took place. The corpse was tied in the form of a long bundle and by means of strong ropes was hoisted up and passed out through the smoke-hole in the roof of the house. This custom was to avoid the living persons from passing through the same exit with that of the dead. The body was then carried to a place behind the town and laid down on a large pile of firewood which had been prepared on the previous day. The cremation then took place. As the fire blazed more songs were sung, songs composed with words signifying the passing of the soul through the final stage. When the body had been incinerated the burned logs were rolled aside, the ashes gathered into a marked sack and placed in one of the wooden chests in the family grave house.

After they had fulfilled what they considered a duty toward their opposite side, the Eagle participants were called in for the last time, to be paid for their faithful services. The property that had been contributed was then taken down and counted. The skins and blankets were distributed among the guests. A formal dinner was served immediately after the final payment, during which a small portion of the food was placed on the fire in the same manner as the tobacco.

In the event of a death among the higher castes the mourning ceremony was prolonged to eight days and performed with more elaboration and formality.

A few days after the conclusion of the ceremony the widow called together all the clansmen of her deceased husband and before them the estate including all personal effects was brought out This property the widow offered to distribute among the clansmen, but the directors, contrary to her noble offer, requested that the property remain in its former state and a young nephew of the deceased man was called out to take the title of his uncle, and with unanimous good wishes of the Gana-tedi’ clan the widow entered to continue her life with the new husband. Of course all further obligations with regard to the erection of a memorial on the grave house of the rich uncle settled on the young man’s shoulders.

It will be needless to go into detail of the call together ceremony which my family performed at Klaku-aun in 1915, because some modern influence is unavoidable. However, regardless of these changes, a real Tlingit is inspired by the speeches and by the solemn behavior of the aged members of my clan, the Kaguan-tan.

I spent about two weeks at Klaku-aun, leading the life that I seemed to have left in the past.

It was not until the month of December that I decided to organize an evening story telling league at Haines. The superintendent of Alaskan schools permitted me to use the United States public school house in which our meetings were conducted two evenings a week by different native members.

Image Number: 14766, 14762

The main object of the organization was to impress on the minds of the modern Indian children the former life of the tribe to which they belong. For my part I told of my observations on life among the Caucasians and the customs and habits of other progressive races, while the older members of the league gave, with the old time spirit, narrations on various historical events and legends relative to the natural former life of the Tlingit people. In order to retain the originality of these narratives, I took my notes in a phonetic form that I hope to translate and interpret some time soon.

In the early part of the spring I went to Wrangell, a town about three hundred miles south of us, with a view to obtaining an old specimen which I learned to have been in the possession of the head family in the community there. I arrived in Wrangell only to learn of the instant death of Shakesh the chief of the family.

I took advantage of being with these people, the early history of whom is in alliance with that of the Chilkat Tlingit. I managed to gain acquaintance with some of the old people, from whom I learned much about their early connection with other Tlingits who are found in the northern direction of them.

Before midnight after the close of my third day a small mail boat carried me away from Wrangell to the tribes on Prince of Wales Island. After a few days travel I came among the Tikanaw clan of the Raven side, the enemy in gone-by days of my own clan, the Kaguan-tan. These people had recently formed a comparatively new settlement in Klawalk village. I was received by an unexpected host, a relative who had married into the Tikanaw clan and became a missionary among them. To be sure these are peaceful times for them and my clan, but I did not expect that my people had sent a missionary to our old enemies.

On the day of my arrival in Klawalk the chief of the community asked me to give his people a talk on one of the subjects that I had offered my own people in Chilkat. There were differences of opinion as to what I should give. Most of the men were very much in favor of a talk on the modern life in the progressive world of the white man. The decision, however, rested with me and as it was yet forenoon I had time to decide before the evening. After our noonday meal my host offered to go through the village with me, that I might become acquainted with some of the old families. After brief interviews with some of the old men we decided on a certain subject that we thought would be appropriate for my talk.

It was obvious that the younger people, most of whom are half white, are very much fascinated by the ways and language of the white people and as a result had organized a society called “The Alaska Brotherhood, ” which is said to have been originated somewhere farther north as “The Alaska Native Brotherhood.” Since the middle adjective “native” conflicts with their ambition to become white men, it was necessary for the Klawalks to omit it. Apparently the organization was well represented at the meeting, as I had all that I could do to come through with a talk on “Preservation of natural character.”

I waited one week in Klawalk for the mail boat, during which time I took a few notes and made a brief study of Tlingit foodstuffs of this vicinity.

From Klawalk I paid a brief visit to the Haida tribe, who are found at the southern end of the island. Our boat made a hurry call at Hydaburg, a new settlement of the tribe. Just before we left the place I met a Tlingit woman and from what I gathered from her, these people had only recently deserted their old village and moved to this place with a view to beginning a new life which necessitated abandoning all signs of the old Haida customs.

Image Number: 14774

A few hours found us at Howkan, a deserted Haida village. Only one native family and about three white missionaries were in the old village. After I took photographs of some old totem poles that are still standing, I paid a hurried visit to the family. The wife happened to be a Tlingit who appeared to enjoy our brief conversation in our mother tongue.

After two weeks’ visit among the tribes of Prince of Wales Island I landed in Ketchikan, a town of about twelve hundred inhabitants, which is said to be supported by nearly all the new industries of the territory that lure native tribes from the many surrounding villages. Most of the natives here appeared to me to be merely existing in composite with a populace of various races of the earth.

Ketchikan was formerly an ancient Tlingit village, the remains of which may yet be seen at a certain section of the present town, indicated by a few memorial totem poles standing in front of some native family houses, but these relics are almost enclosed by new rustic buildings of new settlers. I went to call on native families whom I had known to live there, but to my disappointment I found their doors closed and have learned since that my people had moved out some months past to live in a boarding house.

It is evident that the natives in this community can no longer hold on to that which has been their own from time immemorial.

Not until I learned that all the older people were out of town for their summer camps did I give up the idea of trying to obtain some information from Ketchikan. On the following morning I boarded the first northbound boat and in twenty-nine hours I arrived in Juneau, the capital of Alaska since 1906. The population here is about three times as large as that of Ketchikan and principally supported by mining. After engaging a room in one of the hotels I went to visit the Indian village which I had known in my boyhood days. When I came in view of this ancient Aku-quan village it appeared to be very much like a live mouse confronting a hungry cat. The white settlers have formed a circle around it: on the hillside in the rear of the old village are built on high stilts many new rustic buildings with their back porches protruding toward the rear gables of the old native houses, while the former canoe way is bridged by a broad boardwalk with rows of shacks.

I found the natives in the old village in no more prosperous condition than those of Ketchikan. I called on some of the families, one or two of which seem to be content with the attics of their shacks, while the lower rooms were rented by other families who apparently had missed a space for their own shanties. The men were too occupied to heed one like myself with old fashioned ideas. If not preparing firewood they would be packing lunch pails getting ready for the approaching hour on which they must start to do their turn in one of the gold mines. In one of the upper rooms we were obliged to carry on our conversation not louder than whispering for fear of awaking someone in another part of the house who may have been enjoying a nap that he had missed during his night shift at the diggings.

From what I gathered, it is obvious that the Aku-quan have yet to realize the approaching displacement of the old village which had been so dear to their forefathers, if the press for gold continues.

After four whole fruitless days among the Aku people my boat arrived and for the second time I retreated in my efforts to acquire information that may be of some value in my work.

When I returned to the Chilkat people, I fully appreciated, for the first time, the differences under which the North Pacific Coast tribes exist. We Chilkats, unlike some of the others, are as yet unnoticed, thanks to the worthless ores in the mountains surrounding our villages.

I arrived in Chilkat just in time to join in the eulachon fishing season. The primitive methods of catching and extracting the oil from the fish are still retained by the Chilkat people. The fish are brought to shore by canoe loads, emptied into pits made on the bank and left to putrefy. Each pit holds about four canoe loads of a ton capacity and there are from one to three pits to each household.

Eulachon oil is said to have been put up in much greater quantity in former times when there was much more demand for it, but since the present generation seems to be satisfied with the fair substitute of lard and bacon grease, the preparing of the ancient lubricator is left mostly to the older members of the tribe, who still favor the superiority of the oil.

After the oil supply had been placed in store most of the campers moved down to the mouth of the river, where they camped only for a few days, catching the early silver salmon with harpoons. The trawling method has been adopted by most of the Alaskan Indians, but the Chilkat fishermen seem to have more pleasure in lying in wait with their long handled spears on the Chilkat tide flats for the ripples indicating the upstream bound of the king salmon.

Many changes, of course, have taken place in our preparations for the main food preparing season of the year. Instead of setting salmon traps and making gaff hooks we line and mend our gill nets, and instead of overhauling canoes we now spend most of our time with motor engines. Regardless of all these modern conveniences, it is strange to say that the primitive schemes are holding their own among the Chilkat people.

In the early part of the summer when the Indians began to settle on their various hunting grounds, I moved out to camp with the Chilkoot families in their village, about nine and a half miles north of Haines.

I acquired a small gasoline launch which enabled me to make my trips on calm days to other camps and come to town for my supply of provisions.

Here again I lived the life which I desire to illustrate: performing the daily duties of my people and listening to their after day’s work stories, in fact, back to my boyhood days once more. In spite of our frequent associations with the white people, these old families, to my favor, took much pleasure in expressing their old time feelings and living the old life over again.

The first snow was my sign to move my camp outfit down the Chilkoot rapids and make my way back to our winter quarters.

L.S.