THE fourth century A.D. marks a turning-point in the history of the Mediterranean World. Permanent war against invading barbarians, inner civil struggles, social unrest and subsequent economic decline during the third century had brought the powerful Roman Empire near the abyss. But it was saved once more. The energetic Diocletian created a new political order and after a brief renewal of the struggle, Constantine, called the Great, consolidated the Empire for a new period of its history. He shifted the capital from Rome to the East, to Constantinople, leaving the West to the future task of building up the mediaeval world by civilizing the intruding Germans, whilst the later Byzantine Empire in the East formed a barrier which saved Europe from being overwhelmed by Asiatic invasions and preserved the seeds of ancient civilization with which to sow later the soil of Eastern Europe, as well as that of the West. The new Empire needed a new mind, for new civilizations are born of new ideas. The classical conception of the world as a harmony in which man, endowed with free will, humanized himself in conformity with universal laws, had completed the cycle of its historical life, incapable to prevent mankind from being extinguished in the struggle which everywhere prevailed. But, already, a new idea had arisen, giving the world a new order. The call was no more for freedom, but for authority; man was no more the center of the world but a tiny mote before an overwhelming Supreme Being, and his aim was to save his soul from his innate sinful nature into a transcendental world. Christianity, first a despised sect, grew stronger and stronger until, purified by persecutions, it formed a community comprehending the soundest forces for constructing a new culture, so that it became the backbone of the new Empire.

Museo delle Terme, Rome

Image Number: 3288

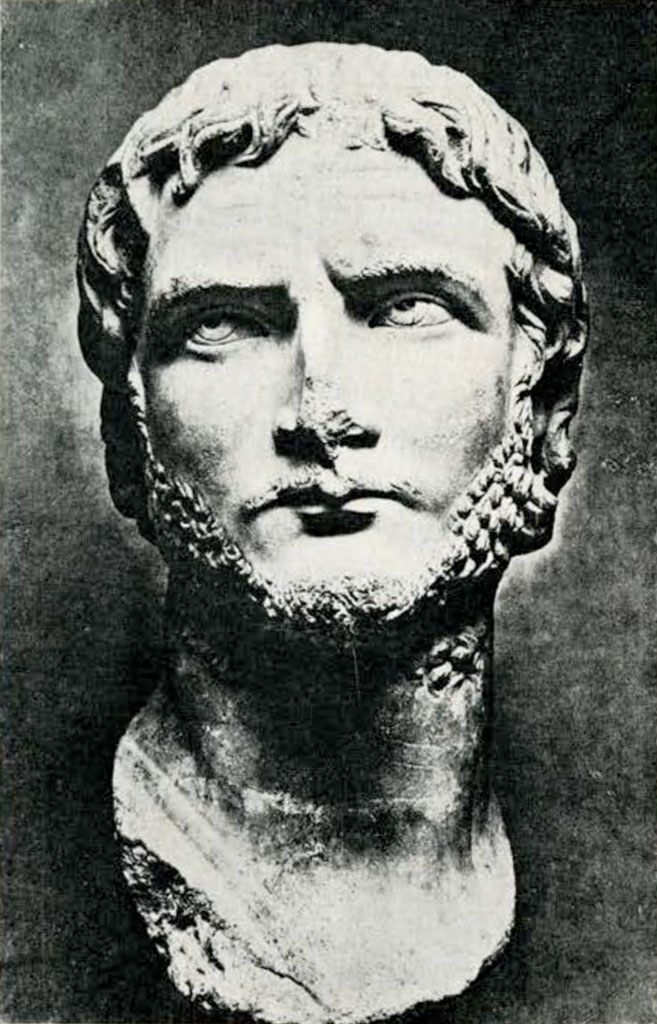

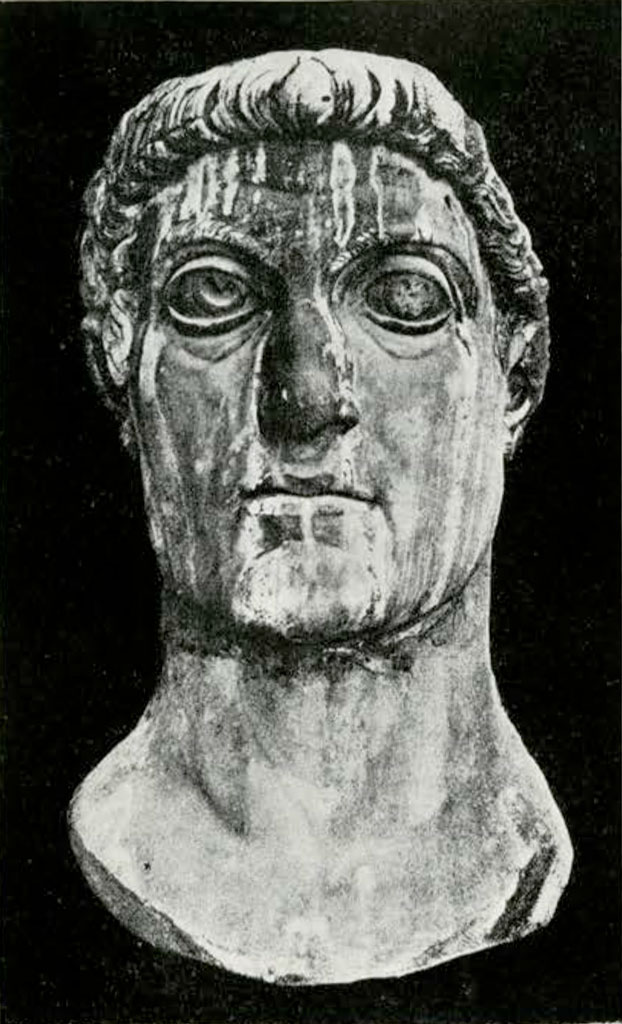

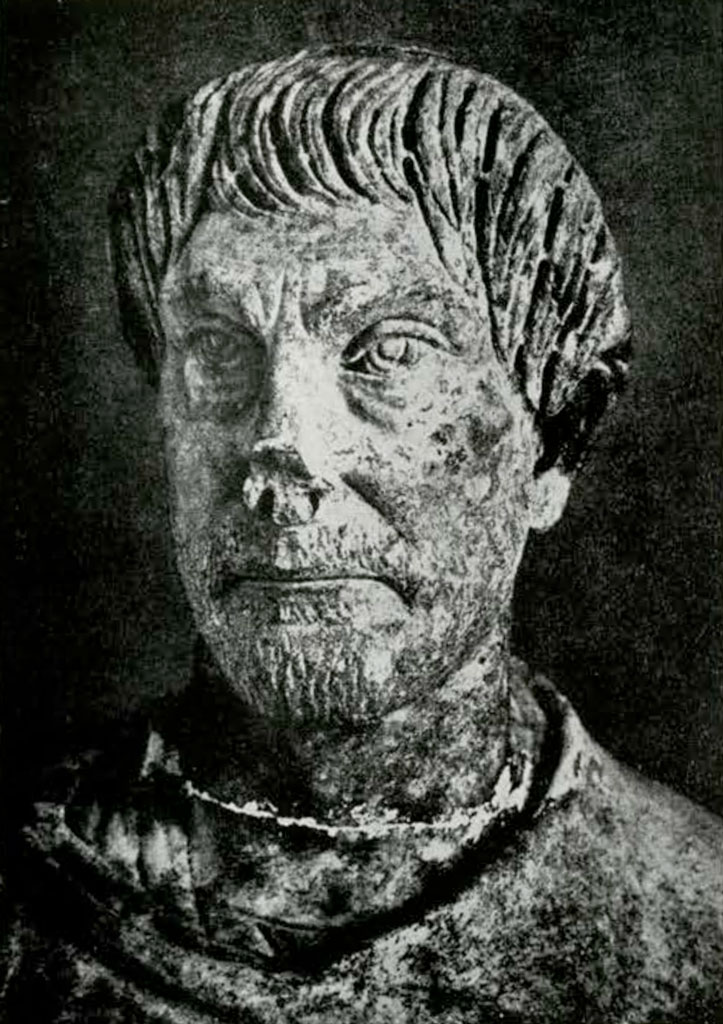

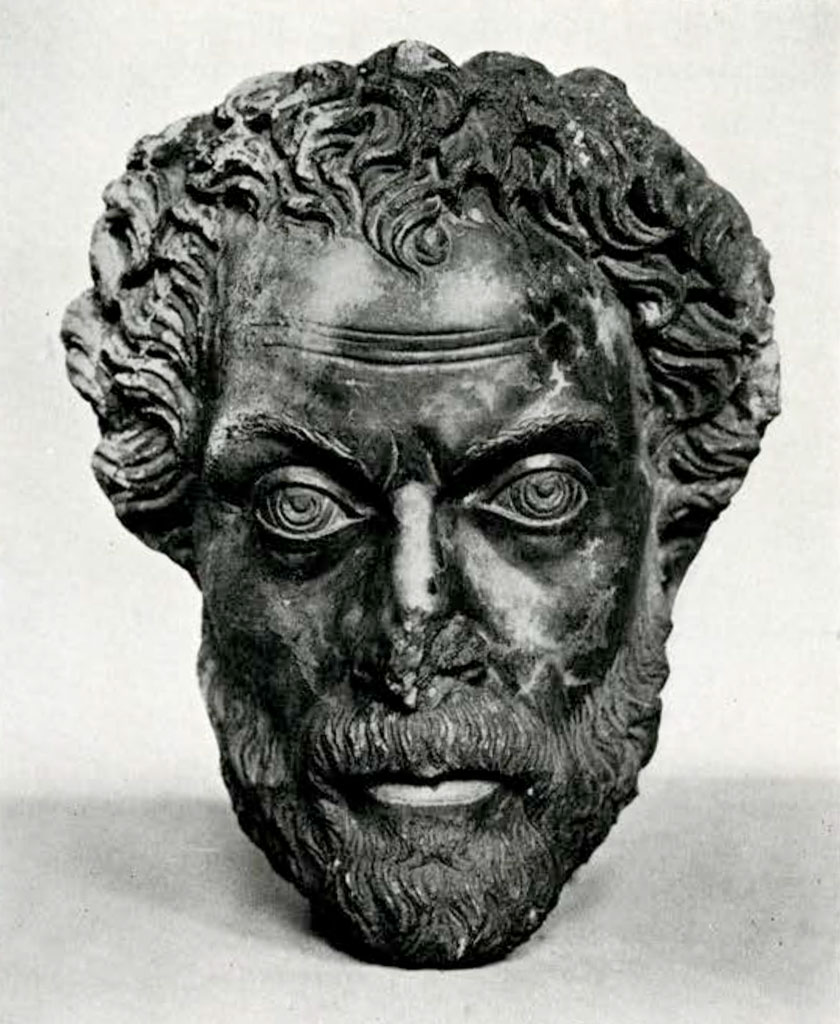

Styles of art change in conformance with the general evolution of the period. The whole unrest of the third century, political, social and mental, is represented in a head of the emperor Gallienus [Figure 1]. There is nothing but movement all over it; it is not only turned to the side but also tilted slightly upwards, and the look of the eye cuts at an oblique angle in the direction in which the head faces. The smooth flesh is in sharp contrast to the curls of the hair and of the beard. These are different in length and fall in irregular but distinct waves, whereas the small curls of the beard form a continually excited surface, the outline of which is an undulating curve. The eyelids and the wrinkles on nose and forehead are sharp and hard lines, which cut the soft flesh. The relief is high, the eyes are deep set, the curls of the hair are undercut; beneath the lip is a hollow, so that deep shadows break the light surface into contrasting parts. Then the change took place; the head of Constantine [Figure 2] proves that he achieved his task and consolidated the empire. There is no turn either to the right or to the left, but the head is directed straight forward. A rigid symmetry keeps all parts in an inflexible position, and a system of straight lines put together at right angles—that is, the lines of the eyes, the nose, the mouth—forms a backbone for the whole structure. The hair is a solid mass, giving no freedom to the individual curls, but moulding them by regular incisions into a decorative pattern which frames the forehead with a sharp and ornamental outline and forms a curve which frames the whole face. The lids of the eyes are extremely heavy and sharp and the eyebrows are emphasized by short parallel lines. The planes of forehead and of the cheeks are simple and large by reason of rigid subtraction of all but the main features. The result is monumental grandeur which breathes the calm security and sublime majesty of the unassailable ruler of the world. Whereas the look of Gallienus reveals a trace of pride, the last vestige of the classical appreciation of human beauty, the eyes of Constantine seek a spiritual world far above the vanities of life.

Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome

Image Number: 3287

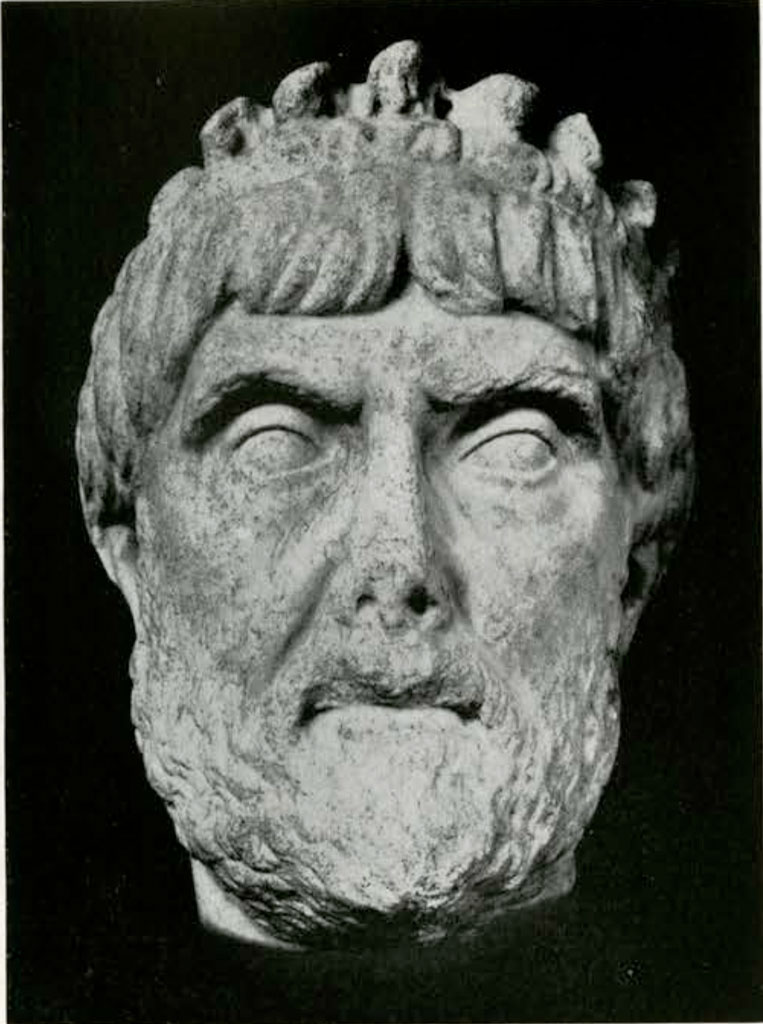

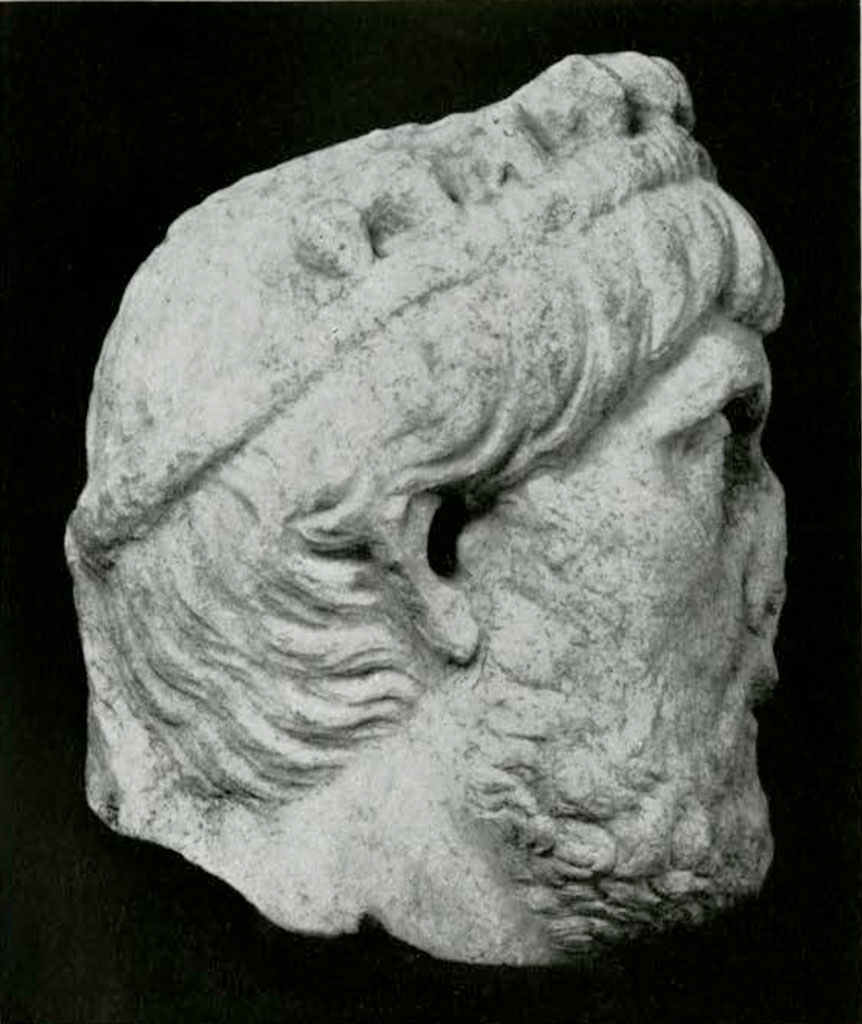

The University Museum possesses a fine head [M. S. 215 and Figures 3 and 4] dating from the same fourth century, as a comparison with the Constantine makes obvious at the first glance. We find the same frontality and the same architectural framework formed by the lines of deep shaded eyes, the nose, and mouth. The same symmetry which marks the face as a whole is found also in the hair with its division in the middle of the forehead and the regular locks to right and left. The expression, however, is slightly different, not because the head of Constantine depicts an emperor whereas the Philadelphia head represents a private man, but because of the interval of time which had changed the style. The tendency was towards a steadily increasing spiritualization. This is rendered by emphasizing the expression of the eyes, which become more and more the most important and striking feature of the whole face. At the same time there is a tendency to elongate the face from the eyes downward, the cheeks with their long smooth planes are no longer of the same value as the eyes but are used merely to set them off. Nature is no longer rendered in its true form as an organic structure, each part being allowed to have its own life, but is modified by an external principle which selects the forms according to the importance they have for expressing this principle. The Philadelphia head stands about half way between that of Constantine and the full development of the tendency which is shown by a head found in Asia Minor [Figure 5] and dated at the end of the fourth century. The incommensurability between body and soul, according to the contemporary dogma of the Christian faith, and the mastery of the flesh by the immaterial soul is now apparent. The look of the eyes is not the expression of natural forms but comes out of a transcendental world beyond them. A certain abstractness rules the face and changes the organic forms into mere schemes. Hair and beard are sketchy lines and the geometricized eyes miss the swelling roundness of nature. The head at Philadelphia obviously does not go so far in subduing nature to spirituality but preserves a more organic structure. Its date, therefore, can be fixed as approximately the middle of the fourth century A.D.

University Museum

Height .30 Metres

Museum Object Number: MS215

The art of the Roman Empire was not everywhere entirely homogeneous, but slight differences always existed between the art of the eastern and that of the western half. Comparing the head in Philadelphia with the one in Rome [Figure 6], dated some years earlier, we observe a difference as regards the conception of style by the artist. The Roman head shows sober realism. The forms are somewhat hard and sharp, they stick and cling where they are placed and lack a wider swinging and harmonious melting one with another. Short and strictly limited lines are incised into a hard and solid mass. The manner is cubistic and linear. The head in Philadelphia is built up in a different way. It seems to have a looser and less firm structure. The different parts, that is, bones, flesh, hair, are more independent, but, nevertheless, they correspond to each other and form, therefore, a harmonious whole. The lines are not sharp or hard, but are more rounded with soft and gently flowing curves. A remnant of the classical ideality seems to be preserved, now embodied in the new spiritual life, which—because not enforced by a powerful will. but an outcome of the whole personality and therefore relying on a solid background—breathes a full, free mastery of itself. This kind of style is rather Greek than Roman. An analogy in the rendering of the hair is found in a head now at Brussels coming from Aphrodisias in Asia Minor [Figure 7]. Especially the short finely carved locks of the beard and the form of the hair behind the ear are very similar, while the hair over the forehead is arranged in longer locks, besides the deeper incisions, not unlike those of the head referred to above. Also the striking naturalistic modeling of the cheeks is the same in the two heads in Philadelphia and Brussels. The attribution by style of the head in Philadelphia to the Greek art of Asia Minor is corroborated by the place of purchase, Constantinople, where it was bought by H.V. Hilprecht from a native of Caesarea. The condition is fairly good, the tip of the nose is broken off, and there are some damages to the mouth and erosion of hair and beard. The pupils of the eyes are represented by circular hollows carved in.

University Museum

Museum Object Number: MS215

Image Number: 3189

Having fixed the date and artistic school to which the head belongs, we have to look at the personality represented. This is indicated by the peculiar crown on the head: on a thick ribbon eleven human busts representing deities are placed, the middle one of which is just above the division of the front hair and emphasizes the axis of the head. Such crowns were worn by priests; and several examples with the same adornments as ours are preserved, coming also from Asia Minor. The man is therefore a pagan priest. Paganism was not abolished by Constantine, but, after having seen a renaissance under Julian the Apostate, lasted until A.D., 390 when Theodosius prohibited the sacrifices. Paganism had undergone also a deep change since classical times, and the art of the fourth century proves that there is not a difference between a specific Christian style and a pagan one, but a uniform development. Paganism, too, has been spiritualized. Our portrait shows a distinguished, highly educated man, without doubt, gifted with oratorial talent, very common at that time among pagan as well as Christian priests. Deeply imbued with the Greek philosophy, lie was a fervid defender of the faith in the service of which he is represented and a powerful personality showing an austere earnestness and an inflexible conviction. However, the deep set eyes with the dark hollows above reveal disappointment and uneasiness; lie adhered to a dying world soon to be overwhelmed forever.

For the permission to publish the new head and for other help in writing this article I sin deeply indebted to Mrs. E. H. Dohan, of the University Museum. The height from the chin to the top of the central bust of the crown is 30 centimeters. The heads referred to are published by Delbrueck, Antike Portriits, Kaschnitz in hit valuable paper on late Roman Art in Antike II, Schede in Meisterwerke der Türkischen Museen in Konstuntinopel I, and Rodenwaldt in his splendid article 76. Berliner Winckelmanns Programm. Consult also Riegl’s Spätrömische Kunstindustrie; Strong, Scultura Romana, Berliner Museum, July-August, 1923, 53 ff., and the 86. Berliner Winckelmanns Programm. My thanks are due also to the Direction of the Musées du Cinquentenaire who kindly furnished the photograph of the head at Brussels. For the crown, see Hill in Jahreshefte d. oesterreich. arch. Institute II, 1899, 245 ff., and Stegmann, Archaeol. Anzeig., 1930, 2.

Image Number: 3279

Musées du Cinquentenaire, Brussels