Saxon and Dane

Of Saxon London, few traces are to be seen today except in the Museums. The Chapel of the Pyx together with adjoining parts in Westminster Abbey, remnants of the work Edward the Confessor executed in the Norman style, is almost the only preconquest edifice that I know in London. As for the Danes, you will find in the Guildhall Museum a single Danish tombstone, the only relic of the Danes that has ever been found in London.

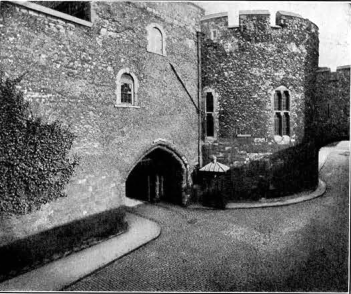

The Tower

The Normans however have left us enduring monuments, of which the most famous and the most imposing is the historic Tower. There was an ancient British fort, a Roman fort and afterwards a Saxon fort at the point where the Tower stands, but William the Conqueror built the Tower not as a fortress to defend London but as an argument to convince London and to confirm his authority over the City. William never felt quite secure in his new capital. He couldn’t forget that his invitation to be crowned carried with it certain reservations and conditions and that his tenure of the crown depended on his good behaviour for which he had given solemn pledges before his coronation.

William’s first official act as king was to confirm these pledges in a State document still preserved in the Guildhall. It is the shortest State document in existence, and is usually known as London’s first Charter. It is written on a strip of parchment about six inches long and an inch and a half broad. There are four and a fraction lines of text in the English language.

“William the King greets William the Bishop, and Gosfrith the Portreeve, and all the burghers within London, French and English, friendly; and be it known to you that it is my will that ye shall be possessed of all your rights according to the law as it was in King Edward’s day. And it is my will that every child shall be his father’s heir forever. And I will not endure that any man offer any wrong to you. God keep you.”

There is no mistaking the meaning of that, and it is perfectly clear that it was dictated by the Londoners themselves. I am convinced in fact that the language used is the language of that same Ansgar, sometime Sheriff of London, William’s Chief of State, who was carried from Hastings field on a stretcher. It simply confirms the ancient customs, rights and privileges of London as they had been hitherto observed. It is a more eloquent document than the later Magna Carta, often erroneously and extravagantly called the First Charter of English Liberties. So far as I can discover there never was a time when the Londoners did not have a distinct understanding with their rulers that they would do just about as they pleased, and so long as that understanding was faithfully observed on the part of the ruler they have ever been the staunchest of loyal subjects.

Image Number: 203619

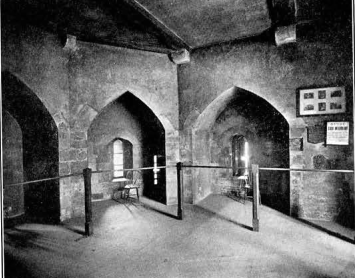

Let us return to William’s great keep. The Tower was first of all a Royal residence, a fortified castle which might protect the City or maintain itself against the City. Like other keeps it had accommodations for prisoners. It was enclosed by a wall with bastions and towers and surrounded by a moat. In the middle stands the great Keep called the White Tower, the core of the whole formidable plan, with its walls fifteen feet in thickness. The White Tower is used now as an armory and it contains also the Chapel of Saint John, the oldest church in London. Among the towers that encircle this Norman Keep one of the most interesting is Beauchamp Tower where famous prisoners left inscriptions carved on the walls. In the Wakefield Tower are kept the Royal Regalia. The crowns, scepters and swords of State do not include any that is of earlier date than Charles II. All the old Regalia of England, including the crown of Alfred, was taken from the Tower by the Commonwealth government shortly after the death of Charles I and destroyed. The Tower is English History. The heritage of its enduring walls is the sum of England’s tragedy during several centuries and the theme of her darkest story. But what excites my amazement when I read the history of the Tower is not the long list of distinguished names of its victims but the wonderful spirit that pervades the whole grim business. A queen, Katherine Howard, awaiting her execution at dawn, has a block brought into her room in the night to rehearse her part in the morning’s performance. Lady Jane Grey—sixteen, innocent, beautiful, accomplished, spent her last night writing a letter to the father whose ambitions had brought her to the scaffold. There could be no nobler document than that tender letter,—lines of cheer and comfort and not a tremor from beginning to end. A few days later that same father, the Duke of Suffolk, was himself brought to the block on Tower Hill. Carrying himself with great dignity and composure he addressed the crowd. He made no plea, no complaint, no attempt to exonerate himself, no charge of wrong or injustice, no repentance, no self pity. He had played and lost and that was all there was to it. He ended his speech by saying there would be some in the crowd who would feel like praying for him and he wished to thank them. Then occurred one of those little comedies with which men are so apt to mix their tragedies. A tradesman standing in front of the crowd spoke up and said,— “But Sir, how am I going to get the money that you owe me?” The Duke replied, “You come to me at an awkward time. I must refer you to my executors.” And as he laid his head on the block, who knows but his last sensation was a feeling of grim satisfaction that for once in his life he had evaded a creditor.

There were two scaffolds, one within the wards of the Tower on Tower Green and the other outside on Tower Hill. Most of the executions took place on Tower Hill, but Anne Boleyn, Lady Jane Grey, the Countess of Salisbury, Katherine Howard, the Earl of Essex were executed within the wards on Tower Green at a place that is marked by a plate in the pavement.

The Tower has been long neglected. No Sovereign has lived there since James I and for more than a hundred years no State prisoner passed within the gates till the World War. Then the old fortress must have been reminded of the days when the paths of Glory led straight to the Tower. About a score of the German spies were executed there, and one at least, Carl Lody, was brave for he conducted himself as well as even the traditions of the Tower could demand or as anyone could wish for in any enemy.

It is strange how the threads of history lead in that direction. Once in London it occurred to me to look up the home of William Penn. I had a vague notion that he was claimed by some place near London. I consulted the Dictionary of National Biography. I learned that he was born on Tower Hill next door to the Tower of London. He was baptized at All Hallows Barking, a step from the Tower. Then I came to Lincoln’s Inn where he lived and then back to the Tower itself which he also inhabited.

It is commonly supposed that the Tower is a gloomy place inhabited by ghosts and warranted to break the spirit of the strongest. It has never struck me as a gloomy place and why should ghosts be gloomy? No rents to pay and immunity from arrest. True there is the Tower’s tragedy but what human habitation has not known tragedy or what smiling field from Gettysburg to Gethsemane? To me the Tower has always seemed a cheerful place fit for a Royal residence. Of course Penn was a prisoner in the Tower, but so was Queen Elizabeth and it does not seem to have broken her spirit. It probably gave that demure Princess a dawning sense of her own importance. Doubtless it had the same effect on Penn. It was not thirteen years of the Tower that broke the heart of Raleigh, but unmerciful Disaster that followed his steps from the day he left the shelter of its walls. If he had stayed there writing history and making experiments, his life would have been longer and happier and the world would have been richer.

Domesday Book

Image Number: 22686

In Chancery Lane stands the Record Office where the State documents of England are kept on file. It is a most formidable and precious array of papers sacred to the uses of History. Among them are some very human documents and some that are very businesslike. There are Ancient Charters, Treaties, letters of Kings and Queens to each other and to their subjects. Letters of great subjects to their sovereigns. Records of State trials and most precious of all the Domesday Book. It is a record of the survey which William the Norman caused to be made of all the land in England, with its valuation, the names of the owners, together with the number of houses, cattle and other property. It was popularly called Domesday Book because the people said that what was written in it would hold good till Doomsday. From it there was no appeal and its aid is still sometimes invoked in the law courts. Just before the survey was finished, William during a visit to Normandy was killed by a fall from his horse. Domesday Book is written on parchment in Latin and in a beautiful clear script. An interesting thing about it is that London is omitted from the survey. The reason is not positively known but we may readily surmise that the Londoners said that they never kept Domesday Books and it wasn’t done. Formerly Domesday Book was kept in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey and was removed to its present quarters only in 1865. In the same place may be seen the old oaken chest in which it was formerly kept. The Record Office is on the site of the Rolls House and chapel, a building erected by Henry III in the 13th Century for converted Jews. As the number of converts diminished it was taken for the use of the Master of the Rolls. The site of the Chapel is now occupied by the Museum that preserves the dimensions and some parts of the old Chapel. In this Museum is exhibited the Domesday Book and some other documents of vivid interest.

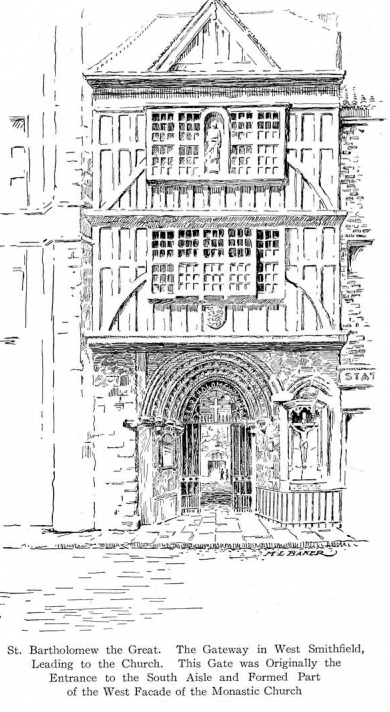

Saint Bartholomew the Great

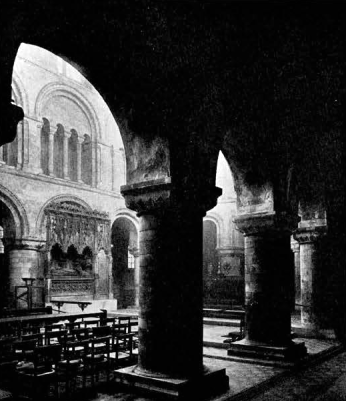

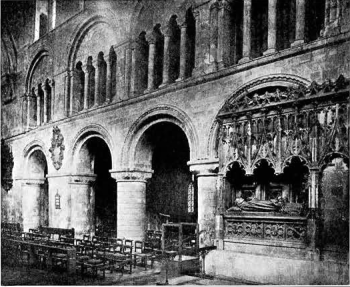

Next summer London will celebrate the eight hundredth anniversary of the founding of Saint Bartholomew the Great, the Church and the Hospital, both founded in 1123 by Rahere whose story sheds an interesting light on the times in which he lived. Accounts of his origin differ and the exact position which he came to occupy at the court of Henry I may not be entirely clear. The story that has as good a claim as any assigns to him a humble origin and avers that he improved his fortunes by his wits and by making fun for those who could reward a gift that gave them light entertainment. By these means he attained to the position of court jester and to considerable wealth. Then he became converted, gave up his gay life and made a pilgrimage to Rome. It happened that seven years earlier the bones of Saint Bartholomew were found in India, brought to Rome and deposited on an island in the Tiber where there had stood a shrine of Esculapius and there was a good deal of popular enthusiasm for the new relics. Accordingly when Rahere was taken sick at Rome he made a vow to Saint Bartholomew that in case of his recovery he would build a hospital in London. In a vision the saint appeared to him, accepted the vow and promised a return to health. In London afterwards Saint Bartholomew again appeared to Rahere who in his gratitude for health restored and a safe return allowed his benefactor to persuade him to build a regular religious establishment as well as a hospital. His businesslike visitor then pointed out to him that the heath outside the north wall of the City, the smooth field—Smithfield—was frequented and inhabited by a lot of grooms, horse dealers, jockeys, stable boys and the rough, heterogeneous and unclassified crowd that congregated near the horse fair. These people had no church and were without priests or religious discipline. Smithfield was therefore selected as the site of the hospital and the priory both of which Rahere set about building, the one close to the other but each established under a separate foundation. The priory was placed under the Canons of Saint Augustine to which order Rahere himself now belonged for he became the first Prior of Saint Bartholomew. On the tomb of Rahere, the founder, in the Church of Saint Bartholomew the Great his effigy may still be seen, attended by the figures of two kneeling monks with Bibles open at the 51st chapter of Isaiah, 3d verse.

“For the Lord shall comfort Zion: He will comfort all her waste places; and He will make her wilderness like Eden and her desert like the garden of the Lord; joy and gladness shall be found therein, thanksgiving and the voice of melody.”

All that remains of Rahere’s Priory is the choir of the Church. The Nave, together with the Cloisters and all of the conventual buildings were destroyed after the dissolution and the whole place

thereafter fell into neglect and decay. A forge was installed in the North Transept; a parochial school in the North Triforium and a Presbyterian Meeting House in the South Triforium behind Prior Bolton’s oriel window whence in the 14th Century he used to watch the celebration of Mass. The Lady Chapel was bought by Sir Richard Rich who used it as a dwelling house. Later it became the shop of Samuel Palmer, Printer, the shop in which Benjamin Franklin worked during his first visit to London. In the 19th Century the Lady Chapel became a fringe factory, but towards the end of that century it was reclaimed and since that time everything possible has been done and is being done to preserve all that remains of the old Monastic Church. The churchyard now occupies the ground that was formerly the Nave, the pavement of which is nearly five feet below the present level of the ground where the tombstones stand. The present front of the Church was built after the Nave was destroyed by Henry VIII and the narrow approach by which the entrance is reached was excavated through the graveyard in 1863. This approach leads from Smithfield by an ancient gateway that was originally a part of the west facade of the Church of which it formed the southwest entrance. Looking towards Smithfield this surviving fragment of the original church marks the position of its western front.

Next to the chapel in the Tower the Church of Saint Bartholomew is the oldest in London. It is one of the finest examples of Norman architecture to be seen in England.

The hospital just to the south of the Church was in charge of a Hospitalier assisted by eight brothers and four sisters subject to the Prior. Its good work has never been interrupted since the day of its foundation. There Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood, and lately it has been the refuge of the maimed in the war. Its service to Humanity is a long one. What it must have witnessed during the Black Death of 1348 and the Great Plague of 1665 is too appalling to think of, but I can picture the doctors of that day exposing themselves to infection in their heroic efforts and dying by hundreds. There was little medical science in 1665, and few safeguards. The people could only chalk crosses on their doors, while the dead carts rolled and the doctors watched the stars and dissected the bodies of the victims in their desperate efforts to learn something. One often hears the just praises of the doctors who in our own day, armed with science and with modern safeguards are making such a noble fight against disease. But something is to be said for the old doctors who with little science and no protection made the same old war on behalf of their fellow men.

“Yes when the crosses were chalked on the doors,

Yes when the terrible dead cart rolled,

Excellent courage our fathers bore,

Excellent heart had our fathers of old.”

It must not be forgotten that when the great plague arrived in 1665 London had already experienced three visitations in the same century and when the greatest scourge of all came upon them they were prompt to make regulations respecting it. In the orders issued by the Lord Mayor, every parish was provided with watchers, searchers, doctors and nurses, grave diggers and dead carts. Each infected house was isolated till it got so bad that isolation had no meaning. Each house where the plague had entered had to be marked with a red cross a foot long with the words, “Lord have mercy on us.” Moreover in each parish one or more citizens were sworn in as examiners whose duty it was to keep in close touch with the conditions within his parish and report the same to the Lord Mayor and Council. Anyone refusing to serve was sent to jail. The old hospitals like Saint Bartholomews were soon overcrowded and temporary ones were opened.

In that dreadful time, about 70,000 people, or one person out of every three, died of the plague in London. Yet somehow the food supply was kept up and all needful work was done. The finest description of the Plague is that by Defoe who at the age of five years survived it and lived to write more than his truthful story of the event of which he must have retained vivid impressions. There are also contemporary accounts, including that of Pepys, that of Evelyn, and that contained in the letters of John Allin. The following written by the Rev. Thomas Vincent is sufficiently vivid.

Now death rides triumphantly on his pale horse through our streets, and breaks into every house where any inhabitants are to be found. Now people fall as thick as the leaves in autumn when they are shaken by a mighty wind. Now there is a dismal solitude in London streets. Now shops are shut, people rare and very few that walk about, insomuch that the grass begins to spring up in some places; there is a deep silence in every street, especially within the walls. No prancing horses, no rattling coaches, no calling on customers nor offering wares, no London cries sounding in the ears. If any voice be heard it is the groans of dying persons breathing forth their last, and the funeral knells of them that are ready to be carried to their graves. Now shutting up of visited houses (there being so many) is at an end, and most of the well are mingled amongst the sick, which otherwise would have got no help. Now, in some places, where the people did generally stay, not one house in a hundred but what is affected: and in many houses half the family is swept away: in some, from the eldest to the youngest; few escape but with the death of one or two. Never did so many husbands and wives die together: never did so many parents carry their children with them to the grave, and go together into the same house under earth who had lived together in the same house upon it. Now the nights are too short to bury the dead: the whole day, though at so great a length is hardly sufficient to light the dead that fall thereon into their graves.

Smithfield

The Church of Saint Bartholomew the Great and Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital stand at Smithfield (originally Smoothfield) a site that has served for many uses and witnessed many extraordinary scenes. It was a level, grassy field where from 1150 till 1855 the principal horse and cattle market of London was held on certain days of the week. It was also a fair ground and a favourite resort for strolling players, acrobats, jugglers and mountebanks. It was the scene of many famous tournaments. In very early times it was also a place of public execution.

In 1381 there happened at Smithfield an event so dramatic and of such striking effect that it deserves more space than I can give to it. The King, Richard II, was a boy of fourteen, handsome, chivalrous and courageous. In that year the rebel Wat Tyler appeared with his uncouth rabble from Kent and Essex. It seems that London did not deem it worth while to shut its gates on a crowd of peasants who entered the City without resistance. Having committed depredations and having given an exhibition of mob violence during which a number of citizens lost their lives, they drew off to Smithfield to plan what they would do to the City that was apparently at their mercy. Their plan was to kill certain people, take the young king prisoner, exhibit him in different parts of the kingdom to terrorize the country and then put him to death. Still the city authorities had done nothing to deal with the situation. The King who was at the Tower rode to Smithfield to meet the rebel leader and learn his demands. With him were a band of courtiers and prominent citizens among whom was the Lord Mayor, Sir William Walworth. As he parleyed with the King, Wat Tyler grew insolent, whereupon the hot tempered Lord Mayor rushed upon him and struck him down with a blow of his sword. His followers, seeing their leader killed, raised a great outcry and began to string their bows. But the King, spurring forward alone and standing in his stirrups in front of the infuriated mob cried out— “Will you shoot your King? I will be your leader.” It was an inspiration. He then led them to an open field some distance away where he held them in parley till Walworth who had hastened into the City returned with a sufficient number of armed men to give him some show of support. Why hadn’t he done that before? The King then persuaded the rebels to go home and the peasants’ uprising was brought to an end. Thus by his presence of mind, his courage and his sense of the dramatic, Richard at the age of fourteen saved the City from the vengeance of the most outrageous and disorderly mob that London had ever known.

But more deeply engraved in history is the memory of the fires of Smithfield, for there the Stake was fixed and more than a hundred men and women, Protestant and Catholic, were burnt to death on that field for Religion’s sake from the reign of Henry IV to the reign of Mary Tudor. On the wall of Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital is a poor little plate half hidden recording the names of some of those who were burned in Mary’s reign. It is strange to think that the fires of Smithfield had a church on one hand and a hospital on the other. But the fires of Smithfield have burned themselves out whereas the Church and the Hospital, surviving from an earlier day, are still among the noblest sights in London.

On the corner house of Cock Lane there is a gilt figure of a naked boy marking the spot where the great fire of 1666 was stopped, just short of Smithfield, by blowing up some houses.

The Great Fire

Near the approach to London Bridge stands a tall column designed by Wren to commemorate the Great Fire. It is known as The Monument and though it has taken its permanent place among the topographical terms of London, like the Embankment or the Bank, its significance is overlooked. I suppose that if the Great Fire of 1666 had happened in ancient Babylon, or Jerusalem, or Rome, or in any mediaeval or modern city outside of England, its magnitude and its significance in human events would not be missed by the historian. But in the English histories it figures as a fire that burnt a lot of houses and was rather a good thing because it appears to have put a stop to the plague. I once had an idea that the Great Fire was a sort of providential intervention sent to cleanse the City from the plague, an event for which London had to be thankful. Having with great diligence and labour found out the facts for myself, I have now a very different view of the Great Fire. It was an unmitigated calamity. It was also the most overwhelming and disastrous conflagration in history. Antiquity presents no example on a scale so tremendous and no modern instance is to be mentioned in the same terms. The burning of Rome was of much less consequence. In the first week of September were destroyed the landmarks of a thousand years. The greatest and finest city of Europe was swallowed up in smoke and flame. Mediaeval castles, palaces and great houses by the hundred, hospitals, almshouses, libraries, the Halls of the City Companies—a hundred in all—markets, more than fourscore churches, one of the greatest mediaeval cathedrals in Europe, 13,200 houses, 640 streets, four of the seven City Gates, all the stores of merchandise, records, paintings, tapestries, furniture, and the accumulated treasures of centuries were completely burnt. There remained a fringe, mostly outside the walls, including the Tower, a part of the Temple, part of Smithfield with Saint Bartholomew’s Church and hospital, the Charterhouse and a few streets of houses. The fire began near where the Monument stands and at the end of a very hot and dry summer—the dreadful summer of the plague. It burst upon the City like a sudden storm. The upward rush of the heated atmosphere caused a great wind to blow and like a gale at sea, it lashed the flames into billows that rolled with incredible speed from river to wall and over the wall. Once more the Londoners fought for their City but the enemy was more swift and terrible than Saxon or Norman or Dane. The able-bodied men put themselves across the track of the fire. With the aid of gunpowder and with all the implements they could command, they opened broad lanes across the City. The fire jumped the open spaces they had made. Driven back and blowing up houses as they went, they worked through days and nights, and met defeat at every point till at last in the very outskirts they prevailed on two or three sections of the battle line. King Charles himself was among the fighters; his brother James, Duke of York, was one of the most active in organizing the work. Everyone worked; princes, noblemen, shopkeepers, artisans, labourers, sailors home from the sea; rich and poor together. They were defeated. For a week London was a furnace and then it was no more.

Meantime women and children and the older men were streaming out of the City. Some of them snatched what they could save, but there was little time for salvage and few means of transporting possessions. Countrymen swarmed towards the City with their carts and I am afraid we have it on good authority that some of these countrymen at great profit to themselves hired their carts to Londoners in their need. There have been profiteers always.

When it was over the population was living in shelters on Moor-fields and in the open country to the north of the City. Yet, within four years, more than ten thousand new houses had been built and in a few years more the City with its churches, halls, palaces and markets, and its great Cathedral had risen from its ashes. I know of no parallel to this rapid building of a city unless we may find it matched in the city building of the Romans. The new City was well built of brick and stone. No wooden buildings were permitted and the houses were substantial.

At a depth of several feet below the present pavements, relics of the fire are sometimes brought to light in the sinking of foundations. In 1910 there was found the entire contents of a jeweller’s shop, quite undamaged by the fire, a beautiful collection of exquisite seventeenth century jewellery, that may be seen in the London Museum. Who knows what treasures lie hidden under the streets and houses of modern London?

By a happy accident of Fate, a great architect was on hand. Immediately after the fire Sir Christopher Wren came forward with a comprehensive scheme for laying out London on a splendid new plan with broad highways and squares and Thames embankment and many architectural and ornamental features. The plan was approved by the government but the Londoners did not want a city on a new plan, they wanted the City they had known. They had their way for in the rebuilding of the houses, the streets were kept as they had been. But Wren left his mark on London in the astonishing number of houses and churches that he designed and that remain among the finest in the City till today. To crown his work he received a commission for rebuilding Saint Paul’s on the old site.

Saint Paul’s

Image Number: 22672

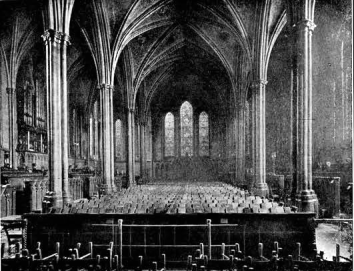

It was the traditional site of the Temple of Lud, worshipped by the Ancient Britons, and later of the Roman Temple of Diana. In the seventh century the Church of Saint Paul was founded by Ethelbert, for Mellitus the first Bishop of London. As an endowment the King gave the church the Manor of Tillingham in Essex and that Manor remains to this day the property of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. This seventh century church of Saint Paul’s was burnt down in the eleventh century when the Normans began to replace it by the great church known as Old Saint Paul’s destroyed by the Great Fire in 1666. Old Saint Paul’s was two hundred years in building. The generations of its builders saw the change from the Norman Style to the pointed or Early English Style and both were represented in the finished edifice. It was an immense cathedral that must have made an impression of vastness and grandeur more pronounced than anything seen in London since its time. It was at least a hundred feet longer and a hundred feet higher than the present Saint Paul’s. It had more open space about it. London was not so large, or so crowded with houses. The Cathedral must have dominated the whole City with superb and overwhelming effect. In time its great Nave came to be used for many public purposes not connected with religion. There the lawyers met their clients, each man of law standing by his pillar. All kinds of business was transacted amid a general uproar. There servants went to be hired. Falstaff claimed to have bought Bardolph in St. Paul’s. Gallants walked up and down in search of adventure or to learn the news.

Wren’s masterpiece of Portland Stone with its sombre mantle London fog spun by the winds, adds to the dignity of the ancient memories that are there enshrined together with the illustrious dead, for Nelson and Wellington are both buried in Saint Paul’s.

On the west front of the Cathedral are two towers; that on the north contains the peal of bells and in that on the south are hung the hour bell of the clock and the bell known as Great Paul. It weighs nearly twenty tons and is rung for five minutes at one o’clock on every day of the year, year in and year out. That is the far off booming sound that is heard in the City about one o’clock, and that seems to come from somewhere overhead. The great dome, lifted over the City crowding round it focuses the vision from all quarters of the compass, but great though it is, the Cathedral Church of London suffers by comparison with its mediaeval predecessor, Old St. Paul’s.

In an open space beside Saxon Saint Paul’s stood a bell tower and the ringing of that bell was a summons calling together the citizens of all classes for the public meetings of the Folkmote. In a

similar position beside the Norman Church of Old Saint Paul’s stood Paul’s Cross, a kind of open air pulpit surmounted by a large cross. To Paul’s Cross came on Sundays many orators, preachers, reformers and agitators of every description to express their opinions in public, to air their grievances, to expound some doctrine, to advertise some idea, to advocate some right, to plead some cause, to spread some news, to denounce the government and to harangue the patient London crowd. The King, the Court, the Church, the lawyers, the Nobility, the Capitalists were spoken of in terms adapted to the speakers’ sentiments and the sorrows of the poor were dwelt upon with much feeling. The windy corner of Hyde Park opposite the Marble Arch inherits the tradition of Paul’s Cross, for the Sunday orations in that expansive precinct are not very different from those that formerly fulminated from the older rallying ground. The right of free speech in relation to civil government and social institutions is as old as London. Only in religious feuds and during periods of bitter conflict was there a diminution of that right, and even then it was not suppressed. True they occasionally talked themselves into jail or to the gallows during these warlike episodes but they talked just the same.

Cheapside

From Saint Paul’s Churchyard to the Mansion House runs Cheapside in ancient times a market place. It was much broader than at present. The Guildhall marks its northern side as late as the 14th century. On the southern side, on the line of the present buildings, rose a stately row of shops, taverns and dwellings. In the middle of that broad street the marketmen had their booths or selds. In narrow lanes leading north and south various trades carried on their business. On the south side are Old Change, Fountain Court, Friday Street (where they sold fish on Friday), Bread Street, Bow Churchyard, Bow Lane, Crown Court, Queen Street, Bird in Hand Court. Then comes Bucklersbury where the apothecaries had their shops and after that Cheapside becomes the Poultry. On the north side are Foster Lane, Gutter Lane, Wood Street, Goldsmith’s Street opening out of Wood Street, Milk Street, Honey Lane, Freeman’s Court, Lawrence Lane, King Street, Ironmongers’ Lane. Then comes the Poultry. Cheapside may look modern but the moment you turn into any one of these wilful lanes and alleys that plunge at once into ancient London you leave all the modern world behind and lose yourself in the past, where if you wish to make youself at home, you may lodge at Williamson’s Hotel in Bow Lane, one of the ancient landmarks of London, under the shadow of Bow Church steeple.

Of all these side streets, lanes and courts the most famous is Wood Street named after a goldsmith of great renown (Sheriff in 1491). He built a beautiful row of houses known as Goldsmiths Row in Cheapside and contributed largely to the cost of building St. Peter’s Church at the foot of Wood Street. The Church is gone, but a part of the churchyard remains with a few tombstones and a single plane tree. The little Churchyard and the plane tree are shut off from Cheapside by two little shops only one story high for there is a clause in the ancient lease that the tree must be protected and in order that it may have plenty of light and air, the height of the houses must not be more than one storey.

The goldsmiths’ shops of Cheapside were reputed to be one of the great sights of London. They have long since moved elsewhere but Goldsmiths’ Hall still occupies its original site in the famous quarter. The Goldsmiths Company, one of the oldest of the City Guilds, owns and exercises the right of assaying and stamping every piece of gold and every piece of silver manufactured in London. All objects of gold and silver, as soon as they leave the workman’s hands, are sent to Goldsmiths Hall. A portion is there scraped from each article and passed to the Company’s assayers. If the article is found true to standard it is passed, if not, it is destroyed without compensation to the owner. The scrapings used in the assay belong to the Company but no profit is made. Each piece passed receives the Company’s stamp as follows. The sovereign’s head, a lion, a letter of the alphabet indicating the year of the sovereign’s reign. This stamp, applied in Goldsmiths Hall and nowhere else, has given rise to our word hallmark.

Besides this extraordinary privilege, the Goldsmiths Company has a still more remarkable right—The Trial of The Pyx. The Company has custody of the Pyx, the chest containing the standard pieces for testing the national coinage. All gold and silver coins issued from the mint are sent to Goldsmiths’ Hall, there to receive the official trial by a jury of the company. All coins of the realm after leaving the mint are tried by the Goldsmiths Company in their own Hall before they become current.

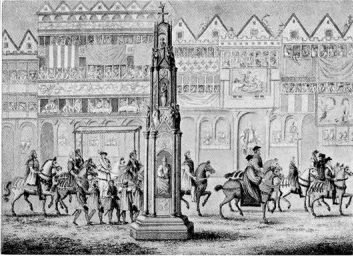

Four famous monuments stood in the middle of Cheapside. At the east end was the Great Conduit; the Little Conduit stood at the west end. They were supplied with sweet water conveyed underground by lead pipes from springs in Paddington. They were built in 1285 for the service of the City. On great days the water was turned off and the conduits flowed with wine instead for all who chose to drink. The third monument was Cheapside Cross, one of the twelve crosses erected by Edward I to the memory of his Queen Eleanor. Cheapside Cross stood opposite the end of Wood Street and may be seen in old engravings. It was damaged in 1441 and then rebuilt by the Lord Mayor. Later it was again damaged and rebuilt, but the Puritans regarded it as an idol and by order of Parliament it was demolished during the Commonwealth with other monuments that had given much pleasure to the Londoners.

There was also the Standard in Cheapside which appears to have stood opposite Bow Church in the middle of the Street, but what it was like I do not know. Beside it offenders against the law were punished by standing in the pillory and for great offenses were beheaded. It was also the place for burning false weights and measure and false merchandise.

The taverns of Cheapside were many and of joyful memory. A favourite sign for an ale house was a long rod projecting horizontally over the street with a bough or bush dangling at the end of it. Hence the proverb “Good ale needs no bush.” These signs attained such a length in Cheapside that they were restricted by law to seven feet. But Golden Cheapside was celebrated in other ways. It was the special scenic background of the mediaeval pageants on their way from the Tower to Westminster when its lavish decorations included gorgeous towers, triumphal arches and hangings of rich tapestry and cloth of gold. Cheapside was moreover the scene of many tournaments when the King and Court came to witness the glittering shows which they viewed from stands erected at Bow Church.

Image Number: 22687

If you will look up at the north front of Bow Church where it faces Cheapside you will see a little balcony projecting over the street below the tower. This feature was introduced by Wren when he rebuilt the Church after the fire to commemorate an old tradition. There had stood in front of the older Church a stone tower, “one fair building of stone called in record a seldam, or shed, which greatly darkeneth the said church; for by means thereof all the windows and doors on that side are stopped up.”6 This structure had been erected by Edward III as a stand from which he and his Queen and court could observe the tournaments. Eventually after many reigns this building passed into private hands and appears to have been converted into some kind of a tavern or place of entertainment called the King’s Head of which Stow tells the following story. In 1510 on St. John’s eve King Henry VIII, disguised as a yeoman of the guard and carrying a halberd over his shoulder, came to the King’s Head and there took his stand the whole night to see the procession of the City Watch. In the morning, when the Watch was done, he went home, none having recognized him. When St. Peter’s Eve came round in midsummer, Henry appeared riding in state with the Queen and court and all spent the night at the same place seeing the City Watch.

The procession of the City Watch like all great pageants passed through Cheapside and must have been a very splendid spectacle, but there were also the Royal Ridings which were the occasions of the richest display and costliest decorations. On Lord Mayor’s Day Cheapside was similarly decorated in honour of the Lord Mayor’s Show.

In Cheapside were born Saint Thomas a Becket ; the author of Paradise Lost was born in Bread Street, Cheapside, and the author of Utopia was born in Milk Street, Cheapside. Between Friday Street and Bread Street stood the Mermaid Tavern where Shakespeare and Raleigh and Ben Jonson and other friends used to meet to drink port wine and exchange the gossip of the day. In Cheapside today if you have letters of introduction you may gain admission to Goldsmiths Hall, Saddlers Hall, Mercers Hall, Grocers Hall and other famous halls of the City Companies. On the South side is old Bow Church with its graceful spire where Bow Bells call the Cockney home, for everyone born within sound of Bow Bells is a Cockney and however far he may wander he always hears the call of Bow Bells.

Image Number: 22687

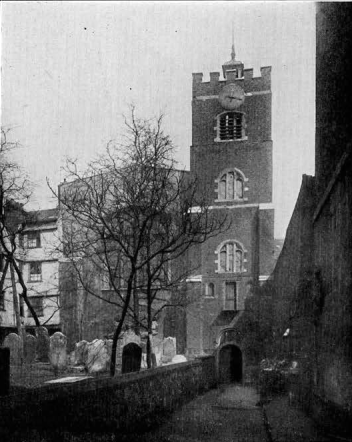

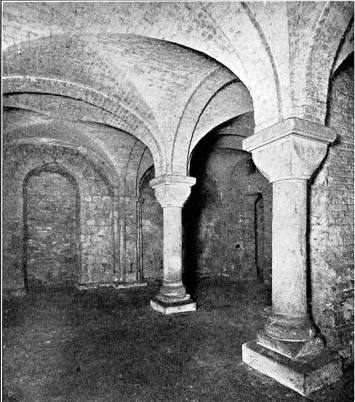

They have a friendly greeting for the stranger too, these ancient bells of Bow, for when Dick Whittington as a lad walked to London looking for a job, he was so overpowered by the busy life of the streets, that he turned his face towards home again. Walking along Cheapside he heard Bow Bells calling, “Turn again Whittington, Lord Mayor of London, turn again Whittington, Lord Mayor of London,” and he turned again and Bow Bells kept their promise after many days, for Dick Whittington became Lord Mayor of London, not once only, but four times. The bells are twelve in number and they hang in Wren’s most graceful spire, for the Church of Saint Mary le Bow was rebuilt after the great fire. It was founded before William the Conqueror, and its ancient Norman crypt survives.

That is Cheapside, celebrated by Chaucer and by Shakespeare and made famous also by that great Londoner, John Gilpin, in his memorable ride. For “the stones did clatter underneath as if Cheapside were mad.” This loquacious quality of London brick and stone, this familiar gossip of engaging ghosts, is one of the sweet influences that make the streets so habitable for us all. The bells have friendly tongues, and tavern doors repeat familiar legends and snatches of old song, and there are voices in the very stones that conjure us with hallowed music of the mother tongue.

The Temple

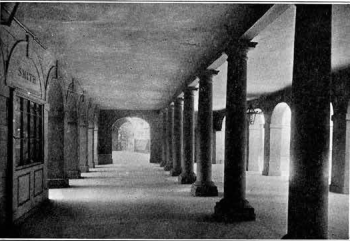

The Royal Courts of Justice occupy a new building on Fleet Street, erected on historic ground associated with legal traditions of London. On the opposite side of the busy street is Middle Temple Gate, an archway giving access to a passage that leads to the sacred precincts of the Temple. I have said that the streets are silent, but here, a hundred paces from the busy tide of traffic, we have penetrated to a stillness that makes our footsteps seem strangely loud and alarming. The air is hushed. In Fountain Court the water whispers softly and the very birds in the leafy overhead have tuned their little throats to the cloistered quietude that broods over the Middle and the Inner Temple, the Sanctuary where IT sits enshrined—the awful Majesty of the Law.

Image Number: 203642

The Temple was the seat of the Knights Templars, that famous order, half military and half religious, founded during the First Crusade, an order which spread throughout Europe, became rich and powerful and if we are to believe the charges brought against it at the time of its dissolution, very corrupt. The attack upon the order which became general on the Continent was not shared in England, but when the dissolution was pronounced by the Council of Vienna in 1312, the properties passed to the Knights Hospitaliers. In London however that Order did not take full possession of the Temple when the Knights Templars were disbanded. The three parts of the properties lying contiguous to each other were called the Inner, the Middle and the Outer Temple, according to the relation of each to the CITY. The Knights Hospitaliers were allowed to occupy the Inner, which included the more sacred parts. The Outer was granted by the King to the Bishop of Exeter and was eventually acquired by Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and with Essex House became the seat of that ill fated nobleman. There he surrendered to the officers of Elizabeth and thence he proceeded to his trial and execution. The properties continued in private hands and so the Outer Temple disappears except as a name and a location extending from the Strand to the River along both sides of Essex Street. Within a few years of their occupation of the Inner Temple the Knights Hospitaliers were in possession of the Middle as well and we find them renting parts of the Inner to a certain company of lawyers, and the Outer to another company of lawyers, the rent paid in each instance being ten pounds annually. It was therefore early in the fourteenth century that the lawyers got their first footing in the Temple and from the first they appear to have formed two distinct societies, one in the Inner Temple and the other in the Middle Temple. In the hands of these two societies the Temple became at once a seat of learning and of many pastimes besides the law. Young men were sent to the Temple to acquire the accomplishments that were befitting a-gentleman and necessary to a useful citizen, among which accomplishments music and dancing were prominent. Chaucer was a member of the Inner Temple and it is on record that he was there fined two shillings for beating a Franciscan Friar in Fleet Street. In the Canterbury Tales we have a description of a Manciple or Chief Cook of the Temple, one of the pilgrims going to Canterbury. From Chaucer to Lloyd George the Temple roll includes among the greatest in English History the names of Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake. The grounds, walks, alleys, stairways and chambers are haunted by the shades of men whose greatness fills the annals of England for the last six hundred years.

We are not to suppose that life in the Temple was one of routine for masters or students. We hear a great deal of revels at Christmas followed by masques, at both of which ladies were present and which were sometimes attended by the Court itself. These entertainments, lasting often all night, and the banquets that attended them were on such a gorgeous scale, with costumes so costly that only the very rich could participate. In the Halls of the Inner Temple the Masque and the. Miracle Play developed into the Stage Play under the direction of Christopher Hatton, the Dancing Chancellor, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth.

The Temple has not been spared the calamities that have been visited upon London. One occurred during the peasants’ revolt in 1381 under Wat Tyler. The peasants who regarded the lawyers with special aversion, moved in a mob to the Temple with the avowed purpose of hanging its inhabitants. The lawyers having got wind of the plan, had business elsewhere on that day. The rebels however plundered the houses, some of which they destroyed, and made a bonfire of all the books and records.

Till the dissolution, the Knights Hospitaliers remained the owners of the Temple, receiving rents from the two societies of lawyers. That Order was dissolved by Henry VIII, who confiscated the property and allowed the lawyers to remain as tenants of the Crown at an annual rental of ten pounds a year for each of the two societies. It seems that Henry had a scheme for turning out the lawyers and converting the Temple into some use of his own devising, but it also seems that the lawyers were too smart even for Henry and managed somehow to retain the properties at the same rent that they had been paying for over two hundred years, the only difference being that the Crown became their landlord. In 1608 James the First made an effort to deprive the lawyers of the premises by effecting a sale. Again they scored, this time by presenting the King with a gold cup weighing two hundred ounces filled with gold pieces in exchange for a charter granting them the Temple forever at the old annual rental of ten pounds a y ear for each Society. In 1673 however the two Societies together purchased these rents from Charles II and became the absolute owners forever, the one of the Inner Temple and the other of the Middle Temple.

Thus the Temple premises, the heritage of an ancient order of chivalry identified with the Crusades, became the permanent property of the lawyers who have been in continuous occupation since 1312, and whose present title is based on the rental of £10 which each of the two societies paid at that time for its share as tenant. In no instance does the persistence of custom in the City of London show to better advantage, with deeper meaning or with greater honour than in this Temple of the Law where students come from all over the British Empire to gain admission to the Bar. It exemplifies in itself the persistence of custom and precedent on which the English law is based and the equity that tempers the practise of the English Courts. The students and the barristers living in the Temple cannot fail to draw from its associations a sense of the dignity and enduring justice that stamp the heritage of the Bar. Breathing its atmosphere they become a part of its tradition.

Always there have been four Inns of Court—the Middle Temple, the Inner Temple, Lincoln’s Inn and Gray’s Inn, the last two lying outside the Temple precincts in Holborn. Each has its own independent organization but the four are in close affiliation and on absolute equality. They are the only power in England that can admit to the Bar. Clifford’s Inn on the north side of Fleet Street in Chancery Lane, Clement’s Inn, Strand, and Staple Inn, Holborn, were Inns of Chancery7 formerly associated with the Inns of Court, to which they stood in the relation of preparatory schools. The Inns of Chancery have no longer any functions and their buildings are devoted to other uses. The members of an Inn of Court are Benchers, Barristers and Students. The Benchers are the senior members, charged with the government of the Inn, the admission of students, the call to the Bar and the discipline of members. Each student must eat a certain number of dinners each term in Hall. Until the summer of 1921 the dinner hour remained fixed at 5.30 and was then changed to 6.30 as a concession to modern innovations. At the appointed hour precisely, an official called the panyer man, in livery walks round the Courts, blowing an ancient ivory horn mounted in silver. The benchers, barristers and students then assemble in the Hall and dine together. Nothing can excuse a student from attending this discipline.

Grand Days are functions held four times a year, once in each term, when judges and distinguished guests sit with the benchers in State at the High Table, separated from the barristers and students. The Readers Feast is a function held at regular intervals, when extra wine and extra commons are served.

The ancient revels presided over by the Lord of Misrule are represented today by balls, concerts, garden parties and other entertainments. Plays are given occasionally in the Hall where Shakespeare gave a first performance of Twelfth Night but the Masque of Flowers perpetuated until recently in an annual Flower Show of the Horticultural Society held in the Temple Gardens but now moved to Chelsea Hospital Grounds, has deserted the Temple Precincts altogether.

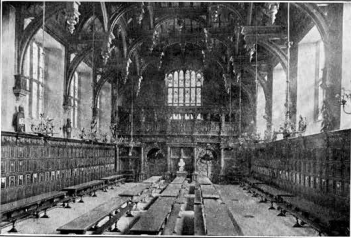

When in King Henry IV, Prince Hal said to Falstaff, “Jack we meet tomorrow in the Temple Hall,” he meant the Middle Temple Hall, one of the noblest edifices to be seen today in or out of the Temple. It was built in the early sixteenth century, and although the outside was refaced in the eighteenth, the interior remains unchanged with its fine old roof of oak timbers, its carvings and its stained glass windows. A venerable Hall where Fame in its mellowest and most reminiscent mood fills the obscurity of each dim recess and sits in splendour at each festive board—boards hewn from the timbers of the Golden Hinde. It was in this Hall that Shakespeare gave a performance of Twelfth Night in the presence of Queen Elizabeth.

The floor of Middle Temple Hall was renewed in 1730 and when the old worn out boards were removed we are informed that about one hundred sets of ivory dice, dark with age, were recovered from the retirement in which they lay since they had fallen through the chinks. Another strange discovery was made in 1894 when the walls were being wired for electric lights. Concealed in a closed recess near the roof was found a box containing a well preserved skeleton that must have been lying there for about two hundred years. How it came to be in that position we may leave the lawyers to decide.

In the Temple Cloisters, I saw one day a low square window with small panes looking toward Pump Court, and above the window in large letters the one word SMITH. There was no further information and no sign of a door. A search however revealed in a narrow alley leading from the cloisters a small wooden door like a secret entrance to a smuggler’s hold. This being the only entrance visible, I plucked up courage to knock, for though not aware that I had any business with the tenant, I had great curiosity. I was received very courteously by the occupant of that tiny tenement with its mysterious window. It was the queerest little shop I have ever seen, the shop of a wigmaker, the successor of a long line of barber wigmakers among whom have been some well known characters. Lord Chancellor Campbell in his Lives of the Chief Justices relates how Dick Danby, tenant of that shop, in his day used to cut his hair, make his wigs and aid him at all times with his valuable advice. There is another wigmaker in the Temple with another long line of distinguished predecessors, Albin whose little window looks on Essex Court.

The Temple Church was built by the Knights Templars in the twelfth century. It is the third ‘oldest church in London and in it the Knights Templars were accused of performing some very strange Pagan rites. In the Great Fire of 1666 the Temple Church barely escaped. The Duke of York with a volunteer force was fighting the fire in this quarter trying to save the Temple whole, but they were driven back and back till they were within the Temple precincts. Then the Duke, as a last desperate resort, decided to blow up some of the Temple buildings themselves to save the rest. The story is quite simply told by that remarkable person who has bequeathed to posterity the name of Samuel Pepys and his diaries. While the Duke was engaged in the hurried work of bringing in the gunpowder by which he was to make his last resistance to the flames, one of the lawyers accosted him and informed him that it was against the rules to bring gunpowder into the Temple. The Duke’s equerry, who was with him at the time, took the lawyer and beat him with a stick till he saw the force of the argument. The Temple buildings most exposed to the fire were blown up and the rest were saved. At one moment the Church seemed doomed. A great firebrand carried by the wind, fell on the roof and clung there, melting the lead and quickly burning through to the wooden timbers of the roof. A sailor among the Duke’s volunteers somehow climbed up on the roof and beat out the fire with his hands. Afterwards the Corporation of the City of London voted that sailor an award of fifty pounds.

The Temple has close historical associations with the American Republic. Five of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were members of the Middle Temple: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Hayward, Thomas McKean, Thomas Lynch and Arthur Middleton. Besides these, George Rutledge, William Livingstone, John Dickinson of Pennsylvania and Arthur Lee of Virginia and Payton Randolph, President of the Continental Congress of Philadelphia, were all members of the Inn.

London and the Colonies

London had a special stake in the colonies. It was linked through its trade, by the investments of its citizens and it was linked through the colonists themselves, many of whom came from London or had connections therein. In the earliest ventures overseas its merchants had an active interest. The voyages of discovery and plantation appealed to their trading instincts, for the possibilities of commerce were well known to them. Even the spoils of conquest were scarcely less alluring in their eyes. When Francis Drake returned from his voyage round the world loaded with plunder of Spanish possessions, he sailed up the Thames and anchored below London Bridge and London caught a glimpse of that astounding Argosy and its incredible captain. Queen Elizabeth in her gorgeous barge of State went in splendour to visit the great Adventurer. Drake was dined by the lawyers at the Temple where his name was already enrolled, and the taverns of Southwark and Fleet Street and Holborn and Cheape buzzed with the epic happenings and with healths to Francis Drake. Raleigh was at the Court, Shakespeare was getting ready to come to London, and all three, the Sailor, the Statesman and the Poet, must have met in the years that followed when men’s minds were still moved by that new vision of the earth encompassed and its treasures brought to London Dock. How these events must have stirred the emotions of him whose passionate love of England thrills even the cold audiences of today. Incredible far off days! In such a conjunction of the stars were the colonies conceived amid signs and wonders. I know of no event that presaged the founding of the Empire overseas like the arrival of the Golden Hinde at London. It was the most colossal and most daring propaganda that ever encompassed the earth. Westward Ho!

From that time on the Londoners developed and fostered the colonizing spirit and from the time that Englishmen got a foothold in America the plantations were nourished and powerfully supported by London merchants. Virginia was founded by the City of London and the City Companies together. Moreover the settlers who had been born in London carried with them overseas the London outlook. They brought with them their old attitude towards the State, transplanting the long familiar London posture of one who stands on guard, of one who knows to a hair the boundary line between his private domain and the domain of public authority. The definition of his rights that the Londoner continued to assert could not be challenged in Virginia, in Pennsylvania or in New England any more than it could be challenged in the Temple or in Cheapside. The ideas that had shaped the City’s history remained a strong link between it and the new Commonwealths of the West. Among the leaders in the New World were men learned in the law who had lived at the Inns of Court and sat with the Benchers in the Temple. Not the law alone but the customs, the traditions, the faiths of London penetrated the Thirteen Colonies.

In the reign of George III, London’s political power happened to be at the ebb. If the CITY had been in this trying time the arbiter of political destinies as it was before and as it has been since, the concessions made to the colonies by the government would not have stopped short of complete satisfaction of all their demands. Indeed if London had been in a position to assert itself strongly it is probable that no taxes ever would have been imposed. Certain it is that the unwilling country never would have been led into a war, feebly prosecuted to an issue determined in the end by a sentiment and a conviction that from the beginning found unanimous expression in London. Whatever difference of opinion there might have been in the colonies about the policies of the government there was none in London. Right or wrong these policies were opposed by the Londoners from the beginning. They refused to contribute to the cost of the war. The Lord Mayor and Aldermen, as spokesmen for the CITY, sent one remonstrance after another to the King on the throne till, incensed at their persistence, he informed their representative in Parliament that he would receive on the throne no more communications from the Lord Mayor. This was a denial of one of London’s ancient rights. The Lord Mayor promptly reminded him that London’s right of making representations to the King on the throne had never been challenged. The King acknowledged the right. The Lord Mayor and Aldermen continued to send their remonstrances against the colonial policy of the government. They were no perfunctory warnings that the CITY sent to the throne. The feelings of the Londoners were deeply involved and they were running true to their traditions.

“We lament the blood that has been already shed; we deplore the fate of those brave men who are devoted to hazard their lives—not against the enemies of the British name, but against the friends of the prosperity and glory of Great Britain; we feel for the honour of the British arms, sullied—not by the misbehaviour cf those who bore them, but by the misconduct of the Ministers who employed them, for the oppression of their fellow-subjects; we are alarmed at the immediate, insupportable expense and the probable consequences of a war which, we are convinced, originates in violence and injustice, and must end in ruin.”

Then France entered the war and Spain followed France. This was a bitter dose for the Londoners. They were well aware that the occasion of the taxes that the government sought to impose on the colonists was the cost of the wars in which England had been involved to protect the colonies and the overseas subjects from French aggressions. Yet the Londoners had made it known that they regarded the tax as unwarranted and unjust. They had made it clear that they were prepared to uphold on behalf of the colonists all that they had ever claimed on behalf of themselves. And now the colonies for whose preservation they had gladly paid and for whom they were prepared to fight, made common cause with the old opponents, the rivals of England on American soil for colonial claims. The Londoners found themselves in a difficult position. They had been let down. Their protestations were no longer possible. It was war with France. Their interest in the issue died. It was humiliating either way. Their support of the war was without heart and without purpose.

Many of the colonists as I have said were Londoners. Among the leaders were men who had been educated in that great training school of good citizenship, the Temple. London therefore understood quite clearly the meaning of the American contention, but the Declaration of Independence and French intervention were events that did not march with their traditions or harmonize with that clear understanding. They could not go along with their children in that new undertaking and in that association. As for kings and governments, they had elected their kings, they had deposed their kings, they had seen their King beheaded, which they knew was a bad business not to their taste. They had overthrown governments, made and unmade parliaments. They were prepared to reenact the events of history if necessary. They had done many things and were prepared to do more, but they had never been disloyal to England. Never. That was their limit. Now they must part company with the colonies. . . . So the colonies went their way—and then within a century and half came the first World War and threatened chaos. The two events are linked as the hole in the dyke is linked with the flood that drowns the land. But in both events London stood exactly where we would expect London to stand.