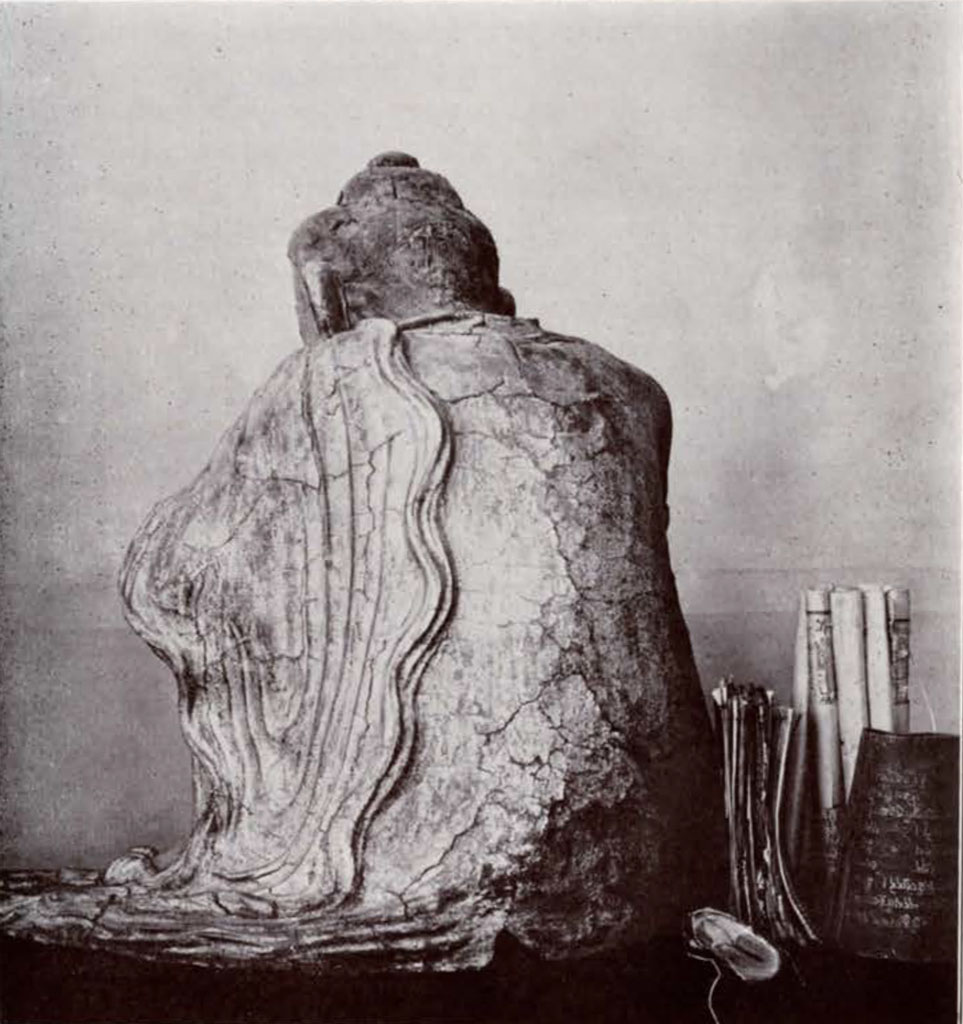

ONE of the most striking objects in the Chinese collections of the Museum is the strange statue of a Buddha, or a disciple of Buddha, executed in what is known as “dry lacquer.” The material of which it is made is unusual enough in itself to arouse interest, but the pose and expression of this seated figure also are so unique and extraordinary that it attracts considerable attention.

Museum Object Number: C405A

Image Number: 1425

The Buddha, or Disciple, is seated with the left knee drawn up opposite the chest and the other leg bent horizontally before him with the sole of the foot lying upwards. The hands are placed one over the other upon the raised knee and the chin rests on the hands in an attitude of deep meditation. Such amazing use of strong opposition in the line composition is startling enough, the line of the raised leg being practically at right angles with those of the arms and the other leg; but the head is undeniably the focus of interest, both because of its being at the apex of the pyramidally composed figure and because of the mysterious smile of amused self-satisfaction that plays over the features. In spite of the attitude this is no being of deep spirituality lost in profound thought and oblivious to the world around him. Although his eyes are nearly closed he is perfectly conscious of being the center of attention and is pleased to be considered an enigma. The curve of the heavy eyelids is as expressive of amusement as is the curve of the lips. The large broad head with its long narrow loop-lobed ears is thrust well forward in order to rest the chin upon the hands and this gives the rounded shoulders just the suggestion of a shrug. Altogether it is an unforgettable figure; not for grace and beauty, for it has little of either, but for the daring strength of its composition and the mysterious power of its expression.

The figure is clad in a heavy mantle which leaves the right arm and chest bare and falls in thick unwieldy folds which spread out over the flat base upon which the statue rests. The whole of the figure is gilded except for the hair, which is represented as black. It is parted in the middle and drawn back on each side in a thick smooth curving wad to the top of the ear. On the cranium rises the ushnisha in the form of a large low hump with a small round lump perched on top of it, while another lump, not so small, appears in front of it. This front hump is not black like the rest to show that the hair grows up over it but is gilded as if to represent some ornament or perhaps the bare skull. A wide shallow round hole in the forehead is the urna, another of the marks of wisdom and holiness of the Buddha. It doubtless originally held a jewel or crystal.

The statue is life size, measuring three feet eight inches in height, and was acquired by the Museum in 1923. It is exceedingly important as an example of Chinese dry lacquer sculpture, for although many Japanese figures in this technique are known few Chinese ones, even of the later periods, have come to light.

It is known from literary sources that the technique of dry lacquer was developed in China long before it was introduced into Japan. The researches of Prof. Pelliot have revealed historical records showing that dry lacquer statues were made in the fourth century A. D. by a sculptor named Tai K’uei who worked for the Court, in and near Nanking. He died in 395 A.D. According to Mr. Ashton, Tai K’uei made five processional images for the Chao-yin ssŭ temple and these were later removed to Nanking, where they were kept in the Wa Kuan ssŭ temple with the famous jade Buddha, sent by the King of Ceylon in 404 A.D. to the Southern Court, and Ku K’ai-chih’s painting of Vimalakirti. Records of the Wei, T’ang, and Sung periods also mention statues in this technique, which was termed chia ch’u, or, in the later records, t’uan huan. It would seem that dry lacquer was much in favor in the early T’ang period, during which time it was introduced into Japan. There, by the middle of the eighth century, it had become exceedingly popular and had developed into a very high art. Indeed, Kanshitsu, as the Japanese called this process, lent itself better than wood or stone to the rendering of pictorial effects through the softness of contours and the flowing grace of draperies. Some of the finest Japanese sculptures known are in this medium. After about one hundred years, however, lacquered wooden figures came into fashion in Japan and Kanshitsu was neglected and finally forgotten. In China the technique suffered eclipse about the same time, that is during the ninth century, but there was a revival of it in the Yuan Period (1280-1368 A.D.). Here again the records mention some names. At the court of Kublai Khan was a Nepalese youth, already famous at seventeen, named A-ni-ko, who made religious images and had many pupils, one of whom, Liu Yuan, became well known as a sculptor in dry lacquer and “made many statues for the temples in Shang-tu and Peking.”

In spite of the fact that dry lacquer sculpture was so popular for a time in China that there must have been a great deal of it, and although it was of very durable material, there seem to be few actual examples now known. Japanese temples contain many fine Japanese works in Kanshitsu but most of the Chinese figures appear to have perished, probably through the frequent fires which destroyed the temples themselves; and what we know of this class of sculpture has so far had to be gleaned mainly from literary sources and from a study of the related Japanese examples. There are a few Chinese works known to be in existence, however. None of them is dated. Professor Siren lists four which he says are the only ones, so far as he knows, “which on stylistic grounds may be ascribed to the T’ang period.” They are said to have come from Chihli province, from a temple called Ta Fo Ssŭ near Paoting Fu. One is now in the Metropolitan Museum; another is in the Walters Collection, Baltimore; a third, of which only the head and shoulders remain, belongs to Yamanaka, New York; and the present whereabouts of the fourth is not mentioned. These examples are of Buddhas seated cross-legged in conventional attitude. They are simple, almost severe in modelling, of great restraint and dignity of pose and aloofness of expression. The softness of surface contour and the crisp but sensuously graceful lines of the drapery place these figures by the side of the lovely Japanese examples of the eighth century. A fifth statue which is considered by some to be a Chinese work of the T’ang period is the seated portrait figure called Yuima-Koji (Vimalakirti), which has been one of the treasures of the Hokkeji nunnery, near Nara, for many years. Records of Todaiji, the companion monastery, seem to indicate that this dry lacquer figure was presented in 747 A.D. by the Empress Komyo Kogo. The style bears out this date. Several other Kanshitsu statues in Japan may be practically Chinese, such as the beautiful Rotchana Buddha of Toshodaiji, Nara, which tradition ascribes to a Chinese monk who came to Japan in 754 with the master Kuan-shin, bringing some of the latest developments in the process. Thus this Buddha is supposed to have been made over a core of woven basket work. I do not know if it has been examined to determine whether this be true. In the Ostasiatische Museum, Cōln, is a statue in dry lacquer of Myroku Bosatsu thought to have come from Korea and to be very early.

Museum Object Numbers: C405A-C405H

Several later Chinese statues in dry lacquer have recently become known. Dr. Siren mentions three which he ascribes to the Yuan period, the time of the revival of the technique; one of a standing Bodhisattva which was exhibited at the Cernuschi Exhibition of 1924, a second of the same group but seated, and a third, also seated, which was in the possession of Yamanaka, New York, and has now passed into a private collection. A fourth example is this Buddha in the University Museum.

We have referred to the dry lacquer process as if it were a technique well known. Actually it is rather obscure, although the main points are clear enough. In the T’ang and pre-T’ang periods clay statues were very common. The method of dry lacquer grew out of an attempt to find a material that could be modelled easily, like clay, but which would be more durable, would not break so readily. At first, apparently, some vegetable fibre was mixed with the clay to strengthen it. The next step was to cover the clay statue with a coat of lacquer or with cloths dipped in lacquer. Then it was found that details could be freely modelled on the surface with a rough paste made of wet lacquer mixed with lint, vegetable fibre, or even sand. Three main variations of the process were evolved. The simplest was that of covering a roughly carved wooden figure with a coating of coarse paint on which was laid a layer of cloth. Several coats of carefully prepared lacquer were then applied and the thick paste described above could be used to mould folds of drapery and other such details and, furthermore, when dry could be carved like so much wood. The figure in the Walters Collection seems to have been made in this way. But such a statue would still be heavy. The more perfectly developed process is suggested by the term which was commonly applied to it, chid ch’u, which means “wooden frame.” A rough skeleton of wooden splints was built up and upon this were hung cloths which had been dipped in lacquer and which were set in place or hung in folds as desired and left to harden in that shape. The head and hands were usually modelled in clay, covered with the lacquered cloth, and when this was stiff and dry the clay was dug out and the hollow pieces fastened to the statue. Joinings were covered with lacquer, modelling of details was done with the lacquer paste, and the whole was gilded when completely dry. It was then but a hollow shell, supported inside by a framework of wooden beams, a statue light in weight and admirably adapted for carrying in processions. Many of the Japanese examples were made after this fashion, notably the great twelve foot high Fukukensaku Kwannon of the Sangetsudo at Todaiji.

The third variation of the process lent itself to the highest development of the art of dry lacquer sculpture. A core of clay was made upon which was laid first a coat of finely prepared lacquer and then several coarser ones. The whole was then covered with cloth, sometimes with two layers of cloth. Then coat after coat of lacquer was given it until the surface was like burnished bronze. When dry the clay core was dug out, leaving the hard light lacquer shell. As in the previous case, head and hands were often made separately and attached to the trunk, the joinings covered by the many successive coats of lacquer. Lacquer, which is the thick greyish sap of the Rhus vernicifera tree with the impurities and water removed, is very slow in drying and as each thin coating must dry thoroughly and be highly polished before the next coat can be put on the name by which this third process became known, t’uan huan, or “slow modelling,” was very appropriate. As M. Hamada remarks, the “whole process was unspeakably laborious and took much care and time.” However, it made most beautiful workmanship possible and the statues were very light and easy to carry, did not break and were not attacked by insects.

The details of the technique cited above have been gathered from Chinese and Japanese literature on the subject. The tradition that a woven basket work foundation was used for the Rotchana Buddha as a variation of the method in the eighth century is an indication that the artists invented new tricks of the trade from time to time and suggests that a careful study of each statue would show many interesting differences. It is unfortunate that so few Chinese examples of dry lacquer sculpture are known.

We have examined the construction of the Buddha in the University Museum and will describe it in some detail. Several features of its technique are novel.

First there is a flat wooden base which was made by joining two wide boards together side by side with iron staples and roughly rounding the whole into an uneven disc. In the middle of this is cut a rectangular opening by which access can be gained to the hollow inside of the figure. This hole was closed by a small wooden door hung on a flap of cloth.

From this base a wooden post goes up through the middle of the figure, running up the left thigh to the knee and chin. One can see the ends of other wooden splints which seem to support the shoulders. One such end is wound with cord of the nature of raffia.

Around this framework there appears to have been built up a crude core of white clay. Later, after the statue was completed, this core was removed but there was left, as telltale evidence, a thin coating of the clay over the interior, like a “slip” on pottery.

Upon this rough clay core was moulded layer after layer of paper; a tough paper, probably put on wet almost to a pulp, although it maintained its separate layers and therefore could not properly be termed “papier maché.” Some of this paper had writing on it; characters an inch high show in one place.

A coating of coarse lacquer seems to have been put on next, and on this a layer of very rough cloth, like burlap, was fitted smoothly. Over the burlap was the thick layer of coarse lacquer paste modelled to a height of perhaps an inch in some places. The thick folds of the drapery are built up out of this paste. It is extremely hard and tough, has somewhat the appearance of a fine cork in texture and color, and has cracked badly with age. The very highly polished surface—where it remains—shows a fine thin coating of red lacquer as a finish. The gilding already described is now quite worn off in places.

It is impossible to tell whether or not any clay still remains in the head and hands. The hands were probably not made separately in this case but I believe that the head was. The way in which it is set on to the body gives that impression, and it shows more care in modelling and in details than the rest of the figure. Inside, the hollows of shoulders and arms are stuffed with masses of a coarse sawdust soaked in lacquer (probably), and with some of the lacquer paste. The whole interior, hard paper with the thin clay slip, has been stained a dark red-brown.

Museum Object Number: C405C

Image Number: 1426

There is some evidence that two layers of cloth were used. Where the toes of the left foot have been damaged the cloth has been laid bare and two distinct layers may be seen, here separated only by a thin coating of a greyish powder, perhaps the preparation Prof. Hamada says was put between the cloth in some cases, a mixture composed of powdered whetstone and powdered earthenware. Whether there are two layers of cloth over the whole figure cannot be determined; only one appears at a damaged spot on the left shin.

A rather perplexing question is that of the identity of this figure. As has been noted the pose is a very unusual one. Only two other examples of it have come to my notice, both of which are in the Royal Ontario Museum at Toronto. The one is a small marble figure of a hairy, wrinkled, unkempt looking sage with curly beard and mustache and a large flat ushnisha, which, as in the case of the lacquer figure, has a hump in front of it not covered with hair. The attitude is almost certainly that of samādhi, an ultimate state of meditation in which perfect rapture or ecstacy is reached. Cūda-panthaka, one of the sixteen Lohans, seems to be represented in this attitude sometimes according to De Visser, but I have found no sure representations of him in exactly this pose. The other example in Toronto is a statuette in glazed pottery of a gnome-like figure with huge nose, pointed beard, and hair drawn up to a high top knot. The chin does not actually rest upon the hands however. It is not in the least Buddha-like. The dry lacquer figure in the University Museum, on the other hand, has the appearance of a Buddha, with its sleek smooth shaven face and the prominence given to the three chief “marks,” the urna, the well defined ushnisha and the long ears. M. Salmony suggests that the pose and figure are that of Gautama Buddha in his final meditation just before he obtained Enlightenment.

It might be hoped that among the papers found in the statue would be something to indicate the identity of the figure, but apparently these books are merely portions of sutras, or Buddhist scriptures. Five, or parts of five, different works were concealed within the hollow Buddha, together, so we were informed, with bags “perfumed ashes to protect the lacquer from worms” (probably the wooden framework) and a small parcel “containing the five organs made in silver but very rudimentary.” The perfumed ashes and silver organs have disappeared but the papers are still with the figure. They comprise:

- Three pages of a Tibetan Creed Book written in white and silver Tibetan characters on deep blue paper of a very heavy quality. There are two holes for the pins which held the leaves of the book to its carved wooden covers. The title of the work to which these belonged has not been determined.

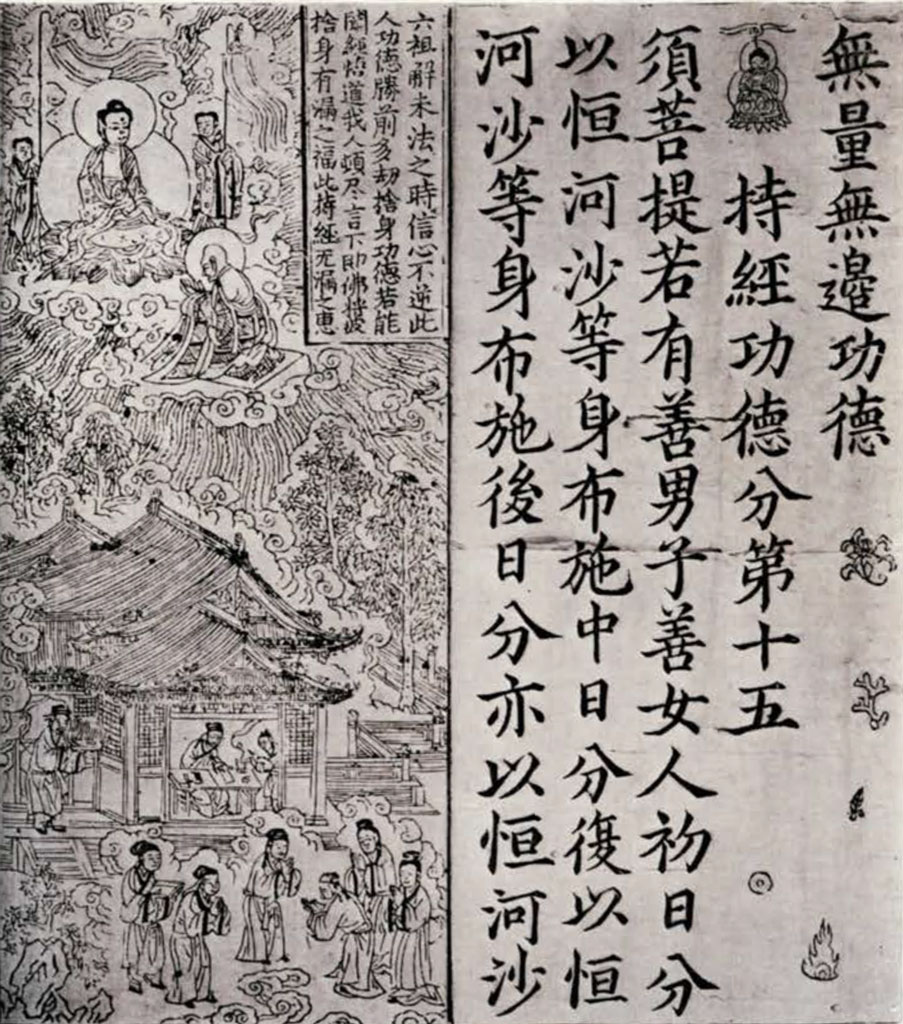

- Two long sections torn from a large sûtra printed in Chinese and illustrated with many wood block cuts. The reproduction on page 293 shows two pages of this paper but does not show the margin above or below. This, and the books following, were of the “accordion” type; that is, made of one long strip of paper folded back and forth upon itself between the two covers, the portion between two folds comprising a page. The printing in this case is of very good quality, the characters are well shaped and nicely arranged, and the woodcuts show good craftsmanship. The paper is an old tan of soft but tough texture and is in a strip thirteen inches wide. The folds come at intervals of five inches.The book to which this belongs is probably one of the more popular sutras. The illustration shows the beginning of a chapter on Virtuous Works and bears the title, “No Measure nor Limit to Virtuous Works.” According to the label the woodcut represents a man who, through his good deeds, was enabled to leave his body and come up to Buddha where, in the full realization of the truth of the sūtras, he attained to a state of perfect joy.

- A book of which only the first part was in the lacquer figure. It has a blue paper cover and measures 9½ X 3½ inches. The title on the outside is Chin Kang Kuan Yin Mi T o San Ching, or “The Three Sutras, Diamond, Kuan Yin, and Amida.” It is probably a book of selections from these sutras. One of the first titles found inside the cover is Pan-jo Po-lo-mi-to Hsin Ching, which is the Chinese name for the Prajñā pāramitā hrdaya sutra, commonly known as the “Heart Sutra” of the Prajñā pāramitā. Some distance further on in the book one comes to a second title, Chin-kang Pan-jo Po-lo-mi Ching, the Chinese name for the Vajra-cchedikā Prajñā pāramitā sūtra, corn, monly known as the “Diamond Sutra” in the Prajñā pāramitā. The Sanskrit Prajñā Pāramitā Sūtra is rendered in English (by Giles) as “the sutra of the intelligence which reaches the other shore—Nirvana.’

- Part of a third Chinese Buddhist book probably also made up of selections from translations from the Sanskrit. It has a blue linen cover of the same size as No. 3 and bears the title K’ung-ch’iao Shui ch’an Chin-kang Mi-to Kuan Yin Ching. The text is printed on both sides of the paper.

- A little book in pinkish brown cover which is a copy of the Ta Fang Kuang Yuan Chiao Hsiu-to-lo Liao-i Ching or “Sutra of the full Signification of the great detailed Sutra of the Perfect Perception.” This work was translated from the Sanskrit by Buddha-trāta in the seventh century A.D. This particular copy is doubtless of a very recent edition.

The finding of these papers, portions of Buddhist sutras, in the hollow interior of the statue does not necessarily add to our information concerning either the date or the identity of the figure. The small trap door in the base could be opened at any time and things put in or taken out. There is no paper referring to the statue or what it represents. But in style and treatment the figure is of the later period—not the early Tang. It has not the qualities seen in Tang work, as already described, melting contours, rhythm of draperies, serene aloofness and dignity. The strong opposition of the composition, a certain immovable power in it, point, as M. Salmony says, to a great prototype, but it is a clumsy, lumpy figure on the whole, the draperies fall in folds that are actually ugly and the amused self-consciousness of the face belongs to the art of a later period. It was probably made during the revival of the dry lacquer technique in the Yuan period or in early Ming.