The tendency to worship extraordinary mortals upon whom senates and municipal governments bestowed the rank of divinity has more or less intensively characterized the history of religion. In Greece and Rome the cults of deified heroes and kings largely supplanted the worship of the older nature and cultural gods. Specialists in the religious beliefs and practices of the classical peoples appear to agree in their explanation of the appearance of this kind of worship in Greece. By the fifth century B.C. the Greeks began to lose faith in the members of the Olympic pantheon. A subtle pantheism, which appealed to that poetic and imaginative race, rapidly replaced the older belief in the anthropomorphic gods, at least among the intellectuals. And after all supremely good and able rulers had ever been their sure benefactors when the gods had failed. Popular worship has never yet been successfully conducted upon a basis of pure philosophy and consequently the worship of immortalized rulers gained ascendancy in Greece instead of pantheism. “Divinity appeared living among them,” says Wendland, and this cult acted as a medium between Stoic pantheism and mankind, says Fowler. In a measure these criticisms of two famous scholars are of universal application in human worship. Monotheism deprives man of his gods, his old religious toys and all of divine personality recedes into sublime obscurity. Or if it be a philosophic concept like pantheism, the world spirit, or pure reason which comes to occupy in the mind of man the position of supreme importance, mankind finds himself even more helpless in the construction of an efficient cult. In both of these events, in Palestine, as in Greece, the situation was solved by the worship of immortalized men, the visible medium between humanity and unseen divinity.

In Rome this deification began with the worship of the dead Cæsar, and only in a later period did they concede the rank of divinity to living men. On the contrary in Greece, Egypt and Western Asia these cults began with the worship of living men, mortals who were officially deified during their human activity. This kind of cult worship was already prevalent in the Oriental provinces of the Roman Empire even with regard to Roman emperors who were not deified in Italy before their decease. The entire institution at Rome was imported from the Greek, Egyptian and Semitic Orient, but only under stress of a philosophic and religiously skeptical situation already described, a situation which finally obtained in Rome centuries after its appearance in Greece.

Students of Greek religion have generally adopted the thesis that these cults were indigenous in Greece and they have been explained as above. At any rate this phase of worship, so important in the evolution of religion, not only thrived in the Orient long before its vogue in Greece, but occupied the position of greatest importance in the worship of the Sumerian people from the twenty-sixth to the twenty-first centuries B. C. Before 3000 B. C. ancient Sumerian city kings claimed to have been begotten by the gods and born of the goddesses. These were of course pure theological dogmas contrived by a state clergy to strengthen the royal prerogatives. Although the rulers of that period were not deified and did not receive adoration and sacrifice as gods, nevertheless their inscriptions show that their subjects believed them to be divinely sent redeemers and the vicars of the gods. They already correspond to the Greek θεοὶ σωτἣρες, the divine saviors, who became the objects of the Greek cults. And the members of the first powerful Semitic dynasty founded by Sargon at Agade about 2900 B.C.,1 also claimed divine prerogatives to rule. The fourth and fifth kings of this Semitic line, Naram-Sin and Shargalisharri were actually deified. As in Rome the deified emperors received the prefix deus, or god, so here the names of these kings of the thirtieth century B. C. are prefixed by the sign for god. We might at first infer that this institution is of Semitic origin since historically it first appears in a Semitic dynasty. But this is surely due to the paucity of our material. The cults of divine rulers are so characteristic of Sumerian religious beliefs that we cannot be in error in attributing the entire system to that source in Babylonia. However no evidence has yet been found that temples were built to these god men, sacrifices instituted and liturgies sung in their worship in that period.

It remained for the Sumerian people of the age of the dynasty of Ur (2475–2358) to develop this phase of religion to an extent almost unparalleled in the subsequent history of mankind. The Nippur Collection of our Museum has already furnished by far the most important tablets which contain liturgies sung in the cults of deified Sumerian kings. In view of the significance which this cult has for the origins of the same institutions in Greece and Rome, and for its striking similarity to much that is fundamental to Christianity and universally true in all human worship, our collection assumes a position of first importance in the history of religion. The founder of the dynasty of Ur, the so-called Ur-Engur, never received divine honors, but his son and successor, the famous Dungi, who ruled 58 years, was elevated to the rank of a god in the early years of his reign. His three successors, Bur-Sin, Gimil-Sin and Ibi-Sin all received canonization upon their accession to the throne, and they continued to receive worship after their deaths. In strange contrast to Roman procedure where the institution began by the canonization of dead heroes, in Sumer worship of dead kings was forbidden unless they had been deified while living. Evidently some kind consecration of the living mortal alone gave the possession of immortality.

Temples were built to these kings everywhere in Sumer, and our collection possesses liturgies sung in their cults at Nippur, a city over which they ruled. Sacrifices of oxen, sheep and rams were made to these god men as to the great gods themselves. We also possess seals of influential Sumerians dedicated to these god kings, Dungi, Bur-Sin and Gimil-Sin, and these seals show the deified emperors seated on thrones receiving adoration precisely as one of the great gods. The month of July was dedicated to the festival of Dungi, exactly as our July and August were named from deus Julius and deus Augustus.

Now, before mentioning our Sumerian tablets which contain liturgies sung in the worship of these god men, I shall call into brief discussion the ideas which apparently created a situation favorable to this extraordinary period of god man worship. In Sumer it certainly did not arise because the Sumerians and Semites had become skeptical regarding the powers of the great gods. In the liturgies sung in the cults of the divine men, the earth god Enlil, the sun god Babbar, the moon god Sin, the mother goddess Innini and all the others occupy the same classical positions of unlimited power and enjoy the same unrestrained confidence. The origin of god man worship in Babylonia is connected with a fundamental doctrine of ancient civilization, the belief in a dying god. Tammuz, the youthful son of mother earth, incarnation of earth’s productivity, the soul of vegetation, the flowers and flocks, suffered annually the fate of all mortals. He died in the summer heat and sojourned a brief period in hell, returning again, after his mother’s pilgrimage, to renew life upon earth. In their kings they probably saw types of this dying god, men who by divine commission of the gods controlled the rains and winds, made the pastures grow and the flocks increase. This connection with nature was certainly attributed to the kings not only in ancient Sumer but to the kings of Babylonia and Assyria down to the Greek period. Mortal man appearing among men as a θεὸς σωτήρ, a divine savior, had naturally more affinity with the dying god than with any other deity. There is also little doubt but that prehistoric kings actually posed as the youthful son and beloved of mother earth, the virgin mother goddess, for a dynastic list of prehistoric kings in our collection actually names Tammuz as one of the ancient rulers of Erech. Probability rests with the thesis that the virgin mother goddess and her son and beloved consort who perishes annually arose originally as religious myths. These deities are primitive and older than the idea that royal rulers are patrons of earth’s productive powers, and sons of the mother goddess herself. At any rate several of the kings of the Isin dynasty (2358-2133) which succeeded that of Ur, all of whom were likewise deified, appear in one hymn of the Berlin collection identified with Tammuz. The reasons which brought about this remarkable period of god man worship in Sumer are undisputably clear. They identified their savior kings with the dying son of the weeping mother, and believed them the divine redeemers sent to restore a lost paradise.

Assyriologists are fortunate in their study of this phase of religion in that a large number of tablets containing Sumerian hymns and liturgies to these god men have survived. Three long hymns of the cult of Dungi, first of the god men, have been found in the Nippur Library.2 One of them begins as follows:

Who causest devastation to befall the foreign lands,

Who speakest fearful decrees

Whom Enlil¹ chose (?) as the everlasting shepherd of the Land.

Oh divine Dungi, king of Ur art thou.

Whither he turns his eyes he speaks words of assurance.

By the command of Ninlil² pious works in the universe he has established.”

And a later passage of this hymn compares him with the greatest of the gods:

He that tirelessly eradicates anarchy, art thou.

On the reed-flute I will set forth these matters.

The name of the god king transcends all,

(Like) the name of Enlil whose fixed decree is not transgressed,

(Like) the name of Sin³ who decreed the fate of the city, whose splendour is unsupportable.

(Like) the name of Babbar4 attendant of the gods.”

In the liturgies to the real gods the singers often represent a god or goddess speaking to the congregation. So also in a liturgy to this immortalized king he stands forth proclaiming on the lips of the psalmists:

In wisdom verily have I been adorned.

By a faithful command may I be directed.

Justice may I love.

Wickedness may I not love.

I am Dungi, the divine, a king that is mighty, a man that excels all.

My name unto far away days be proclaimed.

My glory in Sumer be rehearsed.

In my city may my constructions be established.

The land of the dark headed people as one that tends his sheep may I behold gladly.

The kids may leap in peace on the mountains.”

Here we have in the public song services of the cult of the very first god man complete acceptance of the idea that “Divinity appeared living among them.” A Messiah had come and he had restored Paradise, which had been ended by the Flood. In fact this same liturgy refers to the Flood and tells how Dungi had come to banish the age of woe which had endured since the bliss of mankind had been ended by that disaster. The Dungi liturgy near the end has the following passage:

The raging storm wind uttered its roar with terror.

The devastating storm with its seven winds caused the heavens to moan.

The violent storm caused the earth to quake.

The rain god in the vast heavens shrieked.

And there were little hailstones and great hailstones.

But now the brick walls of the Temple of the Seal shine with splendour.

A king am I the storm winds [are silenced.]”7

In these liturgies which proclaim the arrival of the Messianic Age we hear little of the hope that at last mortality had disappeared. In that period a personal name “Dungi is the plant of life ” has been found in the inscriptions; perhaps there was a nascent hope that these saviors had actually banished mortality and death. But men still died and at last the god man died also. The death of the king was easily explained. He, like Tammuz, had gone to rest awhile in the shadowy world, or he had been received among the gods and ruled in one of the stars. Bur-Sin, successor of Dungi, was identified with Jupiter.

But men still died and this they probably explained by the belief that the Messianic Age had not been fully attained.

I venture to think that these liturgies were not sung in the cults of deified emperors after they had passed away, although their worship was otherwise maintained. They do not read like public services vices which could be sung to any but a living king. They had not a mystical belief in his second coming, nor had they created a religion of redemption through divine suffering in a supreme sense. The very doctrine of the divinity of kings effectively prevented the final evolution of a great spiritual religion like Christianity. For there we have a messiah whose chief attribute is temporal power, a god man who came, lived and departed amid the blessings of the gods. And this temporal power and divine prerogative passed to his son who at once became the subject of a new cult. This was fatal to a long continued belief in a departed god man. As a matter of fact Dungi, like all other deified kings, never secured a permanent place in the pantheon. The chronicles of later ages in recording his reign admit his title as god but for them he is only a man. When his line perished and his dynasty passed all traces of his cult disappear.

The two successors of Dungi, Bur-Sin and Gimil-Sin, received full cult worship; temples were erected to them throughout the empire though their reigns were brief. We possess no liturgies of their worship, but in our collection has been discovered a fine large tablet, a liturgy addressed to Ninurash, god of war, to celebrate the elevation of Gimil-Sin as prince regent during the life of his father.8 Ibi-Sin, last of the kings of Nippur, reigned 25 years and although he too was canonised and revered as a god man, yet he suffered the humiliation of captivity at the hands of the Elamites. A lamentation on this event has been found on a tablet of our collection in Constantinople.9 Thus the four demigods of Ur failed even to secure the perpetuation of their temporal power. An usurper from the land of Maer, Ishbi-Girra, claims to have seized the hegemony of Sumer and he founded in 2358 the famous dynasty of Isin which endured to the times of Abraham and Amraphel and counted sixteen kings, all of whom received divine honors. Faith in these mortal saviors had not waned, but, as we see, flourished to the end of the last Sumerian dynasty. And it did not yield to a new religious faith as Roman Emperor worship yielded to Christianity, but this cult passed away because the Sumerians themselves became extinct. The Semitic conquerors who partially adopted this belief in the age of Sargon, rejected it in the age of Hammurapi, or at any rate rejected the cult worship of kings. Belief in their divine rights as sovereigns persisted, and an intimate connection between them and nature was held to exist to the days of Nebuchadnezzar. The rulers of Isin appear to have been Semites themselves, but the literature, religion and culture of their reign are thoroughly Sumerian. If god man worship continued here, even in more emphasized manner, it must be attributed to popular belief. The Semites of the Babylonian dynasty, whose state was also Semitic, probably eliminated this cult because they rejected the idea of a man god and also the idea of a restored Paradise. At any rate their poets constructed a great epic in twelve books, known as the Epic of Gilgamish, and the thesis of this work is that man shall never escape the limits of mortality.

Our Nippur Collection seems to have been largely composed during the reign of these Isin kings, I mean the important literary documents of the Museum. During this period the fine and intricate Sumerian liturgies were written, which became the accepted prayer books of Assyria and Babylonia. Many beautiful hymns and liturgies of the royal cults of the Isin kings belong to the Nippur Collection. From these we learn that the canonized rulers were actually identified with the dying god and lover of the mother goddess. A fine Sumerian hymn of seventy-seven lines celebrates the betrothal of Idin-Dagan, third king of Isin, with Ninsianna, the great earth mother goddess, and queen of heaven.10 The fourth king Ishme-Dagan, who ruled twenty years, has left the impression of his personality upon the literature of his period more than any other sovereign of that age. Two fine hymns of his cult have been recently published and translated.11 Of him the psalmists of his cult sang:

He the judge, giver of decision, who directs the land,12

Who makes justice exceeding good.

The transgressor he pardons, the wicked he destroys.

To justify brother with brother to the father he………

Not to justify the slander of a sister against the elder brother to a mother courage he ensures.

Not to place the weak at the disposal of the strong………

That the rich man may not do whatsoever is in his heart, that one

man to another do not anything disgraceful,

Wickedness and hostility he destroyed, justice he instituted.

May the sun god, son whom Ningal13 bore, my portion fix.

He whom Innini,14 queen of heaven and earth,

As her beloved spouse has chosen, I am.”

A liturgy consisting of two long melodies glorifies him as the patron of nature. Enlil proclaimed that in his reign:—

In the cellars of the gardens the honey shall reach the edges.”

The Berlin Collection contains the twelfth melody in 38 lines of a liturgy sung in his cult.15

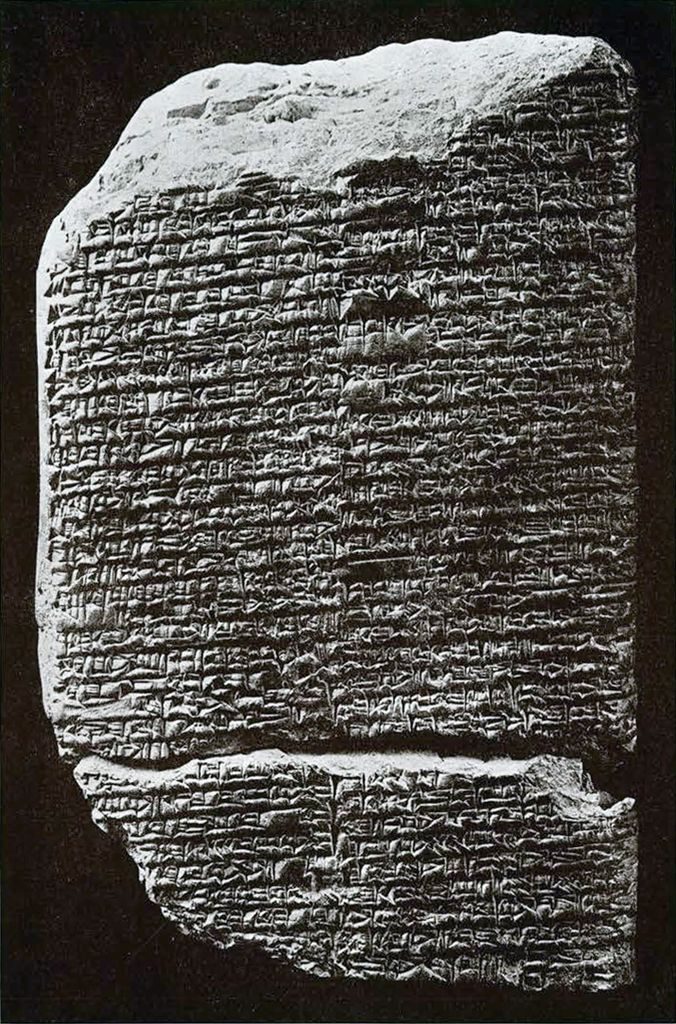

The fine double column tablet photographed with this essay contains a liturgy in six melodies of the cult of Ishme-Dagan. A few lines have been broken from the top but the greater portion of the 160 lines of this song service are preserved. This composition is an important addition to religious literature and unique among all the choral compositions of antiquity. Here the divine ruler actually appears in a character closely resembling that of the great mater dolorosa in the liturgies to the gods themselves. Briefly, the position of the unmarried mother goddess in the long daily liturgies of the temples of the ordinary cults was this. She occupies a position in relation to mankind sharply distinct from all the other great deities. The standard liturgies mournfully rehearse the tribulations of mankind, the glory and power of the great gods, and attribute all human woes to their wrath caused by the sin of men. But the virgin mother in melody upon melody is represented as a weeping mother of mankind, wailing with them before the angry gods. She is the great earth spirit from whom sprang mankind and all living things. Their sorrows are her sorrows. And, like Tammuz, her child, she is responsive to human fortunes. Therefore, the connection between the deified kings and the weeping mother goddess was apparent. He also shares their joys and sorrows, a divine man begotten of a great god and born of the mater dolorosa herself, to live among men as men live, to acquaint them with incarnate and tangible deity.

The newly deciphered tablet No. 13856 contains a liturgy to Ishme-Dagan modeled after the standard liturgies of the great gods, more particularly after the weeping mother song services in which the mother goddess Innini under various titles wails with her people.16 All other public song services, hitherto recovered from the rituals of the cults of deified kings, consist in panegyrics on the divine character of the cult hero. But here the theologians have ventured into the extremity and have constructed a liturgy similar to the weeping mother services replacing the mater dolorsa by the man god. In their religious beliefs he was her son and beloved consort, and our new document confirms the conclusion that these heroes occupied in the minds of the believers a position of power over nature and of susceptibility to human experience equal to that of Innini herself.

The first melody contains about 50 lines and began by relating how Enlil had ordered the glory of Nippur, and then having become angered against his city he sent desolation upon her at the hands of an invader.

The people, the dark headed, he caused to have reverence.17

But her habitations he cursed

Like scattered cows he scattered them.

In the city whose interior is filled with weeping,

While the consort, its divine queen is not solicitous for her,

The great house which knew the cry of multitudes,

Like a vast building in ruins men enter not.

In Nippur where great princes were prosperous, why have they fled?

The people, the dark headed, all of them like sheep are fled (?)

How long shall loud crying, weeping and wailing distress the heart

How long shall souls be terrified

And hearts repose not?

To the drum and loud tambourine will I sing.”

This selection from the first melody affords an excellent sample of the first song of most of the daily liturgies. These melodies arranged to follow each other, often to the number of twenty or thirty in one liturgy, originally referred to a real historical event, and such lamentations were incorporated into the standard breviaries and sung for ages as expressions of human sorrow long after the calamity itself had been forgotten. This melody which inaugurates the liturgy of Ishme-Dagan is probably borrowed from an ancient lamentation.

In the second melody of about thirty lines the divine savior king appears lamenting for human sorrows.

Maid and young man and their children cruelly have been scattered afar, tearfully I sigh.

Their brothers are fled afar (like those driven) by a storm wind. The household like a cow, whose calf has been separated from her, stand by themselves with sorrowful souls.

They have lapsed into the misery of silence.

Oh sing to the lyre; the wailers like a child nursing mother, who cries in woe, because of them devise lamentation.”

Between the second and third melody is a single line of antiphon probably sung by a priest while the musicians prepare for a new score.

In the third melody the psalmists reflect upon the injustice of the city’s fate and look for a time when Enlil will be reconciled. The song is of course only a reflection upon an historical event applied implicitly to universal affliction.

Until when shall it not return to its rest? Until when shall its ‘How

long?’ not be spoken?

Why are its brick-walls trodden under foot,

And the doves screaming fly from their nests?

. . . . . . . .

Bitter lamentation I utter, tears I pour out.

Oh sing to the lyre, he that speaks the song of wailing.

The hearts which are not glad it will pacify.

The decrees of their lord they have glorified.

He18 concerns himself not with their oracles, he cares not for their destiny.”

Here ends the third melody and a two line antiphon separates it from the fourth.

He has concerned himself not with their oracles; he cares not for their destiny.”

In the fourth song the choir again represent the god Ishme-Dagan sorrowing with his people.

Sound of mourning he causes to arise, lamentation he utters.

Now oh sing to the lyre, they that know the melodies.

Now I am filled with sighing.19

Her population offer prayers to me.

Now my intercession, my pleading20

Even now mightily the population unite with me in making known (to the gods).

Upon ways of pain my mercy,

Oh woe, my children weep for.

In the house, the well built temple, in their dwelling,

Sound like one chanting is raised and praise is diminished.”

The fifth melody ends with a passage representing Ishme-Dagan interceding with the earth god.

Thy head which is held aloof turn unto me to glorify thy portion. The hostile deeds which he did unto thee be returned upon his head. In the city which knew not forgiveness let there be given the cry of multitudes.”

The last sixth and final song promises the end of Nippur’s sorrow. Enlil has ordered the restoration of peace and has sent his beloved shepherd Ishme-Dagan to bring joy to the people.

Unto the brick walls where lamentation arose he will command ‘it

is enough.’

Thy happy soul he will cause to return for me.

Ninurash the valiant guardsman will sustain thy head.

His pastor he will establish over the city.”

These selections will give an idea of the general character and trend of ideas developed in this remarkable cult document. The reader must not infer that the doleful reflections of the choir and their fanciful figure of the divine ruler weeping for a destroyed Nippur actually refer to a state of affairs when the liturgy was sung in the cult of this king. Nippur is only taken as a concrete example of universal sorrow. This song service has a more universal application and a deeper meaning. It describes the miseries of life and the solicitude of the man savior, he who intercedes against the wrath of god aroused by sin. We may, therefore, be modest in claiming for our new tablet a place of peculiar importance in cuneiform literature. The large number of song services of these cults now recovered in our Museum emphasizes once more the supreme fact in the religious beliefs and moral conduct of humanity. To be effective a great religion at one time or another is bound to find “divinity appearing alive among them.” The divine and moral measure of this personality has largely determined the character and the success of all great religions.21

S.L.

1 This date is in dispute. Some place this king as late as 2650 and others as early as 3800.

2 One now in the Library of the University of Dublin was obtained from a dealer. This tablet was obviously filched by Arabs from the Expedition of our University. Published in the writer’s Sumerian Liturgical Texts, pp. I 36-140. A liturgical hymn, of which two duplicates have survived, was published by the writer in his Historical and Religious Texts, 14-18. Also a hymn to Dungi before he was deified, ibid., 9-13. The second tablet of a liturgy in the cult of Dungi was published by HUGO RADAU in his Miscellaneous Sumerian Texts No. 1, Hilprecht Anniversary Volume.

3 The earth god.

4 Consort of the earth god.

5 The moon god, patron deity of Ur of the Chaldees.

6 The sun god.

7 This important passage occurs in Historical and Religious Texts, page 17 ,Reverse, Cal. I,lines 9-16. It proves that the deified kings were actually supposed to have inaugurated the Messianic Age. The Epic of Paradise, which also belongs to the Nippur Collection, is thus confirmed by the ideas set forth in this Dungi liturgy. The Flood, according to the epic, was sent by the angered creator of men to end the blissful age. And in our hymn to this divine savior we find him praised as the deliverer who now reclaims mankind from the evil age. The word employed in this liturgy for Flood, marur, translated into Semitic by abubu is the prototype of the word mabbûl, employed in Hebrew for the Flood. Abubu is also the word ordinarily employed in cuneiform literature for the Deluge or Flood.

8 Published by HUGO RADAU, Babylonian Expedition, Vol. 29, No. I.

9 Published in Historical and Religious Texts, pages 5-8. A hymn of Ishbi-Girra, founder of the Isin dynasty which succeeded Ur in the hegemony of Sumer, says that Enlil became angered against Ur and caused Ishbi-Girra, a man of Maer, to seize the foundation of Ur. No. 7772, unpublished. The Nippur Collection possesses three fragmentary hymns sung in the cult of Ibi-Sin, No. 8310; 8526; 13857, all unpublished.

10 Published and translated by HUGO RADAU Sumerian Miscellaneous Texts No 2, and also edited by the writer in his Sumerian Grammar, 196-200. Visitors will find this tablet exhibited in Case 21 of the Babylonian Room, in the University Museum.

11 In the writer’s Sumerian Liturgical Texts, 143-149 and 178-184.

12 The choir here return to the third person in speaking of Ishme-Dagan.

13 The wife of the moon god.

14 Chief title of the unmarried mother goddess, virgin mother of Tammuz and his lover.

15 HEINRICH ZIMMERN, Sumerische Kultlieder our Altbabylonischer Zeit, No. 200.

16 ‘The limitations placed upon this popular exposition excludes a detailed discussionof the standard Sumerian prayer books used in public services. For an investigation in their principles see the writer’s Babylonian Liturgies (Introduction).

17 Nippur excavated by the Museum’s Expedition was regarded by the entire Sumerian race with peculiar reverence.

18 The pronoun refers to Enlil.

19 Liturgies pass from first to third or second persons and vice versa promiscuously and unexpectedly/

20 Here the divine savior intercedes for mankind with the great gods.

21 The reader may wish to know the extent of the hymns and liturgies now recovered from the cults of the remaining kings of Isin. Libit-Ishtar, the fifth king, is the subject of a fine song service in four melodies published by ZIMMERN in his Kultlieder No. 199. A fragment of a hymn to Enlibani, eleventh king of the dynasty, belongs to the Nippur Collection in Constantinople and is published as No. 38 in the writer’s Historical and Religious Texts. A fragment containing the opening lines of a fine hymn has been published in the writer’s Sumerian Liturgical Texts, 140-2; the king in question is uncertain. Probably Libit-Ishtar.