Temple Bar

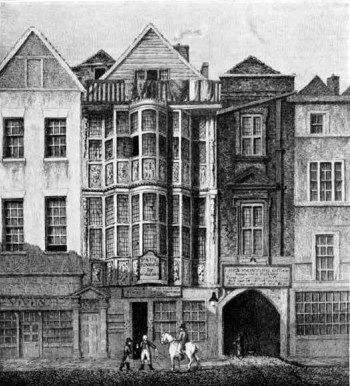

Adjacent to the Temple in Fleet Street and sharing its traditions are or were many ancient landmarks with memories preserved in literature and history, in song and in legend. Conspicuous among these landmarks was Temple Bar, a barrier or gateway extending across Fleet Street, a little to the west of the archway leading to the Middle Temple. Temple Bar was not a part of the main defences of the City—not a part of the continuous wall pierced by seven gates. It was a detached gateway in an advanced position toward the west on the boundary line between the City and Westminster, for it should be remembered that the wall itself was not the boundary of the City but a line running parallel to the wall and enclosing a narrow belt outside the wall. Some of the wards lie outside the wall. This explains such surviving names as that of Farringdon Without and Farringdon Within, two distinct wards; also Bishopsgate Without and Bishopsgate Within, two parts of one ward. Where the main roads crossed the boundaries of this outer zone as they approached the City gates, they were interrupted by bars for additional protection. Of these the one that survived longest was Temple Bar. Old Temple Bar, of unknown antiquity, was destroyed shortly after the great fire of 1666 and was replaced by another designed by Sir Christopher Wren, a fine arched gateway that was still in perfect repair in 1878, when it was removed to accommodate the increasing traffic. Temple Bar is represented today by a monument in the middle of Fleet Street, surmounted by the figure of a griffin, the Crest of the City.

Image Number: 22666

Fleet Street is in many respects the most important and the most famous street in London. It takes its name from the River Fleet that ran outside the western wall past Ludgate, where it was spanned by a bridge to carry Fleet Street to the gate. On the south side of the street, and without the wall, stood the Royal Palace or Manor of Bridewell, where Henry VIII lived at times, where Wolsey had a suite of apartments and where the whole of the third act of Shakespeare’s King Henry VIII took place. This spacious palace had frontages on the Thames and on the River Fleet. It was given to the City by Edward VI as a hospital and asylum for the poor. Later it was converted into a house of correction and lunatic asylum which it remained up to the time when it was demolished in 1863.1 Its site today is a maze of streets and buildings with shops and offices, among which is embedded the Church of St. Bride. Next to Bride-well, which took its name from the ancient well of Saint Bride—lying between it and the Temple—was Whitefriars. The Royal Palace and the seat of the Carmelite Brothers lay therefore between Ludgate and the Temple, and between Fleet Street and the Thames. Lying outside the wall but inside the City, they had Temple Bar as an outer protection. Temple Bar is at least as old as the Temple whence it derived the name by which it has been known to history. From time immemorial the spot has been marked by some kind of a barrier; at first, as has been surmised, nothing more than an iron chain.

Image Number: 203622

Ludgate being the principal gate of the City looking west and the outlet toward Westminster and having in its vicinity the Royal Manor of Bridewell, its approach was of special consequence and Temple Bar has witnessed and continues to witness many impressive ceremonies attended by great pomp and splendour. Its colourful fame rests substantially on the picturesque part it has played in relation to the Royal Processions in their entry into the City, for Temple Bar is the official entrance to London. There the Sovereign halts, members of the Royal household on the King’s business halt and troops marching with fixed bayonets halt to remove them, for troops do not pass through the City streets with fixed bayonets though they go with fixed bayonets everywhere else.

In accordance with that ancient custom that requires the Sovereign on his way to visit the City to knock and ask leave to enter, a ceremony is performed at Temple Bar on these State occasions with all the stately pageantry that Royalty on the one hand and the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London on the other can command. We have an account of the entrance of Queen Elizabeth when she went to Saint Paul’s to give thanks after the defeat of the Armada. At the accession of James I a great triumphal arch, a magnificent affair described as a Temple of Jauns, 90 feet high and 50 feet broad was erected beside the Bar to give greater dignity to the entrance of London. It was provided with battlements and turrets. It had a great gate in the middle. It was adorned with allegories and within was delivered an oration prepared by Ben Jonson. From contemporary descriptions it would appear to have been an affair of extraordinary grandeur even for the London of that day.

Coming down to a later day, Queen Victoria on her Diamond Jubilee procession was received by the Lord Mayor at Temple Bar with all the accustomed ceremony. At each of these Royal entrances the Lord Mayor presents the Sword of London to the Sovereign who immediately returns it.

When a Court official on the King’s business enters the City he likewise is halted at Temple Bar to receive the Lord Mayor’s permission. The most recent observance of this timehonoured custom was in July 1919 when the King’s Herald rode into the City from Saint James’s Palace to read from the steps of the Royal Exchange the King’s Peace Proclamation on the day that the German delegates signed the Treaty of Peace in Paris.

But Temple Bar has memories of another kind. Like the gate of London Bridge it was adorned at times with the heads of traitors fastened on spikes that were prominently placed on the pediment above the central arch. Among the heads thus exhibited was that of Henry Oxburg who took part in the uprising of 1715 under the Old Pretender. A contemporary writer thus describes the placing of the head.

On the evening of the execution a man was seen with a small bundle under his arm ascending a ladder to the top of Temple Bar. Arrived there he took the white cloth off that which he carried in it and then the men and boys gathered below saw that it was a human head. The man thrust it on to an upright iron rod, then descended to the cart which awaited him and drove away towards Newgate. Next day idlers were peering at the head through a glass and pious people crossed themselves.

But one of the pious people was a Jacobite who, enraged at what he saw cried out “God damn the people who put that head up there,” and proceeded to involve himself in a small riot. If it was his purpose to have his own head placed on the gate he was disappointed. He only got a month for making a disturbance.

Another head that adhered to the Old Pretender’s cause adhered to Temple Bar for thirty years, a record. It was finally blown down one night during a gale and was picked up by an attorney who showed it to some friends in a public house near by. Dr. Rawlinson, the archeologist, according to a story, hearing what had happened, wished to purchase the head and to accommodate him someone sold him another which he carefully preserved.

Image Number: 171565

The last heads exhibited on Temple Bar were those of persons condemned for their part in the rising of 1745 under the Young Pretender. It was in 1746 that the last of these, Townely and Fletcher, were executed, when their heads completed the ghastly toll. Horace Walpole, writing the same year says, “I have been this morning at the Tower and passed under the new heads at Temple Bar where people made a trade of letting spying glasses at a halfpenny a look.” Twenty seven years later, in 1773, Dr. Johnson told a story often repeated of the same heads at a dinner of the Literary Club. It appears that the two heads remained together until March 31, 1772, when one of them was reported to have fallen down. Temple Bar itself remained for 106 years longer, till 1878, when it was removed stone by stone and reërected at the entrance of Theobalds Park, Cheshunt, where it may still be seen. There is some talk of having it brought back to the City and set up anew on the Thames Embankment.

On the south side of the street at Temple Bar, with which it formerly communicated, is Childs Bank, the oldest bank in London, rebuilt in 1878. This is the bank described by Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities under the name of Tellson’s. Next door to Childs stood the Devil Tavern an ancient and celebrated tavern and the favourite haunt of Ben Jonson, who there presided over the Apollo Club. In 1687 the Devil was bought by Childs and replaced by an extension of the bank. In Childs Bank may still be seen the old sign of the Devil Tavern, Saint Dunstan in company with the Devil. In the same place is preserved a bust of Apollo and a tablet taken from the room in which the Apollo Club used to meet. In gold letters on that tablet you may read the rules composed by Ben Jonson for his club.

Another famous house in Fleet Street was the Mitre Tavern—one of Samuel Johnson’s resorts. It stood where Hoare’s Bank now stands and the Mitre Tavern in Mitre Court nearby is a modern establishment. The Rainbow, one of the first coffee houses in London was opened in 1656 by James Farr, sometime a barber. He was prosecuted “for making and selling a sort of liquor called coffee as a great nuisance and prejudice to the neighbourhood.” Nevertheless the Rainbow prospered and though it has been remodeled is still one of the attractions of the neighbourhood. Also close to Temple Bar on the north side of Fleet Street stood the famous Cock, where Samuel Pepys entertained two lady friends to a lobster supper and got in trouble with his wife as he relates in his diary. Tennyson’s Will Waterproof adds a later and better known lay to the literary traditions of the Old Cock. The gilded sign, carved by Grinling Gibbons, a fireplace and other features long remembered, form part of the decorations of the modern Cock Tavern on the other side of the street, erected when its predecessor was pulled down in 1886.

Dick’s Coffee house, reached by a narrow passage on the south side of Fleet Street near Temple Bar, adjoined the buildings of the Temple in Hare Court. It was a favourite resort of Steele and Addison as well as of many others whose names are known to fame, down to the year 1899 when it was demolished.

Image Number: 203626

All of the taverns I have mentioned and many more living in London’s memory with Temple Bar—all these ancient haunts of fellowship and freedom from care that ministered to the dwellers in the Temple and to travellers to and from the City, have been swept away within the last half century but linger still in the memories of living Londoners. One of the old taverns of the Temple neighbourhood remains unchanged, the Cheshire Cheese in Wine Office Court, Fleet Street. The present building dates from the seventeenth century. The tradition that Dr.Johnson at times frequented the Cheshire Cheese is denied by some, but I see no reason to doubt the innocent story. Certainly it was there in his time and I am sure he frequented every tavern in his kingdom.

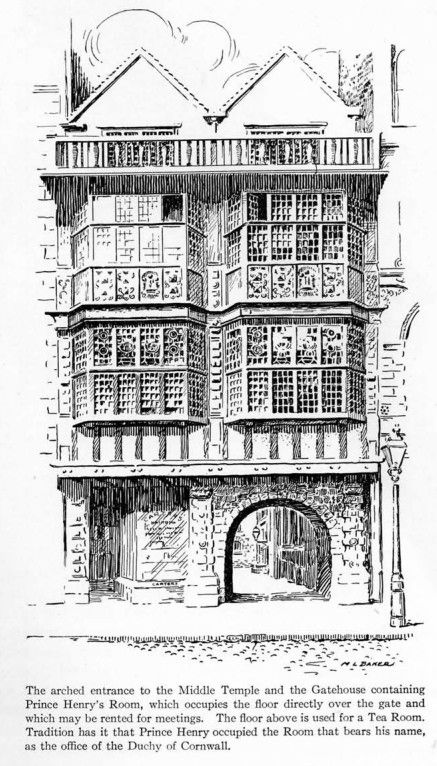

Opposite the end of Chancery Lane is the gate of the Inner Temple, with its gatehouse known as Prince Henry’s Room. It was built in 1610 and named in honour of Henry, Prince of Wales, the son of James I. Its most interesting feature is a large square room with fine carved oak panelling and pilasters and an ornamental plaster ceiling. It is one of the few private houses that the Corporation of the City of London together with the London County Council have decided to preserve.

Henry, Prince of Wales, is one of those bright attractive spirits that pass quickly across history’s stage and are gone. The eldest son of the first James, he showed all the qualities that a prince should have. He was handsome, eager in pursuit of knowledge, fond of learning, but also fond of games and outdoor life and manly sports. He was by nature generous and affectionate and was beloved by the Londoners. He was a great friend of Raleigh whom he constantly visited in the Tower. He died in St. James’s Palace in his 19th year. One cannot help wondering what the fortunes of the Stuart Dynasty might have been had it survived in the person of that most promising scion of the House.

Southwark Inns

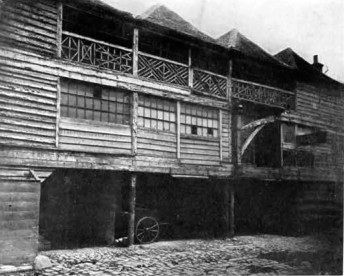

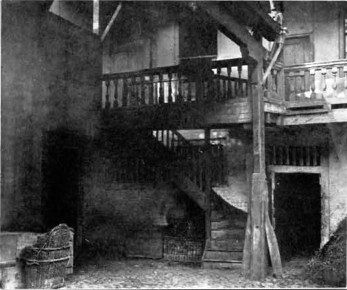

There are certain thoroughfares that lead one’s footsteps on amid a throng of ghosts by ways frequented since that far off London dawn that saw the first arrival on the Thames. As one travels these highways, memory threads the passages of time till step by step the journey leads through crowded centuries to dim horizons where spirits refuse to be summoned from the vasty deep. One of these thoroughfares is Fleet Street; another is that which begins at the southern end of London Bridge and runs through Southwark away toward the southeastern counties of England. It was the road that led from London to the coast before the Romans came and, connecting with the Continent, carried the rising tide of London’s foreign trade before Caesar sailed from Gaul. The Romans improved that Dover road and, where it approached the bridgehead, it became lined with houses that spread along the river and from the river into Surrey till the Roman City claimed the southern side of the Thames opposite the frowning bastions that guarded the stronghold on the northern bank, with which it was connected by the bridge. That was the beginning of Southwark. It was created by the most important approach of London, the road that led to the coast and the Continent and straightaway to Rome. Today that road is called Borough High Street and time has obliterated its monuments but not its memories. It has swept away the Roman Hippodrome and Shakespeare’s Theatre, the Globe. It has swept away Chaucer’s Inn and Jack Cade’s Inn but the road runs as it always ran adapting itself to all changes without ado. No other road to London brought so many travellers from all lands and no street in London had more famous inns. Thus Chaucer, who gives a picture of the jovial landlord as well as of the company that was setting out for Canterbury on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Thomas a Becket, London’s patron saint, a pilgrimage so popular that the Southwark inns did a profitable business with the pilgrims. Tabard Inn survived till 1876, when it was pulled down to make room for more modern uses. A hop merchant’s office and a modern inn called the Old Tabard now occupy the site.

The advent of the railroads and the dislocation of the old traffic caused the first general removal of old inns, but the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the present century witnessed the obliteration of many more.

Another historic inn on Borough High Street was the White Hart Inn, built in the fourteenth century. It was there that Jack Cade had his headquarters in 1450, when he attacked London, according to the chronicles and according to his own announcement in Shakespeare’s King Henry VI. Dickens gives a good description of the White Hart as it appeared in his day for it was there that he introduced Mr. Pickwick and Sam Weller to each other. It was pulled down in 1889.

The George Inn stood between the Tabard and the White Hart and a fragment of it is standing and entertaining travellers today. Next to the Tabard stood the Queen’s Head Inn, once owned by John Harvard, who inherited it from his mother and who, having emigrated to Massachusetts, endowed the College that bears his name. The Queen’s Head was removed in 1895.

Holborn Inns

Returning to the north of the Thames, Holborn ranks as one of the principal approaches to the City. Along that way Watling Street, the Roman road to the North, led into the City via Newgate. A pair of granite obelisks astride of Holborn, one at the end of Grays Inn Road and the other at Staple Inn opposite, mark the site of Holborn Bars the barrier that, like Temple Bar, stood where the road crossed the boundary of the City. High Holborn claims the distinction of being adorned still with one of the few surviving houses of Elizabethan times, Staple Inn with its picturesque halftimbered front of many gables, its fine old Hall, its two courts, its sunken garden and its soft repose. It was an Inn of Chancery and is one of the best surviving bits of 16th century architecture in London. High Holborn escaped the great fire and till the end of the nineteenth century retained some of the finest of the old inns. There was the Old Bell a famous inn of the galleried type like the inns of Southwark, a resort of old coaching days, and till very recently a retreat of vastly soothing atmosphere and archaic habits. It was torn down in 1897 and its neighbour the Black Bull, another coaching inn where Sairey Gamp and Betsy Prig took Mr. Lewsome in their tender care, followed its brother the Old Bell in 1901. Gone!

I will not trace further the melancholy tale of the passing of these hospitable haunts of humanity. Their cheery names and honest fame linger like the taste of old wine and will live in song and story when their successors are forgotten—when the Ritz and the Regent’s Palace pass with as little mercy and with much less grace into unlamented oblivion. I cannot pass on however without recording my deep regret at the closing of the Old Sceptre Tavern in Warwick Street, Westminster. I felt it as a personal loss. It was the summer of 1921 that I last took my way to the Sceptre to find it closed, wherefore I passed a bad afternoon. It was one of the best surviving chop houses.

Bishopsgate

Through Bishopsgate, the street that took its name from the gate enters London from the north. There stood some famous inns, among them the Bull, the White Hart, the Green Dragon and the four Swans, destroyed in 1873. They stood in Bishopsgate Street Within, along with St. Helens and St. Ethelburga, two of the churches within the walls that escaped the great fire. In Bishopsgate stood till recent years two houses of great distinction and historic fame. Each was a private house and each was built by a rich London merchant and bore eloquent testimony to the style in which London merchants lived in the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries. The first to go was the last built—Sir Paul Pindar’s house that stood in Bishopsgate Street Without. Its fine carved oak front is preserved in the South Kensington Museum together with one of the ceilings. Sir Paul was the type of the successful seventeenth century merchant and man of affairs. He was at one time Ambassador to Constantinople and among the treasures he brought home from the East was a diamond valued at £35,000 which James I used to borrow from him to wear on State occasions.

The other residence to which I have referred is Crosby Hall, built by Sir John Crosby in the fifteenth century and demolished in 1908 to make room for a bank. Crosby Hall that stood in Bishopsgate Street Within,2 had many distinguished tenants, among them the Duke of Gloucester, afterwards Richard III. Shakespeare must have known it when it was entire. He shows us Gloucester making engagements in Crosby Hall with various people from the Lady Anne to the First Murderer. Parts of it afterwards were destroyed but the great Hall, 90 feet long, 45 feet wide and 40 feet high, with its fine oak timbered roof remained intact till the present century. When Crosby Hall was taken down in 1908, this part of the old edifice was reërected at Chelsea on the site of Sir Thomas More’s house where it is used for lectures and concerts and where it served during the War to shelter Belgian Refugees.

1 See Hogarth’s drawing in The Harlot’s Progress, fourth in the series.

2 Since 1910 the words Without and Within have been dropped from the names of the different parts of this Street. The whole thoroughfare is now known as Bishopsgate Street. The wards, however, retain the old names. Two tablets, one at the corner of Wormwood Street and the other at the corner of Camomile Street mark the position of the gate.