IN THE collection of Greek vases made by the late Henry C. Lea, which, through the generosity of his family, has now been presented to the University Museum, are several notable pieces. Of these the earliest is the eye-kylix of Figures 1 and 2, acquired by the Museum early in 1931 by gift of Arthur H. Lea, Esq.

Museum Object Number: 31-19-1

In about 530 B.C. the first red-figured pictures appeared on Greek vases and at once began to supplant paintings done in the older black-figured style. No class of vases reflects more clearly the conflict of the two techniques than the eye-kylikes, cups with a small round picture in the interior, and on the exterior two pairs of apotropaic eyes. Some of these cups are decorated entirely in the older black-figured fashion; on others artists have combined the two techniques, painting a black-figured picture on the inside, and red-figured eyes on the outside.1

Museum Object Number: 39-19-1

Image Number: 2816

At the same time that this change in technique was being effected, came a change in the character and disposition of the design. Artists were no longer satisfied to paint merely a gorgoneion or a cock in the interior field, or willing to relinquish the entire exterior field to eyes, stylized noses, and palmettes. Instead human figures were used for the interior picture and on the exterior also men made their appearance between the eyes or adjacent to handles. For these figures of the exterior a mixed technique was sometimes used, the obverse, for example, being black-figured, and the reverse red-figured.

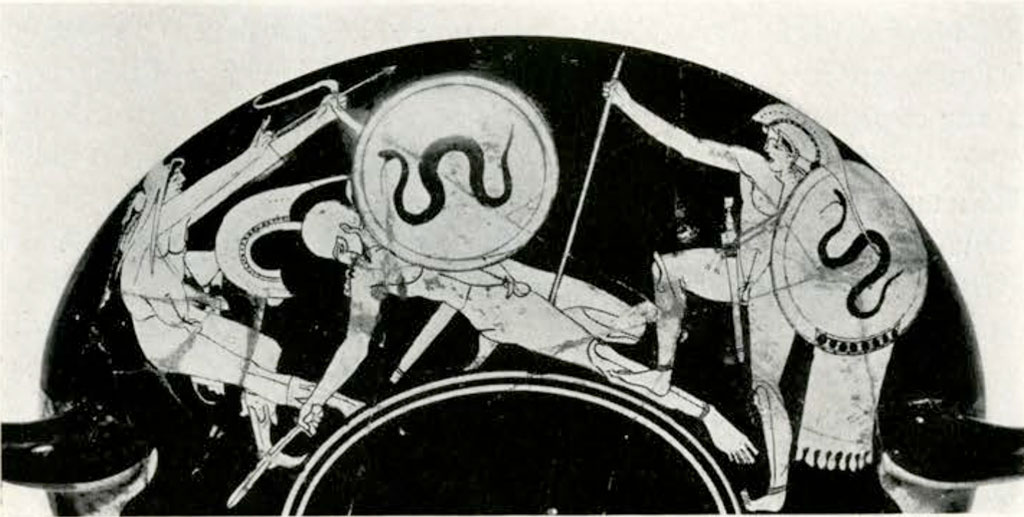

Most eye-cups which show a human being on the interior show some kind of figure, if not men at least sphinxes or a pegasus or a plant on one or more faces of the exterior. Exceptions are the cup in the Ricketts-Shannon collection, signed by Hischylos as maker [Figure 3],2 Villa Giulia 18587,3 and our cup. The pictures inside these cups are black-figured. On the outside are red-figured eyes, with the usual stylized nose and eyebrows, and, adjacent to the handles, palmettes.

Image Number: 2841

The shape is very like the second type of red-figured kylix given by Caskey in his Geometry of Greek Vases, page 177. The handles are placed half way between the rim and the reserved line below the exterior decoration. A moulding, bordered above and below by reserved lines, defines the division between stern and bowl. The lower surface of the foot is reserved and flat, but there is a broad band of black glaze within the stern. The clay is ruddy in color; the black glaze of the best. Relief lines, the double strokes of which [Figure 4] are plainly discernible, are used for the contours of the red-figured exterior decoration and even for the margins of the reserved red above the handles. Between the eyebrows are reserved dots. On both faces of the exterior the painter has corrected the noses by making them smaller.4 The nose on one face only is embellished with lines of dilute wash. The centers of the eyes are red dots, the circles outside the bull’s eye, separated by incised lines, are red, white, and black, respectively. The leaves of the palmettes are not separated; their cores are reserved.

The attitude of the warrior of the interior picture is closely analogous to that of the snake-slayer of Figure 3; in both cases the shield is held ready on the left arm, and the drawn sword on the right is aimed at a pursuing foe, but in our picture no snake rears his head to explain the warrior’s attitude. Our picture, moreover, is done more carelessly. Details like the knotted ends of the chlamys, the bent fingers inside the shield, the lines which indicate the borders of the greaves, become clearer on comparison with the similar details of the Ricketts-Shannon cup.

The foot of our warrior recalls the drawing of the Delos painter,5 but the resemblance is not sufficient to attribute the vase to this artist.

Image Number: 2814

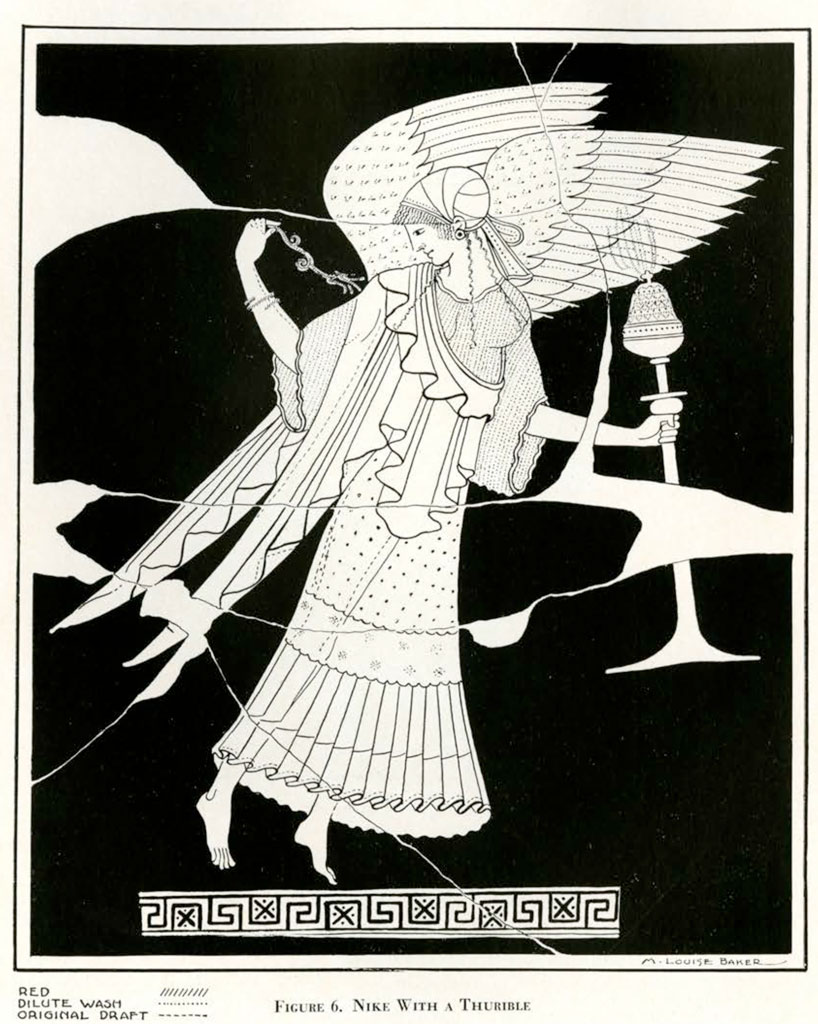

A second vase [Figures 5 to 7] from the collection of the late Henry C. Lea was also acquired in 1931 through the generosity of Arthur H. Lea, Esq. The shape is a modified form of the officially inscribed black-figured amphoras which were given as prizes in the Panathenaic games. The egg-shaped body tapers to a small base, the curved profile of which corresponds to that of the neck. A moulded band separates the neck from the shoulder. Patterned ornament is reduced to a minimum: a band of stopped maiander alternating with saltire-squares beneath each picture. On the obverse is a flying Nike, in her right hand a flower, in her left a lighted thurible. On the reverse is a youthful athlete wrapped in a himation and carrying a staff.

Museum Object Number: 31-36-11

Image Numbers: 2963-2967

The vase is not free from restorations. It has been broken and the seams between the fragments, widened first by corrosion and then by filing, are filled with plaster. Several small portions are missing. When the vase was acquired, the entire reverse surface was painted black; the reserved picture had been damaged and perhaps the greenish-yellow tinge of the adjacent dark glaze did not meet the dealer’s requirements for color. On the obverse, the restored parts are luckily few. One crack traverses the pointed ends of the himation, a second intersects the body near the waist, and a third crosses the wings. The right hand is defaced.

Over her chiton of sheer, crinkly material the Nike wears a close-fitting garment of heavier stuff, which is finished below with a broad border on which the dots are combined with crosses.6 About her head is tied a kerchief, beneath which short locks escape over the forehead and longer tresses on the neck. She wears earrings indicated by a dot and circle. The iris of the eye is represented by a dot set well toward the nose; the eyelids are separated at either end. The thurible is of metal.7

The figure resembles closely the work of the Berlin painter whose style, thanks to the genius of Mr. Beazley, is now so well understood.8 Compare the face, the ear, the earring with those on the fragment of Athena in Bryn Mawr9 or the face and general pose of our figure with those of Ganymede on the Louvre Krater.10 If further confirmation is needed, there are the lines which edge the neck and sleeves of the chiton; those marking its lower margin; the drawing of the beautiful feet, especially the ankle bones and the long thin toes; the sparing use of the relief line for contours; the alternating attachments of the saltire squares.

Museum Object Number: 31-36-11

Image Number: 209872

All of the amphoras of Panathenaic shape are placed early in the long career of this artist, whose earliest pieces antedate the beginning of the fifth century and whose latest reach to 460 B.C. Perhaps our vase should be regarded as one of the earliest of the amphoras of Panathenaic shape. The wings and feet, curiously enough, are headed in opposite directions, and the band of patterned ornament is applied without regard to the central axis of the face of the vase.

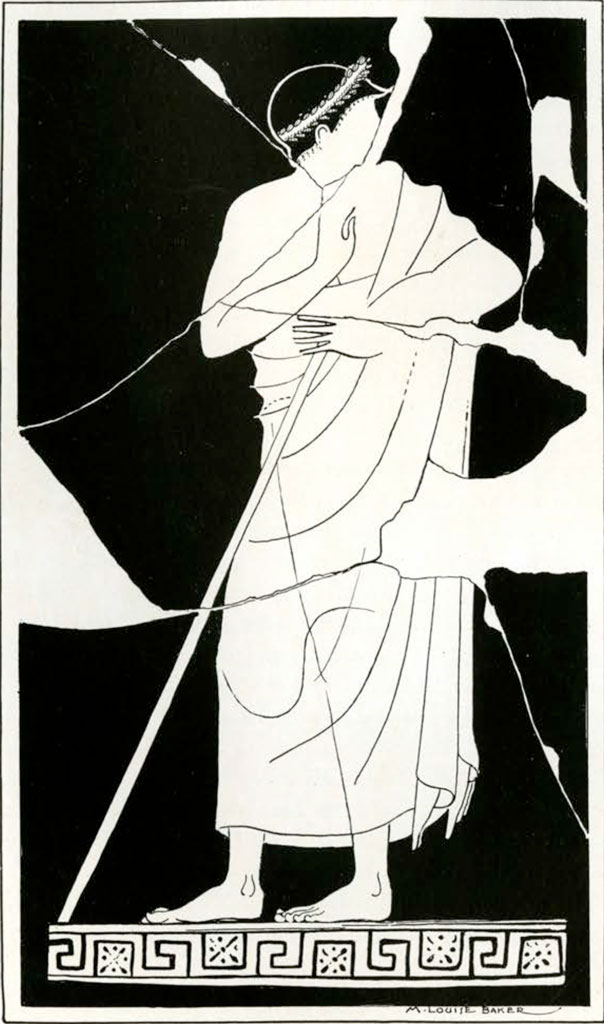

The sadly damaged figure of the athlete on the reverse [Figure 7] doubtless represents the boy to whom Nike is flying with her gifts, just as on the Boulogne amphora, Eros on the obverse is flying toward the boy of the reverse picture.

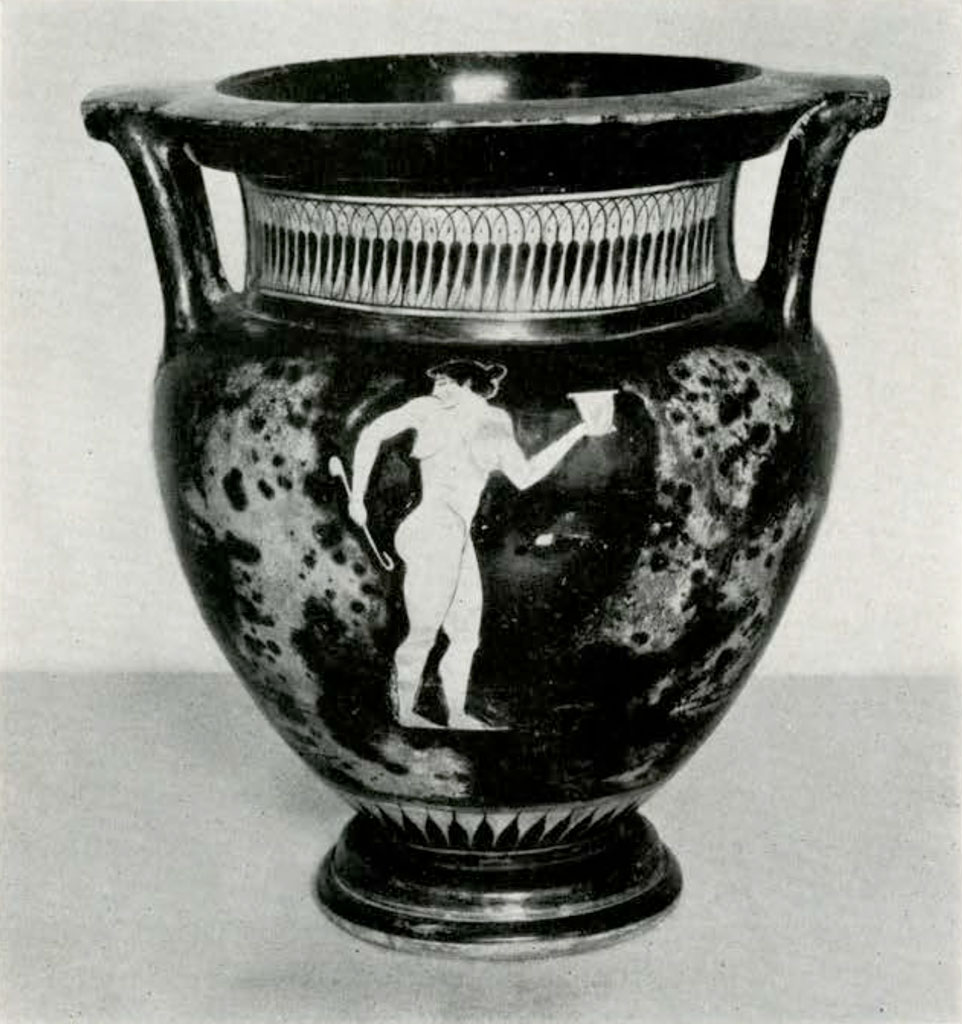

A third vase [Figures 8 and 9] from the Henry C. Lea collection which was presented to the Museum ten years ago by the late Nina C. Lea has not as yet received the attention that it deserves, not, at least, of late years or in this country. In the German Institute in Rome, however, so Mr. Beazley has kindly informed me, there exists a drawing of the vase, bearing the legend: ‘scoperto a Poggio Gaiella presso Chiusi inviato da D. Luigi Dei con lett. d.d. 10 Giugno 1841.’ Like other vases of the Lea collection, it was purchased in America many years ago. It has been mended but no parts are missing.

Museum Object Number: 31-36-11

On the obverse a naked girl, cup in one hand, ladle in the other, looks back over her shoulder at the ardent boy of the reverse who hurries to the delights of the banquet with a garlanded wine jar in his hands. Around the neck of the girl is a necklace on which is strung a bead or amulet, and about her right thigh is strung another bead. Relief lines are used for the few interior markings and for the entire contour of the girl except for hair and nipples which are reserved. Necklace, thigh-band, and the iris of the eye, thus indicated to be blue, are rendered in dilute wash. The boy on the reverse wears a garland painted red. The outer margin of his hair is reserved; short locks on neck and forehead are indicated by rows of dots. Relief lines in this figure are used for interior markings and for the contours of face, neck, and that part of the shoulder which is so close to the neck as to make the use of a brush difficult. The rest of the contour is outlined with the brush.

Where this preliminary brush work underlies the coat of black glaze applied to the body of the vase, the glaze is well preserved, but in other areas, particularly on the obverse, the glaze has cracked and gone, leaving in some cases patches of red color, which plainly underlie the black glaze. Miss Richter11 has explained such patches as remnants of the μίλτο which was applied to the clay in a leather-hard state before the glaze was put on. Dr. Zahn on his visit to the Museum explained this red color in a different way: ‘Whenever the glaze of Greek vases did not get in the oven sufficient air to become thoroughly oxidized, when for example vases touched one another in the kiln, the glaze turned out red instead of black. In the case of this vase the first application of glaze was deemed unsatisfactory and a second was applied.’

Museum Object Number: MS5688

Image Number: 2929

A column-krater with a single figure on both obverse and reverse is sufficient in itself to suggest Myson. The massive shoulders, rather artificially raised, the prominent underlips and chin,12 the red garland, the curves of the ears and the small dots to represent curls about the margin of the hair, indicate Myson as the artist of our vase. Mr. Beazley has kindly confirmed this attribution and adds that Myson is here ‘getting like the Pig painter who continues the style of Myson, and might even be Myson in his later years.’

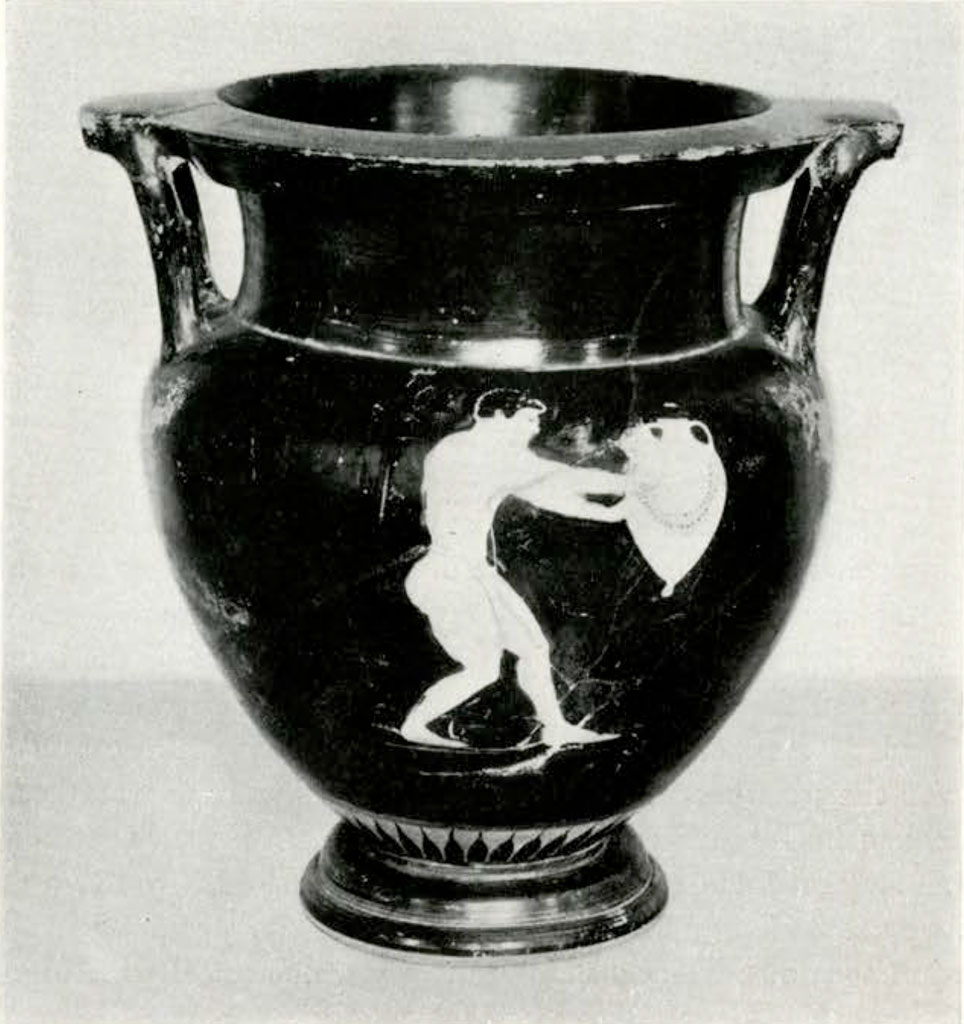

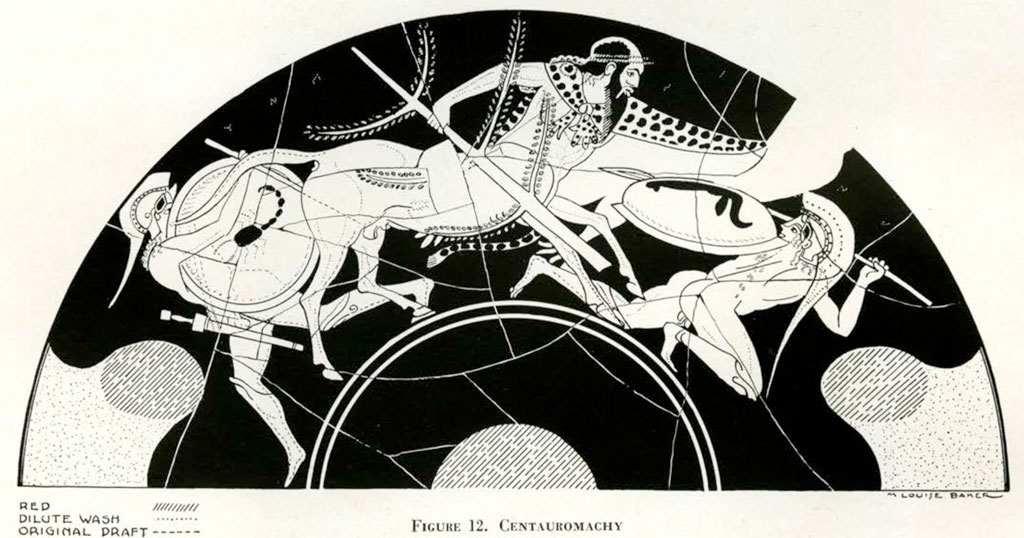

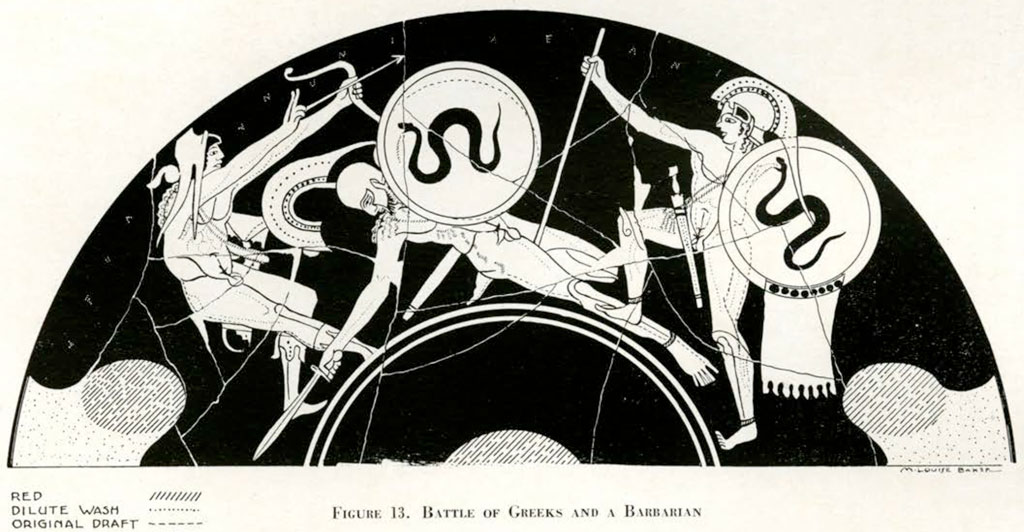

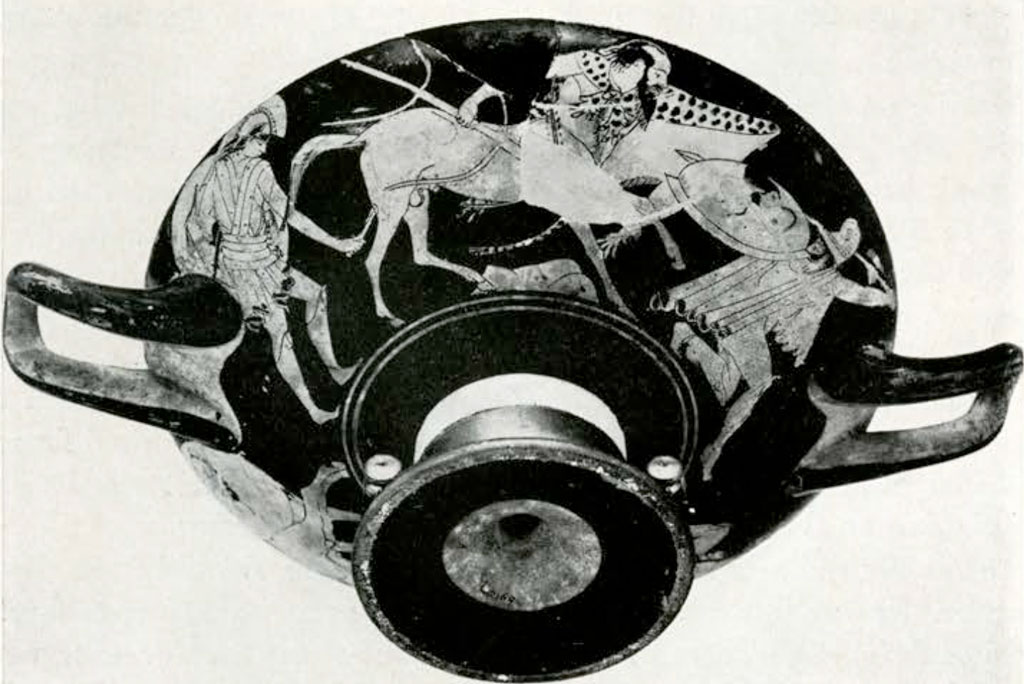

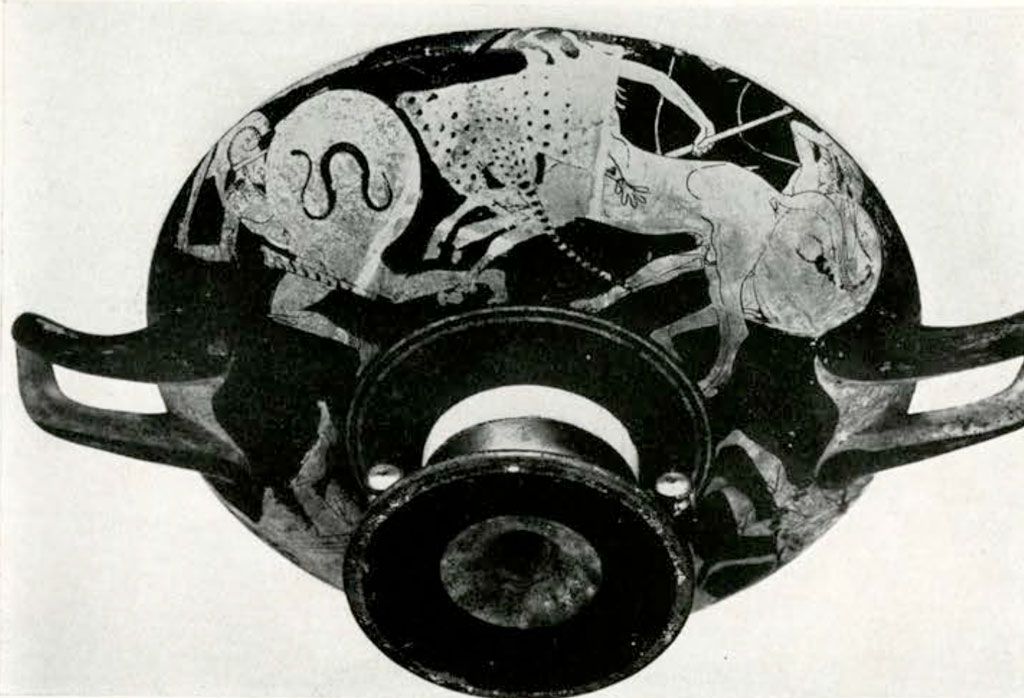

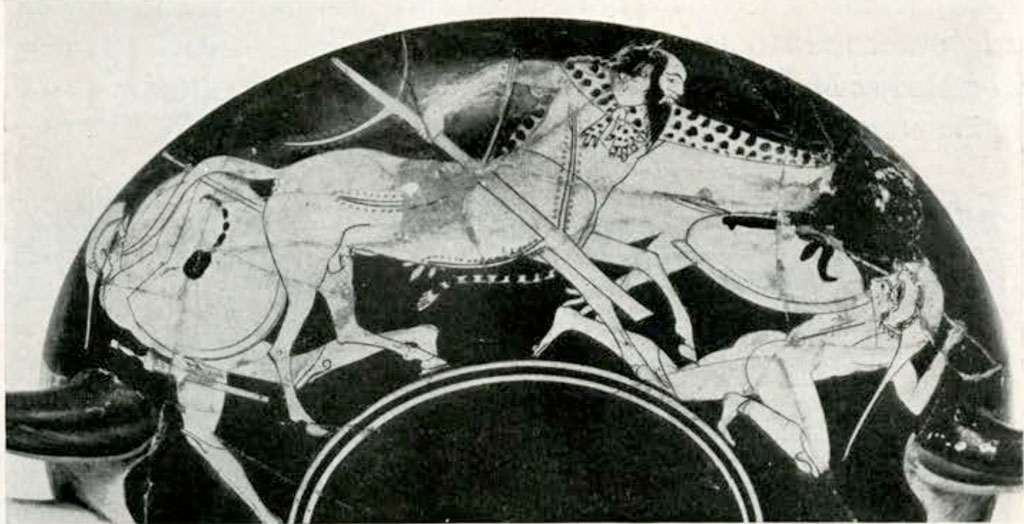

A fourth vase from the Lea collection [Figures 10 to 13] presented to the Museum early in 1931 by Arthur H. Lea, Esq., constitutes an important acquisition to our collection of Greek vases. If compared with the Lea eye-cup [Figure 1] it will be seen that it is considerably smaller; that the transition from stem to bowl is effected with greater subtlety; that the base of the foot is no longer flat but sloping and broken by a moulding. The form, in fine, is the perfected type of kylix used in the best period of Greek ceramic art. The two pictures on the exterior of the cup [Figures 12 and 13] show a masterly portrayal of the favorite themes of Greek sculptors. On either side a battle rages; on the one a centauromachy, on the other a battle of two Greeks against a barbarian, contests the one against inhuman, the other against human foes.

Museum Object Number: MS5688

Image Number: 2932

But first let us look at the entirely unrelated picture of the interior.13 It is larger than the corresponding picture in the eye-cup and is encircled by a band of stopped maiander. As on the Myson krater, a boy is ready for the pleasures of the banquet. The krater is wreathed; with an oinochoe he fills his cup, but someone calls. He turns to look and the wine streams from his jug. The cup in his hand is not like the one which we are studying; its base is flat and its stem straight and slender. At the juncture of bowl and stem are two protuberances which look like rivets. Probably the cup was of metal. Within the circle of maiander is a meaningless inscription.

Exceptionally clear traces of the technical processes employed by our painter may be seen in Figure 11. Before the cup was fired, when the clay was leather-hard, the outlines of the figures were laid out with a blunt engraving tool. The relief lines which outline the entire picture except the reserved contour of the crown of the boy’s head, followed the grooves made by this instrument, and the first brush strokes in black glaze further concealed them. The grooves remain visible only where details like the hand or the cup were superimposed upon the first sketch, or where the first sketch was altered. Thus portions of the course of this tool may be seen where the lines of the abdomen cross the field of the kylix, and where that of the buttock crosses the line of the left hand. Alterations of the first sketch may be seen along the calf of the boy’s left leg, the left shoulder, and the upper contour of the jug. The inner contour of the boy’s left thigh was twice corrected, and as to the lower margin of the jug, it seems that the artist played idly with his tool, until he arrived at the curve which suited him. That the course of the interior relief lines was also traced with the engraving tool is shown by the grooves across the field of the kylix, where it breaks the frontal relief line. A scrutiny of the boy’s left calf shows that there was a preliminary sketch for some, at least, of the interior markings in dilute wash. On the shoulder of the krater appears a part of a discarded preliminary sketch which I cannot make out.

Museum Object Number: 31-19-2

Let us call the face of the vase with the centauromachy [Figure 12] the obverse. The figure of the centaur is boldly laid on across the center of the field. His only defensive armor is a leopard’s skin tied about his shoulders and held extended on his left arm like a shield; his only weapon a tree broken from his forest home. This monstrous bludgeon has already bruised and torn the back of the warrior on the right, but he is far from being hors de combat. His lithe and agile body, protected only by helmet, shield, and greaves is clear of the centaur’s front hoofs and his spear is aimed straight past the leopard’s skin at the centaur’s heart. His comrade on the left, however, takes no chances; holding his shield before him as protection if the rear hoofs should fly up, or the tail give a wicked swish, he peeks over its edge, and plunges in his spear between the hindquarters of the beast.

Museum Object Number: 31-19-2

The composition is arranged with great skill. The right foot of the warrior on the left is extended to fill the empty space beneath the handle and almost meets the foot of the right warrior on the reverse [Figure 13]. Similarly his other foot is extended to meet the left foot of the warrior on the right. The space above the centaur’s back is admirably filled by the tree and by the centaur’s right arm. The torsion of the outer figures adds to the unity and compactness of the picture.

Alterations of the preliminary sketch are notable on the extended leg of the warrior on the left, which was originally drawn smaller; and on the right foreleg of the centaur. The grooved line of the preliminary sketch for the right contour of the warrior on the left may be traced across the field of his shield; that of his spear across the centaur’s flank; that of the baldrick across the shield, the warrior’s right arm and the centaur’s tail. The curved line on the hindquarter of the centaur was outlined with the engraving tool before being painted in dilute wash. Red is used for the leaves of the centaur’s tree, for the double fillet about his head, for the blood that gushes from the wound of the right warrior, for the part of the baldrick that shows at the extreme left of the picture. Relief lines outline the entire picture except the long locks on the neck of the centaur.

Like his contemporaries, the artist is interested in foreshortened surfaces. The curved rim of the shield of the warrior on the right is indicated by shading, but the blazon—a bull’s head—is cut in half according to the old black-figured tradition of rendering in perspective the picture on a shield.

Museum Object Number: 31-19-2

Museum Object Number: 31-19-2

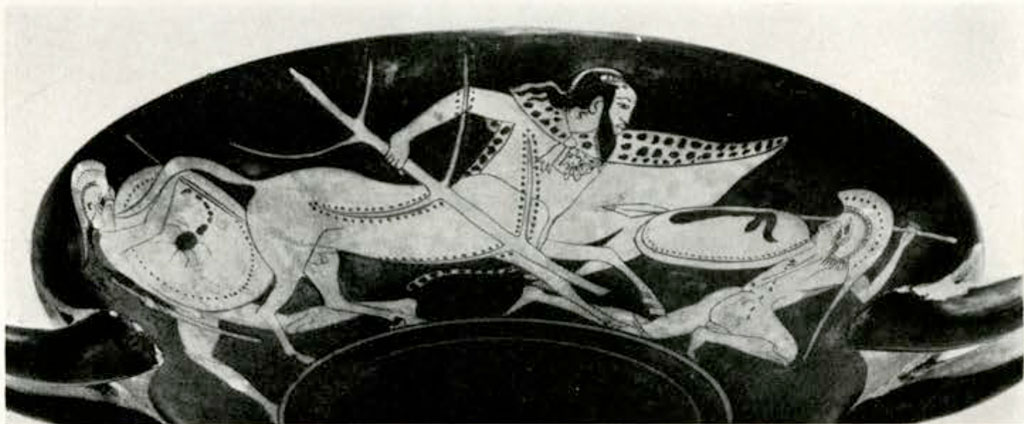

On the reverse, the center of the picture is occupied by a dying warrior. Blood gushes from his wound; his eyes are already unseeing, but he holds his shield high, for how else could the central space of the picture be filled? The curved figure of the bowman serves admirably to bound the picture on the left; the straight lines of arms and arrow lead the eye over the curved surface of the cup toward the boy on the right. The archer wears a barbarian cap and high boots. His skill as a bowman is suggested by the torsion of his figure, as if the artist would tell us ‘this archer can aim straight from any position.’ The two raised fingers of his right hand further bespeak his effortless skill. The guileless boy rushing up on the right is no match for such an adversary.

Originally the artist intended to foreshorten the shield of the dying warrior. Incised lines for an elliptical contour may he seen crossing the field of the shield. These lines like the circles of the final drawing were incised evenly and cleanly with compasses. In the figure of the bowman, alterations may be seen of the line of the buttock, of the course of the relief line which marks the upper contour of the abdominal region, of the right thigh, of the flap of the quiver. The original sketch for the right contour of the figure of the boy on the right may be traced in the field of the shield. The inscriptions on both obverse and reverse are meaningless.

The identification of the painter of this cup I owe to Mr. Beazley. It is by the Foundry painter.14

Unmistakable resemblances to the figures on the other vases in the list may be seen on our cup. Compare, for example, the head of our centaur with that of the vomiting banqueter on the Lecuyer cup in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge15; or the interior markings of the abdominal muscles of the bowman with those of the wrestlers on the London cup16; or the rectangular toes of the right foot of the dying warrior with those of the votive foot on the Berlin foundry vase17 or of the left foot of the banqueter just cited; or the shading and blazons of the shield and the shield-apron on our cup with those on the Harvard and Brussels cups.

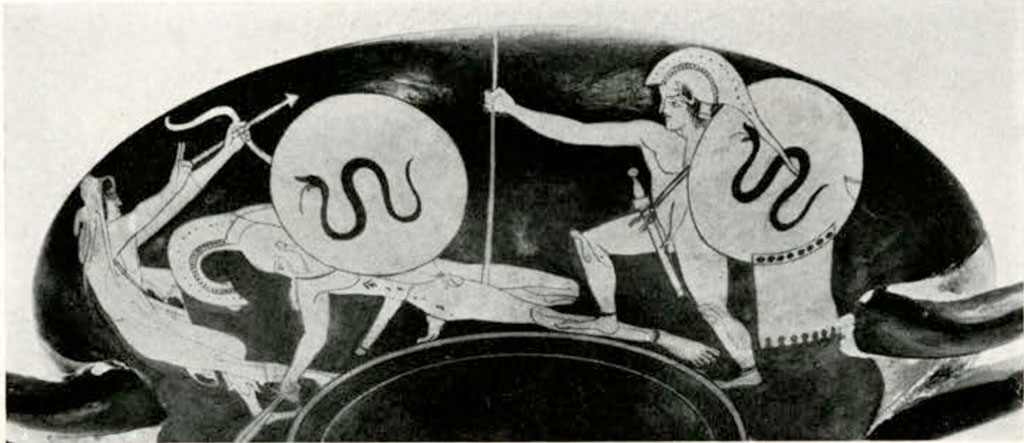

The addition of the Lea cup to the list of works by the Foundry painter involves another addition also. Mr. Beazley points out to me that its sister-cup is Munich 2614,18 which, by kind permission of Dr. Sieveking of Munich, is reproduced in Figures 14 and 15. The resemblance of the centaur of Figure 14 to our centaur and the similar arrangement of both obverse and reverse is apparent. The posture of the boy on the interior is very like that of the fluting girl on the Lecuyer cup19; and the strange blazon on the shield of the interior is exactly paralleled as Mr. Caskey has observed20 by that on the Boston cup with arming scenes.

Two other vases which Mr. Beazley thinks will be added with the Lea cup to the list of works of the Foundry painter are the Munich cup 264021 and Villa Giulia 50559.22

Museum Object Number: 31-19-2

Pictures of battles were not hitherto included in the works of the Foundry painter, unless the wild wrestling match on the London cup be called a battle. The pictures on our cup—far more than those of its sister-cup in Munich—show that the artist in his most inspired moods could convey the stress and strain of battle as well as the delights of the banquet. Brygos would perhaps have done it better. His silene on the fragments in Castle Ashby23 is more of a beast than is our centaur; his figures are more vibrant. But the boldness and beauty of the drawing on our cup proclaim the Foundry painter a great artist, a worthy contemporary not only of Brygos but of the sculptors who carved the Aeginetan pediments in 490-480 B. C.

One word about the history of the Lea cup. It was purchased, as nearly as Mr. Arthur H. Lea can ascertain, in the eighties. In 1896 the Metropolitan Museum purchased a kylix with similar paintings, which was long on exhibition but is now relegated to the case of forgeries in the study-room. Mr. Hugh Jacobs, on his recent visit to America, called my attention to the fact that the pictures on this forged vase [Figures 17 and 19] copy exactly those on the Lea cup.

Museum Object Number: 31-19-2

1 For a partial list of such cups, see Walters, J.H.S., 29, p. 110. ↪

2 I am indebted to the Society For the Promotion of Hellenic Studies for permission to reproduce this vase from volume XXIX, plate VIII of their Journal. ↪

3 C.V., Villa Giulia, III, H e, pl. 45, 1, 4, and 5. ↪

4 Cf. Beazley, J. D., Papers of the British School in Rome, XI, p. 14. ↪

5 Op. cit., p. 15. ↪

6 Cf. the garment worn by Athena on the Andokides amphora in Munich. F. & R., p1. 4a. ↪

7 On thymiateria see Wigand, Bonner Jahrbücher, pp. 46-49, pls. 1-6. The thurible on our vase is type No. 76 on pl. 3. ↪

8 See Bilder Griechischer Vasen, herausgegeben von J.D. Beazley and Paul Jacobstal,II; Beazley, J.D., Der Berliner Maler, where a complete bibliography of the author’s earlier studies of this master is given. Mr. Beazley has recently kindly confirmed the attribution of the Lea amphora to the Berlin Painter. ↪

9 Beazley, op. cit., p. 16, pl. XII, 5. ↪

10 Ibid.. n. 18. pl. 20. ↪

11 The Craft of Athenian Pottery, pp. 53.59. ↪

12 Compare the boys on the column-kraters in Cracow and New York; Beazley, Greek Vases in Poland. pl. 7, 1 and 2. ↪

13 Cf. Bicknell, C.D., J.H.S., 41, pp. 225-230. ↪

14 A list of vases from the hand of this artist—eleven cups and a skyphos—is given in Beasley, J. D., Attische Vasenmulerei des rotfigurigen Stils, pp. 186 and M. Only three of this list are in America, one in the Fogg Art Museum, unpublished; two in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, lately published in ideal fashion by Mr. L. D. Caskey (Attic Vase Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, pls. XI and XII, pp. 26-24). The Brussels cup, ninth its Mr. Beazley’s list, h now illustrated in C. V., Cinquantenaire III, 1 c. p1. 3, 1. ↪

15 Bicknell, loc. cit., pl. XV. ↪

16 Gardiner, E. N., J. H. S., 26, pl. XIII. ↪

17 F.R., Vasenmalerei, p1. 135. ↪

18 F.R., ii, pp. 133.135. ↪

19 Bicknell, loc. cit., pl. XVI. ↪

20 Op. cit., p. 27. The blazon is here called a `nondescript dot’ and compared to the blazon on the Harvard kylix. This we have seen to be a bull’s head cut in half. Perhaps the ‘non-descript dots’ are halves of gorgoneia. ↪

21 F.R., p1. 86. ↪

22 Hartwig, Meister-Schalen, p1. 54. ↪

23 Papers of the British School at Rome, XI, 1929, p1. X, 4. ↪