ONE of the most interesting and useful developments in the activities of the Museum is the co-operative work which is being carried on with the schools of the city. The idea is one which is by no means new in museums in this country and in Europe receiving support from municipal sources. If the school work which has just been inaugurated here has any unique feature it is to be found in the fact that this Museum receives no support from the city. The experiment has been the result of a desire on the part of the authorities of the University Museum to extend its educational influence beyond the confines of the University and to enable all the educational interests in the city to avail themselves of the opportunities which the Museum presents. The initial step was taken in December, 1911, when an invitation was sent through the District Superintendents as follows.

“The University Museum is situated at the corner of Thirty-third and Spruce Streets, opposite Franklin Field. Its object is to illustrate the history of man-kind. In its halls the visitor is brought

in close contact with the different peoples of the world. In arranging the exhibition, one of the objects always kept in view has been to bring vividly before the eye the various peoples that children read about in their books. For the schools they are especially adapted to the teaching of history, language and geography.

Image Number: 10989

“Here is an example. In the halls containing the exhibitions illustrating the American Indians, the children can see how the Indians lived at the time of Columbus and Penn, and how they fought the white man in his settlement of America, first in the east and later in the west. They can see how the Indian children were brought up, the toys they used, the games they played, how they dressed and how they became men and women.

“In the same manner may be read the stories of Egypt, Babylonia, Greece and Rome, Japan and China, Mexico and Peru and the wild tribes of Borneo, Australia, Oceania and Africa.

“These exhibitions are being constantly enlarged, and no pains are spared to procure the best, and to make them so attractive that the lesson which they have to teach becomes a pleasure and a recreation. One of the first objects of the University Museum is to lighten the task of the schoolroom, both for the teacher and for the pupil.

“The teachers are invited to bring their classes to the Museum, where every-thing will be done to stimulate the interest of the children in their studies. It is the object of the authorities to make these visits pleasant and entertaining. The curators and their assistants, especially trained for the purpose, will meet the classes and talk to them in the simplest and most telling language about the collections, explaining their uses and their special connection with the subjects that the children may be studying.

“Lectures, illustrated by lantern slides, will be given at any time in the auditorium of the Museum at the request of any teacher who will send notice to the director of the Museum twenty-four hours before the time selected for bringing the class.”

Image Number: 10992

In making this experiment the Museum has had the cordial support of the Superintendent of Education and from the start the principals and teachers have shown by their response how highly they value the Museum’s action. Last year the invitation was sent out rather late in the season, which prevented many teachers from making appointments. Notwithstanding this the result was decidedly encouraging. From January to June 1,331 pupils were brought to the Museum in classes by their teachers. These classes ranged from the Third Year of the Elementary Schools to the Fourth Year of the High Schools. The teacher bringing the class in each case selected the subject to be illustrated and the following list will show the scope of these Museum lessons and will serve to indicate the variety of interests in the public schools which can be helped by the Museum.

The American Indians.

The people of Borneo.

The peoples of Oceania.

The peoples of Africa.

The peoples of China and Japan.

The peoples of Europe.

The peoples of Asia.

Ancient Greece and Rome.

Ancient Egypt and Babylonia.

The world’s peoples.

The habits of primitive man.

In each case the talk was adjusted to the grade of the school and the kind and amount of instruction the pupils had received. In this adjustment and in the ability of the lecturer to adapt the talk to the mental attitude of the children consist the secret of success. The appeal which this work makes to the children depends upon the reality of the things which they see and of which they are told and the closeness of the association between these things and the mental experiences of the children themselves. Our practice has been by means of wellselected lantern slides and by a series of objects from the people dealt with, to bring that people vividly before the children’s minds and to enable them to feel themselves in close touch with the life of that people, whether belonging to a period 5,000 years ago or in our own time.

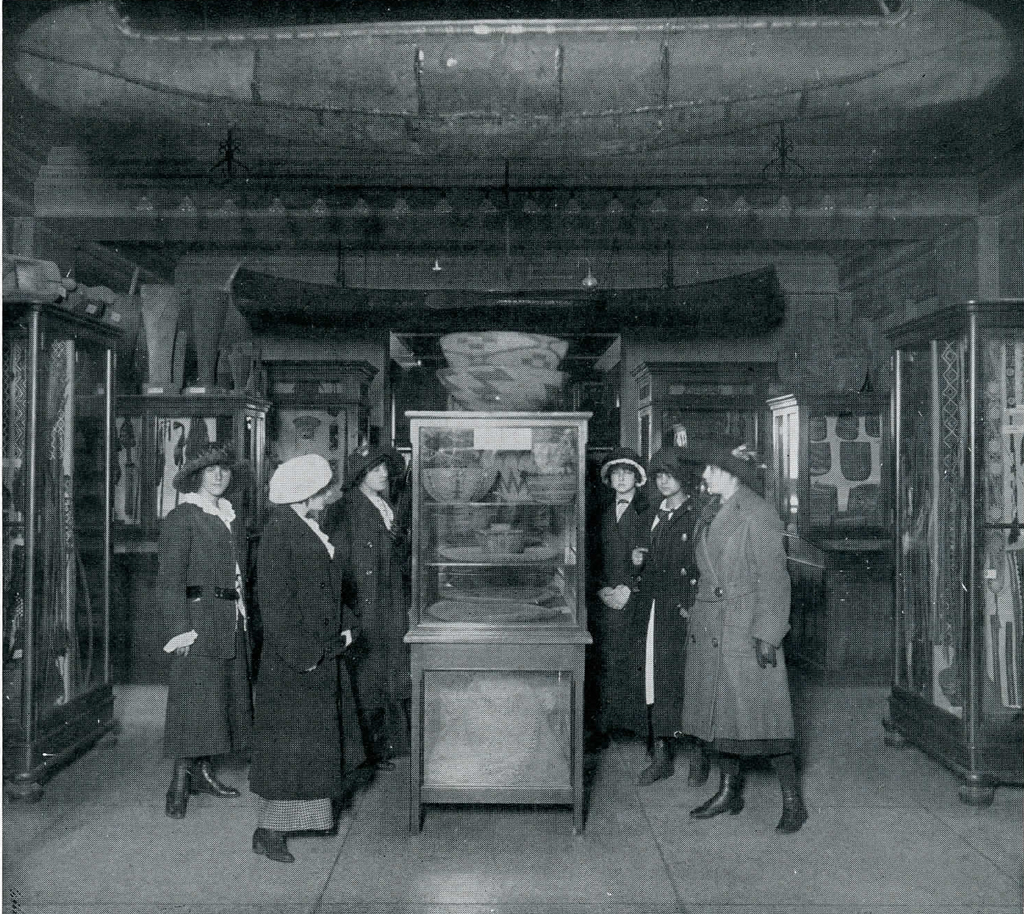

In the practical working of the scheme classes are first entertained by a forty minute talk with lantern slides. On the platform are placed a series of thirty or forty selected objects of common use among the people under discussion. After the lantern slides have given a vivid impression of the personal appearance of the people, their habitations and surroundings, these objects are taken one by one and explained to the children with reference to their origin, use and method of manufacture. In the case of objects which can be handled without risk of damage, they are often passed around among the children, for one of the attributes of the young mind is a love of handling things, an instinct which when gratified enables children more easily to realize the meaning of an object. This lecture room performance is calculated to last an hour, but usually the interest of the children is so stimulated at the end of an hour that the sessions last from an hour and a half to two hours. ‘For the younger children, the teachers in a great majority of cases select the American Indian. This has proved a wise and judicious selection for several reasons. All children are interested in the Indians and have their imagination stimulated by the mere mention of an Indian. The collections in the Museum, and notably the George G. Heye Collection, are especially well fitted to illustrate the life of the Indians. As shown by these collections, the Indian children, with their pretty dolls and clever playthings, their sports and lively games, furnish topics that make these talks as pleasant for the instructor as for the pupils. Again, the classes that select the Indian for their subject are privileged to see and talk with an Indian man and woman who are always on hand to conduct them through the exhibition rooms at the conclusion of each lecture. Mr. Louis Shotridge, a Chilkat Indian employed in the Museum, and Mrs. Shotridge, dressed in the costume appropriate to the Indians of the plains, have taken an active part in this class work, moving among the children and answering the many questions asked them. It must be said that this particular feature has proved immensely popular with the children, who immediately become greatly. attached to the Indians and establish at once the most friendly relations.

Image Number: 141709, 10991

The higher grades are apt to choose the ancient civilizations, and even if the peoples of antiquity cannot be made visible by the presence of living representatives, they can, nevertheless, be made very real by means of the Museum’s collection, as well as by lantern slides. In every instance, whatever the subject chosen, the teachers have expressed the greatest approval and the children have never failed to enter thoroughly into the spirit of the work.

In order to test the effect of these exercises on the children’s minds and the reliability of their memories, one of the schools participating in the work was asked to request the children to write essays on what they had seen and been told in the Museum. The teachers of another school requested the boys and girls to draw pictures illustrating some phase of primitive life or some particular primitive invention and to explain the device in a few words. The Wharton School, which contributed the essays, sent in a large number of compositions which showed a high average of intelligence in the children and proved the permanent value of our work by the reliability of their memories and the accuracy with which the ideas imparted to them were usually reported. The Brooks School, which was selected for the drawings, also made a return which was particularly pleasing for the skill and good taste shown in the water-color drawings made by the children and in the faithfulness of their memories. In both essays and drawings no one could fail to detect the stimulating influence upon the pupils of having seen and handled the rare and curious objects which come from remote parts of the world or from the distant past. They are being helped to observe for themselves how other people think and act under conditions different from our own.

The humanizing influence of this method of instruction and of these excursions into the past history of our race and into the habitations of unfamiliar peoples, often in a lower state of culture than ourselves, is, in the end, the highest and noblest effect of the Museum’s educational work among the school children.

So long as the teachers continue to co-operate with the Museum by bringing their classes here, so long as they enable us to feel by their interest and enthusiasm that our work is of value to them and helps the educational work entrusted to them, so long will this Museum be able to afford the school children of Philadelphia many desirable things and many pleasures which they would otherwise be denied.

G. B. G.