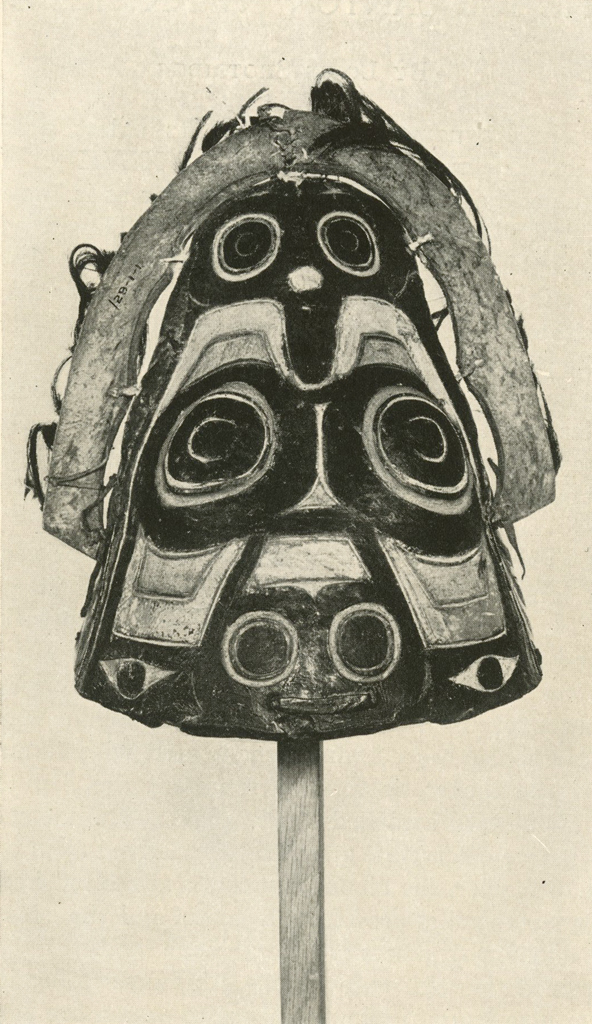

AT last the Kaguanton Clan let go its oldest possession, the “Shark” Helmet (Plates XLVII and XLVIII). It is a very unique and ancient specimen, and so far as is known, the only one of its kind which existed in the land of the Tlingit. The helmet is made of the thickest part of the hide of the walrus, evidently shrunken, by a heating process, around a wooden form after the two pieces had been sewed together; it was then carved after it had thoroughly dried. The projecting parts, such as the lips of the shark and the eyes of the figure on the back of the helmet, are forced out and carved in relief, leaving the original surface of the hide; this surface was carved away from the part we recognize as the face of the fish. The hide is about one-half of an inch thick where the deep carving is executed.

There is sufficient evidence to believe that this very old piece was made long before steel tools were introduced into the Tlingit land, yet the clear cutting, said to have been done with an incisor tooth of the beaver and stone, is done in a manner which it is hard to believe could have been accomplished successfully with any but a well-edged modern instrument. The strip of the hide which encircles the head-piece, also carved, and ornamented with human hair and feathers of the flicker, is said to represent the Fish Hawk, with the beak of the bird attached at the peak. The helmet is painted with pure native colors; the greenish blue derived from the covelline, a sulphide of copper, the black from coal and the red from ochre. A certain kind of shell is used for the teeth, and the eyes and mouth are ornamented with pieces of blue abalone shell.

I obtained this old piece for the Museum’s collection from the last of the house group, the members of which are known as the founders of the Kaguanton Clan. When I carried the object out of its place no one interfered, but if only one of the true warriors of that clan had been alive the removal of it would never have been possible. I took it in the presence of aged women, the only survivors in the house where the old object was kept, and they could do nothing more than weep when the once highly esteemed object was being taken away to its last resting place.

The Kaguanton, in its early history, was a party of men who were never afraid of adventure. They were hardened men, good fighters, and good loosers in war. They were noted for their warlike nature, but they were no more savages than the present time warriors who fight for that which they believe to be just. In the record of these old-time fighting men, honour seemed to have predominated even above wealth, therefore good traders were not many among them. They seem to have shown a dislike for being burdened with accumulation of property, yet there never was anything too good for them.

The abandoning of the Shark Emblem is one instance which shows the Kaguanton dislike for anything in the nature of indolence and cowardice. As it was told in the story about the ” Midnight Council”, when chief Stuwuka said, after being reminded of the Shark Emblem: “If this Shark is to maintain its rank in our history, why does not this indolent animal appear in a true man’s dream? Cast out from your minds, Kaguanton, this cowardly fish which, with its rows of sharp teeth, would only slink in presence of danger, and only take advantage of a helpless being. Think of the ‘Wolf’ now; he is bold and will fight when necessary.”

The council referred to took place at Grouse Fort, long after the organization of the Kaguanton Clan, when the Wolf Emblem was in question. It was at this time when, true to its nature, the Shark quietly sank to the bottom of the chest of relics, only to make its appearance when occasion called for so doing. Thus, from the beginning of its history, the old object existed in an indifferent attitude, because of lack of interest on the part of its assumed owners. The helmet was made for Yiskahua the warrior, who was entitled to make a public exhibition of his helmet during the ceremony of dedicating the Kawagani Hit, “Burned House”, the first council house which was founded by Yisyat I. At this time his party resided at Sand-mount Town, an old town now abandoned, located in the neighborhood of Cross Sound, a waterway between the mainland and the northern terminus of Chicagof Island.

In the beginning the name Kaguanton was applied to a house group which eventually developed into the greatest clan of the Shun-goo-kaedi moiety of the Tlingit nation. Being without necessary tools the old-time builders employed the fire in reducing the main timber supports for the new council house, to uniform sizes. Thus, the name of the first house of the clan, from which the first group took its name, Kawagani-hit-ton, “Burned-house-inmates”. Very quickly this very prolific group developed into a clan which spread very widely, and to this day are met almost everywhere, not only in Alaska, but there are a few in Europe, China and Japan, even here in Philadelphia. But these modernized men are not at all like the true Kaguanton—their spirits have been much impaired by too much comfort.

Even though the “Shark” had failed to maintain its rank among other emblems of the clan, it was looked upon with respect, because it represented the efforts of the men who founded the party. Therefore, like any other important object, a true Kaguanton guarded it with diligence. It is true that the modernized part of me rejoiced over my success in obtaining this important ethnological specimen for the Museum, but, as one who had been trained to be a true Kaguanton, in my heart I cannot help but have the feeling of a traitor who has betrayed confidence.