The Museum is about to open a new exhibition of African and South Pacific Art and the time is appropriate to look for the motives that underlie these products. The exhibition will be more intelligible and interesting if seen in connection with the following related facts. In the present article I confine myself to the group of African wooden fetish figures. In another article I propose to treat of some other features of the exhibition.

Museum Object Number: AF5119

Image Number: 775

Museum Object Number: AF1346

Image Number: 759

The carved wooden figures of human beings and animals which are so typical of the art of equatorial Africa, especially in the interior and the west, are commonly grouped under the name of fetishes. This term, anglicized from a Portuguese word which was early applied in this sense, meant originally an amulet or charm. It has since been used to denote a wide variety of magical and religious objects, and fetishism has become a word to cover many diverse religious notions and practices of the African Negro and of other peoples who are held to be at a similar stage of development of mental or spiritual culture.

The great majority of these wood carvings undoubtedly have some connection with the religious usages of the Negro. In Africa, no less than in other parts of the world, religion has been the inspiration of art, or it might perhaps be truer to say that each has inspired and encouraged the other in the highest development to which the capacities of the race were able to bring them. If this is true, we might expect to find that the greater the hold religion has on a people (given the average aesthetic feeling in which primitive people are certainly not lacking) the more developed will be their art. In the southwestern Congo region the Bakuba-Baluba peoples have been characterized by a writer who has observed the Negro in Africa with sympathy and understanding as “singularly superstitious.” The choice of the epithet is perhaps unfortunate, the context shows that these groups of Bantuized Negroes have a more highly developed system of cults, religious or magico-religious, than any other Congo people of their degree of culture, which is high—for the Congo. And it is here too that we find the best and least contaminated Negro art.

Varied as are the practices connected with the use of “fetishes,” and numerous and undefined as are the religious concepts which give rise to them, it is possible to distinguish two notions as to man’s relations towards things seen and unseen, and the way in which he can control or influence them or they him, and as to the nature of forces powerful to affect destiny or give effect to desire. Here is a Negro’s exposition of what he believed concerning his own spiritual nature: “I have two things—one the thing that becomes a spirit when I die, the other the spirit of the body and dies with it.”

According to the Bavili of the coast region north of the mouth of the Congo, a man’s shadow, xi dundu, enters and leaves the body by way of the mouth, being thus associated with the breath, muvu. A dead man has no shadow even as he has no breath. The shadow is thus a vital element, but it is associated with mortality: it dies with the man. When a person swoons, it is because his xi dundu has been stolen by a sorcerer; if it is not returned, death ensues. Xi dundu is, evidently, a concept of the same nature as the “spirit of the body” referred to above. It can hardly be called a spirit in any modern sense of the term. It is only spiritual in that older sense which survives in such expressions as “animal spirits,” “high spirits,” an immaterial principle governing vital phenomena.

To the mind of the Negro every object in nature, inanimate as well as animate, embodies some such principle as this, and is endowed with personality or “self-power.” A description of the ceremonies which accompany the death of a chief of the Banziri of the northwestern part of the Mubangi valley gives the following suggestive details: “The relatives arrange the corpse in a doubled-up position on a kind of gridiron of poles. Then they kindle a fire under the body. Receptacles of baked earth are placed so as to collect the melted fat which trickles from the body under the action of the fire. Those who are present smear faces and hands with this fat, rinse it off with warm water, and these rinsings are drained into vessels and drunk by the relatives, who believe that in this way they incorporate in themselves the virtues and qualities of the deceased.” A chief has, of course, personality or self-power in the highest degree. He is preëminently the able man. Hence the ceremony.

Image Number: 4112

In the Delagoa territory there is a mole which burrows under the sand just below the surface. Children in that country are attacked by a parasite which lodges under the skin and burrows there in a similar way, so that the traces of its course are plainly visible on the surface. The women of the region make bracelets of the skin of the mole, which they put on the arms of their babies to protect them from the burrowing parasite. The mole-skin embodies the “virtue” by which one (the bigger and hence more powerful) burrower can defeat and drive away another.

In the Kasai-Sankuru region of the southwestern Congo, diviners make use of a particular apparatus. It consists of a wooden figure, usually of some animal, dog or crocodile, the back of which is flattened and smoothed. When it is desired to discover, for instance, the name of a thief, this flat space is dampened with a viscous liquid, and a wooden disc passed back and forth along it, the operator pressing hard upon the disc and reciting the names of the villagers. When the disc sticks, the name then being spoken is that of the guilty party. Here again, a principle inherent in the object may be used to supply the place of powers lacking in oneself.

It would seem that we have in such cases evidence of a concept of a principle of power inherent in men, animals, and inanimate nature, by which one may enhance and fortify his capacity for dealing with situations intractable to his own unaided forces. This concept is applicable to most cases of fetishism of the simplest kind, in which “powerful” objects are employed as charms, amulets, talismans and such “oracles” as that described above, as well as all objects regarded as “medicine,” preventive or curative.

The essential part of the fetish—the claw of a beast (Fig. 11), some other part of the body of animal or man, dried and powdered, leaves forming a concretion with resin or clay—is placed in a suitable receptacle such as the horn of an antelope, a small shell, or a hole made for the purpose in a figure, usually wooden, representing a human being or an animal. Any object —a stone, a stick, a tree—which attracts attention by some peculiarity of form or of imagined behavior may become a fetish; as when a Negro, stepping out of his hut to start on a journey, stumbles over a stone which flies up and strikes his leg, picks up the pebble, saying, “Ad, there you are!” and carries it off with him, firmly persuaded that it has acted thus in order to attract his attention and signify its ability to help him in the purpose for which the journey is undertaken. But we are concerned here with receptacles for “powerful” substances, which have the forms of animals, especially of human beings.

The projection of an invisible force to act at a distance on some other object—as when nails driven into a wooden figure of a man cause the death of the person whom the figure represents—would easily give rise to the notion that this force was a spirit. The container or fetish figure inhabited by it, especially if this had human form, would be looked upon in time as essentially one with the indwelling spirit, just as a man’s spirit or soul forms a unity with his body. Thus we get a second class of fetishes corresponding to the more developed religious ideas among the Negroes; fetishes of the first class continuing to exist at the same time, as a survival from a simpler day and an uncontaminated culture.

As fetishism developed and became more and more systematized, the ritual practices connected with it became so numerous as to require the services of a special class of persons skilled in the songs, dances, incantations, auguries, and offerings which came to accompany fetish worship. Hence the medicine man, witch doctor, magic doctor, whose baleful power, sometimes united in the same person with that of a chief, is still so strong in Africa. Such worship, including sacrifices to the fetish figures, is directed mainly to causing the fetish to exercise its powers for the advantage of the worshipers. It has grown out of and only partially replaced much simpler practices having the same purpose in which it is difficult to find any trace of the awe or reverence characteristic of worship proper.

Since the Negro tends to endow all objects, lifeless or not, with personality similar to his own, it is not surprising to find that he employs, to call forth from the fetish a beneficent activity, means similar to those he has found effective in the case of human friends, enemies, or persons in authority. Thus a fetish is petted, cajoled, or beaten. “The Negro in Guinea beats his fetish if his wishes are frustrated, and hides it in his waist-cloth when he is about to do something of which he is ashamed.” In this latter case, where it is attempted to conceal knowledge of a shameful act from the fetish, there is present the feeling of fear, which is at least an ingredient of awe, and shame, which belongs to a higher order of the same emotions; while fetishes of more important rank are “prayed to, talked to, sacrificed to, as sentient and willing personifications of the spirit” dwelling in the fetish. The squirting of the juice from a quid of kola in the mouth over the fetish figure is a common means of “refreshing” a personal or family fetish in which we may see, perhaps, the germ of the sacrifices offered to more important ones.

Image Number: 4111

Museum Object Number: AF1333

Image Number: 755

All the figures, illustrated here, from collections in the University Museum, are fetishes of one kind or another. Fig. 12, a so-called “nail fetish,” is from the Congo coast region near Luango. The custom of driving nails into a fetish is the expression of several different ideas as to the results expected. In one well-authenticated instance “a native . . . being accused of stealing . . . invoked the curse of death upon himself if he were guilty, and knocked a nail into his nkisi (fetish) as a proof of his good faith. At that time he was hale and well built, but soon grew meager and thin, and in three months he was scarcely recognizable. At last he came to the [missionary] and asked him to pray to God on his account, for he had stolen the things and would die if God did not forgive him.” The nail driven into the fetish is a means of calling house- or lares-fetishes to witness the validity of an oath; incidentally, the instance shows the extraordinarily powerful influence of even a divided faith upon the mind of a primitive believer.

The nails may be the record of the number of persons done to death under the power of that particular fetish. For every nail driven into the figure, the person against whom its power is directed will be afflicted with some disease, or may be at once stricken with death. This recalls the European witchcraft custom of sticking pins into a wax model of the person intended to be injured.

Again the nails may be of the nature of a spur, a kind of pointed incentive to the fetish to perform the functions expected of it. Fetishes treated in this manner are usually family- or lares-fetishes, which, in the Congo if not in West Africa, are often treated with remarkable roughness—may be beaten, thrown into the water or the bush. If a tutelary fetish shows itself more accommodating as a result of such treatment, it is restored to its place as guardian of the home.

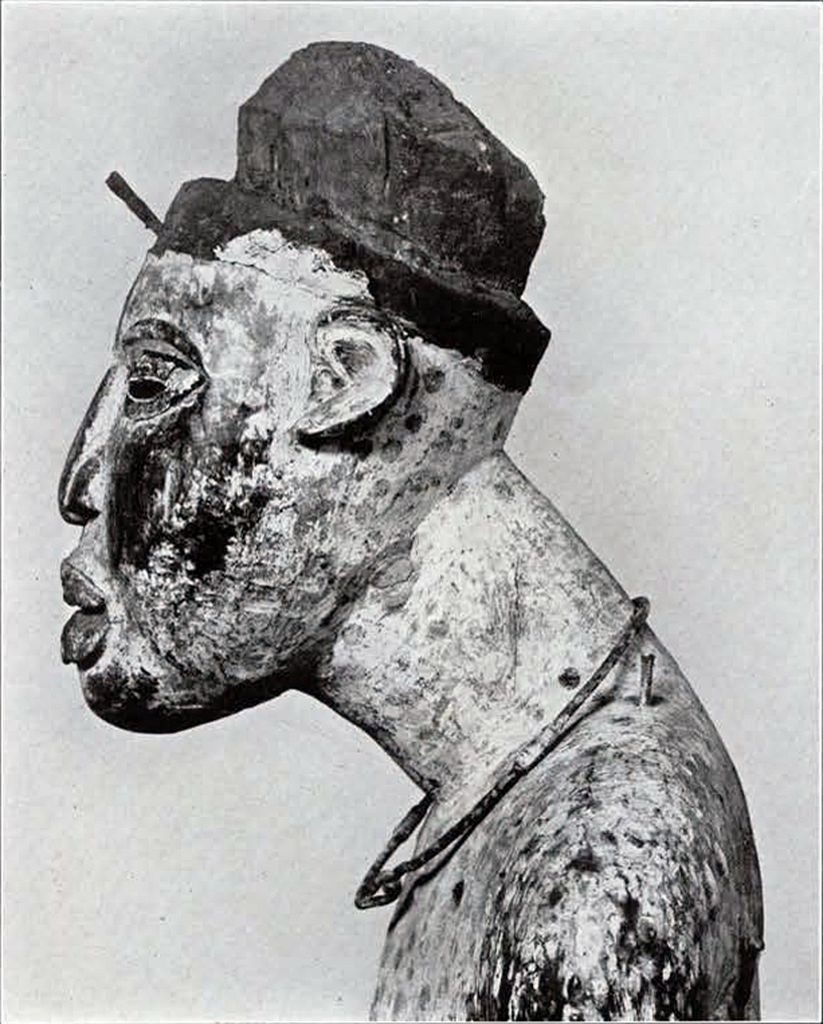

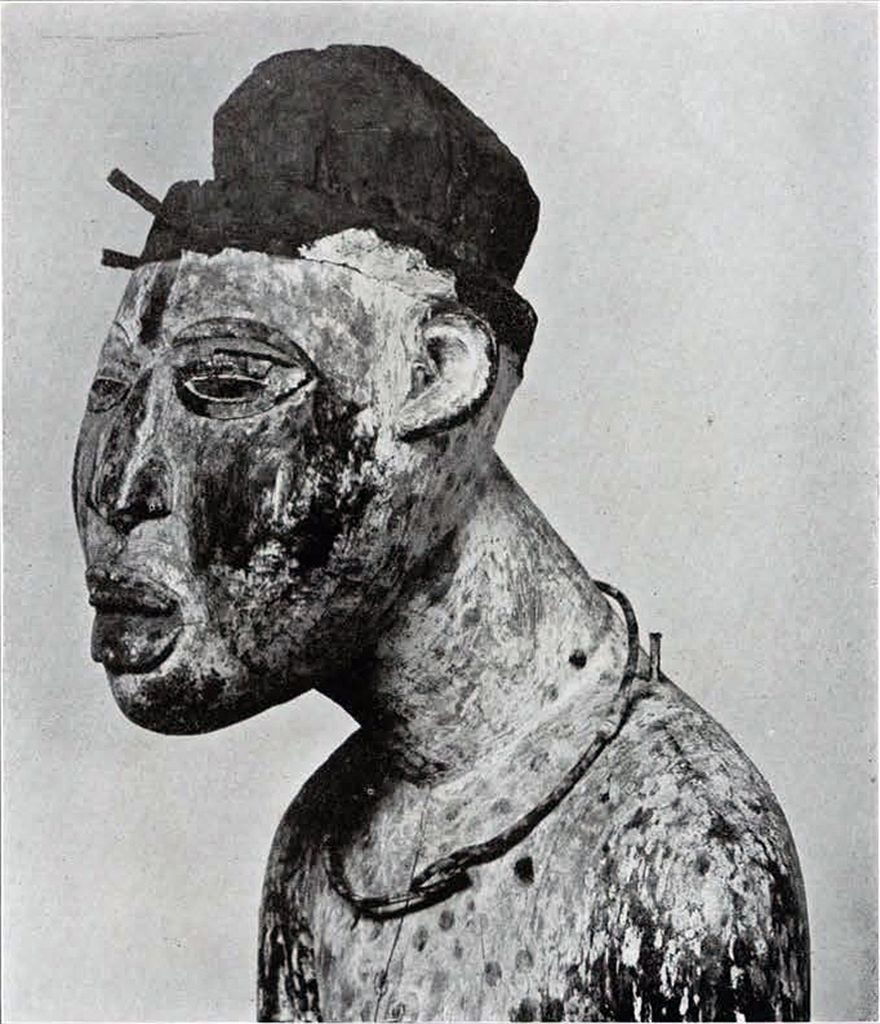

The “nail-fetish” shown in Fig. 12 is a wooden statuette 28 inches high. It is a typical western Congo figure, naively realistic in execution, bringing out by the broadest and simplest means the salient characters of the physique of the Negro of that region. The disproportionately long torso and short legs, the splay feet, columnar neck with the marked forward tilt, as of some primeval near human type not yet fully at home in the upright posture. The caricaturist often produces a better likeness with his faculty for discriminating exaggeration than the photographer. The Congo artist is, so to speak, an unconscious caricaturist without a sense of humor. He gets his effects with no laboring of details. The stumpiness of leg of the forest Negro who is his model is emphasized by the almost complete lack of differentiation between thigh and lower leg and the placing of the bulge of the calf behind the slightly indicated knee. The peculiar balance of the head already referred to, the remarkable flattening of the profile of the face, the most carefully executed part of the figure, all combine to give an excellent idea of the type.

The whole figure has been whitened, though the whitening has been rubbed off in many places. The chest and the back of the neck and of the head bear large blackish dots. There is a rectangular cavity in the abdomen which has carried a mirror or other powerful “medicine.” A nail is stuck in each breast, an arrowhead between. In the middle of the slightly raised panel which represents the shoulder-blades there is a shallow round hole into which another nail has been driven with a bent one beside it. About the neck is a wire necklet, a rope of twisted cloth encircles the ankles. These two articles are probably of the nature of votive offerings. The unfinished appearance of the top of the head is due to the removal of a resinous concretion which formerly represented a cap or coiffure.

This figure was a “nail fetish” of the Bavili people, who inhabit a region where fetishes of this nature are plentiful. When the “virtue” has gone out of these fetishes—note the removal of the coiffure and of the “medicine” from the cavity in the abdomen—they are readily sold to foreigners. The “nail fetishes” of the Bavili are prepared and employed in the following manner:

The nganga, or wizard, who is attached to the service of fetishes, gathers a party of men, whom he leads into the woods to cut down a tree for the purpose of making the figure. On this occasion, if a man should call another by name, the latter will die, and his kulu, or spirit, will pass into the tree and become the kulu of the fetish made from it. The person whose infringement of the name taboo is responsible for this, will answer with his life to the relations of the man whose death he has thus brought about. In any case someone must die in order that a kulu may be secured for the fetish. A boy known for his high-spiritedness, or a hunter celebrated for his daring, is selected and the party goes into the bush and calls his name aloud.

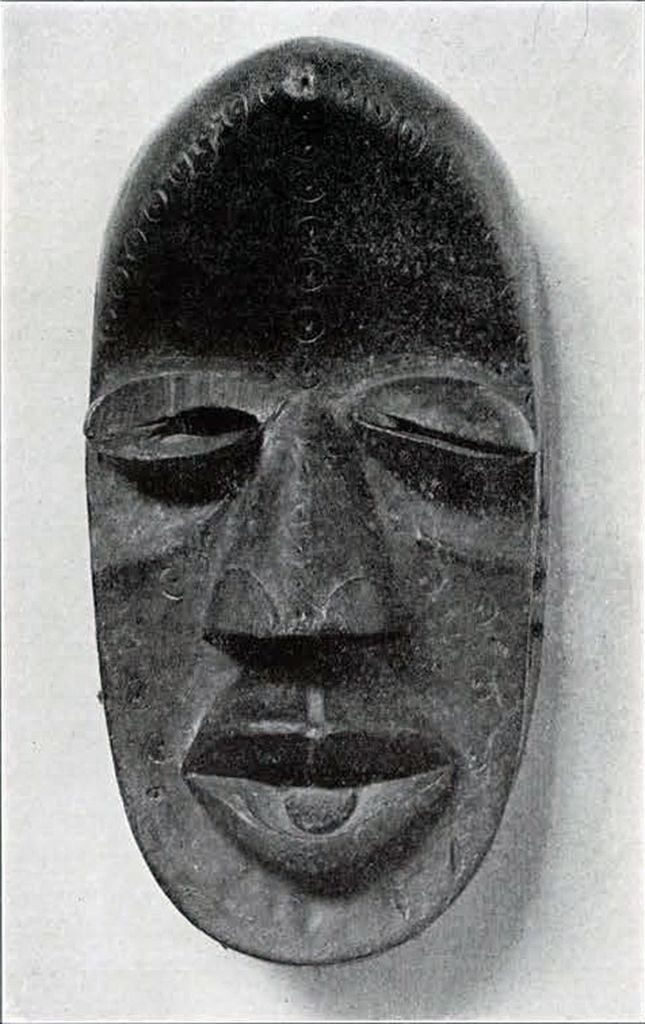

The mask here shown is typical of the masks used in some unknown ceremony by one of the West African tribes. It is of hard wood which has turned black and taken on a high polish from age and use. Its features, faithful to tradition, follow prescribed and conventional lines. The oval contour, symmetrical outline, projecting forehead, massive nose and protruding eyes which slant downward to the outer corners, are characters which mark off this group of masks as the product of one locality, for use in some custom or ceremony.

Image Number: 770

Image Number: 953

The wizard cuts down the tree and blood pours from it. With this is mingled the blood from a fowl then slain. Within ten days the man whose name was pronounced in the bush dies.

“People pass before these fetishes calling on them to kill them if they do, or have done, such and such a thing. Others go to them and insist upon their killing so and so, who has done or is about to do them some fearful injury. And as they swear or make their demand, a nail is driven into the fetish, and the palaver is settled so far as they are concerned. The kulu of the man whose life was sacrificed upon the cutting of the tree sees to the rest.” We have here a combination, with certain modifications, of all three ideas stated above to be involved in the cult of the nail fetish.

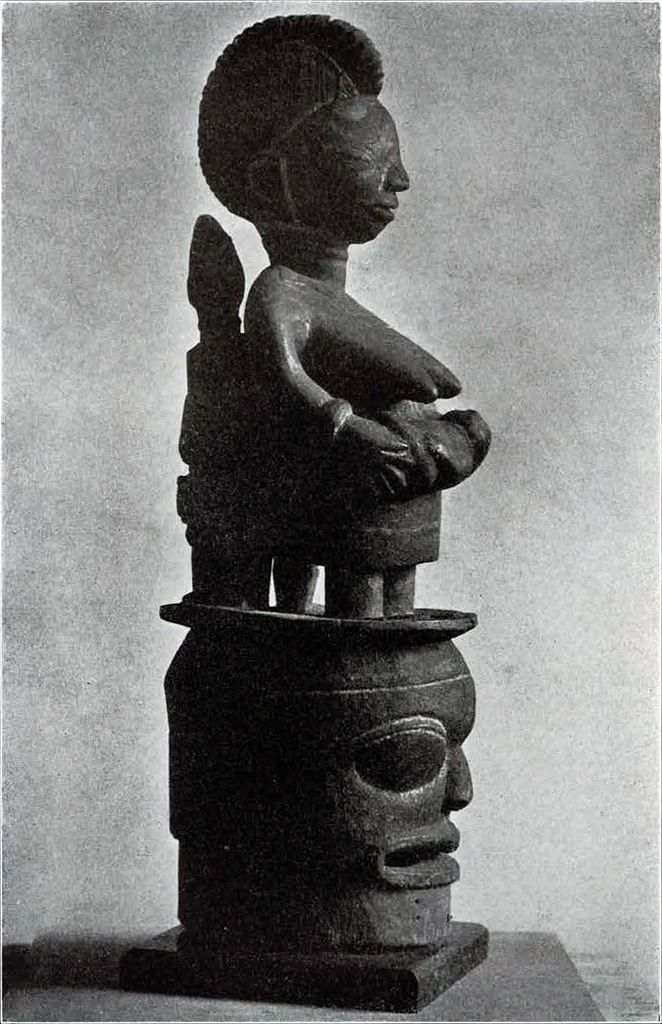

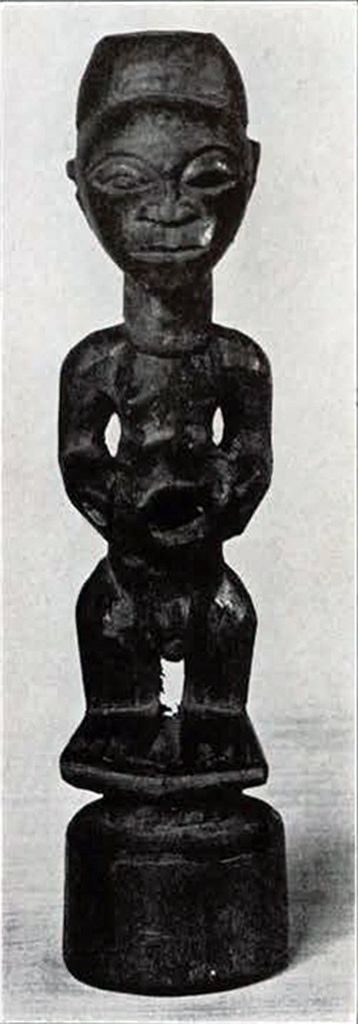

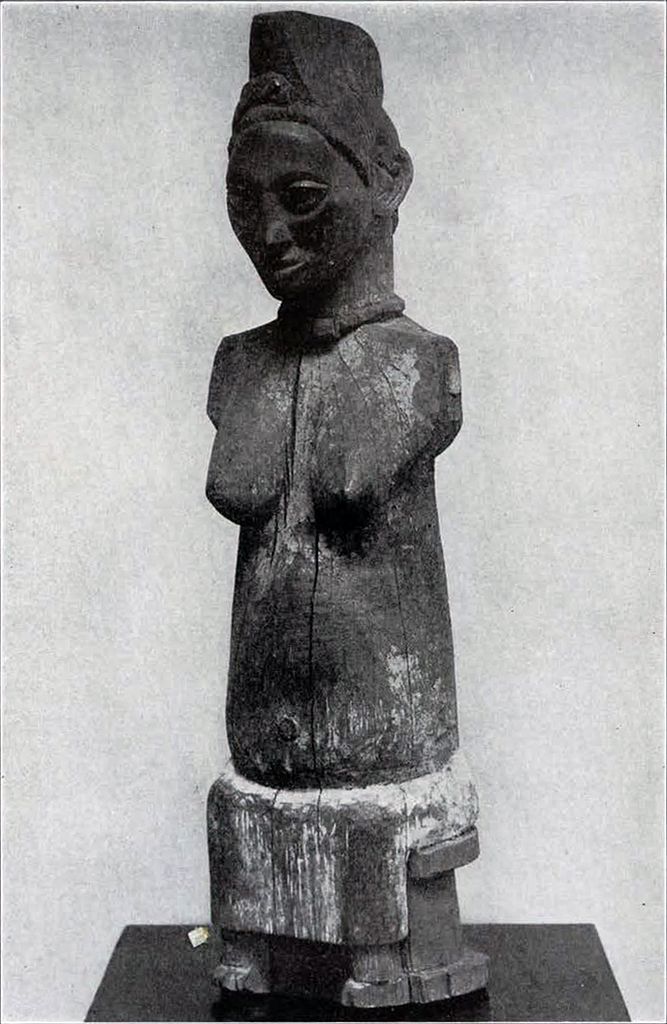

The other large figure reproduced here (Fig. 11) is of uncertain provenience. It is certainly a product of the Congo region, probably from the interior, from some group of the superior Baluba-Bakuba stock. The art of these people is the most remarkable to be found in Negro Africa. The portrait statues in wood of the earlier Bakuba (Bushongo) kings, show an individuality as well as a degree of skill in execution unequaled in Negro art. The head of Fig. 11 is, as usual in African, even in Bakuba, art, the feature to which most attention is paid, and here a result almost of delicacy of feature and expression has been arrived at. The figure is of hard brown wood. The arms are carved in relief on the sides and front of the trunk. They are bent at the elbow and the forearms, carried up in front of the body, join at their extremities, where the hands should be, under the chin in an attitude of prayer or entreaty. The legs, disproportionately short and stout in comparison with the long, slim trunk, are bent at the knee, as if giving way under the weight of the body. It is evident that the position of the limbs is intended to give to the figure an expression of beseeching terror. This is hardly reflected in the face, however, in which the only mark of any unusual feeling is in the slightly parted lips. These are prominent, but not unduly thick. The bridge of the nose is fairly high, and the whole feature would not appear markedly negroid if it were not for the abrupt flattening of the tip, as if the artist had sliced off an originally more rounded surface to get an effect corresponding to a corrected impression. The broad cheeks and the central bulge of the forehead above the sunken eyes put in with bits of glass, combine two typical with a distinctly untypical (the last) character. There can be little doubt that this figure is a study of an individual—perhaps of a slave girl or other victim of a war party, maimed, and awaiting, numbed with terror, the coup de grace the joined stumps of her arms appear to deprecate.

This mask, made in a different part of the country, differs markedly from the one shown in the last figure. In this instance the chin is pointed, the nose small, the eyes set in broad and elongated depressions which are painted white. The mouth also contrasts by its smallness with that in the other illustration. The surface of the mask is intersected by lines which represent the scarification practiced by many African tribes upon their persons. It is supposed that this mask, as well as those shown in Figs. 20 and 22, are constructed strictly on traditional lines for definite use in some tribal ceremony.

The conical coiffure is built up of a substance similar to that of which traces appear on the head and abdomen of Fig. 12. The claw embedded in the apex of the coiffure indicates the fetish nature of the figure. The white markings on the cheeks, along the jaws, and the remains of similar markings on the forehead are probably tribal marks. There are indications that parts of the figure—the loins, the cleft along the backbone, the neck—have been stained red with powdered camwood, which, like the resinous concretion on the head, is considered throughout the Congo to have magical properties.

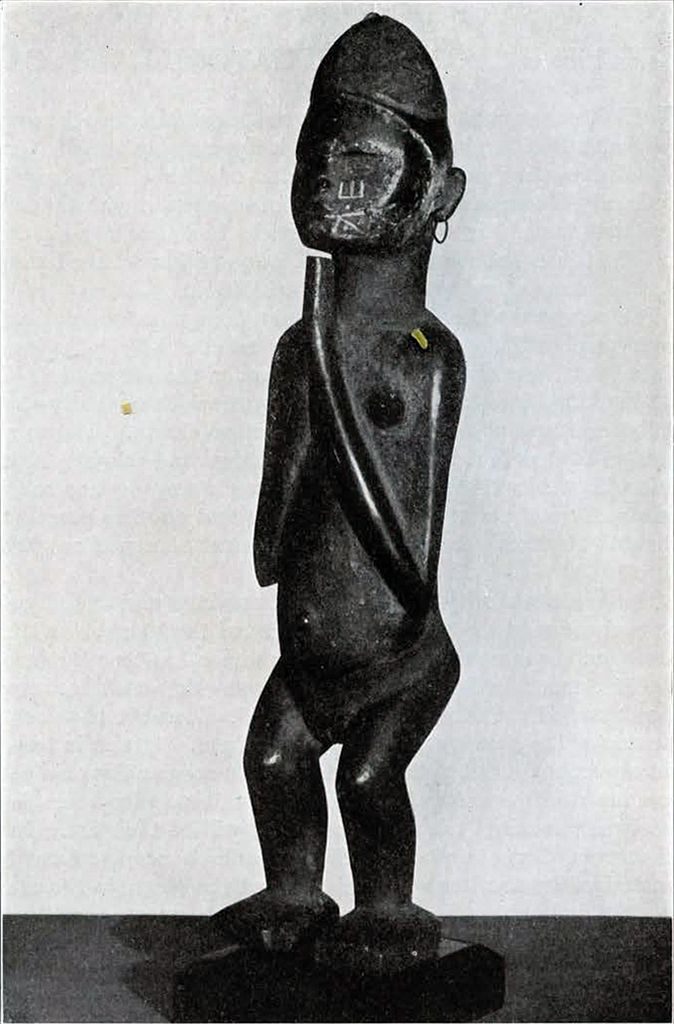

Figs. 13-16 represent a group of fetishes from the southern Congo region between the Kasai-Lulua river to beyond the Sankuru. This region is dominated by the Bakuba-Baluba group of peoples, immigrants many generations ago from the north, probably from the Chad drainage basin, by way of the Shari and Ubangi rivers. They founded strong kingdoms south of the main stream of the Congo, the powerful Lunda empire was built up by people of the same stock, and their art is the most individual and interesting in Africa. This is especially the case as regards the Bakuba, the “people of the thunderbolt,” who call themselves by the name of the weapon which won them their supremacy, Bushongo, the “people of the throwing-knife, ” though that terrible missile is no longer in use among them. The art of the whole region shows unmistakable Bakuba influence.

In Fig. 13, a Bakuba fetish, the receptacles for “power” are round holes in the abdomen and the top of the head. This is the case also with Fig. 14, a smaller figure from the Basanga, a Baluba tribe. The “medicine” is apparently still in the holes. It has also another source of “influence” in the snake- or lizard-like skin girdle.

Museum Object Number: AF1339

Image Number: 701

Fig. 15 is from the Bena Lulua, also a Baluba group. The groovings of the face and body represent the scarifications with which the people of the region ornament the skin of their faces and bodies. The markings on the neck and temples are tribal marks. The Bena Lulua are said to be the only African tribe who practice a form of “cut-out” scarification similar to the scar tattooing of the Maori of New Zealand. The lower portion of the left arm of this figure has been broken off. It held a cup, which was the receptacle for “medicine.”

Museum Object Number: AF4697

Image Number: 741

Image Number: 810

The mask here shown is of another type which has little resemblance to either of the preceding. It is oblong in shape and rectangular in outline. The entire flatness of the features is relieved only by the small projecting nose. The mouth is represented by a flat elevation marked by a slight transverse incision. The eyes are simply holes, colored black. The coiffure, is indicated by a series of crisp wavy incisions and by the black paint with which that part of the wood is covered. The entire face is painted white.

This profile of the head and shoulders of the nail fetish shown in Fig. 12 brings out some of the marked characteristics of that image. Here one sees the massive face, the undeveloped chin, the flat nose, everted lips and small skull, physical characters which appear in varying degree in a certain type of Negro. The illustration shows the forward projecting neck which seems to be weighed down by the heavy face and recalls the attitude of one of the anthropoid apes or of the primitive human being emerging from the brute. The crown of the head was formerly fitted with some kind of coiffure. The nails driven into the head, shoulders and trunk correspond to petitions. The entire body is painted white.

In this illustration the character and expression of the face of the image shown I in Fig. 12 are brought out more clearly. Reference to that figure will show the heavy trunk, long arms and short legs which combine with the head and face to convey the idea of brutal strength. The entire work portrays with force and emphasis certain characteristics that belong peculiarly to some of the West Coast Negroes.

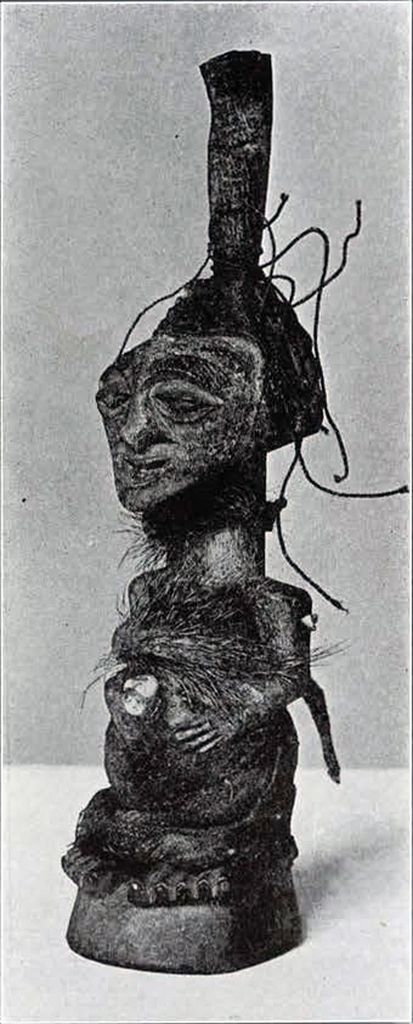

This figure may serve to illustrate the characteristic ways of introducing “Medicine” or special virtue or power into the image. The medicine consists in this instance of a human tooth in the abdomen, a smaller one on the receding forehead and another in the left shoulder. Power also resides in the point of an antelope horn inserted in the crown of the head and filled with some magic substance. The hairy skin of some animal about the body and neck also contributes its measure of virtue. The rag wrapped around the lower part of the body represents the kilt of a chieftain. The modeling of the figure is worthy of study. The head and face especially show both skill and imagination. The treatment of the eyebrows and the hair is a clever bit of technique that, together with the spirited freedom of the features, gives character and expression to this interesting figure.

Fig. 16, also a Baluba figurine somewhat larger than the three just referred to, has less individual expression than the others, and in the execution of the rest of the figure conventionalization has gone to much greater lengths. The arms are mere loops, the hands, in the customary position, pressed against the sides of the abdomen, are indicated simply by a flattening of the ends of the arms. The hips and legs form a single block, the upper part of a pedestal for the trunk; the feet, also undivided, with the toes forming a continuous row, serve as the base of the pedestal. Whatever—probably glass or shells—was used as inlay for the eyes has disappeared. There is a deep hole in the top of the head in which is inserted the thin end of a small corncob.

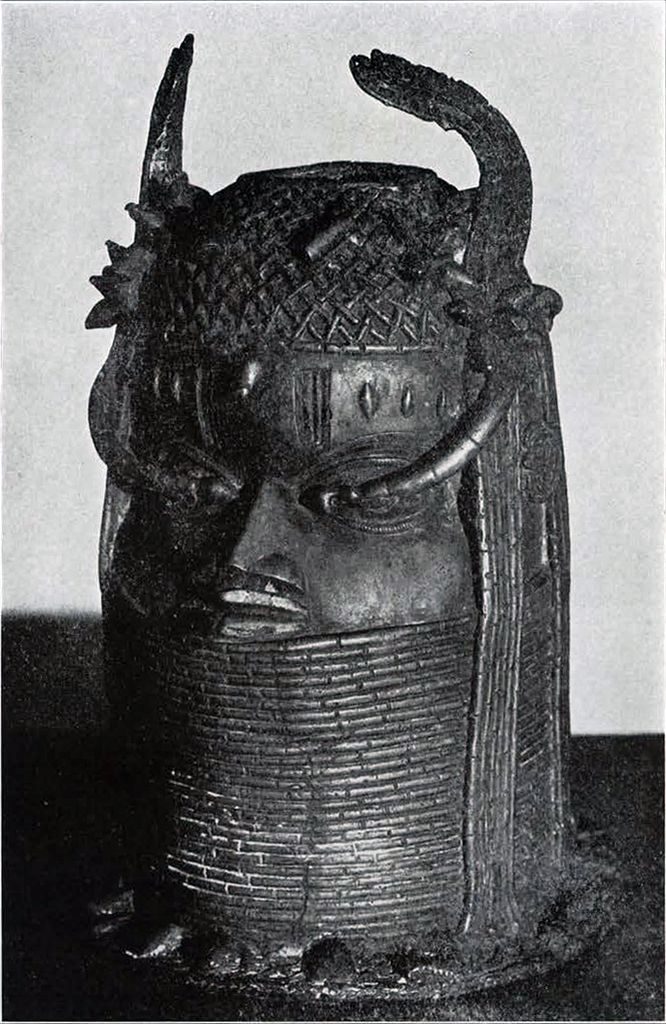

With the next example we pass to a region much further west—the Cataract region of the Congo below Stanley Pool (Fig. 17). The peculiar crested coiffure; the curved and angular outline of the hair sharply defined against the smooth surfaces of the forehead and back of the head and the striations of the temples, cheeks, and jaws; the clean cut trapezoidal beard; the steeply protuberant crescent of the mouth; the barrel shaped trunk from which the thick neck with its peculiar bulge about the middle rises abruptly; the short calfless legs of which the thigh is merely suggested by the beveling off of their junction with the body; the hoof shaped feet; the bare indication of the bent arms cut in low relief against the sides of the trunk and merging into the abdomen just below the rectangular depression intended to receive the “medicine;” the blackening by fire of the surfaces intended to represent the hair of the head and beard; all represent the type of a large group of figures peculiar to the Lower Congo in which conventionalization has proceeded so far as to preclude any opportunity for a display of originality on the part of the craftsman, except by such obvious means as slight changes in the relative size or the shape of some features or of the spaces separating them.

Museum Object Number: 22221

Image Number: 696

Fig. 18 is another specimen whose provenience is not determined. The cord wrapping which binds strips of palm fronds to the body suggests the Congo coast region. The almost complete absence of forehead, the short blunt nose, wide mouth with everted lips, the immense ears, and the marked prognathism, are all indicated with a simplicity of method and a directness all the more notable for the very small scale of the figure; the result being a remarkable representation of a peculiarly brutal Negro type. The upper eyelids bulge forward under the heavy brow ridges, but there is no attempt to indicate the eyes—or else these are lost under the encrustation of dirt, or possibly of some form of pigment with which the head is partially covered. Here the virtue of the fetish, if it is one, probably lies in the leaves under the wrapping of cord about the body. The figure stands on a pedestal which is trimmed to a point at the lower end and inserted in a pointed iron ferrule. A similar device for holding fetishes in the hand during certain ceremonies, or keeping them upright by sticking the point into the ground, is found not only in the Congo but also in the Benue-Niger region. The figure bears a rather close resemblance to the small stone figures of Yorubaland.

Museum Object Number: AF1346

Image Number: 758

Museum Object Number: AF1346

Image Number: 757

In Fig. 19 we have a representation of a dog, of native African type, with the jaws open showing the teeth, or those few of them which the craftsman who made it had sufficient patience to carve out. The eyes are put in with small pieces of white glazed earthenware (European). On the back there is a circle of resin which formerly held the “medicine.” The tail forms a ring which may have served to suspend the fetish. Another ring of stout twisted wire hangs on the ring of the tail—possibly an offering. The figure is from the coast region near the mouth of the Congo. The legs have been broken off short; the under part of the body is coated with the magical red camwood powder.

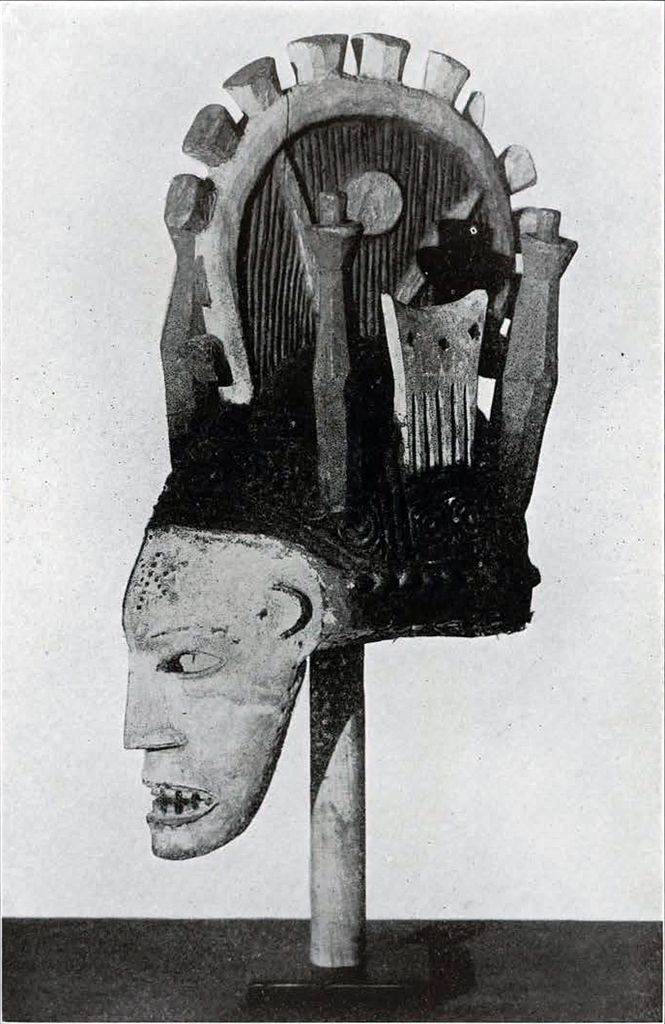

The wearing of masks is connected with funeral and memorial ceremonies, with the initiation of youths into the full social life of the community or into secret societies, with the activities of the secret societies themselves, and with the fetishist practices of medicine men. In most cases they form part of a dancing costume. The mask, Fig. 20, probably from the Ivory Coast, with its sharply protuberant features, bears a close resemblance to the mask worn by members of the Babende secret society among the Bakuba. This society was founded by a great chief of the Bakuba to facilitate the capture of malefactors. Very often these secret societies exist chiefly as a means of securing the dominance of a particular caste. In West Africa there are powerful secret societies among the women. But usually the masked figures which are supposed to be the embodiment of spirits of the dead or of other powerful spirits are an object of terror to women and children, and to the uninitiated generally, and thus help to maintain the supremacy of the members of the ruling caste. The Babende maskers on certain occasions dance in public; if a woman touches one of the masks, they kill the first goat they encounter, and the offending woman has to pay the costs.

Fig. 21 is a mask of the Bakete, a subtribe of the Bakuba. The prevailing color is brown. A slightly sunken space surrounding the eyes and extending to the ears is painted white. The narrow slit between the eyelids is not cut through; a crescent shaped hole has been made below the eyes for the wearer of the mask to look through. The forehead juts forward in a sort of peak extending to the front ; not so markedly, however, as in the last example. The narrowing of the protuberance of the mouth towards the front gives it the appearance of a proboscis. The triangular incisions of the brown colored part of the face probably represent scarification. Both these masks are pierced at the edges for the attachment of a fringe of grass or fiber.

Extreme simplicity of plan marks the last example shown (Fig. 22). The long oval of the face is whitened except at the chin, which, like the other darker portions of the border, is browned by the action of fire. The very small eyes, the snoutlike appearance of the nose, the extreme length of the upper lip, and the narrow slit of the mouth at the top of the moundlike formation of the lower part of the face, all suggest that this mask of the Fan people on the Ogowe river of the west is intended to represent the head of a baboon.

Fig. 32, a Basonge (Baluba) fetish, with its skin wrappings, the human tooth set in the middle of the abdomen, and the rag of trade cloth wrapped around the hips in imitation of a chief’s kilt, illustrates well the application of extraneous “medicine” to the fetish figure to endow it with power.

In Fig. 33 we have what appears to be a fetish rattle from the Nkimba tribe near the Stanley Falls of the Congo. Two seated figures each support a carrying yoke on its shoulders. This may be compared with Fig. 18 for the handle, used either to hold the object by or for the purpose of setting it upright in the ground. The rattle is formed of a number of nut shells fastened at the top of the handle and below the block on which the figures are seated.

H.U.H.

Museum Object Number: AF2062

Image Number: 614

Museum Object Number: AF5122

Image Number: 976

Museum Object Number: AF2002

Image Number: 719

Image Number: 744