THE Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the University Museum started its ninth season at Ur on November 1, 1930, and continued in the field until March 20, 1931; the season was a long one and a larger number of workmen than usual was employed, the average for the first three and a half months being two hundred and eighty and for the remainder of the time two hundred; the amount of actual excavation done was in consequence greater than in any previous year.

Image Number: 149979

The staff consisted of myself and my wife, who as usual was responsible for the drawings and assisted in the field-work, and Mr. M. E. L. Mallowan, who for the sixth year in succession acted as general archaeological assistant; the epigraphist was Mr. Chauncey Winckworth, Reader in Assyriology at Cambridge, the architect, Mr. J. C. Rose, and Mr. P. J. Railton came as junior assistant in field work. My Arab staff was unchanged, Hamoudi being as ever in charge and excelling himself in the amount of work done, while his three sons, Yabia, Ibrahim and Alawi acted under him as junior foremen, the first doing all the photographic work also.

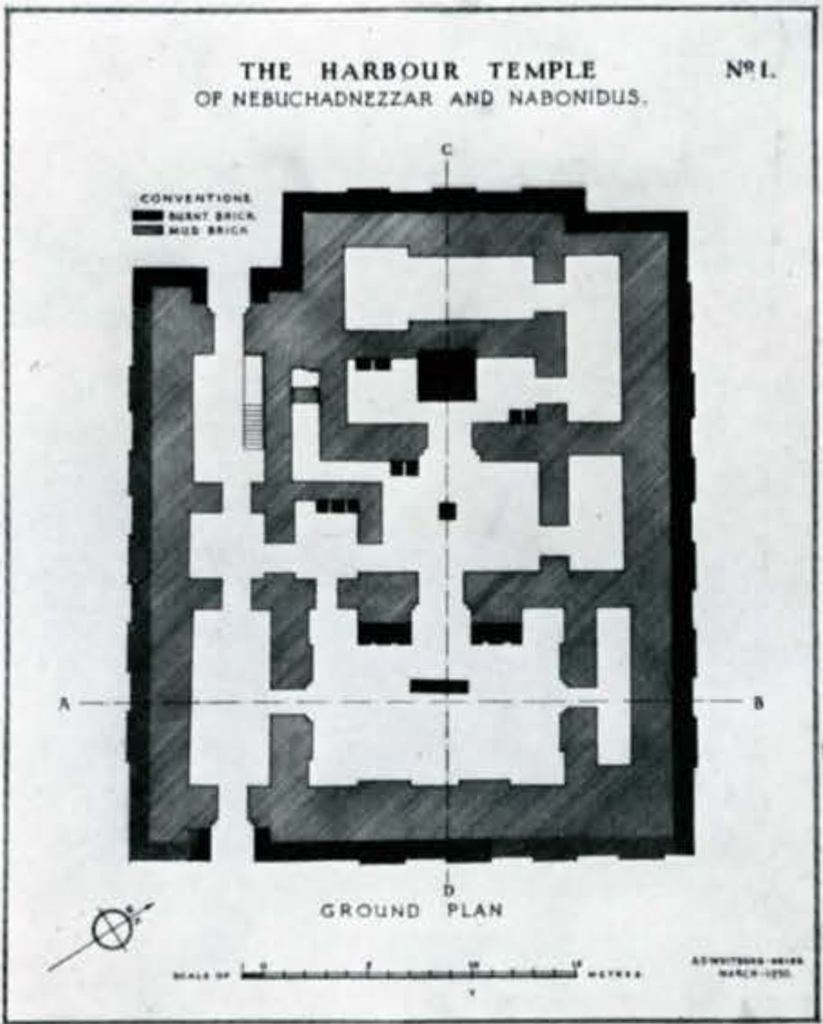

The main sites excavated were the royal tombs of the Third Dynasty, a palace built by Nabonidus for Bel-shalti-nannar near the North Harbour, and a large area in the south-east quarter of the city which gave us house remains of the Larsa period and also of the Neo-Babylonian. Apart from these, two smaller tasks were undertaken. Inside the Temenos enclosure there is a considerable area of low-lying ground extending from the temple E-Nun-Mah along the north-east boundary wall where it had been supposed that no buildings of historic date survived denudation; a trial trench driven across this has brought to light fragments of walling which, if followed up, should go far to fill in a blank patch in our plan and complete our knowledge of the topography of the Temenos; this information having been obtained, the thorough excavation of the site was postponed until next season. A shaft was sunk in front of the Ziggurat in the hopes of finding remains of the pre-Third Dynasty temple of Nannar. It was found that the Neo-Babylonian work had destroyed all historic foundations on what had been from very early times a high artificial platform the floor of which, made of plano-convex mud bricks, was discovered almost intact together with its containing-walls; the latter were remarkable in that the mud bricks of which they were constructed were of two types, small plano-convex bricks, often laid on edge and sloped in herring-bone fashion, alternating with large rectangular bricks Iaid in flat courses; the walls would therefore seem to date to an intermediate period when the old rectangular bricks were being replaced in fashion by the plano-convex bricks which characterise an epoch between Jemdet Nasr and about 2800 B. C. The following-up of the prehistoric Ziggurat enclosure was left over till next season and the shaft was driven down to water level. Below the plano-convex pavement only one phase of construction could be traced, with scanty wall foundations and remains of a mud floor thickly littered with the clay cones and stone disks used for wall mosaic. In the stratification some difficulty was felt at first by the occurrence in the higher levels of quantities of painted al’Ubaid pot-sherds which lower down failed and gave place to wheel-made wares and to Jemdet Nasr types; a close examination showed that the al ‘Ubaid fragments had been deliberately mixed with the clay of the bricks and more especially with the mortar of the plano-convex and rectangular brick period, a phenomenon which is found in corresponding strata at Warka and can only be explained on the grounds of religious archaism. Towards the bottom of the shaft al ‘Ubaid wares occurred freely in their true horizon; with them, at 11.0 metres depth, there was found a twisted fragment of gold wire (square in section and cut, not drawn) which is our earliest example of the working of precious metal. A fuller description of this site also must await further excavation.

The Royal Tombs of the Third Dynasty

At the close of the season 1929-30 there had come to light, at the northeast end of the prehistoric cemetery, part of an extremely solid and well-built wall of burnt bricks set in bitumen, many of which bore the stamp of Bur-Sin. The building lay considerably lower than the palace of Ur-Engur, not far away to the west, and this fact, together with its proximity to the cemetery at a point where graves of Sargonid date were at unusually deep level, gave grounds for hoping that here might be the tomb of Bur-Sin. At the beginning of last season a start was made behind the exposed length of wall and it was at once found that the original building had, after its destruction, been overlaid by private houses of the Larsa and subsequently of the Kassite periods, and that these in their turn had been cut through by the foundations of the Temenos wall, of Nebuchadnezzar. The whole of this part of the Temenos wall, of which hitherto only the outer face had been traced, was now excavated and where necessary cut away, and a fairly consistent section of town planning was secured before work could be carried down to Third Dynasty levels. As the excavation proceeded it was discovered that the Bur-Sin building first found was really but an annexe of a much larger building which the brick-stamps in its walls assigned to Dungi, Bur-Sin’s father (c. 2260-2220 B. C.); south-east again of this there was attached a second annexe also put up by Bur-Sin (c. 2220 B. c.); certain features of the brickwork make it probable (though not proved) that of the two annexes, the southeast is the earlier in date, a hypothesis which would agree very well with the striking similarity between the ground-plans of this and of the Dungi building and the irregularity and smaller scale of the north-west annexe.

In spite of irregularities, however, all three buildings alike are definitely modelled on the private house of the period. In each case a front entrance on the north-east wall leads through a lobby into an open court, surrounded on three or four sides by chambers, which in some instances correspond to the chambers in an ordinary residence. The difference lies in the scale of the building and the solidity of its construction, the richness of its decoration, the fact that it was of one story only, and in the appointments of some rooms, to be described later, which are never found in private houses. The discovery that under each of the three buildings there are great vaulted tombs seems at first sight to make the analogy with the private houses more complete, but against this we have not only the unexampled size of the tombs but the fact, to be explained later, that here the superstructure is both in construction and in importance secondary to the tomb, whereas in the private house the residence is the chief element and the tomb in every sense subordinate. A detailed description will supply the evidence for the above statements and for our further conclusions as to the nature of the buildings.

The Dungi Building.

This is practically a rectangle measuring 35 metres in length by 27 metres in width, the thickness of the walls being as much as three metres; all the angles were rounded externally. The south-east side was not continuous but had a bold salient for the greater part of its length, the south angle of this too being rounded. The wall face was relieved by shallow plain buttresses, the only exception to this being on the north-east side where the main entrance door was flanked by buttresses decorated with T-shaped vertical grooves such as are normal in religious buildings, and the corners of the jambs are resolved into a series of reveals. The entire north-east side of the building was much destroyed; it was clear from the way in which the walls were ruined down from south-west to north-east and from the stratification that the mound of debris which covered it after the Elamite destruction sloped in this direction and the more exposed walls had been pulled down by builders in search of bricks, probably in the Larsa period; on the north-east then the walls seldom rose above floor level and sometimes even their foundations had been dug away, whereas on the south-west they were more than two metres high. All walls were of burnt bricks laid in bitumen; up to the height to which they now stand there is no sign of any transition to mud brick, but the character of the debris filling the rooms would point to the upper part of the walls in this building, as in the private houses, having been of unbaked bricks; but this is not certain, since a great deal of the filling is of mixed material, and the ruin seems to have served as a dump for the disposal of rubbish.

Figure 1. The Courtyard to Dungi’s Building looking East to the doors of Rooms 1 and 3.

Image Number: 191722

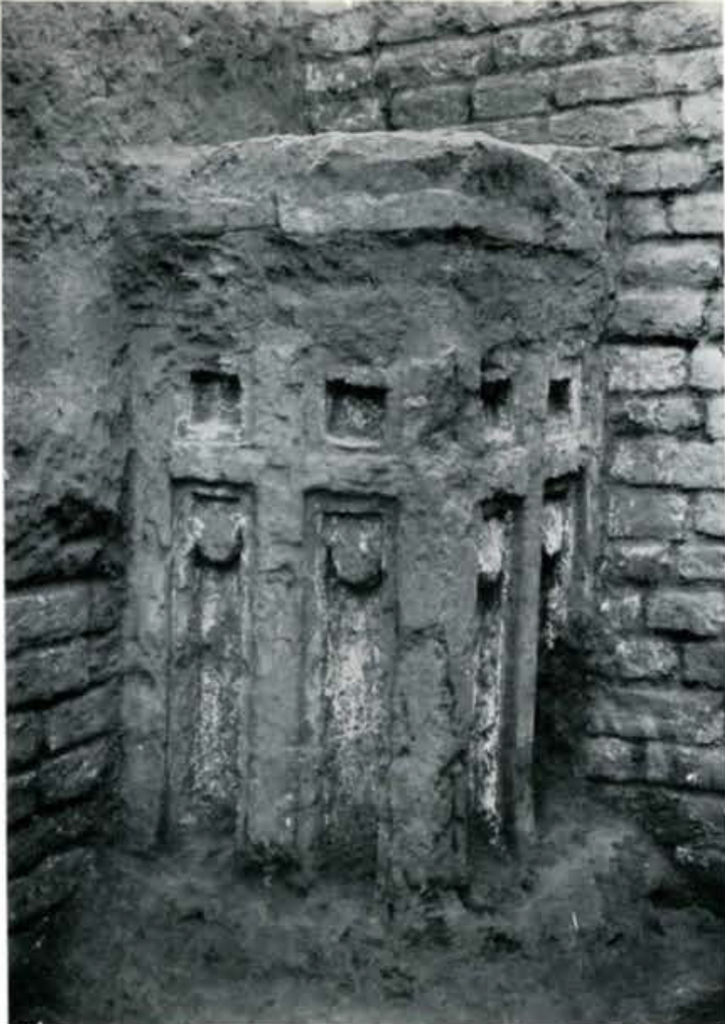

Figure 2. Room 5 in Dungi’s Building, showing Grooved Altar.

Image Number: 191688

The main door leads through a small brick-paved lobby 1 into a large open court 2 [Plate XXXII, 1]. Originally this was brick-paved, sloped to the center where there is a drain of terra-cotta pipes running down into the subsoil; a diagonal line of paving-bricks accentuated the slope of the surface and lead the water to the drain mouth. An edging or narrow platform of brick, raised about ten centimeters, ran round the north-east, south-east and south-west sides; over this, against the south-west wall between two doorways, we found the remains of a brick altar with shallow bitumen-lined channels along the front of it, exactly like the altar in zoom 5. In the west corner of the court, on the other side of the doorway to room 6, there was a brick base about 1.30 metres high with a channel in front of it; it would seem to be in relation to the unusually wide doorway of room 7, and similar bases occur in corresponding positions in the courtyard of each of the annexes built by Bur-Sin; it is impossible not to connect these with the decorated bases found in the chapels of the houses of the Larsa age. In the middle of the court, by the drain, there was an oval terra-cotta bath lined with bitumen and bedded to the floor with clay; a similar terra-cotta bath was found in the court of Bur-Sin’s north-west annexe. At some later date in the Third Dynasty, when Dungi’s pavement had suffered from use, it was covered over with a smooth coat of very hard clay about ten centimetres thick; this was photographed by us and then removed.

Most of the doorways opening on to the court retained evidence, in the form of a bitumen mould, of the beam, circular in section, which had formed a raised threshold (being in fact the lower member of the door frame) and of the wooden jambs, while the ashes of the door itself lay thick in the entry; in three cases, rooms 4, 8, 9, there were found among the ashes fragments of gold leaf, chewing that the panels had been overlaid with precious metal. The walls chewed no trace of covering of any kind, and the brickwork had probably been left bare. In the rooms there were often remains of mud plaster, and this was always burnt to a deep red, the colour being so uniform that it was more likely to be due to the burning of wooden panels laid over the plaster than to that of the fallen ceiling. Traces of interior decoration were found. In room 8, near the door, was a crumpled fragment of gold plate cut into open-work patterns, small shield-shape holes, which were filled in with lapis lazuli; similar fragments of inlay, but in banded agate, were found in room 5; in room 9 there were tiny stars of thin gold and sun’s rays of gold and of lapis, apparently from incrustation in wood, together with small gold nails; the decoration of the rooms therefore would seem to have been extremely rich.

The east corner room 3 had in a late period of the occupation been divided into two by a mud-brick partition which perhaps did not rise to the full height of the walls. In the ashes which covered its floor were a number of stone “duck-weights,” most of them split by the heat, and many stone hammers and grinders, some properly shaped, some mere pebbles; several of these shewed traces of gold, and they had clearly been used for hammering up the metal. It might be that this was a room to which offerings were brought and weighed and the gold hammered into convenient form, but it is equally likely that here the Elamites divided their spoil when they looted the building and tore down the gold plating from the walls. That the destruction of the whole building in about 1910 B. c. was due to the Elamites is beyond doubt. A number of tablets were found bearing dates which take us down into the reign of Ibi-Sin, so that the occupation must have lasted until then; the burning of the building and the looting of the tombs beneath it can only have been the work of a foreign enemy in possession of the city; the earliest houses erected over the site were of the Larsa Dynasty, by which time therefore the Third Dynasty structure was ruined and its sanctity gone; the Elamite invasion which brought to an end the reign of Ibi-Sin and the dynasty founded by Ur-Engur is the only historical event which can explain the destruction, and we may see a direct reference to this in the Sumerian lament over the fallen city — “the sacred dynasty have they exiled” —where the poet may be thinking not only of Ibi-Sin carried off into Elam but of the bones of his deified ancestors flung out from their tombs.

Room 4. In the doorway were found fragments of an inscribed alabaster vase of Dungi. In the south-east wall was a doorway leading out of the building into that of Bur-Sin; it was peculiar in having no reveals and might be thought therefore not to have been part of the original plan, but there was no visible sign of alteration and if indeed the door had been cut through the wall the jambs had been re-faced with a very clever imitation of the old brickwork. Close to the door there was in the thickness of the wall a low corbel-vaulted chamber which certainly was original; on the outside it was closed by a mere skin of brick which had been damaged when the wall of Bur-Sin’s annexe was built up against it; on the inside it had been closed by a similar skin only one brick thick, and to mask this, every alternate brick in the corners of the jambs had been chipped back so that the new brickwork might show no break of bond: this is a trick employed several times in the Dungi building. Possibly the chamber had been intended for a foundation-deposit; in any case it had been broken open and looted by the Elamites. When we found it, the entrance had been very roughly blocked up again with mixed bricks projecting beyond the wall face, and inside were two bodies and a number of clay pots of the Larsa period: some Larsa householder digging into the ruins below his foundations must have found the little chamber and had re-used it as a burial vault.

Room 5 was the most interesting in the building. The whole of the north-west end was occupied by a raised brick base divided into three parts, a lower ledge-along the front, a low platform along the north-east wall, and a higher platform in the west corner; the back was destroyed by plunderers who had dug through it into the tomb below, but the front was almost intact. The brickwork was overlaid with bitumen, and sticking to this were found fragments of gold leaf, so that the whole must have been gilded. In the top of the front ledge were six channels running parallel with the front and arranged two deep; starting as shallow despressions they deepened as they ran and then, turning outwards at right angles, came to the edge and were continued as grooves down the front of the platform, emptying into six small brick compartments which formed a row on the floor in front of the platform; in these compartments we found wood ashes [Plate XXXII, 2J. On the top of the lower platform in the north corner there were the remains of one and apparently of two similar channels running down into brick compartments. Along the south-east half of the south-west wall and along the south-east wall was a low bench of brick covered with bitumen in which again there were long channels starting in front of a raised base which faced the door of the room, but these ended not in brick compartments but in cup-like hollows in the top of the bench.

The explanation which suggested itself for the channels and so forth in the west corner was that over each runnel there would be set a porous (or pierced) vase containing scented oil which, escaping from the vase, would run along the channel and trickle down into a fire made in the brick compartment below, and so would go up as incense before a statue placed on the high base behind. This theory is amply supported by a text published by Professor Langdon,1 in which a worshipper describing a sacrifice he has offered says “seven kinds of sweet oil . . . have I burnt upon seven fires.”

Figure 1. The Tomb-shaft of the Dungi Building looking down on to the Stairs. (The steps on the right, leading upwards, are the earth steps made by the workmen for clearing the shaft.)

Image Number: 191695

Figure 2. Paternoster Row, looking along the street to the door of Bazaar Chapel.

Image Number: 191822

Room 6. This was approached from the court by a flight of brick steps, its floor being raised nearly two metres above that of the court. All but one brick of the pavement had disappeared and the room of the superstructure therefore contained nothing of importance. It might however be remarked that the presence of these steps as seen from the courtyard would increase the resemblance of the building to a private house, in which the stairs leading to the upper story are a constant feature and occupy much the same relative position. In room 7 the greater part of the pavement had been destroyed by plunderers digging through into the tomb below, and in consequence nothing of interest survived. The wide doorway is reminiscent of the wide doors of the “reception-rooms” in private houses and must mean that together with room 8 it was specially important (compare rooms 3 and 6 in the south-east and north-west annexes of Bur-Sin respectively); in both jambs of the door there were patches where the normal bitumen mortar had been replaced by white lime cement — the only instance of the use of this material as mortar before the Neo-Babylonian period, and here irregular and inexplicable.

Room 8. Facing the wide doorway were the remains of an altar of the same type as that in room 5; all the back of it had been dug away, but the hole did not go through to any tomb. Every altar of this sort, and there seem to have been eight in the three buildings, has been violated in precisely the same way, and the only explanation is that some votive deposit of intrinsic value was concealed in the brickwork. The Elamites were evidently well informed where to dig for treasure: they have overlooked nothing, and they seem never to have dug where there was nothing to be found. In the north corner of the room is a door to room 10. The fragments of wall decoration found here have already been described.

Room 9. On the pavement of the room, besides the fragments of gold and lapis inlay, there were found a curious stone pick-head and the feet with part of the stand of a piece of sculpture, a standing figure of a bull about one-third life-size, made of copper hammered over a wooden core —the technique with which we are familiar from older (First Dynasty) examples discovered at al Ubaid; there were also fragments of copper vessels.

Room 10 was badly ruined, the whole of its north corner having been rooted out to the foundations; there seems to have been a bench (compare room 5) against the north-west wall. An unusually wide doorway led into room 11, of which the greater part of the pavement had been destroyed by the plunderer’s hole into the tomb beneath. The doorway to room 12, which was at the same high level as room 6, was occupied by a well-preserved flight of brick steps. Room 12 had lost its pavement, and the wall dividing it from room 6 had been so completely destroyed that there was only just enough evidence to prove its existence; whether there was a door through could not be ascertained.

The approach to the tombs lay beneath the high pavement of room 6. The paving-bricks had been pulled away and beneath their level we found mixed nibble, due to plundering excavations which, however, had not gone very deep; just below the crowns of the vaults the rubble gave place to undisturbed and remarkably clean earth which was the original filling. Whereas the foundations of Dung’s building on the north-east were relatively shallow, here the walls went down steadily as the lining of a great pit; in the middle this was open, but at either end it was roofed in by a high and massively-constructed corbel vault; the north-west vault lay under room 12. the southeast vault occupied the south-east end of room 6 itself. In the centre of the pit there was a brick platform which had been originally reached by a flight of steps running through the north-east wall; these led not to the existing floor-level of room 7 but to a threshold about a metre below that level. The approach had been blocked by a wall which was flush with the wall face in room 7 but left a deep recess in room 6. The lower part of the blocking wall was made of thin bricks markedly different from those of the wall proper, but as soon as it rose to the level on the one side of the pavement of room 7 and on the other of that of room 6 the construction changed and every effort was made to mask the existence of the old door. In room 7 the alternate bricks in the corners of the jambs were chipped back so as to give the appearance of a true bond, and the bricks now employed were not the thin ones of the lower section but identical in measure with those in the wall— it is only because they are more cleanly moulded and somewhat better fired that they can be distinguished from the old stock of which they are a deliberate imitation. On the side of the wall facing room 6 no bond could be contrived, but the change in the type of bricks employed comes as soon as floor level is reached. This means that the wall with the doorway through it belongs not to the superstructure as we have it at present, but to an older superstructure standing at a lower level, and that the door was blocked when the wall was incorporated in the present high-level building. Further proof of this occurs in room 7. In the north-west wall there was a doorway through into room 11 the threshold of which was at the same low level as the threshold of the old south-west door, and this door also had been blocked up when the existing pavement was laid, and here too the same effort was made to mask the former opening by the use of special bricks and of apparent bonding into the jamb corners above (but not below) pavement level. This distinction of two stages in the construction and use of the superstructure is most important.

View from inside the Tomb under Room 5 of the Dungi Building, looking up the stairs.

Image Number: 191693

The stairs in the blocked-up doorway led then down on to a brick platform [Plate XXXIII, 1] extending across the whole width of the brick-lined pit underlying room 6; from it, to left and right, there descended further broad flights of steps bordered on either side by a wide brick balustrade with stepped top. The steps running down to the left or south-east passed under the great vault and came to a door in a wall which was a continuation below ground of the dividing wall of the superstructure rooms 5 and 6; the door was closed by a brick screen blocking flush with the wall face, and when this had been removed, the steps were found to continue through the doorway and beyond it into the tomb whose pavement lay 8.60 m. below the level of the superstructure court [Plate XXXIV]. The tomb measured 7.70 m. by 4.15 m., with an internal height of 5.50 m.; the corbelled roof though sagging was almost intact, the small hole at the north-west. end made by the plunderers having done little structural damage. The steps running down from the platform to the north-west passed under the vault (which extended to the north-west outer wall of the building and was therefore longer than the south-east vault) to end in a small square landing; on the right-hand side of this, that is, in the north-east wall of the stair-pit, was a door approached by three steps contrived in the landing and blocked, when we found it, with a brick screen; the steps continued under the screen for the length of the door-passage and led to a brick-paved corbel-vaulted tomb lying under room 11 and measuring 10.70 m. by 4.00 m., with a height of 5.50 m.; the pavement of this and of the south tomb were at the same level. Both the tombs had one point in common; the original floor consisted of five courses of burnt brick set in bitumen and bonded into the walls; over this there had been laid a double layer of burnt bricks set for the most part on edge and with a certain amount of space between them, and above them mud bricks laid partly flat, partly herring-bone fashion, forming a new floor level 1.75 m. above the pavement proper; this floor ran right up to the outer face of the door passage, burying the lower steps, and the blocking of the doorways rested on the mud brick or on a line of burnt bricks which had been set here to act as a retainer for the mud brick; the scattered bones and fragments of clay pots, which were all that the plunderers had left of the furniture of the tombs, lay on the upper floor. The explanation was that Dungi’s architect had been too ambitious and had fashioned his tomb chambers too deep down actually he had penetrated into the Flood deposit —with the result that when the chambers came to be used they were found to be awash with infiltered water, and the only thing that could be done at such short notice was to raise the floor level at the sacrifice of the proportions of the buildings: incidentally, from the fact that the same rough-and-ready measure was employed in both tombs it may fairly be inferred that both were occupied at the same time.

In the brickwork of the walls and vaults there were numerous holes which explained the methods of construction used. Near the top of the wall was a row of holes, long and low, in which had been inserted two beams, side by side, running back as much as two metres into the wall’s core and set in bitumen; these projected twenty or thirty centimetres from the face of the brickwork and acted as brackets. In the outer vaults a horizontal beam was laid along the brackets; in other cases they directly supported long timbers which, sloping inwards and morticed together at the top, formed the framework of the centering. There was no planking behind this, at any rate not in the smaller vaults, but the bricks were laid immediately against the uprights, the line between them being presumably kept by eye; but as the vault rose, intermediate brackets were inserted and the upper part secured by further timbering. The use of two comparatively slender poles to make each bracket was perhaps due to the cost of heavy timber, but it had this advantage, that where the uprights were set directly on the brackets their lower ends could be cut to a broad wedge and fitted between the poles, thus getting a safer lodgment.

The vaults, when we started to unearth them, were in a most dangerous state: not only had plunderers broken through them, but the bitumen mortar had lost its quality and no longer adhered to the bricks, which therefore were quite loose; the sides had sagged and many of the facing-bricks had fallen away and the rest were only supported by the earth which we proposed to remove. Our only course was to shore up the arches with timber. Luckily the holes in the brickwork remained, and by putting in temporary supports and digging down in small sections at a time until the holes were reached, we were able to put in a new centering which not only made the vaults safe but, instead of being an eye-sore, reproduced for the most part the constructional timbering used by the original builders.

All round the stair-pit there were in the brick walls other holes for timber on the level of the top of the central platform; these had no connection with the vaults but seem to have held beams for the support of a wooden gallery which floored over the entire pit, leaving only square openings through which the stairs ran down to the tomb doors. Such a floor can only have been part of the older temporary building, for before the pavement of the existing superstructure-room 6 could be laid, the whole pit was filled with earth. In this underground construction there are a good many features presenting problems which cannot always be solved, but not all can be discussed or even described in a preliminary report. The main facts that seem to emerge are these. The tombs, though designed as part of a plan which was to be completed later, were the raison d’être of the building and were constructed first, together with a superstructure some of which was purely temporary, some was to be incorporated in the later building; judging by existing remains the temporary superstructure may have been confined to the area overlooking the tombs proper: slight changes of line in the brickwork of the pit walls may indicate that even the temporary building was not strictly contemporary with the tomb construction but was added, perhaps after the funeral. In any case the presence of the building suggests that the funerary rites which it served lasted for a considerable time after the actual burial. The two vaults were occupied at the same moment and their doors were walled up, but the staircase to the doors remained open and the presence of the door in the superstructure wall implies that people came down the upper flight of steps to perform ceremonies in front of the doors or on the central platform and on the galleries which prolonged it above the tomb entrances. Then the superstructure as we have it was built, and when it was virtually complete, with its floors at a higher level than those of the temporary building, the doors of the latter were bricked up, the galleries in the stair-pit dismantled and the pit itself filled in and paved over. At this moment a dramatic incident occurred. When we dug away the filling we found that in the upper part of the blocking of the door of each of the tomb chambers there had been made a small breach just large enough for a man to get through; the dislodged bricks were lying in front of the door covered by the clean earth imported for the filling. The tombs had been robbed and, obviously, robbed just as the earth was about to be put in; nobody would have dared to rob them when the pit was still in use, nor, if such sacrilege had been done, would the bricks have been left scattered on the floor and the breach unfilled; the robbers must have chosen their moment when the inviolable earth would at once hide all traces of their crime and they could afford to be careless.

The rulers of the Third Dynasty were deified in their lifetime and worshipped as gods after their death. The tomb then was intended to receive the king’s mortal body, the temporary structure was for the ceremonies of his burial, the permanent building was for the perpetuation of his cult. In this regard the form of it demands notice. It is built not on the lines of a temple (and the temples of the Third Dynasty are known to us by several examples) but on those of a private house; it surely must have been conceived of as the residence of a deity whose human origin could not be forgotten any more than when he was alive on earth his divine character could be overlooked. Death here meant no change of attributes, only a recasting of their relative values, and although the form of service would necessarily be modified the “temple” was in all essentials the palace of the god-king.

The South-east Annexe of Bur-Sin

The building is really a copy, on a smaller scale, of that of Dungi. The walls are much slighter but are relieved with the same shallow buttresses and the doorway in the north-east facade is again flanked by buttresses with T-shaped vertical grooves rising from a projecting base similarly decorated, and the internal arrangments are almost identical.

Through the entrance-lobby 1 one passed into the central court 2, which was brick-paved with a well or drain in the middle made of bricks set in bitumen mortar; against the south-west wall, between the doors of rooms 5 and 6, there was a long low altar with bitumen channels along its top edge and a raised base behind; in the west corner, to the onlooker’s left of the wide door leading to room 7, there was a brick pillar-base corresponding to those in the courts of Dungi and of the north-west Bur-Sin annexe.

Rooms 3 and 4 contained no features of interest. In each a hole had been dug into the pavement by robbers searching for the tomb or tombs below; at the north-east end of room 3 the breach had been effected and the diggers saw that a single vaulted chamber ran below both rooms, whereon the men in room 4 abandoned their task as useless after dislodging only one of the roof-bricks of the vault.

Figure 1. Pillar-base, paneled and whitewashed, from a Chapel (3) in House V, Niche Lane.

Image Number: 191778, 9100

Figure 2. Stoke-hole of Furance in Room 3 of House I-B in Baker’s Square.

Image Number: 191811

Room 5. The pavement was flush with that of the court. Against the south-west wall was a brick altar with the normal channels and raised base, much destroyed by searchers for hidden treasure. Below the pavement was clean earth, the filling of the stair-pit leading to the tombs; the northwest end of this had been disturbed and the tomb door broken through. In room 6 much of the pavement bad been destroyed by plunderers digging through it to the tomb. Room 7 was almost entirely filled by a very large brick altar, very much ruined. The back part of it seems to have served as a raised passage between rooms 8 and 9; the front part was in a series of steps descending from north-east to south-west and ending with a patch of bitumen flush with the pavement, in which were cup-like hollows surrounded by a low bitumen coping; green stains in the hollows showed that round-based copper pots had stood here. Room 8, through which one passed by the side door into Dungi’s building, possessed no features of interest, but the door between it and room 7 was peculiar in that the north-west jamb was hollow and ended in a brick-lined pit going down a metre below floor level. The upper part of the jamb bad been destroyed and the pit cleared out, so that it presumably had contained some votive deposit of value; I cannot quote any parallel for this. From the raised passage at the back of room 7, brick steps led through the north-east door into room 9; here, as in room 10, no objects of interest were found.

The arrangement of the tombs was a reproduction in miniature of that of the Dungi building. Below the pavement of room 5 a steep flight of brick stairs ran down from north-east to south-west; as they started on the inner line of the north-east wall and the stair-well is narrow, there was no space for a proper platform and the bottom step had to serve this purpose — indeed, part of that step had to be cut down to make the top step of the lower northwest flight. On either aide of the central flight, stairways (with no balustrade) ran north-west and south-east to the doors of the tombs; one of these lay under room 6, the other under rooms 4 and 3 half-divided into two by a corbelled arch which supported the party wall between the two rooms of the superstructure. Even the position of the tombs, at right angles to one another and running along the two outer walls of the building, corresponds to that originated by Dungi, but here the mistake of digging too deep has been avoided. In the brickwork of the walls of the stair-pit an offset with a slight change of line coming at a level corresponding to the foundation-courses of the north-east side of the building indicates that work was discontinued at this point to be resumed later; and as the door from the court into room 5 of the superstructure does not agree with the upper flight of stairs but is askew from it the independence of the two constructions, subterranean and above-ground, is proved, so that although no traces survive of a temporary superstructure such as we found in Dungi’s building, we can argue to a similar ceremonial entailing a certain lapse of time between the actual burial and the completion of the “death-house” of the deified king.

The plundering of the tombs had been very thorough, most of the bones even having been removed, but in that under room 6 we found the conical stem of a black-and-white marble chalice bearing a long inscription, a dedication by Ur-Engur to Gilgamish; it was an object rare in itself, but unfortunately threw no light on the ownership of the tomb.

The North-west Annexe of Bur-Sin

The north-west annexe is curiously irregular in ground-plan; it is built round an angle of the old Dungi building and its own outer wall is a succession of arbitrary salients; but internally it preserves that general resemblance to a private house which was so striking in both the other buildings of the group. The outer wall with its shallow buttresses and decorated doorway is true to type; the rounding-off of two of the corners seems to be due to a definite wish to harmonize with the Dungi construction.

The lobby 1 leads to the courtyard 2 which was brick-paved and sloped to a central drain; against the north-east wall was a bitumen-proofed clay bath bedded to the pavement with clay mortar, and in the south corner near the wide door of room 4 there stood a brick pillar-base smoothly plastered with bitumen. Room 3 had at the end farthest from the door a solid brick flight of steps running up against the north-west wall, which was destroyed down to the level of the top step. What happened above, it was impossible to say; there was no landing such as would allow of a return of the stairs along the north-west wall, nor would the ground-level outside allow of a door through the wall; it is possible that this is not really a staircase but a stepped altar or base, but for such a construction we can produce no parallel.

The north-west jamb of the door to room 4 had been destroyed by a Lana tomb which had been hacked down into it, and much of the pavement of this room and of room 5 had been pulled up by the robbers making their way into the vault beneath; in room 4 a few bricks rising above floor level were enough to show that there had been here an altar of the normal type with bitumen channels. Room 6 was largely taken up with another such altar which ran along almost the entire length of the north-west wall; as usual it had been cut into by treasure-seekers; in the doorway the copper shoe of the hinge-pole of the door was found resting on its pivot-stone at the bottom of the hinge-pit. In room 7 there was a large clay store-jar, apparently part of the original furnishing, and here too were found tablets dating to the later years of the reign of Ibi-Sin.

It was in its underground arrangements that this annexe showed the most marked departure from the two other buildings. It contained three tombs, one under rooms 4 and 5, one under room 6, and one under the pavement of the courtyard close to the old Dungi wall; all lay immediately below the surface, their vaults supporting the paving of the superstructure, and the original approach to them had been by shallow pits or by a sloped dromos, not by any such stairway as forms the main feature of the other two pairs of tombs.

Beneath rooms 4 and 5 was a long narrow vaulted chamber, of which three walls were the outer walls of the superstructure but the fourth, the north-east, lay inside the area of the chambers above and had no connnection with the wall dividing room 4 from the court; it was entered by a doorway towards the north-west end of its north-east side which gave on a small pit; the pit had been filled and the door masked by the construction of the wall dividing room 4 from the court, and when the robbers set to work to open the tomb door they had to cut through the foundations of the wall in order to get at it. Similarly the tomb under the courtyard, a small affair measuring only 3.20 m. in length by 2.15 m. in width, had its door at the north-east end, and that under room 6 had its door at the south-west end, both opening on to a common approach-pit; the foundations of the north-east wall of the court passed right across the pit and effectually blocked the entrances of both tombs. Here again then the superstructure was posterior to and independent of the tombs, though the tomb-builder must have had the plan of the superstructure in view.

The existence of the north-west annexe raises the question, why did Bur-Sin require two tomb buildings? and, as a corollary, who was buried in the tombs?

As to the authorship of the buildings there is no doubt at all, for the brick-stamps settle the point; but Dungi might have built a tomb for his father, or prepared his own tomb in his lifetime (in which case the superstructure was added after his death with bricks bearing his stamp), or Bur-Sin might have built it for his father with his father’s bricks: and the same three explanations are possible for the Bur-Sin buildings, but here the matter is complicated by the fact that there are two of them.

We have seen that in the Dungi building and the south-east annexe the two tomb chambers were occupied simultaneously, and bones were found in each chamber; can this mean a continuance in the Third Dynasty of the human sacrifice which marked the funerals of the prehistoric kings? Unfortunately nothing was found in the plundered tombs which threw light on these and other problems; the only thing that seems certain is that we have here the burial-places of kings of the Third Dynasty and the funerary houses in which their cult was celebrated.

Figure 1. Room 11 in House I, Boundary Street. The Chapel Altar with clay bowls in situ, and the two decorated vases.

Image Number: 191803

Figure 2. The Chapel in the School House (Number I in Broud Street), showing the Incense-burner.

Image Numbers: 191825, 40593

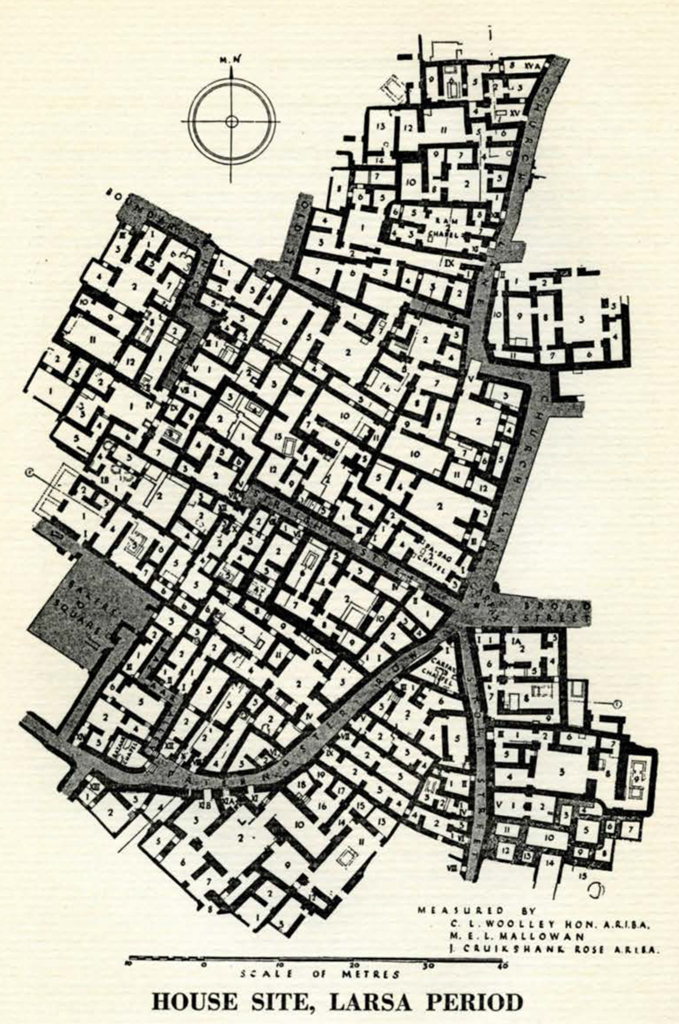

The House Site

The site selected for excavation lies in the south-east quarter of the town area where a long high ridge gave promise of well-preserved ruins. The object in view was to get some idea of the town-planning system employed in any one period, to throw further light upon the character of the private house, and to secure documentary material. Consequently work had to be carried down to such level as seemed likely to give the most complete and consistent results of the sort, and no further; we had to confine ourselves to the first period whose remains were found in tolerable condition. Over the greater part of the site the late ruins were very fragmentary. A few disconnected wall-fragments of the Neo-Babylonian age and others, almost as uninformative, of the Kassite period occurred in the higher levels, but below these we encountered well-built walls standing to a height often of two and three metres. The walls had been constantly re-used, new floors being laid down between them and minor alterations made, so that in themselves they represented a considerable lapse of time; but in nearly ail cases we were able to distinguish one uniform and contemporary level accurately dated by the tablets found on the pavements of the rooms; such documents, which were found in considerable numbers and widely distributed, belonged almost invariably to the Larsa period and generally brought us down into the reign of Rim-Sin. The fact of the tablets being so many and so scattered might imply the destruction of the houses and the breaking-up of business archives; the phase of occupation with which they were associated was marked by the destruction of walls and the burning of woodwork; the obvious inference is that here, as elsewhere on the town site, we have evidence of the looting of the city at the time of its capture by the Babylonian forces after Hammurabi’s defeat of Rim-Sin, in about 1910 B. c. As the ground-plan [Plate XXX] shows, the area excavated by us was a large one, and the buildings on it as cleared were standing in the latter part of the twentieth century B. c. I have already stated that pavements belonging to these buildings were encountered at higher levels than that of the Rim-Sin period, the houses having been repaired after the Babylonian disaster, and it is also true that in very many cases the walls went deeper down and there were lower floor-levels belonging to earlier phases of the same buildings, whose foundation may have gone back to the Third Dynasty of Ur; we sometimes tapped these levels when excavating the tombs of the Larsa age lying beneath the chamber floors. During a long period which lasted well into the First Babylonian Dynasty, the lay-out of this quarter of Ur altered very little; there was constant patching and re-building, as a result of which the levels rose considerably, but the houses were to all intents and purposes the same; in the few cases therefore where no accurate dating evidence was forthcoming for the particular floor or pavement exposed by the excavators, it was none the less safe to assume that the walls gave faithfully the ground-plan of the Larsa house.

It will be seen that at this period town-planning was conspicuous by its absence. The streets are narrow, unpaved, and wind between houses whose irregular frontages depend, clearly, on the accidents of private ownership; building blocks are so large and so crowded that to houses situated in the hearts of them blind alleys are the only means of approach. The dwelling-houses conform to one type more or less according to the possibilities of the site; the central court entered from a lobby and surrounded by the living-rooms, with a stairway going to the upper floor, is the basic idea of buildings of very different sizes and of forms apparently very diverse. Scattered amongst the residences are smaller buildings which can only be shops; the simplest of them consist of two rooms only, a booth-like “show-room” opening on to the street sometimes with a front entirely open, and behind it a long magazine or store; in some cases the back room is divided by cross-walls into two or even three compartments; such are Numbers II, IV and VI Store Street, and V, VII, IX, VIII, X, and XII Paternoster Row and I and II, Bazaar Alley.2 Four buildings, all in prominent positions, are public chapels; two of these are at Carfax corner, one juts out into the little triangular place in Paternoster Row [Plate XXXIII, 2] and one is in Church Lane facing the opening of a aide street which we did not excavate.

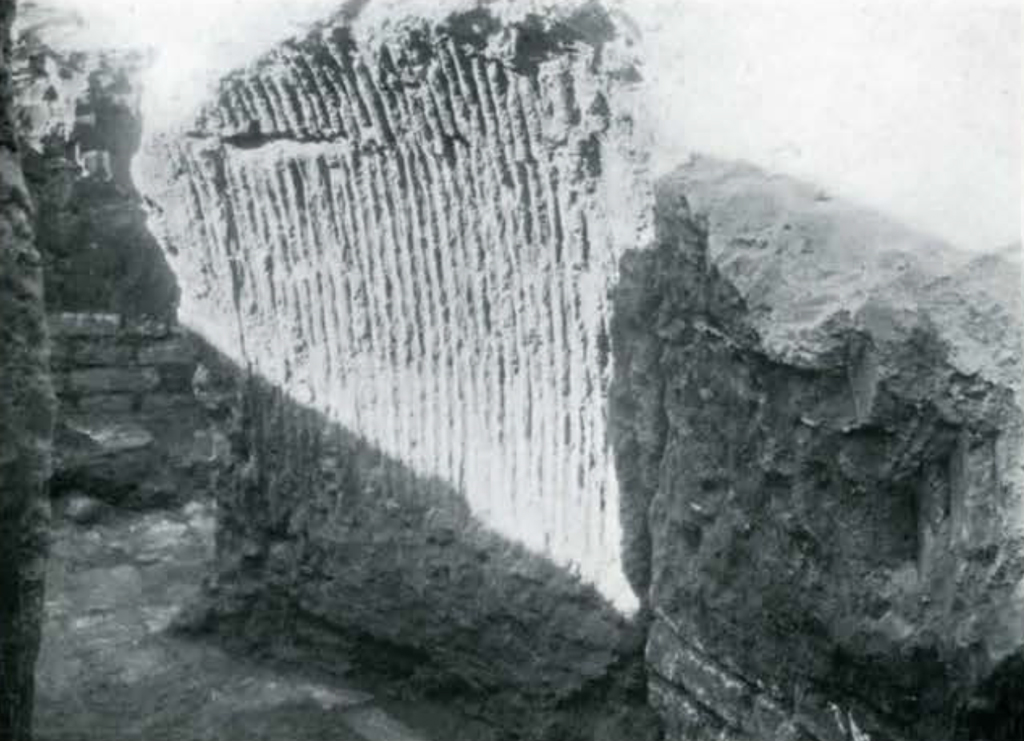

The walls of all the buildings are constructed with burnt bricks below and mud bricks above, the wall face originally plastered and whitewashed so as to disguise the change in material. The proportion of burnt brick varies greatly; in internal walls it may be no more than a damp-course three or four bricks high; a boundary wall, especially one facing on the street, may be of burnt brick to the full height to which it is preserved, that is, to three metres or more. With the constant rise of ground levels, new pavements might be laid against the mud brick, the burnt-brick damp-course being completely buried; but its need was so well recognized that when the same rise in levels tended to make the ground-floor rooms impossibly low and reconstruction was enforced, it was a common practice to raze the walls to the new ground level and rebuild them with a fresh burnt-brick damp-course laid along the top of the old mud brick. Generally the rise of level in the street would he faster than that in the houses, so that a high threshold would be added to the front door to prevent mud and refuse from spreading into the lobby; this is well seen in doors XI, XI-A, XI-B of Paternoster Row, where a flight of steps leads from the street to the low-lying pavement of the entrance-rooms. To anticipate this, when a new internal floor was laid down, it would be put well above street level and the threshold would be stepped up from the outside—only in time to be caught up by the accumulating rubbish of the street.

Figure 1. Pa-Sag Chapel seen from the street.

Figure 2. Pa-Sag Chapel: the Sanctuary Door, showing impression in the earth of the wooden frame and reed panel.

Image Number: 191780

The type of the houses is well illustrated by No. III Straight Street which, though somewhat irregular in ground-plan (it was built up against older buildings in Church Lane) and altered in minor respects by different owners combines most of the features found in other houses. The lobby, here L-shaped, leads into the paved central court 2 which has a drain in the middle and low brick stands, probably for water-jars, against its north-east wall. As the visitor enters, he has on his left two doors of which the farther contains the staircase leading to the upper rooms; the treads in the thickness of the wall and the landing beyond were of solid brick, the return flight was of wood and ran up over the small chamber 3 which, with its paved floor and drain, was a lavatory. Room 4, containing a low brick bench, probably for a bed, and a fireplace, was perhaps a servants’ room, and room 8, with a door leading out into 13, must also have been a service chamber; room 9 (of which the back door was not original) was the kitchen and contained a circular bread-oven and a raised brick cooking hearth as well as an open fireplace. Room 6, entered by a very wide door, was the reception-room; as usual it is long and narrow, closely resembling the reception-room in a modern Arab house, which is long so that runner carpets can be stretched against the wall for the guests to sit on, and wide enough for the mattresses of those who are entertained for the night to be laid across it in a row. The tiny room 5 has a paved floor and drain, and must be a washing-place for the guests; the equally tiny chamber 7, which is scarcely more than a passage to room 10 but has the door from 6 so placed as to leave a deep cupboard-like recess in the left, may have been for the equivalent of the great press in which the Arab stores his guest-room bedding. The upper storey, reached by the stairs and a wooden gallery running round the court 2, extended over these rooms only.

Room 10 is the chapel of the house, with behind it 11, a very small room which in some cases at least served as a library or store-room for the business archives of the proprietor — thus, finds of tablets were made in room 11 of No. II Church Lane, in room 6 of No. XIV Paternoster Row, in room 3 of No. H Bazaar Alley and in room 7 of No. I Broad Street. It is normal for the chapel to be at the back of the house and approached by a door through the guest-room; a difficulty seemed to arise as to its lighting, but this was solved by a discovery in the chapel (room 5) of No. IV Paternoster Row, for in the north-east wall of this, at a height of nearly two metres from the floor, there was found a hole going right through the brick work, a lodgement for a heavy beam, about two and a half metres from the altar end of the room; it was clear that this beam supported the outer end of a pent-house roof which covered in part of the room and left the rest open to the sky; the covered part is the shrine, under the pavement of the open part lies the family burial-vault. This discovery does away with the further difficulty which we had felt as to the sanitary condition of a house which had burials immediately below the pavement of a closed-in room. Against the far wall of the chapel stood a low brick base or altar3 usually plastered with mud and whitewashed; in one instance, room 11 of No. III Boundary Street, we found in situ on the latter the clay platters which had held the food of the offerings. In the wall behind the altar was a square recess, like a hearth, flat-topped, from which there was carried up in the wall a deep groove or open chimney which did not, however, go through the roof as a chimney naturally would, but ended abruptly at what would appear to have been a little below roof level (usually the wall was ruined down below this point, but in room 3 of No. VIII Paternoster Row the wall was of burnt brick throughout and stood to a height of nearly four metres, and the “chimney” ended below this point with the wall-face running flush above it). I should explain the recess as a hearth for burning incense; the open chimney would provide the draught necessary for its burning, and the stopping of the chimney at the top would spread the smoke of the incense over the room instead of letting it escape through the roof.

In the corner of the room, against the altar but distinct from it, was a square pillar-shaped base averaging 1.50 m. to 1.75 m. in height. It was built of brick (generally mud brick, with a burnt-brick base and a flat top of a single course of burnt bricks) and was mud-plastered and whitewashed; the exposed side and front were always decorated with a pattern worked in relief in the mud plaster and though there was differences of detail the pattern was always an imitation of wood panelling. Plate XXXV, 1 shows similar panelled bases in a house in Niche Lane. Such bases can be seen elsewhere, as on Kassite kudurrus or boundary-stones, where they support the emblems of gods, and they also recall the thrones of gods as represented on seals of the Third Dynasty and Larsa periods: we can safely assume that in the chapels they were the stands on which were placed the emblems of the actual statuettes of the household gods.

In most of the chapels, though not in all, we found, immediately in front of the panelled base, let into the pavement but virtually flush with it instead of being buried beneath it, a clay jar or bowl containing the bones of an infant. Occasionally there was more than one such bowl (in a chapel excavated four years ago in another quarter of the town there were over thirty), but one was seldom lacking, and its position as regards the base was identical: it was quite independent of the brick family vault under the pavement of the open part of the room, and where there were subsidiary coffin-burials these always lay fairly deep and not under the roof. Whether this points to a rite of infant sacrifice or simply means that an infant, dying a natural death, might be placed under the special protection of the household god there is no archaeological evidence to show.

Outside the house proper lay the walled area marked in the plan 12 and 13. Originally there had been an independent entrance from Straight Street, but this was walled up, apparently when the door was cut through the house wall of room 9; 12 was certainly an open court; 13 was divided into three by short wall-lengths which left wide gaps or passages between their ends and the face of the house wall; probably the cross-walls supported penthouse roofs, so that there would be a row of three open sheds with an unroofed space along the front of them communicating with the court 12, outhouses of this sort might be attached to any house, compare also rooms 5, 6 and 7 of No. IX Church Lane.

Figure 1. Red-painted clay relief from the door of the Pa-Sag Chapel.

Image Number: 191798

Figure 2. Carved limestone stoup (?) from the Pa-Sag Chapel.

Image Number: 191796

Figure 3. Limestone Statue from the Pa-Sag Chapel.

Image Number: 191791

Notes on Individual Houses

Boundary Street Nos. I and III. These were communicating, and No. III seemed to be a shop, with a brick counter along two of its walls, attached to the dwelling-house. The staircase was unusual, being wholly inside a room 7 and running around three of its sides, with a lavatory recess underneath it. Under room 8 was a brick tomb. The chapel 11 was peculiar in having two panelled bases, one on each side of the altar, and the incense-hearth in the side wall [Plate XXXVI, 1].

In Niche Lane, so called from a curved recess in one of its walls, No. I was a very small but normal house owned apparently by a moneylender; No. III had been confused by frequent alterations and did not seem to be a residence at all; No. V consisted of three rooms of which that at the back was a chapel, and therein resembles No. VIII Paternoster Row and No. X Straight Street; it may have been a shop with chapel attached; the one-roomed places VII and IX should be shops. No. II in the same lane is of the type of the normal private chapel (the original door faced down the lane at the north-east end but was bricked up when the south-east door was made) but does not belong to any house; it may have been owned by someone who had a separate residence, but later it was remodelled and presumably used for a different purpose. No. IV is a sprawling house of the normal courtyard type possessing no features of interest.

No. I Old Street was approached through a narrow alley leading to the usual lobby and courtyard. The house was originally larger than at present, having chambers on all four sides of its court, but the last owner, Ea-nasir, walled off those on the south-east and sold them to the owner of No. VII Church Lane who seems to have been enlarging his premises at the expense of two neighbours. A peculiarity is that the guest-room 5 possesses an altar and tomb beneath the floor and seems to have been used as a second chapel although room 6 was regularly constructed for that purpose.

On the western limits of our excavation there is an open space laid out in part over the razed walls of earlier buildings, which from an oven in the middle of it we called Baker’s Square. In house No. I opening on the square we found a large clay tablet giving the paradigm of the Sumerian verb with the equivalent of its inflections in Babylonian, a very important document, unfortunately isolated. The house was normal except in that the small room 7 behind the chapel 5 had once had a second door giving on the square; this had later been walled up. Probably belonging to the house and approached by a passage behind it was the building I-B which was specially interesting as giving us one of the very few examples of industrial constructions: an original chapel with two small rooms has been demolished and thrown into a single large open court 2 off which opened a stoke-room 3 in whose walls there were three arched stoke-holes [Plate XXXV, 2] serving three circular furnaces in rooms 1 and 4; the purpose of the furnaces is not certain, but since under 2 we found a coffin in which with the corpse there had been deposited miniature copper models of tools which may be those of a smith, and since the furnaces are definitely not bread-ovens, we may assume that they were for smelting copper.

From Carfax there branch out five streets of which Broad Street was too ruined for more than one house in it to be excavated, and of Church Lane nearly the whole of one side had gone leaving only one much ruined house to be planned. In the open space at the cross-roads stood a brick pillar whose use I cannot conjecture.

No. I Broad Street gave us one of our most important discoveries. The house was originally normal in plan with courtyard, surrounding rooms (on three sides) and chapel [Plate XXXVI, 2], the only real difference being that the chapel lay behind the staircase instead of behind the guest-room and that a passage ran between it and the back wall of the house 9. At a later date three of the doorways opening on to the court were walled up, so that from it there was direct access to the lavatory and the guest-room only, while the front door led only to the chapel 8 and by the stairs to the upper storey; a door with descending steps gave direct entrance from the street to the court. This structural change was explained by the tablets of which nearly two thousand were found in the building. Some hundreds of these were of the regular “school exercise” type the flat bun-shaped tablets used for fair copies and so forth; there were very many religious texts perhaps used for dictation or for learning by rote, some historical texts, mathematical tablets, multiplication tables and so forth, as well as a quantity of business records apparently refering to temple affairs. That there was a small school on the premises is obvious; probably the school-master was a priest; the courtyard and guest-room were used as the school, and the alterations were designed to isolate these from the rest of the house, which preserved its private entry while the scholars came straight from the street to their class-room.

No. III Store Street, next door to the school, lay at a higher level but was of old foundation, as tablets found in room 9 were of Third Dynasty date; there was nothing striking about its plan. Next to this again, No. V also lay high up, the threshold of the front door being raised to the full height of the standing wall; only two of its rooms were preserved, but behind them and to the side there was a series of sunken chambers more than two metres deep with heavy walls of mud brick plastered with mud; there was evidence enough to show that these bad been floored over and the walls of a superstructure in burnt brick carried along the top of the mud-brick cellar walls; the sunken chambers are in fact cellars or underground magazines, possibly for grain (a little grain was found adhering to the walls), which would be reached by trap-doors in the floors of the upper rooms. No parallel to this has been found elsewhere on the site, but such underground doorless compartments can scarcely be explained otherwise. Nos. H, IV and VI Store Street were shops of the “lock-up” type. In Paternoster Row, No. III was a private house, curiously irregular thanks to the shape of its building-plot and chiefly remarkable for the preservation of its staircase, of which the beginning of the second flight remained with the corner bricks of its first tread neatly rounded off. Nos. V, VII and IX were probably shops with magazines or work-rooms behind. Beyond these came a very large building having three entrances to the street (XI, XI-A, XI-B), perhaps a khan or inn; judging from the thickness of the walls and the solidity of the staircase in particular it would seem to have been three storeys high. Room 2 is the courtyard, brick-paved like nearly all the rooms, and with a central drain; 3 was also unroofed, and in the plaster of the wall facing the street door there was the impression of the peaked roof of a low wooden shed which resembles and may well have been a dog-kennel. Rooms 5, 6 and 7 might have been stables or store-rooms, the first of them almost entirely dark; 8, which was not fully excavated, promised to be the kitchen; there were found in it large clay boxes divided into compartments which elsewhere occur in kitchens and were probably used for storing the less bulky foodstuffs. Of the stairs, three flights were more or less preserved; the fourth flight, made of wood, turned over room 7 and, through a door above the door of that room, led on to the gallery running round the court. The recess at the bottom of the staircase was utilized for a bread-oven. Room 10 was the reception-room, with a separate entrance from the street through the little triangular room to the north-west. A door (not original) had been cut through the wall into room 16, part of what had been a separate small house composed of a court 16 and three rooms 17, 18, 19 with a door in 19 to the street, now walled up; these may have formed a private suite or the residence of the innkeeper. 14 is a passage leading to 15, the lavatory, and to 11, the chapel, which was also reached from the court by room 9; two side doors in this gave on what was apparently a lane, but at this point our excavations stopped. In the small room 12 behind the chapel altar there were several infant burials in clay bowls. A chapel and two other rooms beyond this belong to a house not fully excavated. No. 13 Paternoster Row also was only partly cleared.

On the other side of Paternoster Row, the first building was too ruined for its character to be made out; it was possibly a shop. No. IV was a large and well-preserved house with two chapels 4 and 5, of which the latter afforded evidence for the pent-house roof over the shrine. From the entrance-lobby a side door led to what seems to have been an annexe of the house proper, a complex of four chambers of which the largest 4 contained bread-ovens; these rooms formed an L enclosing the small corner premises No. VI which certain tools and hammer-stones might identify as a workshop. Nos. VII, X and XII appear to be shops; in the yard 3 behind XII were found many tablets. No. XIV, part of which had been sacrificed for the building of the Bazaar Chapel, also produced a large hoard of tablets all found in room 6 behind the chapel; room 3 was a kitchen almost entirely taken up with stoves and ovens, and as it had a wide window opening on the street it may have served as a confectioner’s shop.

In Straight Street, No. IV was much ruined and had been constantly remodelled. The buildings VI and VIII, each consisting of a range of communicating rooms ending in one entirely filled by a brick burial-vault, are difficult to explain; No. X is rather similar, but as it has a common front door may be an annexe of XII, a small house of normal type; VII is also small but normal.

Most of the houses on Church Lane beyond the Pa-Sag chapel were ill preserved and presented few features of interest. No. V was an old building and much of the existing structure dated to the Third Dynasty; No. VII on the other hand, built at the expense of No. V and of Ea-nazir’s house on Old Street, belongs to the latter part of our period. The entrance is by a long passage which also serves as back entrance to Ea-nazir’s house; the lobby leads into the normal courtyard 2 with service-rooms and a stair of rather unusual form in that the return flight doubled back inside the staircase instead of passing at right angles over a lavatory. The small guest-room 5 and the chapel 6 originally belonged to the house next door; in room 7 was a bitumen-lined pit containing a number of tablets. No. IX Church Lane was also approached by a long private passage having on one side a row of communicating magazines 1-4 while three more 5, 6, 7 seemed to be more nearly associated with the house. The house had lost some of its rooms when the Ram Chapel was fitted up, and its foundations went very deep; the back rooms 5, 6, 7 had all been destroyed below floor level and could only be planned from the underlying walls of the Third Dynasty building; room 8 was the chapel. House No. II on the opposite side of the street had been burnt and most of its walls were razed to the floor; the entrance was through two lobbies into the central court 3; room 5 was the staircase, 8 the reception-room and 9 the chapel; in the narrow room 11 behind this were many tablets which had been stored in clay jars. The further end of the building had been completely destroyed.

Figure 1. Copper Statuette from the Pa-Sag Chapel.

Image Number: 191911

Figure 2. Limestone Statue of Pa-Sag, from the Chapel Sactuary.

Image Number: 191789

Figure 3. Limestone Statue from the Carfax Chapel.

Image Number: 191828

The Public Chapels

There remain to be described the public chapels, of which four examples were discovered in the excavated area. The interest of these buildings, which are quite new to us, is that they illustrate a phase of the religious life and practices of the Sumerians hitherto unknown. The state temples of the great gods are familiar to us, and so now are the chapels in private houses dedicated to the domestic deities; between these come the little wayside shrines, of the lesser gods, excavated this season.

At the corner of Straight Street and Church Lane was the chapel of Pa-Sag, its door opening on Carfax [Plate XXXVII, 1]. Lying beside the north-east door jamb was found a terra-cotta relief 0.61 m. high representing the human-bodied bull-legged demon whose function seems to have been to keep away evil spirits, especially from doors; such are nearly always in pairs, and it is probable that two reliefs of the sort were fixed to the chapel wall flanking the entrance, though of the second no trace was found [Plate XXXVIII, 1]. Three steps in the doorway led up to the raised pavement of the chapel and through a passage with a recess on the right side 1 into the main court 2. On the left there was a small cupboard or compartment which served as a repository for ex-votos; there were various clay pots, two clay models of beds and one of a chariot with the figure of a guardian demon in relief on the back-board, and many stone mace-heads; one of them bore the inscription “the property of Pa-Sag.”

At the back of the courtyard was the sanctuary 4. Immediately in front of its door, facing the entrance of the shrine, was a detached brick altar; against each jamb of the door was a brick base. Between the altar and the left door-jamb lay fallen a square limestone shaft 0.74 m. high and 0.20 m. across, very roughly worked (it had perhaps originally been faced with plaster) having a cup-like hollow in its top and high up on each side a crudely-carved design of birds or human figures; its position suggested that it had fallen from the base by the door [Plate XXXVIII, 2). In the east corner of the court lay, broken in two, a limestone figure of a goddess (height 0 • 51 m.) wearing a long flounced dress and a flat-topped head-dress on which were roughly-incised lines filled in with yellow paint, probably meant to represent a “hair-net” of gold ribbon such as is found on the women of the pre-historic graves; there were traces of black paint on the hair and of red on the flesh, and the eyes were inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli [Plate XXXVIII, 3]. The figure had stood on a wooden base, apparently in the form of a box, for inside it were found a whet-stone and a small copper statuette of the goddess wearing the flounced skirt; the arms had been made separately, and as they had disappeared, leaving no trace, had probably been of wood [Plate XXXIX, 1]. Close to the statue, against the north-east wall, there was the skull of a water-buffalo, remarkably well preserved; it looked as if it had been a trophy hung on the wall.

The door of the sanctuary had reveals on the outside and a bolt-hole in the pavement showed that there had been here an outer door; inside this, between the inner corners of the jambs, was an inner door or screen consisting of a wooden frame filled in with panels of reed which at the moment of destruction had been left standing half-open. The lower part of it, embedded in the fallen mud brickwork of the walls, had left on the soil an impression so distinct that it could be photographed as the original, showing even the grain of the framework and the form of every reed [Plate XXXVII, 2]. Behind this there was a shallow niche in the back wall of the sanctuary in which, on a low whitewashed mud base, there still stood in position the cult statue of Pa-Sag. The statue (0.37 m. high), which was of limestone, originally painted and with inlaid eyes of shell and lapis, represented the goddess standing in a long plain garment reaching to the feet. It had been damaged in antiquity, the lower part of the garment and the feet being destroyed and the body broken in half; the two pieces had been stuck together with bitumen and the figure sunk in the mud of the base with bitumen plastered round it and smoothed off so as to give the effect of a spreading skirt and to disguise the incompleteness of the figure, which was of course rendered unduly squat by the loss of its feet. [Plate XXXIX, 2].

In the corner of the sanctuary there was a very large clay jar, and by it a small collection of inscribed tablets of a business character, apparently connected with the affairs of the shrine, records of service, details concerning landed property, and so forth. Between the sanctuary and the right-hand wall of the building ran a passage giving access to two small rooms, of which one had a door on to Straight Street; these may have been accommodation for the guardian of the little chapel.

The building could hardly have been better preserved than it is; everything is in place or almost in place, and we have a very perfect picture of a type of structure absolutely new to us. The only point that might be called in question is the dedication. Pa-Sag, a little-known deity, has been assumed to be male, whereas the two statues and the little copper statuette found in the chapel are definitely female; actually the texts on which the sex of Pa-Sag is based are not very clear, and further there are cases in the Sumerian pantheon in which the sex of a deity is duplicated or confused; in the present instance it would be impossible to disregard the evidence of the site, even though it were in more direct conflict with other evidence than is the case. The special province of Pa-Sag was the protection of travellers in desert tracks; no ex-voto Could be more appropriate than the stone mace-head; at the present time any Arab going out into the desert will be armed with a cudgel weighted with an identical head of stone or hardened bitumen.

At another corner of Carfax, between Store Street and Paternoster Row, was another chapel, Carfax Chapel (so-called because its original dedication is unknown), which is smaller and simpler in design. The ground-plan is triangular and the door comes in one side towards the apex of the triangle (the building has been remodelled several times and the position of the door altered, but the chapel is described in its last phase, which is probably that of the late Larsa period) leading directly into a little irregular court, also triangular, the base of which has been partitioned off to form two compartments, the sanctuary proper and another room. In the court there was a raised base in the apex of the triangle and another on the right side of the entry door; a rough circular limestone shaft with a cup-hollow in its top was reminiscent of the carved shaft in the Pa-Sag chapel. On the ruins of the thin screenwall of the sanctuary, which had been closed by a door with a timber frame and reed panels, was found the cult statue, a limestone figure of a goddess (height 0.43 m.), seated and wearing a long flounced garment; the eyes were inlaid, and the hair sheaved traces of colour [Plate XXXIX, 3]. Inside the sanctuary was a clay box measuring 0.47 m. by 0.30 m. and 0.17 m. high decorated with figures in relief, snakes and a very rudimentary female figure; somewhat similar clay boxes and lids with the snake ornament have been found elsewhere on the site in strata of Larsa date, but their use has not been known; it is therefore the more interesting to find one in position in a shrine. The snake emblem would seem to connect the goddess with some chthonic cult, but there were no inscriptions to identify her.

A somewhat similar chapel stood farther along Paternoster Row facing down the street at the corner of a little alley which ran through what was apparently a bazaar. A high flight of steps led to a door with ornamental reveals [Plate XXXIII, 2]; the interior was divided into a forecourt and a sanctuary, the latter having the normal statue-niche in its back wall. No objects were found here. Two-thirds of the way up Church Lane there was another building closely resembling the Pa-Sag chapel except for the fact that it was double, a wider court having two sanctuaries at its far end. Steps led up from the road to a small antechamber to the court 2. In this was the free-standing altar in front of the first sanctuary door, against the jamb of which was a brick base; the sanctuary consisted of two chambers (3 and 4) and had no statue-niche in the back. The second sanctuary was also double (rooms 5 and 6) and had no altar in front of its door but had a brick base against the door-jamb. The entire north-east side of the building was destroyed. The only object found here was a very fine head of a ram in dark steatite, made in two pieces (height 0.08 m.); it is the head of a ceremonial staff such as would be set upright on either side of the statue [Plate XL, 2].

Two other objects certainly connected with chapels of this sort were found loose in the soil covering the ruins. One [Plate XL, 1] is a terra-cotta relief 0.73 in. high, resembling that found by the Pa-Sag chapel door, but representing a goddess holding a vase out of which run two springs of water. The other is a fragment 0.17 m. high, the upper part of a clay figure in the round, a seated god with horned crown and long beard wearing a fleece cloak over one shoulder; it is very finely worked and of particular interest in that over the whole surface the paint is fairly well preserved [Plate XL, 3]. Like the limestone statues, these clay figures were all painted. The god had black hair and beard, his crown and some of the beads of his necklace were yellow, the flesh was tinted red and the fleece black and white. The Pa-Sag demon was painted red all over except for the hair and beard, which were black; the goddess relief has lost all traces of paint.

In a preliminary report there is no space to describe the other objects from the town site, mostly found in the graves beneath the house floors or in graves which underlay the vanished houses of higher levels, though some of these, especially the examples of Kassite and Neo-Babylonian glass were very interesting. The tablets too must await further study; here I can only say that we seem to have material enough to identify the owners of most of the houses of the Larsa period and to learn something at least of their activities. These documents, not always of any great interest in themselves, gain immensely in value from their association with individual houses and should furnish a remarkably detailed account of this quarter of the city of Ur.

Figure 1. Terra-Cotta relief of a goddess.

Image Number: 191886

Figure 2. Steatite Ram’s Head from the Ram Chapel.

Museum Object Number: 31-43-173

Image Number: 191801

Figure 3. Fragment of a painted terra-cotta statue of a god.

Image Number: 191828

The Neo-Babylonian Town