The Museum has had the good fortune to secure a very interesting loan of three Greek vases, all in good condition, and each typical of the period in which it was made. These vases are the property of Mrs. John Kearsley Mitchell, and were acquired by her father-in-law, the late Dr. S. Weir Mitchell.

Image Number: 3424

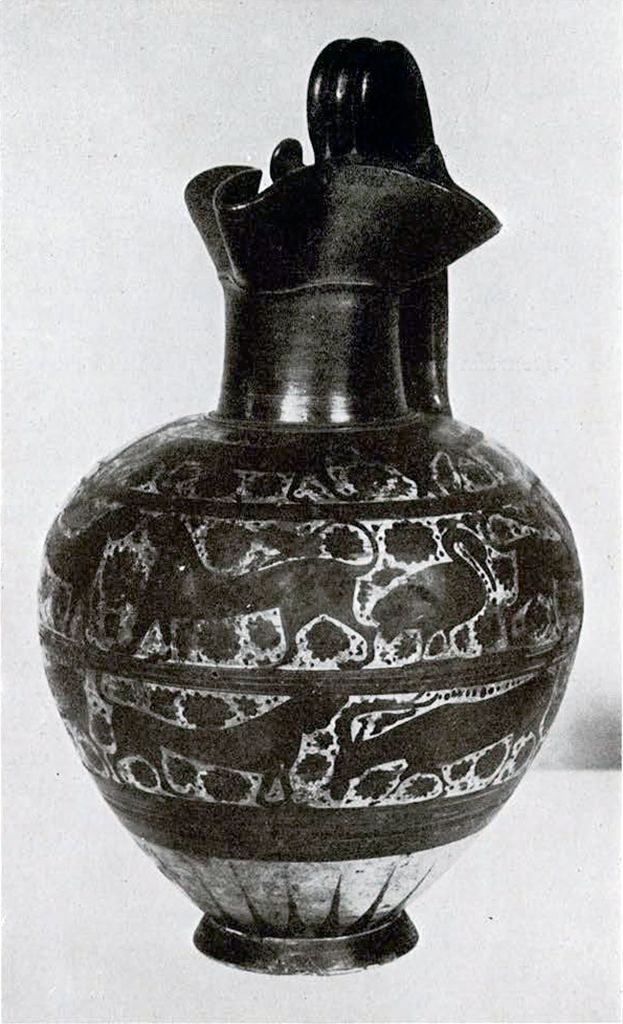

The earliest of these vases is an œnochoe, or pitcher, made, either in Corinth, or by Corinthian colonists in Italy (Fig. 72). The decoration of the body is characteristic of the Corinthian technique, and shows its “Orientalizing” tendency, the result of the great trade relations existing between Corinth and Asia Minor. It is divided into three bands, or zones, in each of which is a row of animals. The upper band consists of a ram, a lion and a goat; the middle, of four lions, a ram, a swan and a goat; the lower, of three lions and three goats. With a “horror vacui” typical of these “Orientalizing” vases, the field is sprinkled with a profusion of dots and rosettes. Details are rendered by an abundant use of incised lines. The neck and trefoil mouth are plain. At the foot are rays of black on a light ground.

It is hard to determine whether this vase was made in Corinth itself or whether it is “Italo-Corinthian.” But it seems to me probable that this œnochoe is a true Corinthian specimen. It is fortunate that there is in the possession of the Museum a good collection of Corinthian and Italo-Corinthian vases, with which it is possible to compare this vase. By looking at a pair of pitchers of Corinthian technique already in the Museum (No. 31, in Case XII of the room to the left of the staircase) it was found that the specimen loaned by Mrs. Mitchell corresponded with them in almost every detail, except that it is smaller, and is undecorated on the neck and lip, while the specimens owned by the Museum have these parts ornamented with rosettes in white.

The preservation of this œnochoe is excellent; although it has been mended in many places, most of the vase is still there. It was made in the late seventh or early sixth century B.C.

Image Number: 2823

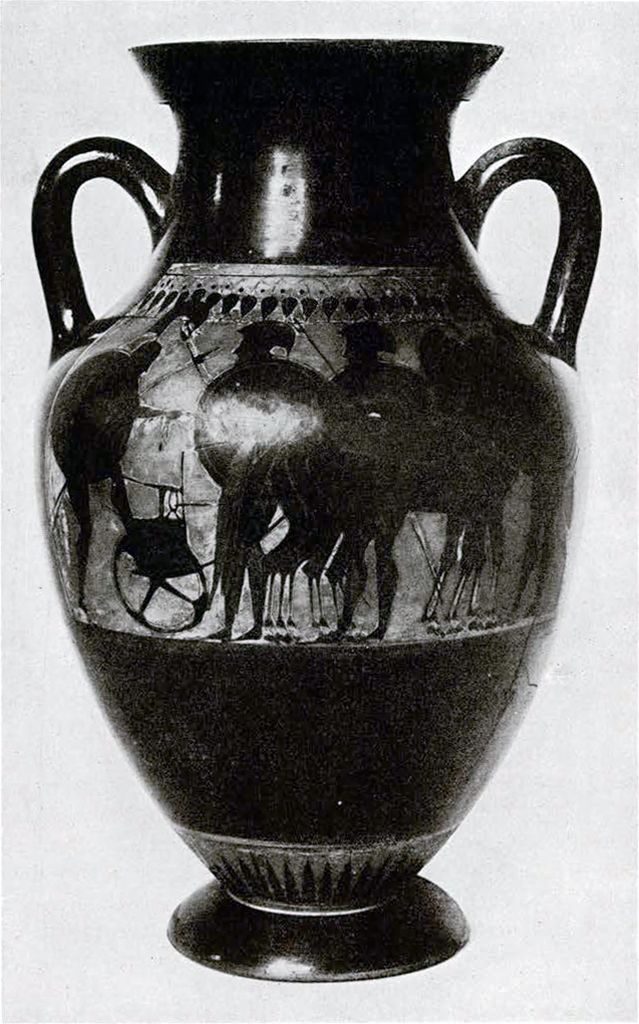

The second of these vases is an Attic black-figured panel-amphora, so called because the designs are drawn in black in panels left in the color of the clay, while the rest of the vase is covered with black varnish. This vase is in every respect the finest of the three loaned, and in the brilliancy of its glaze and its perfect preservation is not only unsurpassed by any specimen already in the Museum, but is the finest specimen in Philadelphia known to me. It was made early in the best period of the Attic black-figured technique, about 530-525 B.C.

Side A, or the obverse (Fig. 73), has as its design a warrior, facing to the right, wearing a helmet with a high crest, a cuirass, under which is a short chiton, or undershirt, and greaves, and carrying a round shield on his left arm, and two spears in his left hand. He is mounting a light four horse chariot, or quadriga, and holds the reins in his right hand. Beside the chariot are three other warriors facing him, on foot, similarly armed. At the top of the panel is a band of lotus buds.

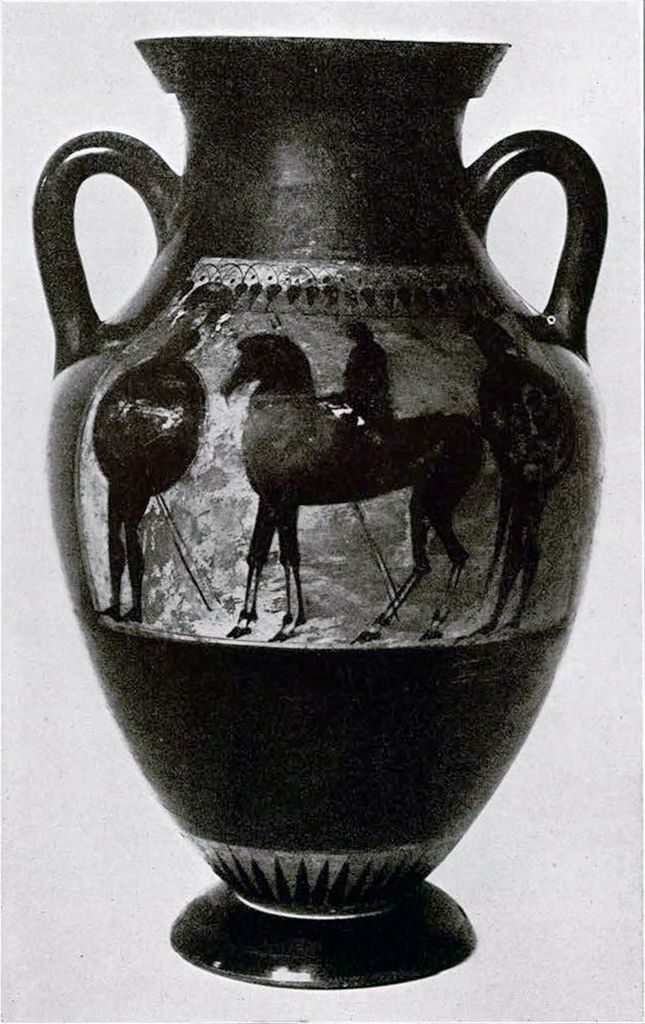

On Side B, the reverse (Fig. 74), a horseman is seen, facing the left. He is bareheaded, and wears a cloak, called a chlamys, and carries two long spears in his left hand. By accident the vase painter has given the horse two of each leg, or eight legs in all. This is a not uncommon mistake. Details of the drapery of the rider are given in white overcolor, most of which has worn away. On either side of the horseman is a warrior, armed as on Side A. Originally, their round shields were decorated with devices in white overcolor, most of which has gone. Above, as on Side A, is a band of lotus buds.

Besides the white overcolor we find red used on Side A for the manes and tails of the horses, and the greaves of the warriors, while there are also traces of white in the legs of one of the horses. Details of drapery and anatomy are in all cases rendered by a very copious use of incised line drawing, done with painstaking accuracy and skill. The base has a ray pattern in black on the color of the clay.

Image Number: 2824

There are several indications that tend to put this vase in the beginning of the best black-figured period, or in the neighborhood of 530 B.C. They are minor details; the stiffness and archaic quality of the drawing in this case is not such a good criterion, as this stiffness is to a certain extent characteristic of the entire black-figured technique. I will mention, however, two of these points, that prove the vase to be of early date. The first is the absence of palmettes, and the presence of lotus alone at the top of the panel. The palmette later becomes almost inevitable on all vases; but the use of the lotus antedates the palmette. It is true that this lotus chain found on this amphora is found on red-figured vases by Euthymides in the fifth century; but it is always in conjunction with palmette ornaments as well. It is the absence of the palmette that is significant.

The second point lies in the handles. The later panel amphorae nearly all have flanged handles. The round handles on this vase, coupled with the absence of palmette decoration, point to the early date in the black-figured technique assigned to this specimen.

The third vase takes us away from Greece, and brings us down a little over a century later. At this time, when the Peloponnesian War was raging, and when Athens went down to defeat in the Sicilian Expedition, she lost more than her military prestige and political supremacy; her commercial predominance in the ancient world departed as well. During the fifth century the Athenian potters and vase painters had driven all others out of competition. Attic vases were exported all over the ancient world, and were prized by lovers of the beautiful in Italy, in Asia Minor, in the Islands, and even in the Crimea, as the excavations show us. When, therefore, the Peloponnesian War broke out, and the supply of Attic vases was automatically diminished, if not altogether stopped, it was natural that wares in imitation of Attic should arise.

Image Number: 3106

This is true especially in Southern Italy, among the Greek colonists there. Three or four styles can be distinguished one from the other, of these imitative wares. They take their names from the localities in which they are found, and are (1) the so-called “School of Paestum;” (2) the Lucanian; (3) the Campanian; (4) the Apulian. It is to this last class that our third specimen belongs.

A few words about the Apulian ware may not be out of place before passing to the formal description of this vase. It is the largest class in point of the area covered, and the most numerous in point of specimens found, of any of the South Italian techniques. Every shape of vase known to the Attic potter was made by the Apulians; and certain forms, like the enormous kraters, or mixing-bowls, with volute or medallion handles, so common in the Musee Nazionale at Naples,1 they may be said to have developed and made their own. At first they imitated quite closely the vase painters of Attica; later, however, they developed a peculiar style, that is almost unmistakable, and finally they degenerated to a very poor, florid, decorative manner. The places where Apulian vases have been most commonly found are the following ancient sites: Tarentum (the modern Taranto); Canusium (the modern Canosa di Puglia); and especially Rubii (the modern Ruvo di Puglia). The best collections are in Italy, in the museums of Naples, Taranto, and Bari, and the Jatta Collection at Ruvo.

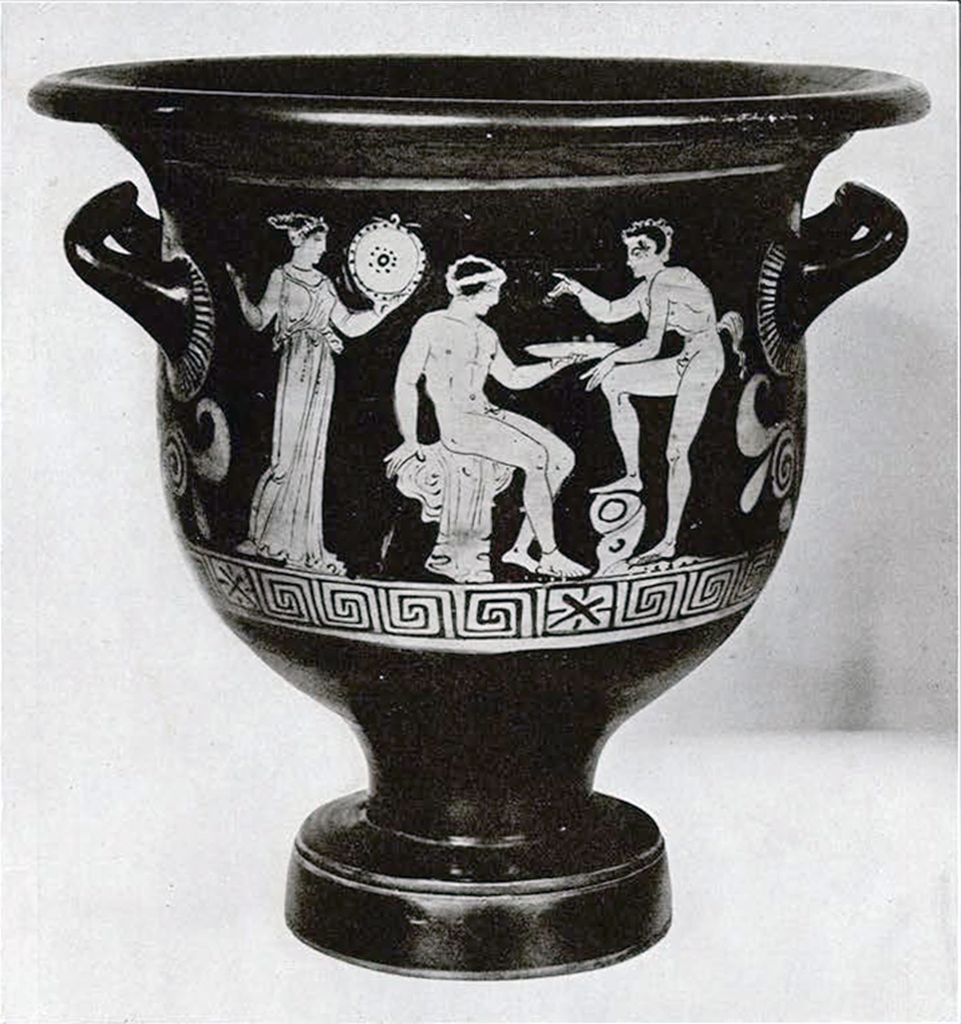

The vase under discussion is a good example of the Apulian style, as it was on the point of departing from the Attic models, and developing its own peculiar features. Its relatively early date (ca. B.C. 400) is proved by the absence of overcolor. On a later specimen, e.g., in the exhibition room to the left of the staircase, No. 94 in Case XIII, the woman on Side A would be done in white. More emphasis would be laid in a later specimen on the dots under the feet of the seated youth, to represent the ground, a trick peculiar to the Apulian technique. Otherwise, the drawing of the vase, in its freedom of execution, and the type of design, shows what might be called the typical early Apulian mariner, free from most of the Atticism of the earlier, or “Atticizing” period.

Image Number: 3109

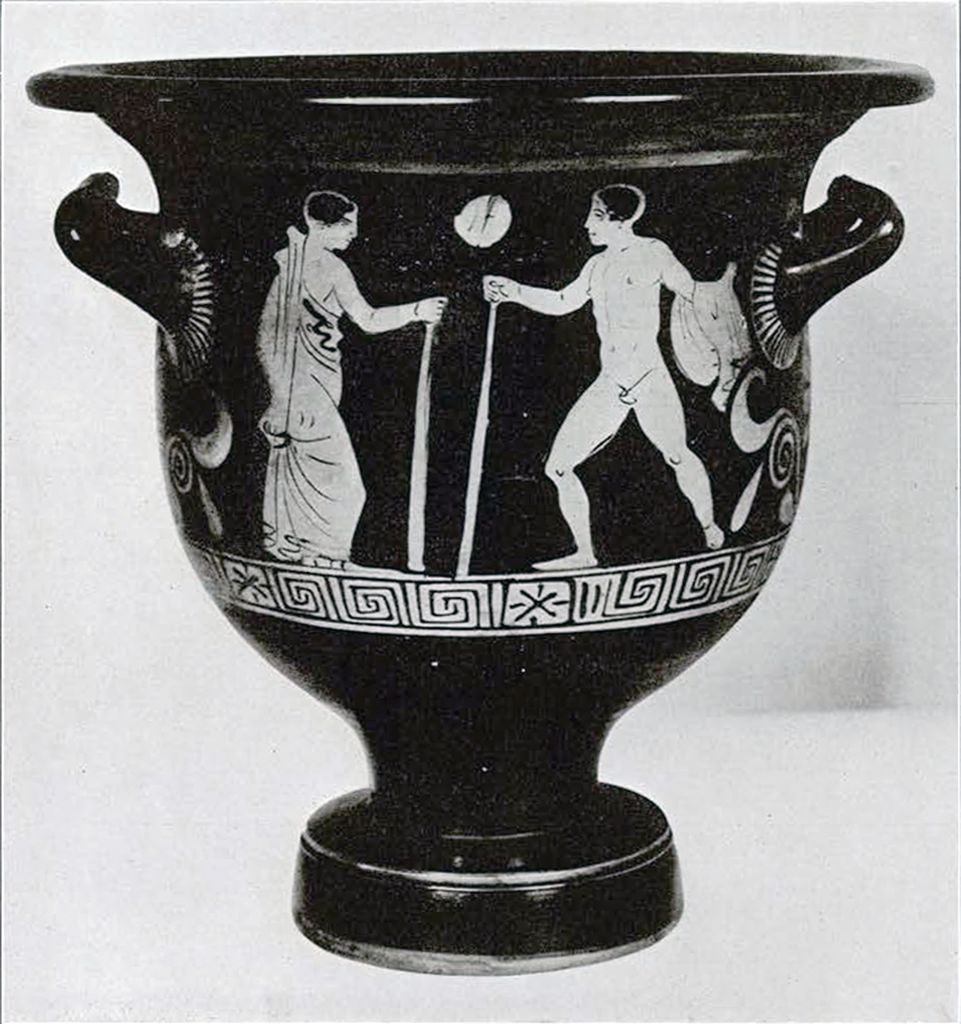

In shape it is what is called a bell krater, from the bell-like form. The handles are placed near the lip. This shape was invented in Athens in the fifth century B. C., in the period of the Attic red-figured technique. No black-figured vases of this shape are known to me. In this specimen, as in the Apulian vases generally, the red-figured technique is employed.2 Around the lip, a wreath of laurel is painted; under the handles are large palmettes; and below the principal designs, a meander pattern.

The principal design (Fig. 75), has as its central figure a seated youth, facing the right. He is nude, and sits on his garments. In his left hand he holds a large bowl or basin, of a kind of which many examples have been found. Facing him is a nude youthful Satyr, gesticulating with his hands, with his right foot resting on a rock, so that the leg is bent. Behind the youth is a woman, dressed in a long chiton bound around the waist by a girdle, to leave a fold, known as a kolpos, just above the girdle. In her left hand she holds a large round object which seems to be a tambourine, as her right hand is drawn back to strike it. This woman is a typically Apulian figure.

The reverse (Fig. 76) has two youths meeting each other. The one at the left is standing still; he is draped in a himation, and carries a staff. The one at the right moves towards him. He is nude, and carries his himation on his left arm. He has a staff in his right hand. Between them, in the field, is a round, disc-like object.

It is a pity that no information is available as to the finding place of these vases, as they would thereby gain in archaeological interest; but artistically they are very fine, and the Museum is very grateful to Mrs. Mitchell for depositing them in its care.

S.B.L.

1 A good example of this kind of vase, perhaps the best in America, is on exhibition in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. ↩

2 A few small Apulian vases, mostly lekythoi, or oil-jugs, with black figures, are known, but they are rather rare, and are not pleasing in an artistic sense. There are three of these lekythoi at Memorial Hall, Philadelphia. ↩