London’s Continuity

In the days before the antiquarians and the scholars began their violent invasion of the provinces held so long by the bards and the sages, everybody accepted the legend of the founding of London written down by the old Welsh churchman and historian, Geoffrey of Monmouth, in the twelfth century. According to that venerable ecclesiastical authority London was founded by Brute, a grandson of Aeneas, who escaped from Troy at the fall of that city, sailed away with a band of followers, landed in Britain, conquered the race f giants he encountered there and founded New Troy, afterwards called London. We may not believe that story any more but it is such a brave old lie that I always like to tell it.

Image Number: 22663

The picture of London that I have in my mind and that I wish I might present to you is not exactly the London you know so well, the metropolis of brick and stone with its weather stains, its grey sunshine and its fog, but rather London as a living organism with its continuity of life and its persistent tradition. We do not realize what a very old place London is because its history is largely unwritten and it is not yet a ruin where excavations are made to reveal how it rose, layer resting on layer and cycle on cycle. But it is no t antiquity alone that matters. What I want to call attention to is rather that continuity which has persisted without break from the beginning. There has been no conquest, no revolution, no cutting loose from the past. That is fundamental, the enduring essence of London life. I often hear it said that London has experienced vital changes even in our own generation. This is a careless observation, for London has not changed at all and the connection between Chaucer’s London and the London of today is a very close connection.

We must bear in mind that the name London has two principal and quite distinct applications at this day. First it is the name of the CITY1 that lies within the ancient boundaries of London Wall together with a narrow encircling strip. It is identical with the city built by the Romans, including the Pomerium or sacred belt outside the walls on which the Romans did not permit any buildings to be erected. That is the CITY OF LONDON. It is what Londoners call the CITY. Its chief magistrate is the Lord Mayor who within his own boundaries takes precedence of every other subject of the Crown, even of the Royal Princes. It is the London that the King himself may not enter without permission of that same Lord Mayor. It is about a square mile in area and its resident population is less than fifteen thousand. In the daytime except on Sundays, its population swells to more than a million. A million people pass into that square mile at the beginning of every day to their regular occupations and pass out again in the afternoon. It is the London of the Tower, the Bank, the Royal Exchange, the Mansion House, the Guildhall, the houses of the Livery Companies, and Saint Paul’s Cathedral. It is the heart of the Metropolis that is built around it covering 693 square miles and containing a population of seven and a half millions. London the Metropolis consists of the CITY OF LONDON and twenty eight boroughs together with an outer ring.2 The CITY has its own government, its own constitution, its own police, its peculiar customs and privileges and its ancient prerogatives that have been inherited from Saxon and even from Roman times. It has always had its own military establishment called the Trainbands—Trained Bands recruited and officered from the citizens.

“John Gilpin was a citizen of credit and renown

And a Trainband Captain eke was he in famous London Town.”

These ancient military organizations now form seven units in the Regular Army and no regiments in the British Army gave a better account of themselves in the World War than these same old London regiments.

Until the middle of the eighteenth century, the walls of London were standing and you entered through one of the seven gates—New-gate, Bishopsgate, Ludgate, Moorgate, Aldgate, Aldersgate, Cripple-gate. 3 Today the walls are down and the gates are gone but you can always tell when you are within the CITY by looking at a policeman, for the CITY police wear red and white bands on their sleeves and crested helmets whereas the Metropolitan police outside the CITY wear blue and white bands on their sleeves and helmets without crests.

London’s Difference

The earliest traveler who gives a detailed description of London is Fitzstephen who wrote in the twelfth century. I will quote just one sentence translated from the Latin original by John Stow, the Tudor antiquarian. “In London the calmness of the air doth mollify men’s minds, not corrupting them . . . but preserving them from savage and rude behaviour and seasoning their inclinations with a more kind and free temper.” In this and other quaint passages, Fitzstephen records his observation that London is not like any other place. Many writers since have made the same observation and everyone who knows London at all is aware of its unexampled difference. George Borrow expresses what everybody feels when he says: “Everything is different in London from what it is elsewhere. The People, their language, the horses, even the stones of London are different from others.”

Fitzstephen, in the passage I have just quoted, explained it as an effect of climate but I think it can be shown that the difference is due to another cause altogether. It is elemental and primordial; it proceeds from within; it lies deeply embedded in the foundations of life itself ; it concerns the very sources of London’s existence and it is written in every chapter of London’s history. It is a difference as elementary and as obvious as that of gender. London is a masculine city. All other cities are of the feminine gender. Paris is feminine; Rome and Vienna are feminine; Berlin is feminine; Petrograd and Moscow are feminine and New York is also a feminine city. London is the one and only masculine city and moreover it is the most masculine of all things made. Every man feels better in London than in any other city on earth and the reason is that the manhood in him responds and vibrates to the virile drift that whirls about him like the cosmic stream of which worlds are made.

There is but one recorded capture of London, when it was taken by a woman. Boadicea has the unique distinction of being the only person who ever conquered London. Have you ever thought why the suffragettes tried to capture London and let other cities alone? Simply because London is a he city. Those violent women knew perfectly well that if they tried the same methods in Paris or New York, these cities being feminine would know exactly how to deal with them. London didn’t know in the least how to deal with them.

In the London Museum, among the relics of the Stone Age, there is a case containing some bones of a man with a flint spear head sticking in his skull. I understand that these are the melancholy remains of the first unfortunate wight who tried to start something in London. His imitators in every age shared a similar fate till the suffragette arrived, and then . . . But the masculine mind works that way.

Compare the London police with the police of any other city you know. The London policeman wears soft gloves; he carries no club and he has no weapon of any kind about his person, either concealed or unconcealed. In Paris the policeman is armed with automatic pistol and club, one in either side of his belt. In Berlin before the war at least the policeman carried a huge sabre and a monstrous pistol slung about his haunches. In New York—but I need not multiply examples. The difference is one of gender. The masculine mind recoils from even the appearance of violence and brutality. Therefore the London policeman wears soft gloves and carries about his person no suggestion of force. The feminine mind reacts in an entirely different way and therefore these other cities dress up the guardians of the law to make them look like brigands and permit them to behave a good deal worse sometimes. They love the appearance of force; they adore the gesture of violence; they flaunt the emblems of brutality. These cities are of the feminine gender.

A man likes to wear fine feathers and walk in procession through the streets or sit in lordly state. If you doubt it observe the habits of the Lulus or look at the House of Lords. All male creatures are alike in this. The stag’s antlers are not for fighting but for show. Thus London arrays itself in royal purple, in scarlet and in gold, decks itself with feathers, puts on its gorgeous raiment and moves in the stately procession of the Lord Mayor’s Show and all its pompous pageantry—the plumage and the antlers of the harmless male.

London has another obvious quality. It is a silent city. It is more than that—it is one of the silent places of the earth. James Russell Lowell said that London reminded him of the roaring loom of Time. I know very well what he meant and the only fault I have to find with that admirable rhetoric is that London does not roar.4

The stream of traffic rolls in silence over its wooden pavements that are laid like the foundations of the earth and kept like the quarterdecks of the Royal Navy. Stand on the curbstone in front of the Royal Exchange facing that open space, with the Bank on the one hand and the Mansion House on the other. It is the place or near it where the Forum of the Roman City stood, and it is said to be the busiest spot in the world today. Upon that open space converge seven main thoroughfares filled with traffic and its lines of communication are the circumference of the earth. What are your sense impressions? A mass of traffic of every description, a policeman, a few magic passes of his hand and from the appearance of inextricable confusion the traffic rolls in and out through its seven main arteries without interruption, smoothly, silently. There is a mighty murmur that neither rises nor falls; subdued, continuous, steady, insistent, like a psalm intoned. There are no pauses; neither are there any sharp intrusive sounds to strike across that even pulse or shatter that majestic symphony—London’s Psalm of Life. No clatter, no cries, no horns, no noise. It is a silent city.

I do not know that it has ever been said that London is a beautiful city. That could hardly be said with truth. Parts of it are hopelessly ugly. Its monuments, with a few remarkable exceptions, are indifferent or mean. Yet bits of it are among the most beautiful spots on earth and in certain atmospheric conditions peculiar to itself it takes on a quite unearthly splendour. It is not like Paris, that city of splendid broad boulevards and wide open spaces all beautifully laid out like the ideal city of the future. I do not know how any city could be better laid out than Paris. There you have a contrast, for London is not laid out at all. It has no plan and I am persuaded that it is better so, for the English, when they plan anything, are apt to make a mess of it but they have a wonderful way of doing things remarkably well by accident; and London, devoid of plan and heedless of design, is a most splendid accident—like Orion and the Milky Way. It was no human prevision that made London what it is; it was “Time and the Ocean and some fostering Star.”

London’s Beginning

If you would get a comprehensive view of what Time has done for London, go to the London Museum in Stafford House, Saint James’s, and if you would see what the Ocean means to London, pay a visit to London Dock or take a journey through the Port of London that stretches for thirty miles along the Thames from London Bridge to Tilbury Dock.

London Museum is like Time’s Workshop, filled with the refuse left behind by the Master Craftsman. Stuart, Tudor, Plantagenet, Norman, Saxon, Roman, Celtic Briton, Man of the New Stone Age, Man of the Old Stone Age. There you have them all, following each other in a long procession down the ages till they disappear in a Tertiary London fog.

The first people to build on the banks of the Thames where London stands and protect their settlement with earthworks and stockades were the men of the New Stone Age, and they occupied the site for a period of unknown duration. But the time came when these men who fought and hunted with flint spearheads were driven from their stronghold by a new race that appeared from across the channel. The invaders had bronze swords and axes and shields and the natives with their flints, however brave, were no match for so formidable an enemy. These supermen with their new inventions, so mighty in battle, were of the Celtic race which swarming into the Island, soon possessed it, submerging the aboriginal inhabitants and absorbing the remnant. They arrived not later than 2000 B. C. and on the spot where the Walbrook and the Fleet ran into the Thames, they built a stronghold on the higher ground and, on the marshy flats next to the river they built their dwellings, partly on piles. They called the place London, which in the ancient Celtic language means the Stronghold in the Waters, because they were partly surrounded and protected by the Thames which was not then confined within its embankments as it is today, but which at high tide overflowed a wide strip of marsh and at low tide left a broad expanse of mud. But I think they must have consulted the stars when they called it London—Stronghold in the Waters. They worshipped, among other divinities, a god of the waters called Lud, and they built him a shrine on the high ground where Saint Paul’s now stands, and the name of that god is preserved in the name of Ludgate Hill. The name of London therefore and its earliest foundation take us back not less then 4000 years.

These ancient Britons of the Bronze Age had cattle and horses and sheep; they cultivated the land and mined tin and traded with the Continent. During many centuries before the Romans came, London was an important commercial centre as well as a Stronghold in the Waters.

The point has never been definitely set tied as to whether Julius Caesar ever saw London or not. On the evidence it seems very doubtful. In any case it is certain that when Caesar withdrew after four months in the Island, London remained exactly as it had been and continued to grow in size and importance and in the volume of its foreign trade. It had a gold coinage, iron had replaced bronze and chariots were used both in war and in peace. London was a flourishing and a populous city before England was again disturbed by the Romans. That happened in the year 43, ninety eight years after Caesar’s first landing and in the reign of Claudius when Britain was finally conquered and the Romans began that rule and colonization of the Island which lasted nearly four hundred years. During this conquest of 43, London was occupied and a Roman administration installed. In its Latinized form it became Londinium and the very first time that the name appears in writing is where Tacit-us tells us of the capture and burning of London and the massacre of its inhabitants by the British Warrior Queen in the year 61, only eighteen years after the Roman occupation.

Immediately after Boadicea’s revolt had been suppressed, the Romans started to rebuild Londinium and to provide for its defense. They renamed it Augusta but even they found that you can’t change anything in London. It was then that the Romans built the wall and put a new bridge across the Thames. Romans and Britons then settled down together in peace with occasional outbreaks for four hundred years. They intermarried and their offspring are still in London as in other parts of Britain. Under that joint regime London became one of the largest and most important cities in the Roman Empire, a colonia managing its own affairs, very much as it does today, for the Roman Imperial Authorities never interfered with the affairs of a city of London’s importance. It was in reality a State in itself and that fact is at the foundation of London’s present constitution. The continuity is unbroken. In 410 the Roman legions whose presence was necessary for the defense of the province were withdrawn owing to the general stress upon the resources of the Empire. London, like the other cities of Britain, was left to defend itself against the Anglo-Saxon invasion which quickly ensued. Then follows a period in London’s history that has puzzled all historians. Unlike the other cities of Britain, it disappears from history for nearly two hundred years. During that interval of Anglo-Saxon Conquest and Settlement, London is not mentioned at all in the Saxon chronicles though the events of that conquest including the occupation of other cities are all duly set. forth. Some modern historians have interpreted this silence as meaning that London was deserted when the Saxons arrived. According to that view, it stood silent and ghostly within its massive walls beside the Thames and was therefore avoided by the Saxons as a place haunted and accursed. This theory seems incredible from every point of view and other historians have advanced a theory that meets with more and more support as time goes on. It is argued that the silence of the Saxon chronicles can be reconciled with known facts only on the supposition that London simply shut its gates on the invaders, carried on within its walls, and made such a formidable show that the Saxons decided to leave it severely alone. They settled all around and built their villages on the outskirts. Kensington, Paddington, Islington, and all the places with names ending in -ton and -ham were Saxon villages. Finally when the whole country was occupied, when Roman and Briton settled down peaceably with the immigrants, the Saxons were admitted to London on peaceful terms and they gradually assumed their part in the government of the City, introducing their own customs, which continued for centuries to dispute supremacy with the governance of the old Roman City State, Londinium Augusta.

When London is finally mentioned in the Saxon chronicles after nearly two hundred years of silence, it is in the year 604. London is then identified with the East Saxons. It is a part of the Kingdom over which Ethelbert ruled. Ethelbert, the convert of Saint Augustine, had become a Christian. A Bishop was installed in London. Saint Paul’s had just been built, but London was still largely a Pagan City and after the death of Ethelbert and his nephew Sebert, Sebert’s sons renounced Christianity and sent the Bishop to exile in Gaul. His faithful converts however were allowed to keep up the forms of Christian worship in Saint Paul’s.

Nearly three centuries later, when the Danish invasions began, King Alfred repaired the walls of London and made it his base of operations against the Danes by land and sea. After the death of Alfred, the struggle against the Danish invasion continued and London withstood half a dozen Danish sieges in the next hundred years. At last the great Canute, the last and greatest of the Danish leaders, having made himself master of England with the exception of London, concentrated all his resources, naval and military, against the stubborn city on the Thames. The Witan of England had already elected Canute King, but within its closed gates, the Witan of London elected Edmund Ironside King. Then came that heroic year of struggle between Edmund Ironside and King Canute. The siege of London was fierce and of brief duration, for Canute, with his ships sunk and his army shattered, was driven to take refuge in another part of England. It was a wonderful year, that year of Edmund Ironside, but at its end, Edmund died and the Witan of London reversing its former policy, elected Canute King and having brought him to London, crowned him at Saint Paul’s. That is characteristic: first they knock their enemy down, then they pick him up and shake hands with him, and offer him the best they have. In this instance the citizens never had occasion to regret their choice, for next to Alfred, Canute proved to be the strongest of their kings. The Dares settled between the CITY and Westminster, especially in the region called Aldwich. The Church of Saint Clement Danes in the Strand marks the place where these Danish settlers had their place of worship.

King Canute died in the year 1035 within thirty years of the Norman conquest, a short interval that it is very important to remember for it means that when William arrived, there were many men living in London who had helped to defeat Canute and afterwards to make him king.

At the battle of Hastings London was represented by its Sheriff at the head of its citizen army that went out and fought at Harold’s side all day long and when the day was lost, Ansgar, the Sheriff, covered with wounds was carried back to London in a litter. After the battle William marched straight cn London where he found the gates closed and the walls manned. After taking a look at the walls, he made a wide circuit and leaving the City far behind, set up his headquarters at Berkhampstead. London was not afraid of William and he knew better than to attempt what Canute, with much more formidable forces had failed to do. Eventually a deputation of London citizens waited upon the Norman Duke and offered him the Crown on conditions, all of which he accepted, whereupon they escorted him to London to be crowned, but whereas Canute had been crowned at Saint Paul’s, within the City, William was crowned without the City at Westminster Abbey, where every sovereign since his time has also been crowned, and to this very day, the King of Great Britain and Ireland and of the Dominions beyond the Sea, Emperor of India, after being crowned at Westminster asks permission of the Lord Mayor of London to enter his own capital. It is especially worthy of note that William’s Chief of State, the man who, next to himself, was the most powerful man in the Kingdom was Ansgar the Sheriff of London who was carried on a stretcher from the battlefield of Hastings.

London’s Oldest Monuments

When we look about to see what remains to meet the eye in London streets from the earliest periods of its history we find that there is little enough, for the process of pulling down and rebuilding has gone incessantly on with much destruction by fire since the day when Boadicea left the City in blood and ashes nearly two thousand years ago.

One of the very oldest works of man that has successfully resisted the action of time and continues to do service is the Thames Embankment, a wonderful work of unknown origin and antiquity. It is a great system of earthworks lined with stone running from London Bridge down both sides of the River to its mouth—more than two hundred miles of embankment to keep the river within its bounds, reclaiming the marshy land and converting it into tillage. There is no record of its construction, and it is probably a growth of ages, having been begun by the ancient Britons of the Bronze Age.

Another very ancient work to be seen outdoors is the tumulus on Hampstead Heath popularly called Boadicea’s grave. In this case popular tradition seems to be at fault for it is difficult to explain how the queen could have been buried at this place. The tumulus is undoubtedly the grave of some king or chieftain of the ancient Celtic Bronze Age Britons and it is therefore pre-Roman, but more than this we cannot say.

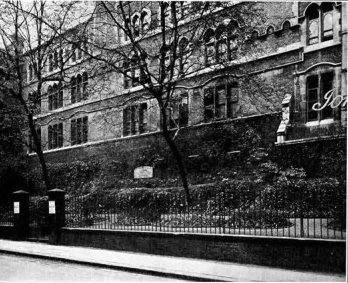

But the very oldest object in London streets is London Stone, which under that name has been closely identified from time immemorial with the fortunes of the City. We are looking at the outer wall of Saint Swithin’s Church in Cannon Street at the point where London Stone is so deeply imbedded in the Church wall that it can hardly be seen. The oddest thing about London Stone is that no one knows what it is and therefore I am going to tell you all about it. What we know about it historically amounts to this. In an early Saxon document it is reported to have been mentioned incidentally, a certain property being said to lie adjacent to London Stone. The Mediaeval Kings after their coronation used to strike London Stone with their swords in token of the City’s submission and you will recall that in Shakespeare’s play of Henry VI the rebel Jack Cade rides into the City and striking London Stone with his sword pronounces that famous speech beginning “Now is Mortimer lord of this City.” It was originally a tall upright stone deeply imbedded in the ground but time and the weather and London fires have reduced it to a stump, a mere fragment. It stood in Cannon Street and when Christopher Wren was building the Church of Saint Swithin’s after the fire, London Stone was imbedded in its outer wall, protected by a stone casing reinforced by an iron grill and securely sealed by virtue of its traditional sanctity. Geoffrey of Monmouth accepting and handing down a legend of his day tells us that London Stone was the pedestal of the Statue of Diana in Troy, and having been brought to Britain by Brute and his companions became the Sacred Altar of New Troy. But London Stone is much older than that. It was an object of great antiquity when the Romans arrived and their predecessors the ancient Britons found it on their arrival more than two thousand years before. It was erected by the people of the New Stone Age and belongs to that class of standing stones found in different parts of Britain and the Continent that from time immemorial have been respected as objects of venerable and sacred associations. To this feeling London Stone owes its preservation. It is a monument of the Stcne Age and the oldest thing in London Streets today.

At a depth of from twelve to twenty five feet below the present pavements are the ruins of Roman London and wherever excavations have been carried to these depths, some relics of Roman life have invariably been found. In the London Museum, the Guildhall Museum, and the British Museum, you may see beautiful mosaic floors that belonged to Roman houses, as fine as anything of the kind found in Italy. You may see statues in marble and bronze, and a great deal of domestic furniture, and every appurtenance of trade and industry as well as the materials of commerce. A Roman galley sixty feet long, dug up from the banks of the Thames, at the Surrey end of Westminster Bridge, is among the most interesting exhibits of Roman London.

Besides these rich collections in the Museums some pieces of the Roman wall remain in position. The largest piece, not far from the Tower, is enclosed in the structure of a huge warehouse, for which reason it is not readily visible to the visitor in London. It is about 120 feet long, 35 feet high, and 9 feet thick. On its top the battlements are still in place and the footway where the sentry used to walk is still intact. In London Museum you can find the spear, short sword and shield used by the Roman sentry and the very shoes in which he walked the battlements.

In a vault deep under ground, below the General Post Office, is the stump of a huge Roman bastian, a grand and imposing relic that conveys a vivid impression of the strength of the Roman walls and the magnitude and importance of the City. There are still a few fragments of the Roman wall in positions where they may be seen by the wayfarer in the streets, such as that bit within the wards of the Tower, or the fragment at Saint Alphage London Wall which serves as a foundation for the houses that shut in the old churchyard of Saint Alphage. There is another bit at All Hallow’s in the Wall and another in the old Churchyard of Saint Giles Cripplegate.

Opposite the little church of Saint Mary le Strand is Strand Lane, a narrow passage leading down toward the River. Walk down about twenty paces till you see on your left a small wooden door in the stone wall of an old house. On that door in faded letters, you may read the legend “Roman Bath.” Push open the door and descend a flight of steps within till you come down to the Roman level and there you will find the only Roman bath to be seen today in London. It was a private bath belonging to a Roman villa that stood at a distance outside the walls. It is still supplied by a spring of clear cold water and until a few years ago, it was used by a club as a plunge bath. This private bath5 and the few fragments of the Roman wall are all that is left in position of the opulent city of Londinium Augusta.