In ancient times and for long thereafter the invention of glass was accredited to the Phoenicians. As Pliny tells the tale, the invention was merest accident. Although the most adventurous of ancient seafarers, the Phœnicians liked to hug the shore whenever possible. One day a ship, laden with blocks of soda, landed its crew on a strip of sandy beach at the mouth of the river Belus. Like all good campers the men hunted about for stones to make a fireplace on which to rest their cooking pots, and finding none used some pieces of soda from the cargo. In the heat of the fire some of the soda melted, and combining with the sand made a clear bright trickle,—the first glass. It is perhaps obvious that an ordinary camp fire could never have melted soda and sand, but considerable excavation was needed to dispel “the Phœnician mirage.” No glass seems to have been made in Phoenicia before the fifth century B.C., but in Egypt glass jars were in general use as early as 1500 B.C.,—to say nothing of the vitreous glaze that was used in pre-dynastic times. So that evidently Egypt is the land where the industry first began. The Egyptians moulded their glass, for the blow pipe was unknown; the men blowing long tubes on the reliefs at Beni Hasan are really blowing their fires for smelting gold and other metals. Tradition makes the Romans the inventors of the blow pipe, but probably the Greek Orient is the place where was made in the first century B.C. the invention which revolutionized the industry.

Museum Object Numbers: MS5488, MS5489

In the spring of 1916, through the gift of Miss Lydia Thompson Morris, the University Museum received a collection of ancient glass now known as the John Thompson Morris Collection of Roman Glass, a memorial to the donor’s brother. This collection has been for some time on exhibition in the west room of the Mediterranean Section in Cases XI and XIV. It consists of one hundred and eighty pieces exclusive of beads and fragments. Gathered by Mr. Morris and his sister in Egypt, Greece and elsewhere through a period of years, it is an admirable supplement to the collections previously acquired by the Museum. The glass ranges in date from the fifth century B.C. to the fourth century A.D. or later, but the bulk of it may be dated in the first century before and the first century after the Christian Era. The earliest specimens are two “primitives” (Fig. 60). Such vases were moulded on a core; the threads of white were laid over the shape while it was still soft, and were dragged into patterns with a comb ; then the surface was rubbed smooth. The most individualized late ware is the so-called Jewish glass, made in Palestine in the fourth century of our era. Probably the most remarkable vase of this variety in the Museum is a pitcher of reddish glass (Fig. 61) with a flecked surface and orange iridescence; the body is hexagonal, each panel being decorated with a symbolic design, palm branches, the “temple door,” etc.

The collection is particularly valuable for showing both clear and iridescent glass. Collectors of Roman glass always look for iridescence, but the Romans themselves never knew it, because it has been added to the glass by the decomposing action of the earth in which it has lain buried for hundreds of years. Wen such glass is first excavated it frequently is covered with a dull, almost black coating, which, as it flakes off, reveals the iridescence. (Fig. 63, No. 2.) Ancient glass found in countries where there is a considerable rainfall always displays iridescence, but such pieces as are recovered from the dry sands of Egypt never display this quality. On the contrary, except for slight cloudiness, they appear exactly as they were when in use long ago.

This is not to indicate that ancient glass was made without colour. Most of the glass in this collection is basically blue, in tones ranging from a light shade through turquoise to dark blue; again, some specimens are violet or various shades of red. Such colours were dissolved in the mixture of quartz pebbles and alkali from wood ashes of which the glass was made. After the glass was fused it was left to cool in an earthen pan, which, when the mixture should be cold, could be broken away leaving a mass of glass clear at the bottom, with all impurities at the top. This scum could then be chipped off, and lumps of clear coloured glass were left ready to be softened by heat into a malleable condition. Such a lump of varicoloured glass is to be found in the John Thompson Morris Collection (Fig. 62). When the Romans had invented the blow pipe, glass was of course melted, but even then the feet and handles of vases were moulded and added by hand.

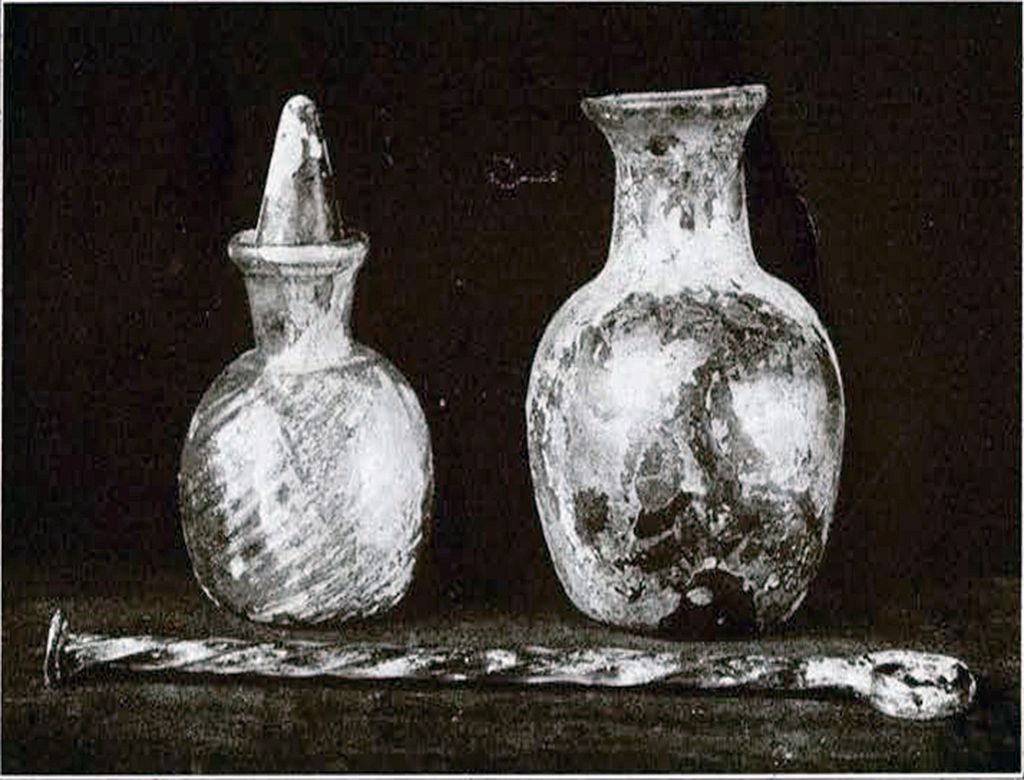

Museum Object Numbers: unknown / unknown / MS5597

There is now at least considerable variety in the tones of any one colour so that even if a number of vases are made of one and the same colour there is no monotony about them. Sometimes one colour is used for the body. and another for handles, or again threads of one colour or another were laid on a vase, or cross sections of threads were combined in a mosaic pattern. But the shifting patches of brilliant colour, varying infinitely in changing lights are due to the accident of time which turns the pale blue to turquoise and adds opalescent or fiery glints to the original colour. Some of the most beautiful iridescence is to be seen in Case XI.

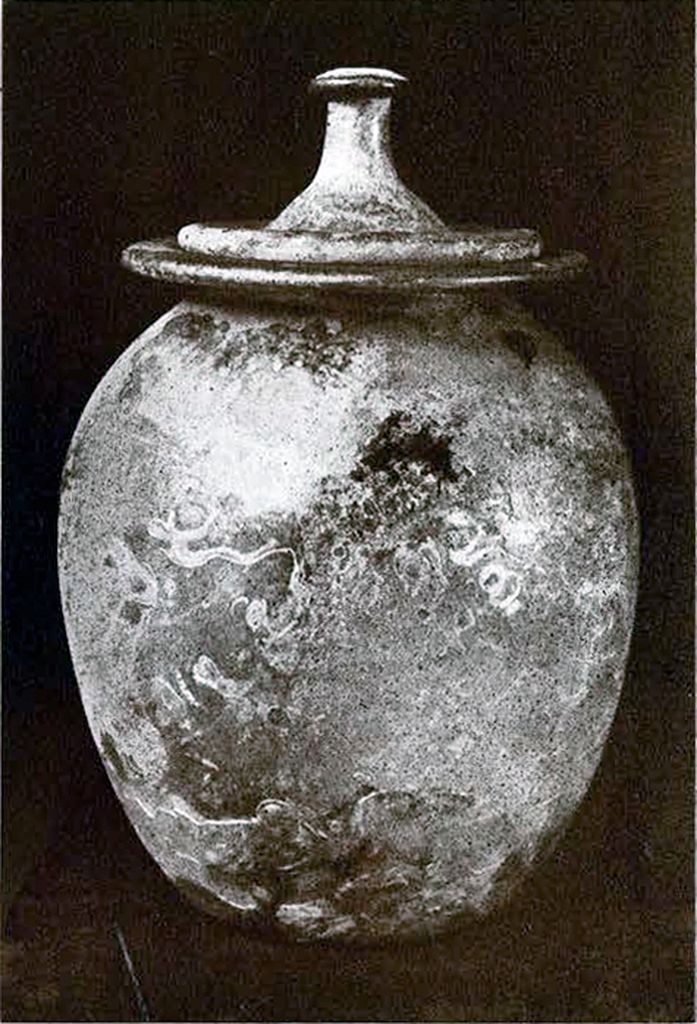

Museum Object Number: MS5553A/B

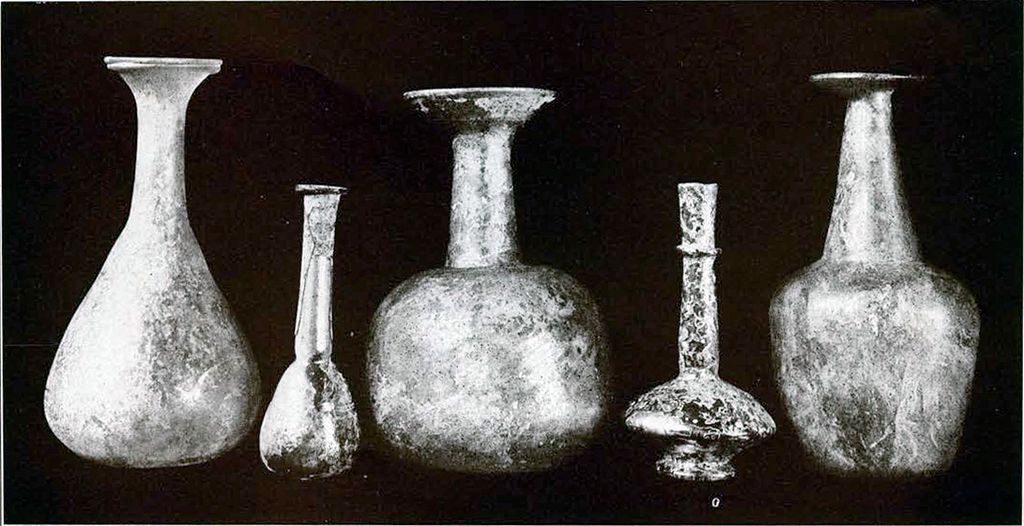

Much of the glass is in the form of vases, but there are a few beads and bracelets. Their preservation is due to their having been deposited in tombs, goblets and bowls by way of garnishing the feasts of the dead, perfume flasks and baubles to keep beyond the grave the beauty which was milady’s glory in life. The shapes employed are for the most part long-necked flasks (Fig. 69) of varying proportions and pitchers large and small. Of these the majority seem to have been used as containers of perfumes and oils for the toilet. Several vases are, however, of shapes quite different from any hitherto owned by the Museum. The prize piece is a large covered jar (Fig. 64) of very pleasing profile and delicate colouration, which was used as a receptacle for the ashes of the deceased in whose tomb it was found. There are also three “fillers,” each a different shape and colour (Fig. 65). One approaches the shape of a bird, and is thought to have served as a child’s feeding bottle. One small perfume flask has its stopper still in place (Fig. 63). There are also a number of small bowls of varying shapes and colours, one of which made of translucent glass has in the centre of its interior a hump like that of the Greek phiale mesomphalos (Fig. 66). One curious moulded piece is a plaque of dark green glass decorated with a head of Medusa full front in relief (Fig. 68). This was probably used as a medallion on the side of a very large glass vessel.

Generally the glass was made transparent, but sometimes opaque glass is found. Two small bowls, one red and the other white, afford an idea of the variety attained in this sort of work.

It is unfortunately true that some of the ancient glass is ugly, particularly when handles are added, for often the handles being moulded and added by hand to a blown shape, are crude and heavy. But the unpleasing specimens are relatively few, and serve admirably to accentuate the beauty of the others whose delicacy of colour and grace of shape make them of great interest both to students of antiquity and to modern craftsmen. Tiffany glass is inspired by ancient glass; and potters besides makers of glass may readily find in this product of the Egyptians and Romans their inspiration as well as their despair.

E.F.R.

Museum Object Numbers: MS5554 / MS5555

Museum Object Numbers: unknown / unknown / MS5543

Museum Object Number: MS5656A

FIG. 70.

Museum Object Numbers: MS5548 / MS5519 / MS5550

Image Number: 3569