3rd Gentleman.

So she parted,

And with the same full state paced back again,

To York where the feast is held.1st Gentleman.

Sir, you

Must no more call it York place, that is past,

For since the Cardinal fell that title’s lost,

‘Tis now the King’s and called Whitehall.3rd Gentleman.

I know it,

But ’tis so lately altered that the old name

Is fresh about me.

From Trafalgar Square the street that runs due south is called for the first few yards Charing Cross. At its southern end it is known as Parliament Street. Its main course between is Whitehall, the broad way that takes its name from the Royal Palace that witnessed so many vivid events in English History. Today the name associates itself with the government of the British Empire. It contains all the Offices of that government and it contains Downing Street. To the stranger visiting London therefore it promises something of the awesome thrill that is evoked by the presence of power. Here are the seats of the mighty. Here is the powerhouse of the Empire. The visitor starting from the base of Nelson’s monument passes the statue of Charles I and following the direction of the Monarch’s gaze, he presently finds himself in Whitehall. At his right is the Admiralty. On his left he passes the War Office, then on his right rises the Horse Guards, then the Treasury. The buildings tower above him, worn and weather stained like a line of cliffs. Suddenly on his right there is a narrow opening, a cleft in the rocks and the visitor sees the words DOWNING STREET. It is not a street, it is a narrow opening like a cave in the uncompromising line of cliffs. The visitor pauses. He is thinking of lions. The figure of a lion has been somewhere in his mind since he left Trafalgar Square—a huge and imposing lion couchant. With a startled feeling the stranger realizes that he has reached the Lion’s den. It is in that cavern marked Downing Street. The mouth is guarded by a policeman whom the stranger considers with some misgiving. He stands motionless and resembles other London policemen; he is without arms of any kind and there is no menace in his pose. Reassured, the stranger takes his courage in his hands and ventures within. He sees a narrow vista, short and open at the other end, and in the distance a leafy perspective, calm, placid and detached. The visitor is half relieved but more than half disappointed. He ventured into the Lion’s den and it offers the prospect of a little gateway leading to a playground open to the sky. He stops uncertain and looks about him. Close at hand is a row of three small houses, dingy and unpretentious, with perfectly plain brick fronts. They all look alike and are altogether unimpressive. The threshold of each small door is on the level of the pavement of the public thoroughfare and without the smallest vestige of protection. The nearest door has the number 10 plainly marked so that the visitor may not go wrong. It is 10 Downing Street, the official residence of the Prime Minister and First Lord of the Treasury, trying to efface itself from the public eye. It takes the stranger in London some time to be reconciled to this discovery and to get over a feeling that almost amounts to the resentment of one who has been trifled with. When he becomes more accustomed to Whitehall however, Downing Street grows upon the stranger and in time leaves an impression of great dignity that goes a long way to restore his preconceived ideas. But no one can forget his first view of that modest tenement or the feeling of wonder that it leaves on his mind.

Image Number: 22666

From the Thames to St. James’s Park, the whole district was included in Whitehall Palace. Its history begins in the thirteenth century when Hubert de Burgh, who owned a palace on the bank of the Thames, bequeathed it to the Dominicans. The Black Friars never occupied the property but sold it to the Archbishop of York, and it was thereafter known as York Place. For two hundred and fifty years it remained the town house of the Archbishops of York and the last of the long line of prelates to occupy it was Cardinal Wolsey. It then acquired a splendour to match the pomp in which Wolsey lived.

The House of his predecessors was not on a scale to meet Wolsey’s needs. It was not ample enough to contain the power with which he saw fit to surround himself. He therefore built himself a palace on a magnificent scale and furnished it in a style of surpassing richness. When Wolsey fell like Lucifer from that dizzy height, Henry took over York Place and in his turn built even more magnificent additions and added a tilt yard and a cockpit, together with new tennis courts and a new bowling green. The Palace completed by these two builders was of brick and in the same style as Hampton Court. It was of a prodigious size for it covered twenty three acres. Hampton Court Palace covers eight acres and Buckingham Palace only two and a half. It was Henry who changed the name from York Place to Whitehall.

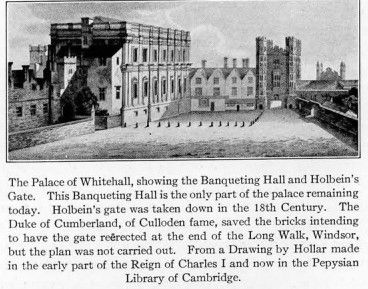

The palace precincts were intersected by a narrow public way called King Street nearly on the line of the present Whitehall. To protect the royal domain Henry erected two fine gates on this street, one to the south called King Street Gate and the other on the north called Holbein’s Gate, a towered structure designed by the artist after whom it was named. These gates were removed in the eighteenth century. Under Elizabeth the chief Royal residence was at Whitehall and the brilliant court of the great Queen more than matched its earlier fame. James I intended to build an entirely new palace on the site of the old and plans prepared by Inigo Jones contemplated an enormous building covering twenty four acres, unmatched in Europe for size and magnificence. The work was begun and, but for the misfortunes of the Stuarts and their constant financial difficulties, it would have been carried to completion. The only part ever finished was the Banqueting Hall, which stands opposite the Horse Guards and now contains the collections of the Royal United Service Museum. In 1697 all of the buildings of Whitehall Palace except this new Banqueting Hall were burned to the ground and the court removed to St. James’s. That ended the career of Whitehall as a Royal residence. Most of the grounds were given away or sold and parts of them are now occupied by Richmond Terrace, Montague House and Whitehall Gardens.

Underneath the Board of Trade Buildings in Whitehall Gardens is a large vaulted chamber with heavy groins. It is thirty feet wide and seventy feet long and fifteen feet high. It is reached by a doorway having a flat pointed arch in a square architrave with shields in the spandrels containing the arms of York and those of Wolsey. This chamber that shows all the properties of Tudor architecture was the great Cardinal’s wine cellar. It is all that remains of Wolsey’s building and together with the Banqueting Hall of James I is all that is left of the great palace of Whitehall.

To recall the associations of Whitehall would be to recall the history of the English court for one hundred and fifty years, under Tudor and Stuart. There Shakespeare places the meeting of Henry and Anne Boleyn at a festival given by Wolsey. There Henry married Anne and there he died. It was there that Cromwell died. There the revelries of Charles II and his court took place. There Monmouth pled in vain with James II for his life after the battle of Sedgemoor and thence James went into exile in 1688.

Image Number: 183139

But one event that associates itself with Whitehall stands out in sharp relief, detaching itself from all the others and making the name a symbol for all ages. The execution of Charles I is English history but London’s part in that business must be recalled. At the outset of the trouble the City was solidly Royalist, though if anyone had cause for grievance, it was the Londoner. Only the unaccountable and almost incredible blunders of the King turned a majority against him. In 1641 Charles was splendidly entertained at the Guildhall by the Lord Mayor and the City officials. Then came the attempt to seize the five members of parliament. It was an act without precedent for the King to enter the House of Commons, and when he appeared in that chamber the five members had taken warning and fled to the City where they hid themselves. The next act of the King lost him the support of London. He entered the Guildhall while the Lord Mayor was presiding at a meeting of the Common Council and demanded the arrest of the five members of parliament who were hiding in London. This act was a violation of the City’S rights, was accordingly resented and the royal request refused.

On January 10, 1642, King Charles I went out from Whitehall to join his army and when he returned seven years later, it was to mount the scaffold erected by his enemies in front of the Banqueting Hall of the Palace. If Charles had kept London on his side he could have won. Without the City’S support he lost. When it came to war, official London was on Parliament’s side and the City trainbands went out to join the parliamentary forces, but even then and to the bitter end a strong minority in London remained Royalist.

When on January 6, 1648, the parliament created a court to try the King it was apprehensive about the attitude of the City. Therefore, an election of the City Council taking place at that time, parliament prevented all but its known friends from taking part in that election. The Lord Mayor who was known to be a man of independent mind was thus left with a Council that did not represent London but represented only the parliamentary faction. When, on January 18, the Lord Mayor came to the Guildhall for a meeting of his court he was confronted by a Council that refused to take the oath and immediately proceeded to draw up a petition to parliament signifying their assent to the trial of the King. The Lord Mayor and the Aldermen then left the hall. In the absence of the Lord Mayor there was no court of the Common Council but that did not prevent the councilmen from going on with the petition.

The court created to try the King met in Old Westminster Hall. Among the judges appointed by parliament were five London aldermen. Three of these refused to attend and the other two though present took no part in the proceedings. When the time came for the members of the court to sign the King’s death warrant, the Londoners refused. The City therefore took no part in the trial and never gave its assent to the execution. On the other hand the City took no active steps to save the King although there were signs that caused the parliament uneasiness. As the King passed out of Westminster Hall after his sentence had been passed, the crowd of citizens filling the lower end of the ancient edifice had shouted “God save the King.”

Now London had always claimed the right to a separate voice in the election of a king and on the same ground might exercise the prerogative of a separate demand in the momentous events that were now developing. But the Lord Mayor, having a Council that did not represent the City but the King’s enemies, was deprived of the constitutional means of giving expression to the City’S right or the City’S will. If the Lord Mayor had led a popular movement on behalf of the King, he might indeed have prevailed but he would be acting not as a magistrate but as the leader of a popular demonstration.

The scaffold was erected in the road in front of the Banqueting Hall of Whitehall, now the Royal United Service Museum. Charles, having slept at St. James’s Palace, walked across St. James’s Park

on the morning appointed for his execution, entered the Hall and stepped upon the scaffold through an open window that is now marked with a tablet. Troops of his enemies were placed between him and the citizens. Two bodies of troops marched back and forth between Westminster and Charing Cross to prevent the crowd from forming. Charles appeared calm, self possessed and very kingly. His speech, heard by few, has been imperfectly reported, but it shows him in full possession of his wits and with a clear perception of the rights and wrongs of his cause. It also shows a courage that was proof against suffering and disaster. The crowd, regarding him in that supreme moment, was profoundly moved. An eyewitness wrote as follows.

The blow I saw given and can truly say with a sad heart, at the instant whereof, I remember well, there was such a grone by the Thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again.

The tragedy of Charles I is that like the rest of the Stuarts he did not understand his subjects. Had he possessed that knowledge of his people that is the security alike of sovereigns and of realms and makes for the greatness of both, his reign might have been one of the most brilliant in English History. The foreigner in London today is impressed at once by the strength and security of the Throne. If he comes from parts where Republican institutions prevail he is sometimes surprised at the immense influence that the Crown brings to bear on the national life, an influence that makes itself felt to the farthest confines of the Empire. It is true that the secret of that overshadowing power of the Throne is not to be found in the Constitution. From that unwritten law one must appeal to the presiding genius of English History. The secret begins to reveal itself to a superficial observation in the brilliant exercise of a gift for understanding their subjects that belongs to the present occupants of the British Throne. It is further explained by the sensitiveness of the same subjects to that understanding, and their quick response to the gesture of intelligence and sympathy. The subjects of Charles I were just as sensitive as the subjects of King George and could he but have shown them a fraction of that penetration of their minds and that knowledge of their hearts that the subjects of George V are accustomed to, he might have led them to great ends. The difference today is in the monarchy itself, not in the people; it is in the sovereign, not in the subject. That is a lesson that London teaches. The Capital that has dealt with its kings for a thousand years has demonstrated to the world a pattern of Constitutional Monarchy that claims allegiance in lands as far from London as it is possible to travel on the circumference of the earth. True, this theme belongs in National History, but London has always led the national aspirations and represented the national cause. It is also true that the course of political evolution and the trend of Imperial development are among the causes of the present ascendancy of the Crown—but these aspects of Constitutional government in England are closely related to the great role of London as the Capital of the Empire.

London Under the Commonwealth

Parliament having removed the King, it passed an act abolishing the Monarchy. Since the Lord Mayor would not do its bidding he was put in the Tower and fined £2000. Then the City at the bidding of parliament elected his successor to whom was assigned the duty of reading publicly the proclamation abolishing the Monarchy. It was greeted with hoots and groans. Two of the aldermen who failed to attend the ceremony were called before the bar of the House where one stated that he had taken the oath of allegiance to the King and could not be absolved from that oath. The other stated that the whole business was obnoxious to him. Both were deprived of the right to hold office.

Image Number: 22677

But London was going through a new chapter of experiences, different from anything it had known. There was general prohibition of old sports, pastimes and favourite amusements; pageants were forbidden ; the theatres were closed. Ancient monuments that enshrined the popular traditions, idols of the City, like Eleanor’s Cross at Charing and Eleanor’s Cross at Cheapside, ancient emblems of a great King’s love and a great public grief, were demolished to reprove the sin of idolatry. There was no protest, for the City had been weakened and wearied by the war, and besides it was threatened by the army of parliament. Yet things were happening. Charles, already regarded by many as a martyr, began to assume in the popular estimation the likeness of the crucified Christ. All the nobler qualities that had been his were present in men’s minds. They remembered the scenes in Old Westminster Hall and they recalled his bearing on the scaffold. They began to talk of his son in exile, and they began, first in secret and then openly, to drink to the health of King Charles. The City Council, no longer subservient, called out six regiments of City militia and began to repair the gates and replace the great chains. It was London’s old, old way: mend the walls, close the gates, up with the defenses. Then General Monck, under orders from parliament, entered London with the army and took up his quarters in Whitehall. No one knew what he meant to do. Parliament dissolved the City Council, ordered the gates to be removed and instructed General Monck to occupy the City with his troops. Monck complied by holding a conference with the Lord Mayor and Aldermen. The repairing of the gates went on. Then from within those gates Monck began to issue demands upon parliament which now discovered that the army of General Monck had been won over by the City. Now people talked openly about the Restoration. The Skinners Company placed the Royal Arms on the front of their Hall and a man climbed up on the Royal Exchange and removed the motto that had been placed there by the Government. The Council issued a proclamation disavowing its acts during the last twenty years and expressing a hope that the country would now return to the old order of King, Lords and Commons.

London and the Restoration

Meantime the old parliament had dissolved itself and a new one was elected. It was Royalist through and through. The Royal exile was waiting at the Hague. A commission was sent to him by the new parliament and by the City and he was proclaimed King. Then the feelings of the City broke loose and got beyond all bounds. Even Pepys thought the crowd went too far. Bonfires were lit, everyone was made to go on his knees and drink the King’s health. Monck’s soldiers were feasted till there wasn’t a sober man among them. To pay their respects in proper form to the Rump Parliament they carried around on poles, rumps of mutton and of beef which they roasted at the bonfires and ate while they drank deep and roared their duty to the King. Pepys wrote in his diary that he went home at 10 o’clock—a very late hour—and left it going strong.

The old sports and pastimes came back with a great rebound. Theatres were opened, maypoles went up with shouts of approval, with dancing and the pleasant sound of pipes. The people had not forgotten how to play. After the winter of their discontent their spirits ran high like a stream in springtime freed from its bonds of ice. All the little things they cared for were made their own again, as life and youth came back to the ways they are wont to go.

Charles was received with tumultous demonstrations and his entry into the City brought back all the splendours of Mediaeval pageantry. The repudiation of puritanism and its ways was complete and overwhelming. King and people together came back to their own in a blaze of glory. They came back to their own together—the King and his subjects. They still had many differences to adjust between them, many disputes and many old scores to settle before they were to meet after many generations to work together for the fulfillment of their common destiny. But they had come back together and they were happy in the event. Whatever happened afterwards, they never permitted themselves to be without a King.

John Milton, secretary to Oliver Cromwell, wrote a pamphlet on behalf of his employers to justify the execution of Charles I. One of the charges that he brought against the King was the charge that he had been in the habit of spending hours in solitude reading the works of William Shakespeare. That was not in the catalogue of sins compiled by the enemies of Charles II. He was a real sinner and a very different type of man from his father. He kept his mistresses at Whitehall and his court was gay and festive, but the wicked, profligate and corrupt court that figures in contemporary gossip and literature and in the minds of later generations is a fiction. The losing side had to have its revenge somehow. Charles was a shrewd and masterful monarch whose days and nights in a large measure, were spent in outwitting everyone with whom he found himself in conflict on his way to supreme power. His court at Whitehall had manners that might have shocked some of his predecessors. It doubtless would have enraged Cromwell and we know that it offended Milton, but the days of the puritans were over. The Restoration was the sequel to that episode; life had entered its protest; the language of the day rang with life’s challenge; the manners of the day proclaimed Nature’s revulsion and the Court at Whitehall was the undisguised emblem of the common revolt.

St. Jame’s Palace, Buckingham Palace and Marlborough House

In the tenth century there stood, westward from the City a hospital dedicated to St. James the Less. On the site of that hospital Henry VIII built in 1522 a hunting lodge from plans by Holbein. That hunting lodge was the nucleus of St. James’s Palace that retains in its gate on the north, in the chapel and in the presence chamber parts of the original structure. When Whitehall was burned down in 1697 the Court moved to St. James’s. It is no longer a Royal residence but its tradition is so persistent that the Court is still known officially as the Court of St. James’s. The King’s levees are still held at St. James’s Palace and the Prince of Wales when in London lives at York House which is that part of the Palace to the west of the old gate that looks up St. James’s Street. The Palace is a brick structure, low and picturesque, built about a number of courts. In the Friary courtyard opening on the east side, there takes place every morning at 10.30 one of those colourful sights that belong to London, the changing of the guard. For that event the crowd never fails to arrive punctually. It takes place, irrespective of the weather on every day of the year and there are three hundred and sixty five days in the year if not more. It is one of four or five free shows that take place with the same punctuality and a very fine and gallant show it is.

Opposite St. James’s Palace across a narrow road called Marlborough Gate that connects the Mall with Pall Mall is Marlborough House, built by Sir Christopher Wren for the Duke of Marlborough. There Edward VII when Prince of Wales, brought his young bride in 1862 and there they lived till Edward’s accession in 1901. There the present King was born and there Queen Alexandra returned after the King’s death in 1910.

The history of the Palace in which the Court resides today, Buckingham Palace, splendidly situated at the west end of the Mall does not take us so far back in history as the other Royal Residences that were successively occupied by the sovereigns since the early Saxon Kings. It is the newest of them all and though it belonged to George III who bought it from the Duke of Buckingham, and although George IV altered it, Queen Victoria was the first monarch to make Buckingham Palace a Royal Residence.

Westminster Palace, The Tower, Whitehall, St. James’s, Kensington Palace, Buckingham Palace, these are the successive Town Residences of the sovereigns since the Saxons. Of each of these some part at least remains, but of Bridewell, which was also a Royal Residence nothing is left.