After floating with the tide up the Amazon River for several days in a small canoe we turned north into a large river and continued our journey for some hours, or until we received a commanding signal, from a house on the left bank, to come ashore.

Two statements must be amplified before proceeding with our story. First, children in our public schools are told the old story of a captain who signalled a passing ship three hundred miles from land and asked for water. The ship replied, “Drop your buckets over the side, you are in the fresh water of the Amazon.” The story is almost universally believed by the common man today. Why not believe it? The Amazon is the biggest river in the world and, besides, we like big stories.

We drifted with the tide two hundred miles up stream. When we had high water in the rainy season and low tide we made coffee within twenty-five miles of the sea, but when we had low water and high tide our coffee was salt at a distance of seventy-five miles. The cattle and horses on the eastern end of the island of Marajo in the mouth of the Amazon never get strictly fresh water to drink, except a little during the rains, because the streams here flowing into the sea are always salt. While the tide actually flows up stream two hundred miles the water rises on account of the tide for a distance of four hundred miles.

The second statement is with reference to the signal. The ever present Winchester rifle is used for many purposes besides that of getting game. It is often the strongest argument used in settling accounts of all kinds. Its presence alone may be sufficient to prevent discussion. We saw it used in telling effect more than once in the adjustment of claims for rubber or women. In the earlier days its word was final in settling financial accounts. Dead men collected no bills at the company’s office at Para or Manaos. The company could not be held responsible for accidents occurring up river. As in every pioneer community far removed from courts of justice, so here the people must be a law unto themselves. In the application justice sometimes goes astray.

The rifle is used also for the transmission of information. No complete code has been worked out but certain signals are recognized by all. An established number of shots may be either a simple salutation, an order to come ashore, an invitation to a feast or a funeral, a request to aid the sick or one in trouble. The traveler soon learns the meaning of all these signals and pays respect to them because it is often a matter of life and death to him or to someone else. He may receive a signal today but he may be sending one himself tomorrow.

When we received the invitation which was at the same time an order to report ashore, we obeyed at once, knowing that if we disregarded it we should be fired upon immediately. We were asked where we were going—a question everybody asks of everybody else as a matter of etiquette in these out-of-the-way corners—and when we replied that we were on our way to visit the Apalaii Indians we were informed that the journey was impossible. In the first place the Indians did not live on that river, besides and much more important, we did not possess a written permission from the “Colonel “—the man who controlled the river. The Colonel was at that time conducting some work on another river which he also controlled. These rivers are as large as the Allegheny and the Monongahela but they are parallel and this gives him control of all the territory lying between them.

A wise man does not argue the point with the muzzle of a rifle, so we immediately altered our plans and endeavored to be just as well pleased—an attitude one must adopt when traveling in this region.

Museum Object Numbers: SA759 / SA764 / SA767 / SA768 / SA771

Image Number: 20756

We spent the night here and as usual in rubber men’s homes found sickness and a lack of medical supplies. A woman was dying of fever and her daughter of ten or twelve had not walked for two months on account of ulcers on her leg. A few grains of quinine would have prevented the fever and ten cents worth of salve have cured the ulcers but they had neither medicine nor money. This is a typical example of the criminal negligence of many “Colonels” in the valley. Our expedition rendered aid to hundreds of rubber men and Indians and gave away thousands of doses of quinine and other medicines. As we never returned by the same route we were deprived of that satisfaction one so much enjoys of seeing his charity patients recover. We were casting bread upon the water. In the same spirit we planted millions of seeds of edible fruits along the banks of many rivers. Some other traveler will reap the benefit of our thoughtfulness and be thankful.

We paddled back to the Amazon and down to a house on the left bank where we spent the following night, or a part of it. Here we learned that a launch was due to call within a day or two at a station on an island fifteen miles out in the river. As the waves make it exceedingly dangerous to paddle a small canoe after the trade winds begin to blow, we set out on our long voyage at three o’clock in the morning and arrived at our destination about nine. The time selected for the start was near the middle of the outgoing tide. I steered straight for the opposite bank without making allowance for the drift of the tide knowing from former experiences that the returning tide would bring us back to our proper station. How one appreciates the blessings of a tide! Had there been no tide or had we been crossing farther up with a four mile current we should have crossed in the same time but we should have landed twenty-four miles down stream. In either case had we steered straight for our objective we should have spent the day in crossing and possibly have been swamped by the waves.

The launch arrived the morning of the third day after and we embarked for the mouth of the river along whose banks the Apalaii were supposed to live. There we were to find the man who controlled the productions, the transportation and the lives of the people of the two rivers, the Paru and the Jary. Upon our arrival at two a.m. we found him pleasant and hospitable, but when we spoke of a visit to the Apalaii he told us that it was not a convenient time for such a long and dangerous journey, that we should wait three or four months until conditions were better suited for interior travel. Appreciating and understanding the situation we remained aboard the launch and returned to Para—but not in despair.

It was in 1915 and war was in progress in Europe. The German Consul at Para had interests in common with the owner of the rivers. Mr. C.N. Unckle, a German scientist, was stranded in Para. So it was arranged through the consul to send Mr. Unckle to visit the Apalaii and to make studies and collections for our expedition. He joined the rubber gatherers on the Pant and spent the whole month of August in reaching the first Indian village where he remained for six weeks living, traveling and trading with the natives. He suffered severely from lack of food and from fever but was unable to leave until the rubber men returned to carry him out. He reached Para more dead than alive but with a splendid collection which he had made during the early days of his visit. Thanks to the Indians who accompanied him down river the collections were saved in a perfect condition. The delicate specimens of pottery were wrapped and tied up in palm leaves so perfectly that not a single one was broken. The great feather headdress was demounted and the feathers placed in bamboo joints to protect them from the insects and the elements. While Mr. Unckle was not able to travel among many villages or to see many of their ceremonies he made a very good representative collection of their handiwork and recorded much of their language, customs and traditions. He greatly regretted that his photographs were a complete failure due to climatic conditions and illness. The photograph, Fig. 40, showing house types is the only one of ethnological value saved.

Museum Object Number: SA773

Image Number: 20818

Mr. Unckle was the third scientific traveler to visit the Apalaii. Mr. J. Crevaux went across from French Guiana and down the Paru in 1883 and Mr. C.H. de Goeje in 1906 went up the Tapanahona and down the Paru, but neither of them gives much information concerning the people they met on the way.

The Apalaii occupy the middle course of the Paru river for a degree or more on either side of the equator. In earlier days they came down to the Amazon but the presence of the rubber man has driven them beyond the first falls. Their nearest neighbors on the north, or up river, are the Roucouyenne who are also members of the same great Carib stock. No one has traveled across country through northern Brazil hence it is not definitely known what tribes occupy the territory in the interior away from the rivers. Here is a splendid opportunity for some one to do a very important piece of exploration—to follow the equator from the Rio Branco to the Jary and thence northeast to the mouth of the Oyapock—a distance of a thousand miles. There are reports of great savannahs but no one knows their location or extent. A few years ago a concession for several million acres was obtained from the government and a great company formed to stock the lands with cattle. A party of engineers was sent into the region at great expense to survey and mark out the boundaries but the savannah could not be found.

Museum Object Number: SA771

Image Number: 20757

In the present article I shall not attempt to do more than to describe the specimens here illustrated and to give some account of the ceremonies in which they were used. The large vocabulary and other linguistic material will be published later along with similar material from other tribes of the Amazon.

The great feather headdress, Plate VIII, is used by the medicine man in ceremonial dances in which he performs the leading part. It is worn also by the war chief and by the initiate during a part of his puberty ceremony. Fig. 41 shows the war chief in full costume ready to lead a band of warriors in a dance preparatory to setting out on a raid or in the celebration of a victory.

The foundation of the headdress is a rather crudely woven high hat made of arrow reeds and palm frond splints. As the hat is entirely covered with feathers its structure is unimportant except that it must be sufficiently strong to carry the long feathers. There are nine bands of small feathers around the hat. The feathers of each band are strung or woven on cotton cords and tied around the hat in proper position. The long feathers at the top are fitted into a reed which runs along the top of the hat. At the conclusion of a dance or other ceremony in which it is used the headdress is dismantled and the feathers stored in joints of bamboo for protection against the elements and destroying insects. These headdresses are considered very valuable by the Indians because of the difficulty in collecting the feathers and the time and skill required in making them up.

The long red feathers are plucked from the tail of the great macaw; the white streamers at the top are made of eagles down; the ornamented sticks attached to the long feathers are covered with feathers from the humming bird; the pendants attached to these are of beetles wings. The first band of white below is made of feathers from the harpy eagle; the black hand, from the curassow; the yellow, from the oriole; the green, from the parrot; the yellow and the red from the macaw; the red, from the macaw and the white bands around the brim are of feathers from the eagle and the egret. None of the feathers is artificially colored.

The streamers of the headdress and the cloak of the chief are made of strips of bark dyed black with the juice of the genipa.

The great macaw is the most difficult creature of any in the forest for the Indian to capture. It flies high and alights on the topmost bough of the tallest tree. When it feeds it plants a sentry for its protection. To capture it the Indian builds a blind in the top of a tree and secretes himself there until the macaw alights when he shoots it with a blowgun and poisoned arrow.

Ordeals

The puberty ceremony is an endurance test required of boys before they can be admitted to the company of men or take part in the councils of the tribe. The ceremony which lasts for twenty-four hours is usually taken part in by three or four boys at a time. Some are unable to endure the test and fall out to try again at another time. At daybreak the boys, unadorned, with staffs of arrow reeds in hand gather under the direction of the medicine man. They partake of some food which has been especially prepared for them and just at sunrise, which on the equator comes very soon after the first streaks of light, they repair to the dance ground where they sing and dance the whole day through without rest or refreshment. During the day the medicine man and his assistants make up the large headdresses, make the wasp frame, Fig. 42, and fill it with live wasps. At the setting of the sun, the boys who have endured the strenuous dance present themselves before the medicine man who applies the wasp frame to their chests, backs, arms and legs. Those who scream or who betray any visible signs of suffering when they are stung are not allowed to continue the ordeal. Those who have been brave and have not revealed their sufferings, put on the great headdress and, carrying the flute, Fig. 43, in the left hand and a dance arrow in the right, proceed to the dance ground where they dance around one behind the other over the dancing board, blowing their flutes and waving their dance arrows until finally about midnight they fall exhausted on the ground. They attempt to rise and continue but others surround them with mats and palm leaves and compel them to lie on the ground until the medicine man gives the signal for them to jump into the river for a bath. When they return the medicine man gives each his first loin cloth, cuts off his hair over the forehead and decorates him with strings of beads and a bandoleer of monkey’s hair.

Museum Object Numbers, from Left: SA766 / SA772 / SA724

Image Number: 20791a/b

The preparation of the dancing ground is interesting, but common among east Carib tribes. A large plank is made from the flat root of a tree and placed over a deep hole in the ground in which a sacred bundle has been deposited. The board is then covered with clay thus making a hollow-sounding dance ground. The sound of the dancing feet may be heard a long distance and adds rhythm to the music of the flute. The board thus serves the purpose of a drum but this is not its primary function. It is used as a method of communication with the deity to notify him that the dance is in progress.

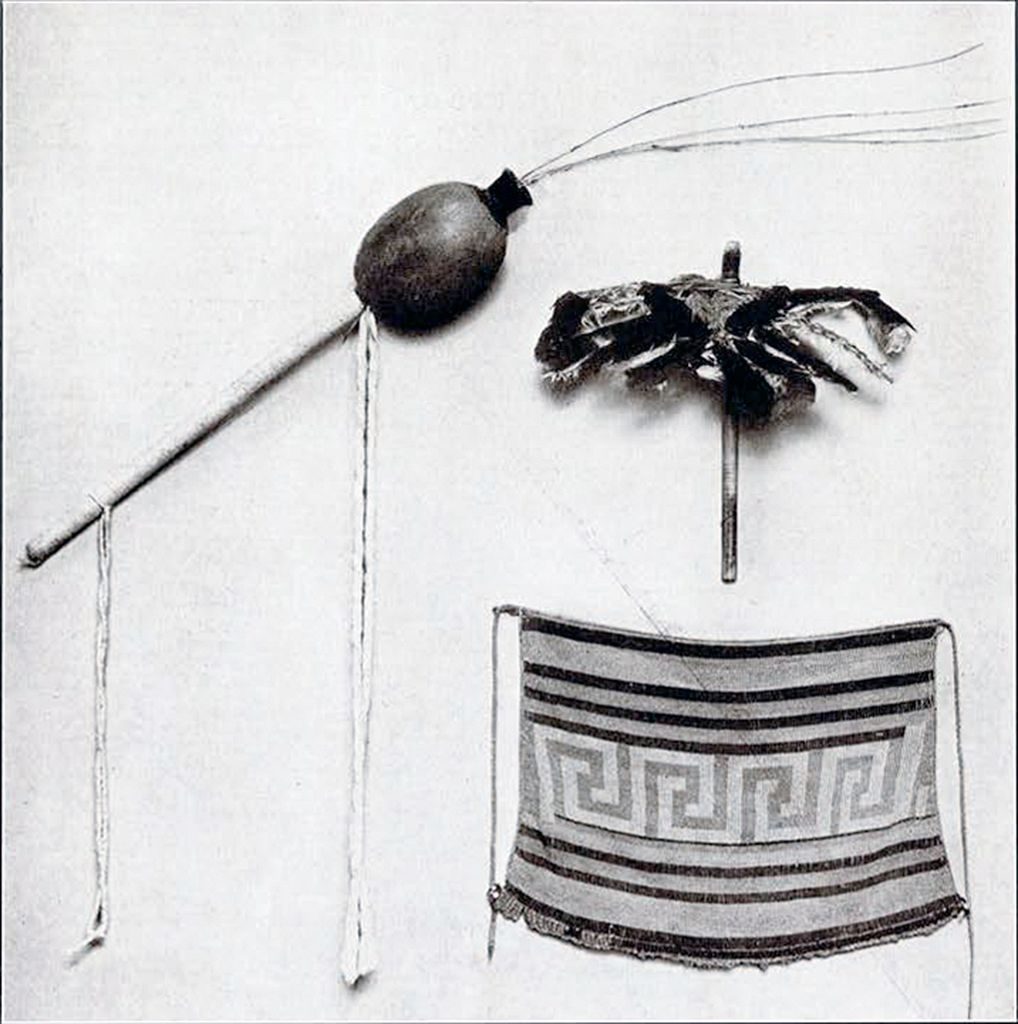

The flute, Fig. 43, used in the dance is made of a hollow bamboo joint wound with cotton and having a reed made of a bird bone inserted through the septum at the lower end. A decorated calabash attached at the reed end serves as a resonator. They have other flutes closed with wax at the upper end and blown with the mouth at a lateral hole. The hunter’s horn is made of a joint of bamboo two inches in diameter and ten inches long. It is blown through a square lateral hole and may be heard a long distance. The number of blasts informs other hunters what kind of game has been discovered.

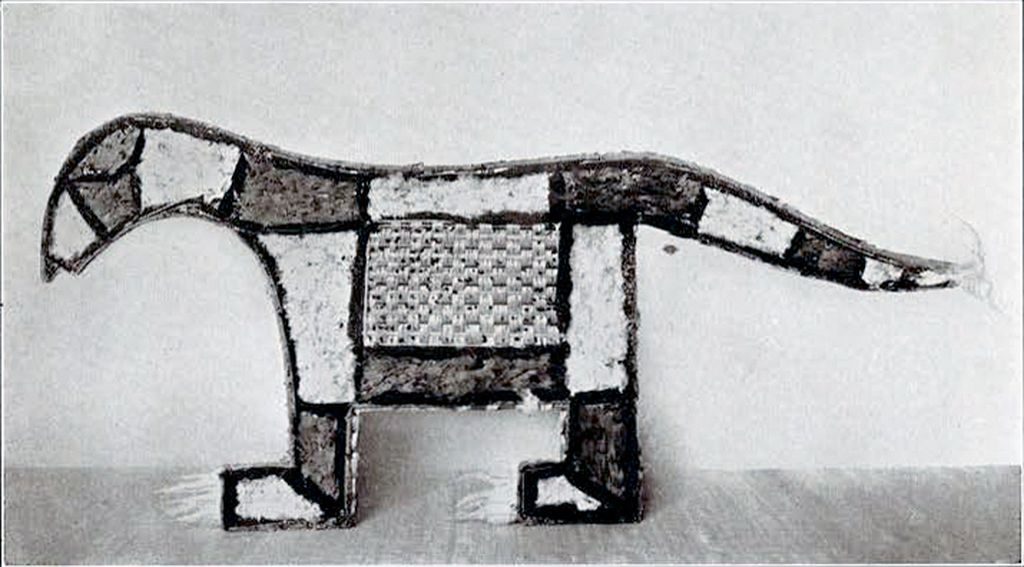

The wasp frame, Fig. 42, is usually constructed in the form of an animal, bird or fish. The central part, six by eight inches, which contains the wasps is made of wicker work of soft material. The heads of about a hundred wasps are passed through the splints or at the interstices. In this uncomfortable position the wasps are ready to sting upon the slightest provocation. The other parts of the frame are covered with feathers of various colors in order to make the animal appear as realistic as possible. Instead of wasps, large black stinging ants are sometimes used for the same purpose. The exact distinction in the applications of the two insects is not understood. Ants are used to sting certain parts of the body while wasps are used for other parts; ants in some ceremonies and wasps in others. There may be some sentimental reasons for the distinctions in use or the stings may produce different effects upon the parts of the body to which they are applied. The sting of either the ant or the wasp is more painful than that of our domestic honey bee, hence it requires considerable courage to submit to the ordeal of being stung by one hundred of these vicious insects all at once and to have it repeated on five or six parts of the body. Little wonder that some cry aloud with pain.

Marriage

A young man cannot marry until he has successfully passed the puberty ordeals and thus has become a man. More than this, however, is required of him. He must give satisfactory evidence that he will be able to support a family. If he is not a good shot with the bow and arrow he will not be able to kill game and fish enough to supplement their vegetable diet. Therefore he is required to pass the target test. He stands with his back turned and throws cassava pellets at a circle drawn upon a piece of wood. If he does not hit the centre of the circle three times in succession he must repeat the whole endurance test and try his skill again or remain a celibate. In some tribes the girl’s father tests the boy’s ability with the bow by compelling him to shoot an arrow from the bow of a rapidly moving canoe into a birds nest or a woodpeckers hole in a dead tree. If the boy should fail he is allowed another opportunity at a later date.

Museum Object Numbers, From Top: SA757 / SA754 / SA756

Image Number: 20804

A girl must also undergo certain puberty ordeals and endurance tests before marriage. At the first appearance of puberty she must fast in seclusion for three days, during which time she is not allowed to talk. She must not eat meat for a month. When her fast is concluded her body is scarified with the sharp teeth of some animal or fish and she is allowed to wear an apron, Fig. 43, for the first time. She is now ready to begin the courtship in which she takes the initiative. She uses certain binas or charms to stimulate mutual affection. By rubbing her hands and face with a particular caladium she causes her favorite young man to think well of her. A woman may use the same charm to prevent her husband from forgetting her while he is absent on a long journey.

When a girl has reason to believe that a certain young man cares for her, she presents him with food and drink and places firewood near his hammock. If he accepts these offerings he thereby accepts the girl for his wife but she must submit to the ant and wasp ordeal before she can go to live with him. Her mother applies the ants to her chest, arms and legs and the wasps to her forehead. If she shows signs of suffering she must repeat the ordeal at another time. If she passes the ordeal satisfactorily, a feast and dance are given in her honor. She does not join in the dance but occupies a stool in a prominent place where she receives the admiration of all present: She now becomes the wife of the young man without further ceremony.

Medicine Man

These ant and wasp frames are used also by the medicine men for remedial purposes, especially for relieving acute pain by the application of the stings to the ailing part. Whether or not the sting has a direct curative value it at least serves the purpose of a very strong counter-irritant. Its best use is for rheumatism and for stiffness after overexertion. We have a belief among ourselves that the sting of the honey bee is good for rheumatism.

The duties, powers and performances of the medicine man are the most varied of any individual in any society. He is the teacher and guide of his people. There is nothing that he cannot do or that he does not know in the natural or spiritual realm. His chief duty is to counteract the evil designs of hostile spirits. He is reverenced and feared by the community and consequently enjoys more liberty and exercises more real power than any other member.

Museum Object Number: SA755

Image Number: 20803

The office is hereditary; the medicine man selecting one of his sons for his successor. The boy must undergo a long period of education and training. He must become proficient in the natural history of the region; he must know the habits of animals and the properties of plants; he must know and imitate the cries and calls of animals and birds. He must learn the technique of the practice of his profession; the proper chants for the invocation of the spirits and the methods of the interpretation of dreams. He must fast and endure pain with indifference. He must submit to an ordeal which may result in his death. That is, he is required to drink a prescribed amount of tobacco juice which produces convulsions. In the trance so produced he sees spirits and converses with them and by them is accepted as a spirit doctor.

In the practice of his profession the medicine man is sincere and believes as implicitly in his powers as do the common members of the tribe. He may not always be able to exorcise an evil spirit or to counteract the evil designs of certain spirits. The spirit may be too powerful for him or the influence of a rival medicine man may be too great. He has one recourse in the case of sickness in his tribe. He can send an evil charm upon the tribe of his rival who is responsible for the particular disease. The charm is sent upon a woman who is always recognized by her own tribe and may be punished or even killed by them because of their fear of the charm.

When a person is sick and the application of common remedies has failed to produce a cure, some member of the patient’s family approaches the medicine man, tells him about the case and requests him to visit the patient and attempt a cure. At the same time he offers the medicine man a cigarette made for the occasion. If he accepts it he thereby agrees to make the visit. He will not accept pay for his services until the patient is cured. This differs from our practice but the next item agrees perfectly. He fixes his fee according to the patient’s ability to pay. Since he does no manual labor, he accepts as pay, food and other necessaries of life. In an extreme case he may even receive a young girl on account. The number of his wives is limited only by his means of supporting them.

When a medicine man dies he is buried and the spirit remains within the body for consultation by other medicine men. The body does not undergo dissolution but remains flesh, as in life. The body and the spirit become immortal.

The frames are used for still another purpose which is somewhat obscure. When an important man of recognized strength, courage, or ability makes a visit to a village a frame is brought out and he is asked to apply it to the different parts of the body of all the inhabitants, men, women and children alike.

A question arises as to the real significance of the use of the ant and wasp frames. Among the Carib tribes the frame is usually in the form of an animal, bird, or fish, and one is naturally inclined to think that it may have some totemic significance. This probability is strengthened by the fact that among the Wapisianas, a nearby Arawak tribe, the medicine man utters a little prayer to some animal when he applies the frame, which, however, is not in the form of an animal. He may say “be as bold as the jaguar” or “be as free from fever as the black monkey” or addressing the deity, “you have power to keep the monkey well now make this patient well.” As already stated, some noteworthy person may apply the frame and he may be a stranger who knows nothing whatever about the use of the frame. Is the efficacy in the effect of the stinging, in the animal represented, in the person making the application, or in the petition to deity? Does the initiate receive the strength and courage of the particular animal to withstand the ordeal or is it the character of the person making the application that he receives? The ideas in the mind of the Indian seem somewhat confused on this point. Any one or all of these ideas may be present at a particular performance.

The Apalaii believe that these ordeals render the parents skilful and industrious and insure the birth of strong robust children. We can easily agree with them. The weak of body or mind cannot pass the endurance tests and hence are unable to marry and perpetuate their weaknesses. The obligation of publicly enduring severe bodily pain without showing signs of suffering certainly demonstrates strength of character and has a real value in the development of the race.

W.C.F.

Image Number: 20835