MARRIAGE was honorable in all, and it was about this association of man and woman that all the Tlingit life revolved. Among the better class the formal wedding ceremony was effected by vows; a promise may not have been heard spoken, in their hearts man and wife consecrated themselves to devotion. Thus, before the invasion of foreign influence, a union could not very well be terminated at the will of the husband or the wife, and at that time a man’s word was sufficient means by which a union was bound. But now the white man’s law has created in the minds of both parties a sense of independence—each may do as he pleases, and as the people acquire more knowledge of liberty the once con-firmed custom of choosing a peer becomes vague.

Image Number: 15011

There was a time too when it was a natural thing for one to know who was to be one’s spouse, because the relationship of certain families was ascertained by a genealogical plan. A maid and a youth whose parents were of the same social standing were matched from infancy, and when they grew to a marriageable age no other person interfered. There was always a law which prohibited marriage between members of the same moiety of the two divisions of the tribe. A Tlhigh-naedi man could marry only a Shungoo-kaedi woman, and in such a reciprocal system the parties never failed in observing the ancient rule of choosing a peer.

Generally early marriage was encouraged; there were only a very few unmarried women among the people and the few single lives were caused by either a deficient mind or a belief in being a virgin; in the latter case the woman died unmarried. It was considered a man’s duty to care for and protect the woman, therefore he had no excuse for leading the selfish life of a celibate. Wise men agreed with the old saying that life without a mate is something like an old-fashioned lullaby : at a certain age one grows weary of it ; it becomes monotonous. Even a staunch-hearted celibate admitted that a fair mate makes the world a better place to live in. But one must be cautious in choosing a life-mate, since the motive of sundering an important relationship had been too often love for a woman.

All women were honored for their chastity and industry. The estimation of a good woman generally had lain in her capacity of increasing the clan to which she belonged. But there were families that considered a proper marriage also a means for the creation of a desired friendship and the maintaining of peace. Thus in our women was vested our moral standard, as well as the purity of our blood. The true Tlingit mothers taught their daughters that permanent success in marriage depended much on the wife’s devotion and faithfulness, and that most failures had been caused by woman’s frailty. Once I listened to an aged woman talking to her granddaughter:

“When I was a little girl I was never allowed to leave the house alone; even up to the day of my marriage I dared not talk freely to boys, because I was taught that there are men who are like the beasts of the forest, they are perpetually on a hunt for easy prey, and once that one of these has satisfied his desire, he merely walks off, leaving behind that which cannot be replaced. They are still everywhere, and their burning fire of love burns high, especially at night. Hence, it is not more difficult to find a bad man than it is to find a good one.

“It is true that a fallen woman has been known to rise once more, and proves to be a successful wife. The man in this case may have been only good enough to be kind to such a wife when he displays his generous admiration of her, in the effort to bury her past. But there can be no complete happiness in such a union, because there will lurk always in the man’s heart the secret dissatisfaction with a wife who comes to him from another man. So it is wise to be cautious, and wait for the proper kind of a husband. He is a man to admire, as is a woman who is aloof and reserved, not one who is familiar and accommodating. In our time an honest woman was never an object of show, but now women of coquettish nature are not uncommon. So, my grandchild, not until you have acquired a good life-mate will I aspire relief.”

Image Number: 15017

It was always different with the men. It would seem that the good goddess of Destiny was more liberal in providing for their future. A good man may temporarily deviate, and sink into the mire of life, but he can always rise at will, and shake off all foul matters. Soon his faults are forgotten, and he once more steps out into society, wiser than before. Thus a well trained woman gloried in a male of wide experience. She had learned too that a true man preferred not a woman of easy love, but one whose pride is a promise of resistance.

There is much truth in some reports that marriage among the Tlingit people was primarily by mutual consent of the parents of the candidates; as the young man received a wife from some other prescribed party, and the parents of both parties controlled the connubial contract, personal choice had little to do with the affair. But such prevailed only among the divisions where the custom of peerage had a chance to survive. Indeed, some people are fortunate enough to have everything that makes up complete happiness in life, while others gladly take only that which falls to their lot. In Chilkat there were about as many fair maidens as there were desirable youths, and the parents had no difficulty in match-making.

When marriage was proposed among the better class, only the virtue of the candidates, and their ability to live together properly as man and wife, were discussed long and earnestly. Such families were generally admired, and throughout the Tlingit land the aged advised the youths: “Choose your equal in caste for a life-mate, and your children shall rejoice over their birth.” With most classes such advice was indeed something more than a rustic youth could take and relish, for no social order can prevent a woman of an humble station to be born with a beautiful face and body, and a handsome man did not often hesitate when it came to having his choice. Hence, it cannot safely be said that what one person did with success was true also with the whole Tlingit nation.

Image Number: 15018

Like that which is known of all nations, men are not always alike in character—each has his own part to play in life. It is an ancient rule that his character and disposition are revealed in the man’s outer personality. In the days gone by masculine vanity, among the Tlingit people, was not entirely absent. There were men who did not restrain themselves in the illusion of physical attractiveness, they were publicly pleased with themselves; they were often heard to tell with much pride about some small accomplishments of skill and chance; likewise their whole world must know about their success in love affairs.

When romantic love became real, desire in the vain man burst forth into sonorous emotion, and he composed songs in ecstacy of his desire. With such men love was something like a great bonfire of well-dried cotton-wood—it blazed high only for a brief moment, but it would soon die down under a heap of ashes. Good women were trained to always ward off the attention of such class of men. Then a man of such character usually ended his glorious days in settling down with some woman who in like manner had seen her own day, and was at last glad to have anything that she could get, or with one who was old enough to have been his own grandmother. He then often enough longed for some change, but he had learned and knew that if he could not get along with his emotionless mate he would soon find like difficulty with another.

There were also men who cherished the women for something more than the charm of their persons. In such hearts desire became devotion rather than possession, and a man wooing a maid with such limitless loyalty pledged, in silence, his faith to her through every trial until death. And such characters, as chosen from among those admired, were well portrayed as examples in the teachings of the true Tlingit parents.

As an attempt to rectify what seems to be a commonplace idea that marriage among the Tlingit people had been customary by purchase, I think it well to offer here a brief outline of dowering the newly-weds. Though the people knew that the impediment to early marriage was poverty, in order to save spiritual love from perversion the “wait for the capable age to support” was ignored, and early marriage was generally encouraged. Wise parents sought means by which to overcome the obstruction. Hence, the custom of dower, the provident old custom which continued in its glorious development until it passed under the influence of modern life; thence, to undergo many sorts of abuse.

After putting to test that which he believed to be the right way, the best of the Tlingit fathers of the days gone by, spake and said to his son:

“I know that if you marry at this early age you will find it not an easy thing to support your wife in the comforts that she enjoyed in her long established home. But that is not a good reason why you should live apart in unnatural celibacy. Marry then, my son, and I will help you. I shall offer all that I can afford of those things which will benefit you. My own father did that for me, and I shall expect you to do the same with your own son.”

My own experience as a bridegroom might convey to the reader’s mind some idea of the system which the Tlingit employed in dowering the newly married couple. About one year after my parents called my attention to the girl who was to be my wife, I thought I was brave enough to be married, but when the final questions, “Now that you have learned her birth and personality, are you willing to marry the girl, and if you are, and she proves to be a devoted and faithful wife to you, do you feel that you will take good care of her, and always protect her until death?” were put to me, I became aware, for the first time in my life, of my cowering heart, and that most difficult word “yes” seemed to have echoed from the mountains across the bay, but it came out nevertheless, and my father only smiled when he said, “Very well.”

Image Number: 14994

One bright summer day, my aunts, cousins and all my maternal relations crowded into our house. Being the youngest and for only that moment the most important, I became a good target for all the unmerciful bantering, as the money was being counted out and other property bundled into packs, to be carried to the bride’s home, which was a mile away. All my father’s immediate male relatives were also called to assist him in his part. At last the jolly party was off, leaving me behind in company of one lonely uncle. All that was said at the bride’s home I was not there to hear, but I guess both parties were pleased, as our party appeared in a reasonable time in the company of the bride. This was only the first part of our trouble, for we had to undergo also the white man’s formality of a church wedding.

There were four different parties to be considered in all that pertained to such order of marriage obligations. They were collectively termed: “Brothers-in-law”, men who were members of the clan to which the bride belonged; “Fathers-in-law”, those of her father’s; “Sisters-in-law”, the women members of the clan to which the bridegroom belonged, and “Fathers-in-law”, those of his fathers. In an indirect manner each party contributed its share in making complete the success of the marriage, and it was deemed a great honor to be included among those who gave a start to the new couple on the trail of their independent life.

On the day following the wedding feast, in which they were the guests of honor, my brothers-in-law called for me, and I was taken from house to house, where I received gifts of all that is necessary in a man’s outfit. From one, a suit of clothes; from another, an overcoat. There were also a rifle and a shot gun, a new hat and shoes. From more distant relatives I received mostly shirts and undergarments. And their consideration for me lasted as long as I played the part of a loyal friend-brother. In like manner a generous portion of the esteem from her sisters-in-law, which once had been all mine, became my wife’s, and in turn she played her part in an excellent style, and she lived only to improve upon her character and personality, which was like a shining torch in the way of other women of her race, and until her death, never once did she fail in creating a pure friendship everywhere she went.

About four months after my marriage a number of young men of my own clan came along, carrying cross-cut saws and axes; together we went into the forest, where we felled only the choicest trees and cut them to pieces into firewood, these were hauled to my father-in-law, who was the elder of his clan. Thus I performed my first service as a son-in-law. With the Tlingit people, fire is the most important item in the comfort of life, as was expressed in the old saying: “Only by the warmth of an industrious man’s early fire tarried the good goddess of Fortune.” Hence, there can be nothing more appropriate than a supply of good firewood in rendering service to the comfort of the old man in his house.

In my father-in-law’s house, the fire burned high, and all those who came within rejoiced in their welcome to this comfort. I was led to a seat provided for me. Presently the clansmen of my father-in-law began to come, and as each came near it he held both palms of his hands to the fire, as a sign of his appreciation of being included in the comfort offered to the master of the house. When they all came in, a large tray was placed before me, as if for one who was about to partake of a feast. The master of the house then called to the youngest fellow in the party of men:

“Now, Kiyida, come and do what you feel.” The youth came forward, carrying a fine woolen blanket; this was spread out and placed on me as if to protect me against the draft from behind. “Even the smallest thing will help, my son, but the feeling with which it is offered is much greater than the gift itself,” said the elder. The next man came forward and placed some money on the tray. In like manner all the men, each in his turn presented his ” gift ” in advance of a kind remark. The tray was then filled with money, and on both sides of it were piled high other property, when the main dower was brought out, and this about balanced the whole of the clan’s share. The elder concluded by saying: “Indeed, my son, these your fathers-in-law know that you are not in want, but what they offer to you here only represents their unanimous hearty wish for your immediate success in life. Therefore you will have no feeling of displeasure.”

Image Number: 15039

According to custom, eight days following the marriage of his daughter the elder of the clan summoned not only his immediate kin, but all the members of his party, and among them distributed the property which my own party had presented, each receiving an amount in proportion to his, claim to relationship to the elder, and during the few months’ time did what he could to increase this. Some of the men may never have received any income from their portions, but would not be outdone when another returned that which he had received twofold.

All this formality of providing for the young couple was put forward in addition to that which was something like a trousseau. In some families the youth who was about to be married was well outfitted, provided with all the necessities of one who was about to begin his independent life. There has been often heard a woman to speak of her early wifehood: ” When we were married my husband had his own little chest of clothing; he had also his tools and utensils, and I also brought along my own, and we never borrowed from our neighbor.”

Thus, it was always in this respectable manner that marriage, among the better class of the Tlingit people, was provided for. Everything given by all those concerned was only for the benefit of the new couple, but there was never such a custom as buying a wife. I do not blame a stranger for making this grave mistake, for I have taken a chance in looking at my own people through the white man’s lens, and there beheld even our once glorious customs upside down.

—–

Like that which is known to all races, most persons do not have everything. In the earlier days there were only a few among the Tlingit people who were fortunate enough to have enjoyed everything that makes up a complete happiness in life. Saetl-tin, the ideal maid who was later referred to as the “Bride of Tongass”, was one born to a high caste parentage, with a beautiful face, and no wonder that Tah-shaw went a long way to get her.

It was at a modern wedding feast, after the dinner was over, the more important guests took their turns in making speeches. Some told about some comical experiences, in an effort to add more merriment to the occasion, while others imparted incidents that might affect something tending to the success of the new couple. Among these, one of the elders gave an outline of the well-known story of the marriage of Saetl-tin. At the moment I gave no more thought to the chief’s narrative than to those told by the other guests, until the late Mrs. Shotridge remarked, after we came home, that the man told the same story at every wedding feast at which he was a guest. My curiosity then was immediately aroused to learn whether the man offered this repeatedly merely to make known his own relation to the famous bridegroom, or really to effect some thought which might tend to the success of the new couple.

The first opportunity found me by the chief’s fireside. From the start I was a welcomed good listener. It was obvious too that I was the one person who should know the details of that for which our clan must have the credit. The man was not only telling his story, but at the same time very industriously handling his carving knife about the piece of wood which he was shaping to the likeness of some animal. Only when he came to an important part did he, for a moment, lay aside the effigy and use his tool as a pointer. And this ” chip and stop” went on until the narrator felt that the force of his narrative was hitting its mark, and then both image and tool were laid aside.

It was chiefly to confirm the story about the “Bride of Tongass” that I undertook to cruise the whole of the southeastern coast of Alaska, and thus acquaint myself better with the geographic conditions, while following, as near as the weather conditions permitted, the course of the famous bridal party of old. Starting from Chilkat, at the head of Lynn Canal, I made my way down along the mainland to the international boundary. On my return, in a zigzag fashion, I navigated among the islands, some of which appeared, to one in a small motor boat, like continents in themselves.

It was the month of June, a month once supposed to be the ” Moon of pups”, when the baby seals are yet too weak to protect their own heads from being crushed against rocks, but Sana-haet (god of Storm) must have just then felt like flirting with the fair goddess of Calm when we shipped to round Cape Fox. We kept our course at a safe distance of about four miles off shore, and little old “Penn” ploughed onward, fighting admirably the angry ocean. By this time my youthful deck-hand was accustomed to the rough times in a small gas-boat, and regardless of the many dangers appeared unexcited and fearless. Besides my constant attention to the engine I kept my eyes on my charts.

Steering northeast, at last, in which direction I supposed Tongass Island to lie, we ran with the wind and sea in our favor. In the midst of all this excitement I thought of the brave men of old. How well they mastered their dugout cedar canoes in these rough waters, but they had learned and understood their land and all there is in it, and in turn it understood them. The great Sana-haet was known always to be on friendly terms with one who recognized his power, therefore he would impart to the true seafarer his intentions by means of a number of familiar signs, and a true seafarer was not often heard to tell about like experiences which I had to undergo during this particular cruise.

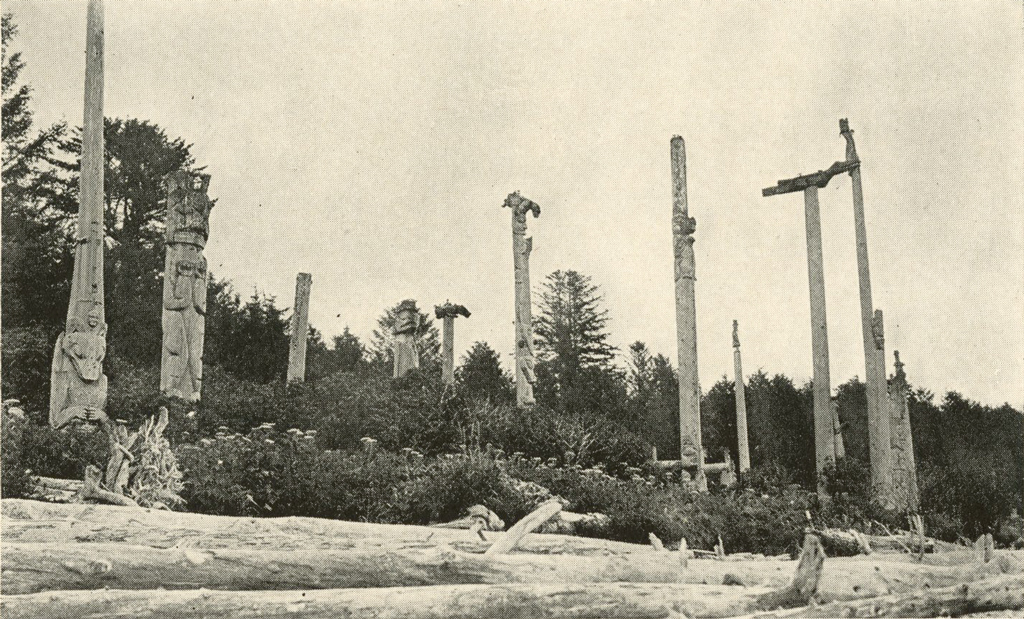

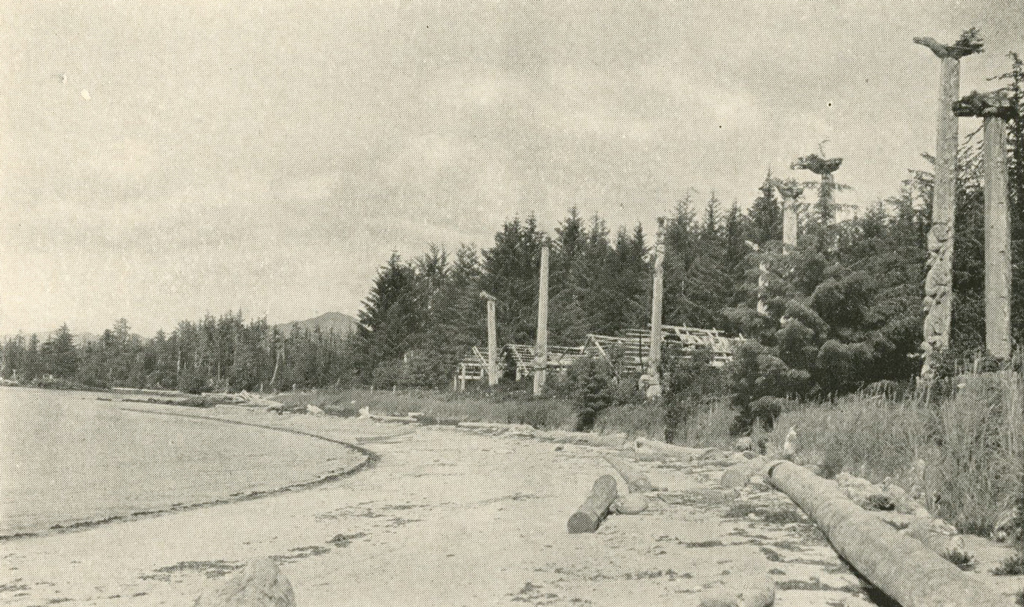

In my lookout for the location of the old Tongass village it was difficult to pick the right island among many others, as the evergreen forest on these was blended into that of the main land. Through the mist of the spray I saw that which appeared like withered stalks of giant wild celery. Half a mile closer, through my spy glasses ; I at last made out what these were—totem poles, the principal objects of interest now in most of the abandoned old towns that I visited on this trip, relics of the aboriginal life of the region. Silently they still stand, sentry-like, each telling its own story.

Image Number: 15038

The first view of the historic old town now abandoned was depressing; I could not avoid the feeling of gloom, especially in that cold gray afternoon and after experiencing, only a few days before, the rush and bustle of the lively modern towns; from the deck of our launch we had watched the concrete buildings and the great fish depots disappear behind an island and heard for the last time the cheery roar of the street traffic. We made fast close to a sandy beach across a narrow passage from the village of Tongass, and landed in front of it in a small tender.

When I came up among the many totem poles, there I looked along a streak of a well-beaten-down ground, which for nearly a century had refused the staunchest weed to take root, an evidence of the town’s main road, a street which seemed to listen still for the tread of the vanished chiefs. There is now only the wailing of the wind in the totem poles to remind one of the proud voices that once echoed there, and the far-away pounding of the Pacific Ocean to recall to mind the sound of the drums of the jolly dancers that passed here.

Into dusk I sat there on a fallen post thinking of the things they did there; sometimes I sighed and sometimes I smiled. Once again I thought of all that I had learned about the manner in which chief Negoot performed his part in the play of life, in order that those who follow may know that they were people also with their own pride, and to myself I repeated that never-to-be-forgotten story about the behaviour and magnanimous marriage of his beloved daughter.

For the benefit of the girl who believes that in every true woman’s heart there is hope and longing for something nobler and better, and that in the blind searching after an ideal some women are made better, the story about Saetl-tin is repeated.

The story follows, as it is made up from the versions of the different geographic divisions of the Tlingit land.

What Took Place in the Northern End

In the old perilous days, in Grouse Fort, the land of the Kaguanton, on a promonotory, sat an old man much buried in thought, his worn face resting on the support of his forearms. In his day the old warrior had fought the fight of his forefathers. Thus, from youth he had contributed his share in building up the honorable position of his party. But now age had overcome all hope of taking an active part in the game of life. Hence, none else could he do but give counsel to the young. He was thinking not of the then impending war, but of the thing which, in his own mind, bore a weight which was equal to that pertaining to the clan affairs. The heir Tah-shaw had spoken of marriage; the youth had made known to his own mother the maiden of his choice. But Saetl-tin, the maid, was of a division far away. Yet the old wise head knew that distance was never an obstacle where a stout youthful heart was fixed on a fair maiden.

“What has an old man, grown grim and gray, to do with the wooing of a youth? . . . After all it might be well to let the lad do what best delights him, and come what may of this venture he alone shall feel.” Long in this position sat the old man, wistfully gazing on the peaceful ocean that stretched away into the far southern horizon, still thinking. ” The lad should wed a maiden of his own people, but he would go to the far south for a handsome stranger. There was a war between her people and us, and there are wounds that ache and still may open. Yet if the lad should wed the fair Tongass maid, that might unite our hearts once more in peace and the old wounds be healed and in time forgotten.”

In the meantime, to and fro, by a stream of water in the deep forest, strode, with a confused air, Tahshaw, the rightful heir to chieftainship of the Kaguanton clan, also buried in thought. His father’s father, the chief, had spoken his counsel, and spake in this wise:

Image Number: 15032

“My grandson, your feeling is to take to yourself a wife. It is well that one in your position should marry, but one should choose a woman who shall be like a shining torch on one’s path of life. You have had your training, my lad, and now is the best time to use your best judgment about whom you should take for your life-mate. We are now at the beginning of our history, therefore each one of us should take a firm hold on only that which will add to the achievement of true men.

“Our ancestors were a people with a history which is not to be admired by wise men—they appeared to have led much the same life as was natural to their station. But none the less, my lad, your turn to do noble deeds is in your veins. One of the main objects in a good man’s life is to bring forth children with blood which is not tainted. I am not saying that the woman of your choice is below you, for her father is well known not only to us, but his name has been heard far and wide. But you have been fortunate, indeed, to have before you so many good maidens to choose from; here at Grouse Fort are daughters of the best men of our party; also in Chilkat are brought up maidens who do justice to their peerage. Yet, withal, your mind seems to lie on one in the far land.”

The youth paused and sighed, and looked up to the clear sky as if about to supplicate. He loved the maid of his dreams, and was determined to win her for his wife, and nothing his wise grandfather, the chief, said could make him change his mind. Of course it was natural for the young man to be thinking and dreaming about the beauty of the Ganah-adi maid whom he had met in Tongass. He thought of her only as an ideal mate; he seemed to hear her low soft voice in the murmuring of the stream of water, and in the sighing of the tree-tops, as he went about in the solitude of the forest.

The day for the start of the Tahshaw party from Grouse Fort was well chosen, it was one in the wake of Sana-haet (Southeastern Wind), and the spring moon was then appearing only with half-face; the tide reach too was getting shorter, and the way was clear for Hoon (North Wind) from the north, which on that day, under the cloudless sky, blew forth to give aid to the speed in direction of the land of the “Children of Tequedi”.

Tongass proper is located in a bay which is now known as Tamgas Harbor, at the southern terminus of Annette Island, and in the coast and geodetic survey, the old town of Kadoqku which is located on the shore of Nakat Bay, around Cape Fox, has been mistaken for it. From the northern shore of Icy Strait this was, indeed, a great paddling distance, but distance was never an obstacle for those old-time men when they went for something important.

With the people of Tongass first lived Aun-yatki, “Children of the Land”, persons who lived for disciplining the moral and intellectual nature of their people. Without such persons it is likely that we might have become, once more, denizens of the forest, and never to be heard of. Here in this land of our ancestors, personal modesty was early cultivated as a safeguard, together with strong self respect and pride of family and race. This was accomplished in part by constantly bringing out the child before public eye. His entrance into society, especially in case of rich parentage, was often publicly announced in a formal celebration called Yat-da-tiyi, “Event about Child”.

Image Number: 14991

Among the women there were rules that were not known to men, except to fathers of daughters perhaps; the women knew that when a maid passed from childhood to womanhood, she never knew how to take her first step upon such a change. So it became the duty of those who had passed the climacteric to take her in hand.

In old days when a girl reached the age of puberty, which is usually about fourteen, she was immediately taken in hand by the mother or an aunt. She was secluded for from one to four months without ever appearing in daylight. During this period of confinement she had to undergo a number of observances supposed to affect her future life. It was at this time too that the maiden was taught all the necessary duties of a true wife, as well as her domestic obligations.

Saetl-tin, the ideal maid, was among the first who were called the ” Children of the Land”, and was brought out before the public eight times. But the maid first became famous in the Tlingit world through observing to the full extent the customs imposed upon a girl at puberty. The young lady carried her part to an extreme when she, upon learning of her wedding moon, had her whole body kept covered with the soft skins of the underground squirrel, pasted on with pine-pitch. This was done to bleach the skin of the body.

What Took Place in the Southern End

When the Grousefort party carrying Tahshaw, the prospective bridegroom, approached the entrance to Tongass, they were met by a darkened smoke of burning grease which filled the whole bay like fog. They must have been informed of the position of the travelers from the north, whereupon the whole town started to pour oil on the fire. This was a sign of prosperity, and done to impress upon the mind of the northern people that they were visiting the land of plenty.

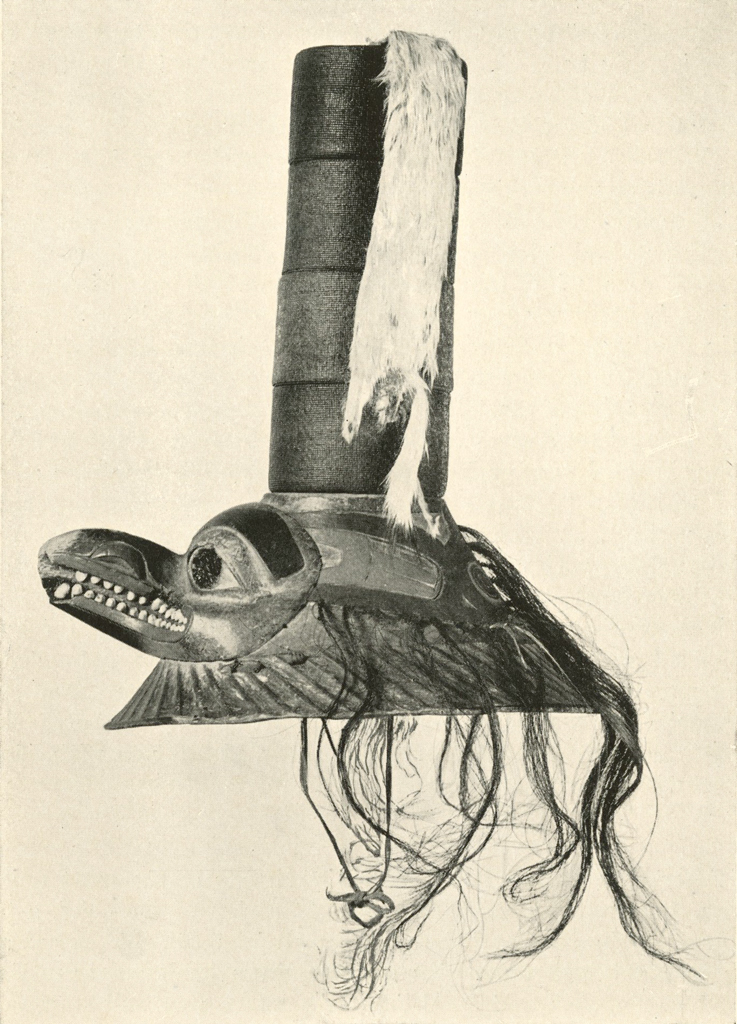

The party arrived before the town. In the middle of the great war canoe, on a raised platform, was seated Tahshaw, the prince from the north land, adorned in rich fur; on his head he wore the Ganook Hat (page 147) which represents the most ancient being in Tlingit mythology. “Who is there in the whole Tlingit land to boast of a possession greater in character than the Ganook Hat?” The canoe backed upon the sandy beach of Tongass landing. The people joyfully bade them welcome, and at once invited them to the house of Negoot. The chief’s men then led the visitors into the house, and there they were seated on cedar mats and the softest fur. While they were being fed the townspeople came in to see the strangers from the north land.

The arrival of the Tahshaw party at Tongass was not a surprise, for it had been expected; therefore the people were well prepared to receive the young nobleman. The visitors were detained in town for four days, celebrating the festivals put forth by the chiefs of the different groups. In their turn the visitors also entertained the townspeople.

The morning of the fourth day was the time set for the wedding. In the presence of a great crowd of people the elder of the Tahshaw party told the House of Negoot the purport of their mission; told it the wish of the House of Tahshaw. And the speaker concluded in this wise: ” . . So Tahshaw, your descendant, has now come to your daughter, with an offer and proffer of marriage, made by one whose blood is not tainted, and who is true.”

Negoot did not answer at once, but sat in silence for long. He looked at Tahshaw and thought, probably, what a handsome young man, and how proud he would be to call him son. And then he thought also of his lovely daughter, how well he loved her. Then he made answer very gravely: “Yes, it shall be as you wish, if the maiden wishes.”

The Wedding

After both parties had been satisfied, one of the most unique marriage ceremonies was performed: At a sign of the chief, a precentor started a song and the great crowd joined in the chorus, and sang in a subdued tone. At her cue, from behind a beautifully carved screen, appeared Saetl-tin; on her face was well stamped a facial design representing “Star-fish, torn to pieces by the Raven”. With the finish of the song she disappeared, but only to appear again to the accompaniment of another song, and wearing another design. In this manner the bride appeared eight times in succession, with eight different designs, each accompanied by its own song. The second was a design called Woosh-yik-kitli, (representation unknown); then followed the ” Tears of the Puffin” ; the ” Jaw of Killerwhale”; the “Ears of the Wolf “, and the remaining three have been forgotten.

The Kaguanton clan, to whom they were presented by the famous bride, put the facial designs to a good purpose in later years. The “Ears of the Wolf” was often mentioned in connection with the heroic feats of Neech-kuwu, the fearless Kaguanton warrior.

After the conclusion of the first part, there was a brief intermission, while the bride made some changes. Presently the bride passed out, attended by well selected young female slaves, eight in number, and the maiden seemed more lovely as she stood there. There never was a more complete beauty than this maid of Tongass. Her eyes were long, sort of brownish black and languishing; her hair, also of the same hue as that of her eyes, hung down to her heels. To this must be added the item of a skin, pure and like a finely tanned skin of the doe. They say she was rather small in stature, but a well developed body offset the childish appearance.

Tahshaw himself found that the maiden of his choice was no debtor to the promise of her girlhood. She had amply fulfilled her obligations. A more sparkling bronze beauty he had never beheld. To all there was no sign of arrogance, but there was about her the air of humility, as one trained to render service only in silence. Shy and appearing neither willing nor reluctant, her head slightly bent forward and her eyes fixed on her linked hands, Saetl-tin went to her husband, softly taking the seat beside him, while the whole of Tongass looked on with mixed admiration and pride. Presently Negoot, the lord of the town, spake, very briefly, his part:

“Now, my daughter, it is your own heart which turned to this man who is now your husband. He is your peer indeed, therefore you should never be the cause of his shame; always be a good wife to him. Henceforth, you will follow him until death. And may the good goddess of Destiny guide you in the footsteps of those women whose beings have been a delight in their world.”

When the father concluded, the maid seemed to relax, and her face changed color, as if suppressing a delight. Again there was a brief silence, and Negoot lowered his head as if to indicate the conclusion of his part. In like manner the bridegroom sat there in silence, but appeared rather embarrassed when the elder of his own party spake his part, in this wise:

“And you, Tahshaw, you take this maid for your wife—a life-mate. Henceforth, together you will proceed on the trail of life. It is the man’s part to be the guide, and it is his chosen course that the woman follows him. If he chooses the right way to success there she also succeeds, but if he deviates, though she may be aware of the wrong turn, yet she follows him, because of her faith and devotion. Shame, when it comes to him, is the man’s own seeking, and disgrace knows where it is due.

“Now, Tahshaw, you have taken the lead, and to follow is one whom you esteem the most, your peer indeed. Therefore, there can be no leadership so sacred, no responsibility so noble. You are to be a true and devoted husband. For her sake will you stand firm, and drive off any evil which might threaten to harm, and have your heart like an invisible guard always hovering around your wife. If you succeed in this sacred duty to old age, none but happiness shall be your meed. But once you fail, your own shadow shall taunt you to your last days.”

In their hearts, silently, the youth and the maiden repeated the words of betrothal; taking each other for husband and wife in the presence of their elders. Little did they know that they were then laying a foundation for that which was to be the way of the best of the Tlingit nation, and the laudable custom of our land.

After the solemn part was over, there were brief speeches, expressions of good wishes for the new couple, and all these incidentally changed into a revel, and the people were all happy. As they passed out from the house they gathered and crowded about the town, questioning, answering and laughing. That night, from the sky the great moon looked down at them and filled the town with mystic splendor. Even those brave warriors who had departed to the land of the Kiya-kawu (Aurora Borealis) appeared in the heaven to celebrate the occasion.

Negoot made a great feast in honor of his daughter’s wedding, and sent messengers through the town, announcing at each doorway the invitation: ” To the Bear House, you and the inmates of your house are called to partake of the maiden-lunch.” Everything was now ready, and into the Bear House filed the Tequedi guests, each carrying his own bowl, most of which bore a carving of an object representing the owner’s totem. When they were all seated, there was a brief speech, announcing the nature of the feast. And then Negoot, the speaker, called to his nephew (sister’s son), who was his heir, to serve the guests, and a party of young men and women came forward to wait on the people.

There were choice fresh fish and the flesh of the deer in plenty, also berries of different kinds, sweet and healthy. It was a good feast, and every one ate heartily, except, perhaps, Tahshaw and Saetl-tin—their appetite for food seemed to have been overwhelmed by popularity, and the youthful couple sat there harrassed and appeared as if held at bay by a revel which seemed to be let loose, all at once, after a suppression.

The Dance of Friendship

The feast was about finished; the more important guests were then settling back comfortably, smoking their pipes, when a song was heard without. It was a Haida love song, chanted in perfect unison by many voices to the beat of a drum. Presently the door was thrown open, and the drummer appeared at the entrance dancing, his body moving in time with the beating of his drum. He was followed by a long line of dancers, women and men, who were all dressed in various styles of costumes their faces painted with red ochre and powdered charcoal, the tops of their heads sprinkled with cut down of the eagle, making the jolly dancers look as if they had come through a snow-storm. They all looked well indeed, and each one appeared as if there had never been a happier dancing than the one he was performing. This is a proper spirit when one is to enjoy what one is doing.

About half-way of the line of dancers the principal dancer appeared. He moved into the hall backward as if to show first the design of the robe he wore; jerking his head slightly to one side, as if testing the time of the song. When he backed within across the breadth of the upper terrace of the floor space, still moving gracefully to the tune, he gradually made a turn, and Kuh-teech, the greatest solo dancer among the Tongass people, faced his audience.

Kuh-teech wore a robe of buckskin, with the owner’s totem well designed upon it; it was trimmed with strips of fur of the sea-otter, from his waist hung a covering something like a short apron, with fringe tipped with beaks of the puffin, which rattled to produce a sound like the burning of fresh spruce bough. In each hand he held a short stick with tassels of more of the beaks, rattling at each end. On his head the dancer wore a headdress of the Taw-yat (Flathead Indians). This was beautiful, it was said. The abalone shell ornamentation on it shone like sparks of the night fire; from its top end stood the well-arranged long whiskers of the walrus which swayed like full grown cattails in a wind-storm; from the back hung a long trail of skins of the ermine, which also continually swung about in the air.

The skilful dancer timed his movements well enough to make his turn in time to take up the pronouncing of the words to the final verses, and the chorus kept up to his lead. The song was cleverly composed, expressing their rejoicing over the creation of peaceful love between the two great clans, the bride’s and the bridegroom’s. It was a beautiful song.

When all the dancers came within, the second or the real dance song, which was faster, followed immediately the entrance song. With this the dancer ducked like a slightly wounded halibut, then out of the cavity of the headdress emitted a great puff of well-cut down of the eagle. As the dance was heated up, like the first light snow of the season, this symbol of peace began to settle softly upon the assemblage, its softness seemed to soothe all prevailing hard feelings. And the people were much pleased and praised the great dancer.

The song and the dance were ended, and the dancers stood panting like hunters recovering from the effects of a long chase. In a labored manner Kuh-teech uttered a few words, addressing the bridegroom’s party in this wise:

“Not to surprise you, oh children of Ganah-taedi, do I perform that which might agitate your peace of mind, but rather to express, in this lame fashion, the happy feelings of the children of Tequedi. At this moment, like the warmth of the sun, do they feel your honorable presence, and all together they rejoice in this.”

With sincere smile the elder of the bridegroom’s party answered: “Ho, ho (an expression of gratefulness), it is well, oh Children of Tequedi. In truth, into our hearts come home your words, and we feel it like the down which now settles on our heads. When we return to those who await us upon our land, we shall have in our possession to bring out before them, not only that which is good to the taste, but more of that which will create comfort in a true man’s heart.”

Thus, only a song and a few words uttered by true men acted like a great landslide, sweeping away all that which grew by years of struggle. Indeed, there was much truth in the old saying: “Put your full strength in swinging your club of fire, you cannot expect your opponent always to fall without a return, but put on him a handful of the softest down, even a heart like stone will soften.”

The Wedding Journey

There is always an end to every nice thing; so it was to the Tongass people when the day on which the beautiful Saetl-tin was to take leave from among them dawned. On the shore, behind the waiting canoe, were assembled friends, young and old, saying their last few words. The young girls threw their arms about Saetl-tin with an expression of farewell, and the girl’s mother returned many times after she had embraced her, to embrace her again. How much she loved her daughter, and how difficult it was to let her go with strangers.

There in the canoe were men, hearty and strong, each seated erect on his own end of the thwart, ready and eager for a start. They seemed to be anxious to put an immediate distance between themselves and what was to be left behind. In a section, one next to the bail-hole, which was all lined with rich fur, were placed the bride and the bridegroom. And at last, Saetl-tin, the most beautiful bride, was aboard, the great canoe was shoved off shore, and at once the paddles began to sway together, pushing behind the waters of Tongass, as with a feeling of pushing everything else to make way for that which awaited them. The people still stood on the shore, thinking, perhaps, that out of their midst was then borne away one who had made them feel proud only with the wealth of her being.

On the porch of his house stood Negoot, sadly watching the canoe as it went out to sea. At last it was lost to view, and the chief went back into the house, murmuring to himself and saying: “Thus it is our daughters leave us, just when they have learned to love us; when we are old and lean upon them, comes a youth, beckons to the fairest maiden, and she follows where he leads her, leaving behind only loneliness.”

Lost in the sound of the paddles was the last farewell of the Tongass people. Soon the canoe was out on the homeward course, and the two sails were set to the fair south wind, blowing steady and strong in the warmth of midsummer sun. The great canoe gradually picked up more speed; plunging forward like a living mammal, raising its head after plowing into the long rolls of the ocean as if to show its pride of having the honor of being trusted with the important passengers. Immediately in the wake of the bridal canoe came one which bore the dowry of the bride, well manned by slaves, under the command of a man who knew well the arts of navigating.

All creatures seemed to appear, each to offer its share in making whole the success of celebrating man’s happiest moment in life. From all directions came rushing the dolphin and the porpoise, swiftly slipping into the procession. Overhead the sea gulls shrieked their delight in keeping up. A duck, from a deep dive, rose to the surface only to flutter aside in flight to make way for the violent rush. From the clear blue sky the great sun, benignant, looked down upon the party in mid-ocean. To Saetl-tin and Tahshaw love was then like this sunshine, and in their hearts nothing remained to cast a shadow. Thus, in such a benign atmosphere the most wonderful journey sailed on to the land of the Kaguanton.

A Welcomed Stranger

When the bridal party arrived in Grousefort, a party made up of the handsomest men of the town met the canoe at the landing. The young men went forward to carry the bride from the canoe, but to their disappointment they were ordered to stay clear and make way. To the surprise of the northern people, the maiden, of whom they had heard only as one who could not forbear blushing when she observed by a man’s look that she had been an object of some attention, unassisted, stepped off on to a box, bare-footed, and as was intended, all those present had a glimpse of the most beautiful legs. At that time the women were clothed down to the very wrist and up to the very chin. The hands and face were the only samples they gave of their person. But since the arrival of Saetl-tin among them, some nice discoveries were made in their complexion, and mode of dressing.

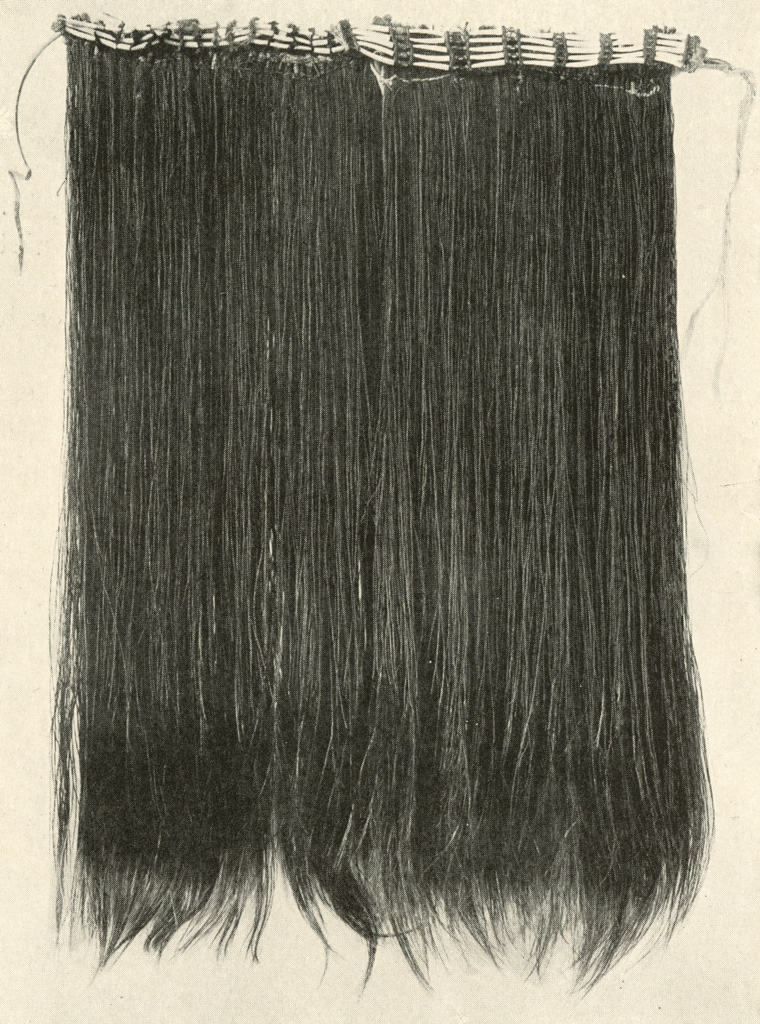

In the home of her husband, Saetl-tin found everything peaceful and her reception very pleasant. The old persons who had objected to Tahshaw marrying the strange maiden, lest she should be idle and proud, found, however, that Saetl-tin’s fingers were skilful, and did things for them regardless of her station, and that she was kind and gentle, even to one who was not in her class. As an evidence of her willingness to sacrifice for those whom she loved, we have only a part of Saetl-tin’s long hair (page 154).

At one time when her husband was appointed as director of a great convention, the lady could not think of anything more appropriate to offer her beloved husband in his honorable office than that which she deemed her most esteemed possession, her beautiful long hair. Saetl-tin had this cut off at her waistline, the tips were worked into very fine braids, and these almost countless braids were formed into a wig-like headdress to be worn by Tahshaw on the great day of his first appearance. The UNIVERSITY MUSEUM has been fortunate enough to obtain also this specimen which must have required every ounce of patience of the old-time Tlingit woman.

Saetl-tin and Tahshaw truly loved each other, and as they grew old it made no difference to either whether the other was old and ugly, their love remained the same.

Thus, it was our ancestor Tahshaw who brought the loveliest of all the Tongass women, Saetl-tin, to his home, to be like the sunshine for his people. He had brought not an idle maiden, for Saetl-tin proved to be one whose hands and heart were ever ready to serve her beloved husband’s people. To her old age she continued her pace on errands of mercy. And after those who had preceded her to the land of souls had reclaimed her, her name and the memory of her beautiful character remained for an inspiration, even on to our time.