THE story of the archaeological discoveries in Crete is now ten years old. Even our school-boys are learning to-day that the labyrinth of Minos has been found and that it was a palace three stories high, with open courts and winding corridors, with storehouses for treasure, a well equipped bath-room and a suite of apartments for the queen that would compare favorably with those of a high-born woman of to-day. But the tale is not yet told. We cannot read the writing of this far-away people of 2000 B. C. We do not know whence they came or whither they later went or how they were related to the Greeks of Pericles’ time. All this must be learned by the spade. Only by the patient excavation of site after site can such problems be solved, and it is to the lasting credit of the University Museum and of the people of Philadelphia that they have understood this and have made possible further explorations in Crete.

Two years ago I commenced excavating for the Museum a town situated on a steep and lofty mountain-crag in eastern Crete where the successors of Minos had lived in the clays of their declining power. It was in a wild and rugged district where our ponies could scarcely make their way over boulders and along dizzy ledges, and where it was difficult to find a level spot big enough to pitch my tent. Our faithful workmen had no other shelter than the small bush huts which they improvised for themselves, and their food was confined to bread and oil with an occasional dish of snails as a relish. But in spite of our hardships and difficulties we accomplished our end, for we found deep deposits of earth crammed with pottery, the very best evidence possible. It seemed, in fact, that we might learn from an extended excavation of this site, especially if we could also find the tombs, the answers to some of the vexed questions as to when and how the Minoan power fell, and it was with this purpose in mind that I returned to Crete last March.

Crete is not an island which is easy of access. This year I tried going by way of Egypt, but the same difficulties beset me as heretofore. The steamers were small and dirty and we were landed in rowboats at 1 A. M. in a heavy sea. It was two days before my companion and myself had sufficiently recovered from seasickness to start on our journey eastward. In the meantime I had opportunity to see the new accessions of the Candia museum and to arrange with the government for our excavation permit.

All traveling in Crete is done on horseback. Camp beds and the necessary food and clothing are carried on the pack-saddle of the muleteer. There is no pleasanter mode of travel. The Cretan pony gets over the ground easily with a quick, Crippling gait, and the grave courtesies and simple hospitality of the islanders are a never-failing source of pleasure. Such travel is not dear. Two francs will pay for the evening meal and an empty room in which the camp-bed may be set up. The Greek monasteries also make a practice of receiving guests, and these are the most delightful places to stop, for they are clean and are built in high and picturesque places. I visited one this year which was a miniature Amalfi. The abbot and monks will accept no pay, but the guest is expected to leave an offering before the eikon in the church.

Our museum is fortunate in being allowed to use as excavation headquarters the comfortable house of the director of these excavations, Mr. R. B. Seager, at Pacheia Ammos. Here we stayed until the rains were over, making ready to go into camp. There were tents to patch, stores and kitchen utensils to arrange for, and wheelbarrows and water barrels to overhaul. In the meantime we dug a few stray tombs at Kavousi, to which our attention had been called by our Kavousi workmen.

On the last of April we were ready. A Turkish caique brought the picks, spades and wheelbarrows as well as the tents and camp supplies to a cove at the foot of the mountain and from there our workmen, with the help of a few pack animals, carried them to a little plateau half way up the mountain, where we had decided to pitch our camp this year. A small stone hut was secured for a kitchen by the payment of ten francs for the season.

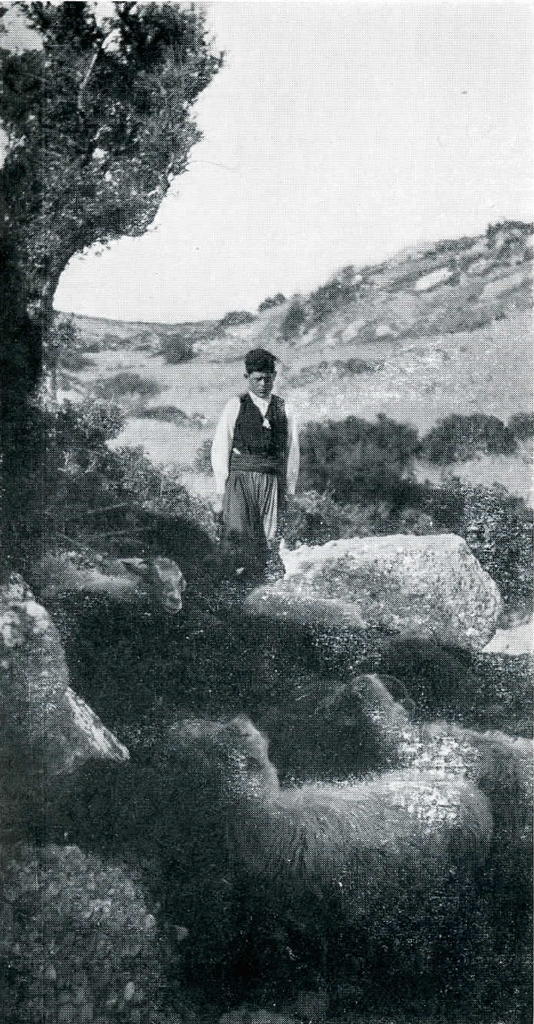

We had no neighbors save the shepherds who pastured their flocks close by, but every night and morning the well of water near my tent presented a lively scene when the women and children from the village below stopped to water their “possessions”—generally a donkey, a goat and a pig apiece—on their way to and from their fields. This well of water was, in fact, the social centre of the place, all the more so when the women learned that I would allow them to inspect my tent. Sometimes at evening when I rode home from work, I would find a dozen waiting for me to show them the wonders of my tent, which consisted of a camp bed, a table, and two chairs.

On May 1st we began digging in earnest with about fifty men. I set them first to clearing away brush and stones on the north face of the summit where unusually good walls were peering cut from among the bushes and where I thought well-preserved houses might be found. But I also started another project. Two years ago under the guy ropes of my tent I had noticed a heap of stones that looked like the top of a “bee-hive” tomb, but I had not investigated it because of the inconvenience of disturbing my tent. This year, however, I resolved to lose no time in trying this spot and sent one of the oldest and most trusted workmen there. The second day when on my rounds I visited him, he showed me a piece of bronze which I recognized as a piece of a foot from a very fine bronze tripod. He also pointed in triumph to a small pile of teeth and of human bones he had found. He had not yet cleared any of the walls of the tomb, but that it was indeed a tomb there could be no doubt. During the next week I spent most of my time sitting on the edge of this excavation, for every few minutes Nikolaos would hand me something, another piece of the tripod, a bronze safety-pin, a porcelain bead, or a bit of pottery. So much pottery came to light that we were able to put together forty vases, more than all the other workmen together found during that first week. The porcelain beads particularly interested me, for they looked to be Egyptian. I had already filled all the small boxes I had with them when Nikolaos, who was full of jokes about the value of beads in the next world, suddenly cried, “Behold, I have his seal too.” And sure enough, there was a porcelain seal with Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the same day he found five more. I cannot read hieroglyphs; we had, accordingly, to wait until two weeks later we chanced to have a visit from an English Egyptologist. He pronounced them to be commemorative probably of the XXII dynasty, from about 950-850 B.C. We had thus accomplished one of our purposes, for we had obtained evidence for dating the fall of the great Minoan civilization.

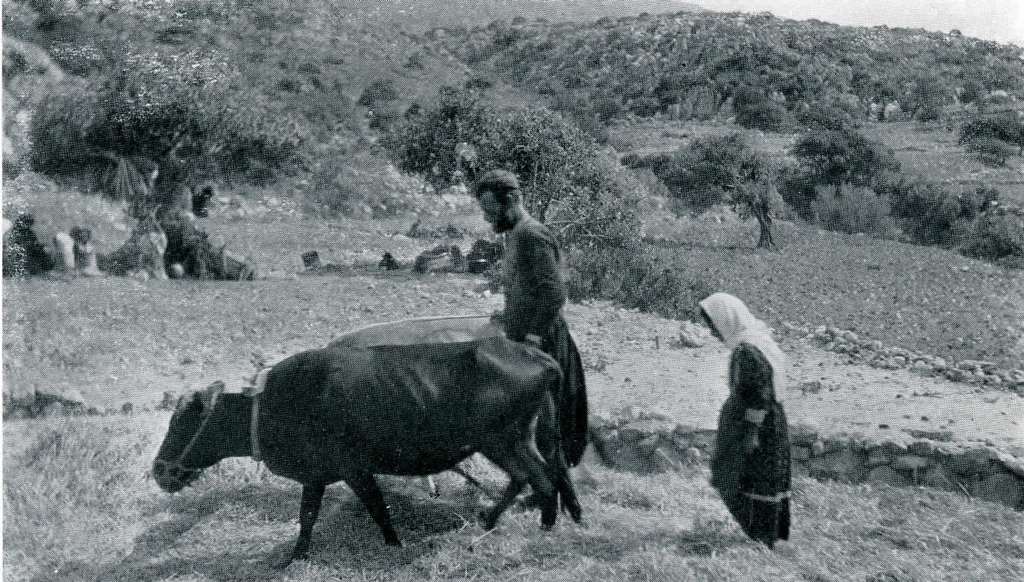

I had thought that with one tomb found the cemetery of our town was already discovered, and that it would be an easy matter to find more tombs. But such was not the case, for the tombs proved to be widely scattered. We spent days in digging trial trenches which yielded absolutely nothing. We did, however, find more in the end, six of the “bee-hive” type and at least fifty shallow graves which yielded quantities of vases and many bronze safety-pins or fibulæ. It is often said that Queen Victoria invented the safety-pin. But it was only a reinvention; it had been in use throughout the first millennium B.C. These pins, moreover, are of singular value to the archaeologist, for according to their shape and size the peoples who used them may be classified. We had therefore good evidence for the solution of the other archaeological problem as to who these people were. It was now the middle of June and the heat was exceedingly fierce. The women and children no longer returned to the village for the night, but whole families were camping in the fields for the harvesting season. Near every threshing-floor a family was encamped under a tree, while men, women and children helped with the work of reaping, threshing and winnowing, all of which is accomplished by the most primitive methods. We were daily visited at our tombs by these neighbors, who brought us fresh almonds, apricots and plums tied up in the corners of their aprons or handkerchiefs, and were delighted to receive in return presents of pins with colored heads.

Image Number: 143048

In spite of the heat there was one thing more to accomplish. One of our basket-boys had brought me excellent potsherds from a field in the plain below close to the sea, and I was eager to try there for a week to learn if it was a site worthy of further excavation another season. Unfortunately the Romans had been there before us, so that much of the pottery was badly broken. Some beautiful specimens of the very best period were, however, recovered during the week that the excavation lasted, and there is every evidence that much more lies hidden away beneath the earth.

But by this time our money was exhausted and we were obliged to send for the Turkish caique, in which all our goods and chattels together with our precious finds were shipped to the house.

A few days were spent there in sorting pottery and then I packed up the antiquities in fifteen cases and set sail with them in the small coasting steamer for Candia.

The authorities of the Candia Museum with their usual kindness gave me the use of a large cool basement room where I could spread out my pottery and bronzes on long tables. Here I worked for ten days, photographing and taking the final notes and measurements. The last task of all was to petition the Cretan government in the name of the University of Pennsylvania Museum for a consignment of the objects found. I asked for over sixty pieces which, if they are granted to us, will reach the Museum this autumn.

E. H. HALL.