Image Numbers: 153871, 32494, 32495

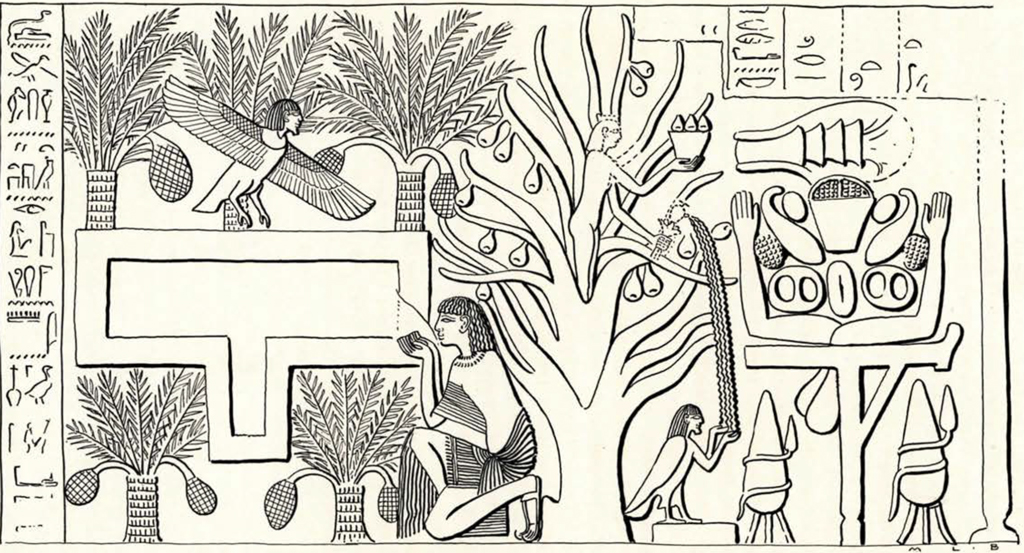

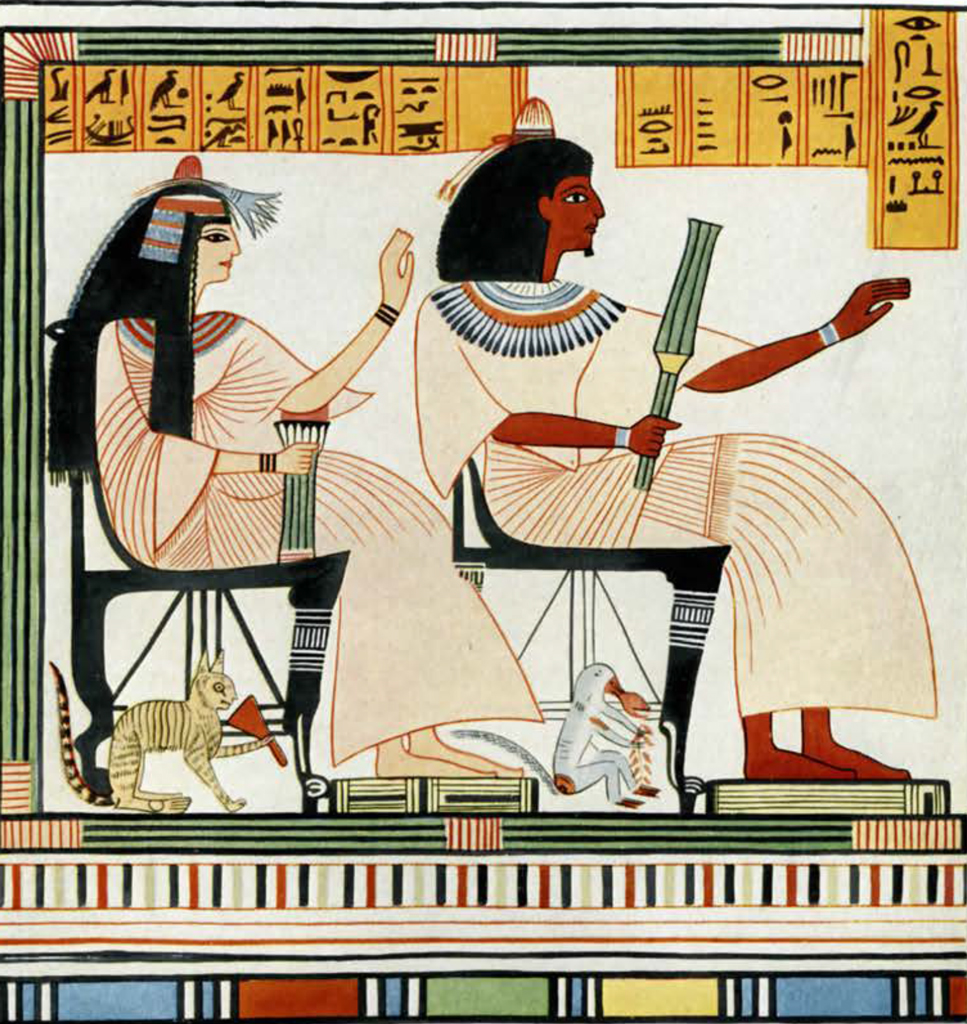

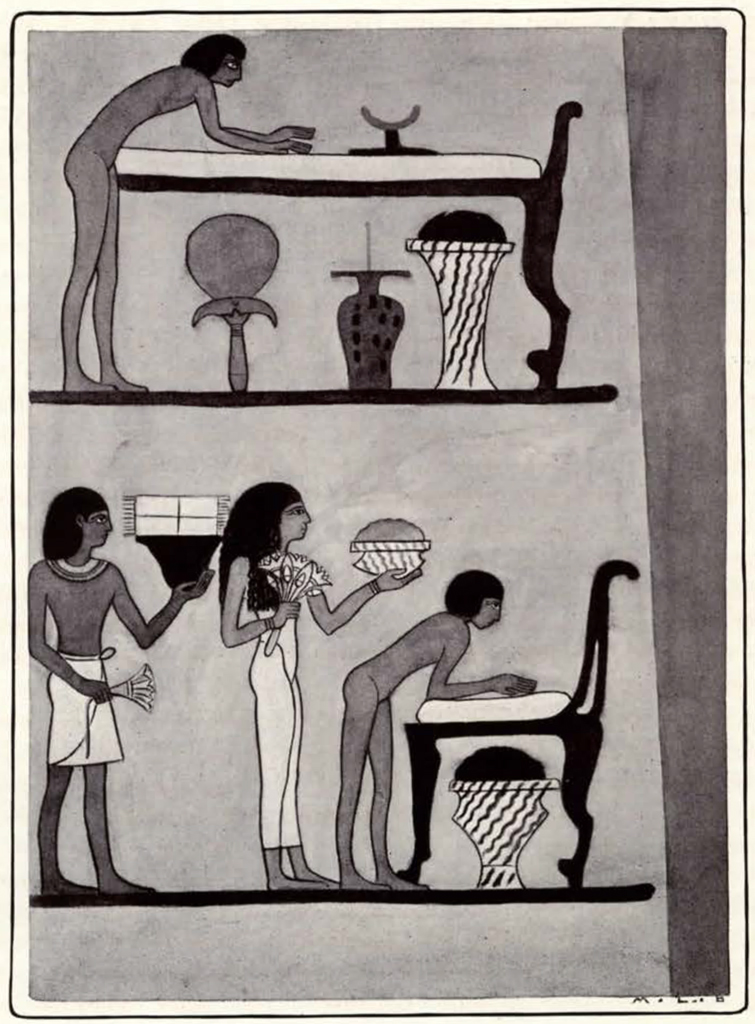

During the winter seasons of 1921-22 and 1922-23 the University Museum chose for its field of operations in Egypt a portion of the necropolis of Thebes. This cemetery stretches for several miles along the western bank of the Nile opposite Luxor and has rightly been considered for many ages one of the most important localities of its kind in Egypt. As early as 2200 B.C. it was the burial place of the mysterious Antef kings, who quarried with inestimable labour those enormous tombs which lie near the fields at the northern end of the area. Though used over a long period of time the cemetery attained its greatest extent and splendor between 1580-1090 B.C., when it became the necropolis of the Kings and Queens of the XVIIIth to XXth dynasties and their courtiers. Of this period we have an almost unbroken series of royal tombs of which the grandeur of conception, the scale of construction and above all the beauty and freshness of the interior decorations, cannot be equaled anywhere else in the world. So impressive are these sepulchres that they have rather overshadowed the many hundred smaller tombs built for the officials of the court of Thebes throughout this period. Of these only a very few are ever visited by tourists, yet in some ways they appeal to us much more strongly than do the royal tombs. Instead of the walls being covered exclusively with endless symbolic and mysterious religious scenes we find depicted on them not only a simplified series of views of the funeral procession in its various stages, with the mourning women and the array of offerings borne to the grave, but also many pictures illustrating the daily life of the people. These were drawn with exquisite grace and charmingly colored, with here and there touches of humor that give us a glimpse into the real underlying happiness of the people. The owner seated in a pavilion hung with garlands reviews his herds and flocks or overlooks the workers in the fields, ploughing, sowing and reaping. Or in the midst of his family at home, he enjoys himself with singing, dancing and feasting. Occasionally he indulges in his favorite pastime, a hunting trip on the river, when he snares the water fowl, spears the fish or even goes after the larger game that lurked along the reed covered banks. His employees on the estate go through their various occupations, gathering grapes and pressing out the wine, salting the fish and fowls for future use, or engage in making up the different articles which they need in their work. They are very human documents and enable us to reconstruct a fairly complete picture of the daily life in one of the richer households of the second millennium B.C., a routine that really varied little except in minor details during the whole period of dynastic Egyptian history.

Image Numbers: 198397, 32496

In addition to the cost of constructing his tomb, which he completed as far as possible during his life, the expense of the actual burial of a wealthy noble was so large as to have been a drain on his estate comparable to the death duties of today. We have recently learned how rich and elaborate was the equipment supplied for the tomb of one of the lesser known kings of Egypt, and it was the hope of all officers of state, to emulate the king in this so far as their rank and wealth permitted. The preparation for the funeral occupied several months. Furniture had to be made like that actually used during life, chests of fine linen and clothing were made ready, with statues of the deceased and of the protective dieties, the latter usually enclosed in elaborately carved and gilded shrines, and a vast quantity of smaller objects such as walking sticks, jars of ointment and incense and supplies of food, were collected and placed in the chambers of the tomb. When we add to the cost of these the value of the gold ornaments and the precious jewels that were also buried, we realize the amount of wealth that was disposed of annually for this purpose.

It was one of the fundamental requisites in Egyptian religious beliefs that the body of the deceased should be preserved intact throughout eternity, and much pains and ingenuity were expended to accomplish this end. Tombs were constructed with false doors and misleading passages so that the location of the actual tomb chamber was concealed. But the knowledge that such riches were concealed in the Theban cemetery did not lessen the possibility of spoliation. Even at a very early date in Egyptian history there were persons willing to risk the wrath of the gods and incur the severest earthly penalties to enrich themselves with the spoils of the dead. Our former excavations at Gizeh and Dendereh showed us that even the undertakers entrusted with the disposal of the corpse in its final resting place were not disinterested. Bodies have been found in sealed tombs and in coffins with the lids still undisturbed, with their hands, feet and heads severed so that the jewelry and ornaments could be removed quickly. Having done this at the last moment, the workmen covered up the traces and departed with their loot, never failing to collect in addition the amount due them for their services from the family. During the reigns of the later Ramesside pharaohs the systematic plundering of the Theban tombs by organized bands became such a public scandal that a commission was appointed to investigate the matter. The thieves were rounded up and the official records containing the evidence submitted by them have survived, recorded on rolls of papyri. The robbers did not spare any labour in attaining their ends. After finding one tomb in the midst of a group, they tunneled underground to an adjoining one and thus could loot a whole row of chambers without their work becoming apparent to any one on the outside. There were of course special guards residing in the cemetery to protect it against such depredations but we can well believe that it was not difficult to secure their absence at the critical time by some division of the spoils.

Image Number: 34929

While these people took away an immense quantity of valuable material, they had no use for the heavier objects, the stone and wooden coffins, and furniture. They were careful to leave these apparently as intact as possible in order to conceal their depredations from a chance honest inspector. Later tomb robbers have not been so considerate. During the Middle Ages there arose in Europe a demand for the bitumen with which the mummies had been prepared, as it was supposed to have some medicinal value. The cemeteries were the only source of supply for this and countless tombs were searched for the bodies which were then ripped to pieces and hopelessly destroyed. Later still the wooden equipment as well began to have a commercial value, and the great Arabic scholar, Edward W. Lane, while staying at Luxor, records that his meals were prepared over a fire replenished with pieces of gorgeously decorated sarcophagi brought by the donkey load from across the river. The final phase came with the advent of the modern tourist and his demand for souvenirs of his visit. To this period we owe the wholesale destruction of the decorations on the walls themselves, as many beautiful reliefs were wantonly mutilated to secure one coveted head. Happily the native has now discovered that it is far more profitable and less risky to pass off upon the tourist an excellent forgery which gives just as much satisfaction to the purchaser. When we consider the long period of systematic destruction to which the Theban tombs have been subjected, our wonder is not that there are so few of them left with their contents in whole or in part intact, but that there are any left at all.

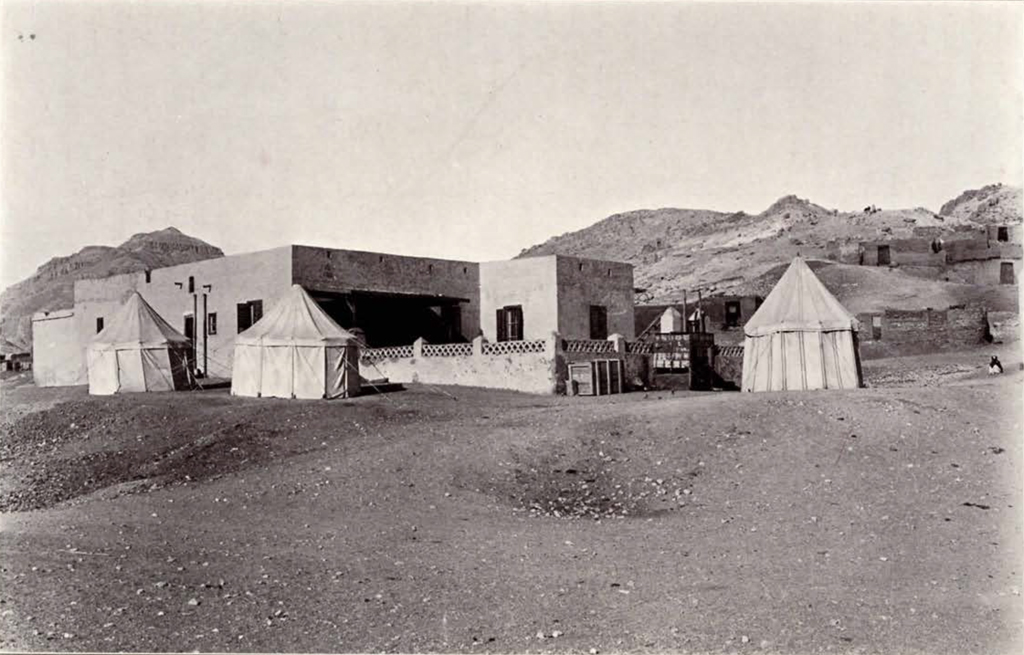

The Museum’s concession included a portion of the cemetery area. It extended from the long causeway leading up to the Temple of Hatshepsut at Der-el Bahri, eastward along the main cliff as far as the deep ravine which cuts deeply into it at the village of Dra-abul-Neggah. The northern boundary followed the watershed of the cliff, adjoining Lord Carnarvon’s concession to the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings, the entrance to which lay but a short distance to the north of our headquarters. The east and west boundaries gradually converged towards the south until they just included the small mortuary temple of Queen Aahmes-nefret-ari at the edge of the cultivation near the Seti I Temple.

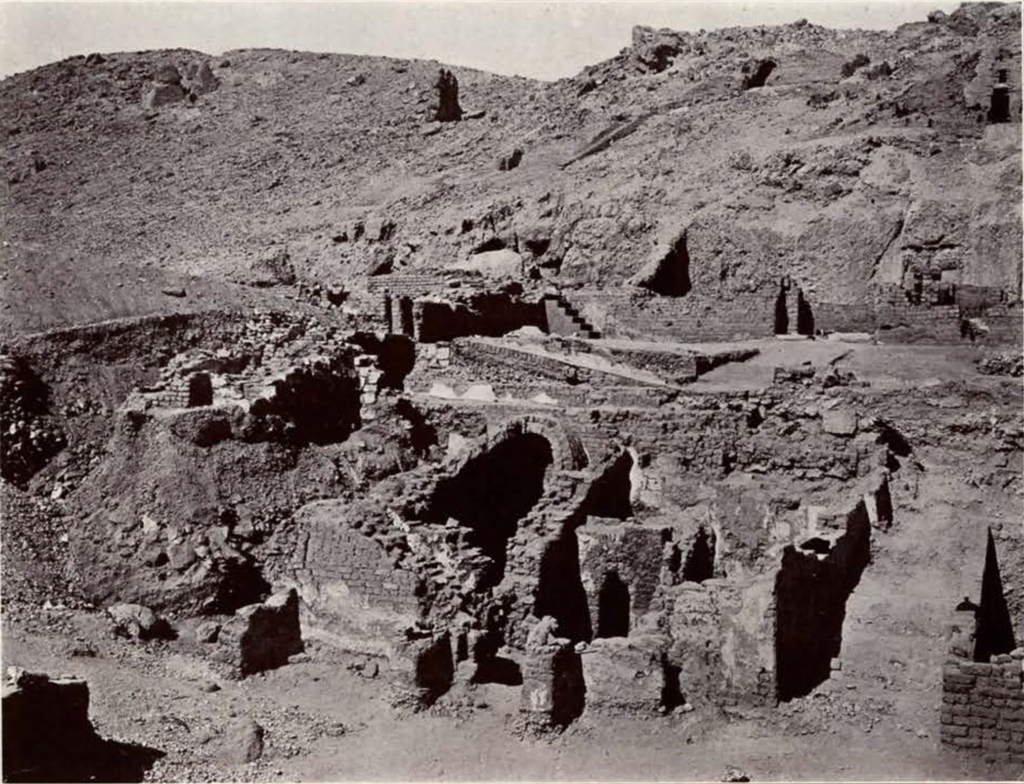

Within these limits, as in most other parts of the necropolis, one may divide topographically the tombs into two groups, which for convenience may be designated as the Upper and Lower cemeteries. The Upper cemetery included only those tombs which had been cut into the sloping sides of the cliff, and as this was considered the choice position during the New Empire, it was preempted by the high priests of Amon, and such of the higher military and civil officers as had sufficient influence to get a burial lot there. The Lower cemetery lay between the foot of the cliff and the edge of the cultivation and contained only the graves of the minor dignitaries and those who could find no place on the slopes above. The efforts of the Expedition were directed principally to clearing the large tombs in the Upper cemetery and the work here occupied most of the time during the two seasons. During the second year, time was found to clear a long strip of the Lower cemetery including the whole of the Aahmes-nefret-ari Temple and a small part of a mound called the Mandara situated at the mouth of the deep ravine forming the eastern boundary.

Image Number: 34822

In our portion of the Upper cemetery, the slope of the cliff was broken about half way up by a narrow terrace which extended fairly level for several hundred feet and then gradually sloped down into gullies at the east and west. The lower slope was practically covered with the mud brick houses of the modern Arab town of Dra-abul-neggah, in each case a house marking the position of a tomb. The entire village owes its existence to the fact that in this district, excessively hot in summer, a cool subterranean chamber is a necessary adjunct to a dwelling, and the rock caverns were a cheap and easy way of obtaining it. When not used for sleeping they made fine stables and storerooms for crops. The chance of finding treasure was also an added incentive for the selection. So whenever a man discovered such a tomb he immediately staked off a building lot in front of it and by this occupation acquired a legal title to the property. The government is now making arrangements to move the entire village to a new site down near the fields so that what little remains of the decorated walls of these tombs may be protected and preserved.

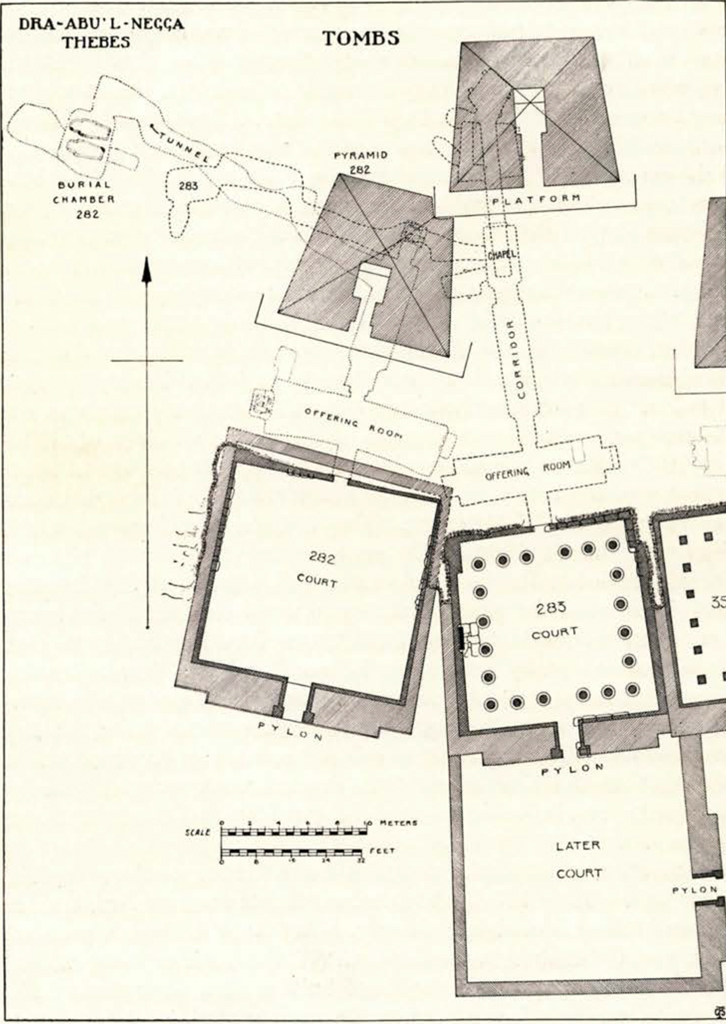

From a preliminary investigation of the site it appeared unlikely that any tombs of importance could exist in the western gully. The whole of the rock below the level of the terrace consisted of a poor loose conglomerate which must have rendered tomb cutting extremely dangerous and unsatisfactory. A few small tombs which had been found here previously proved this. The more likely area lay to the east. First the surface of the terrace was tested over a considerable space, no graves of any sort being found to the west of a large rock tomb, No. 282, which already lay open. This made available a large area for the dumping of rubbish from any tombs that might be cleared. From No. 282 the work of clearing the whole surface was then carried across the face of the hill. Almost at once there were interesting developments. The eastern gully was longer than at first appeared and its upper end had become filled up with a mass of broken stone and chips thrown into it at some stage in the construction of the large tombs above. This mass had completely buried several small tombs. It had been supposed that a Theban tomb consisted merely of the chambers cut in the rock, but as the space in front of No. 282 gradually opened up, it was found that there was a large square court in front of the rock portion with a monumental gateway or pylon. During the early centuries of our era this court had been built over with small mud brick houses, and according to a number of ostraka of stone and pottery with religious inscriptions found in them these must have been the habitations of Christian monks. As the work progressed similar features were found in a number of the tombs and gradually the whole cemetery disclosed a group of Ramesside tombs complete with forecourts, rock chambers and superimposed pyramids.

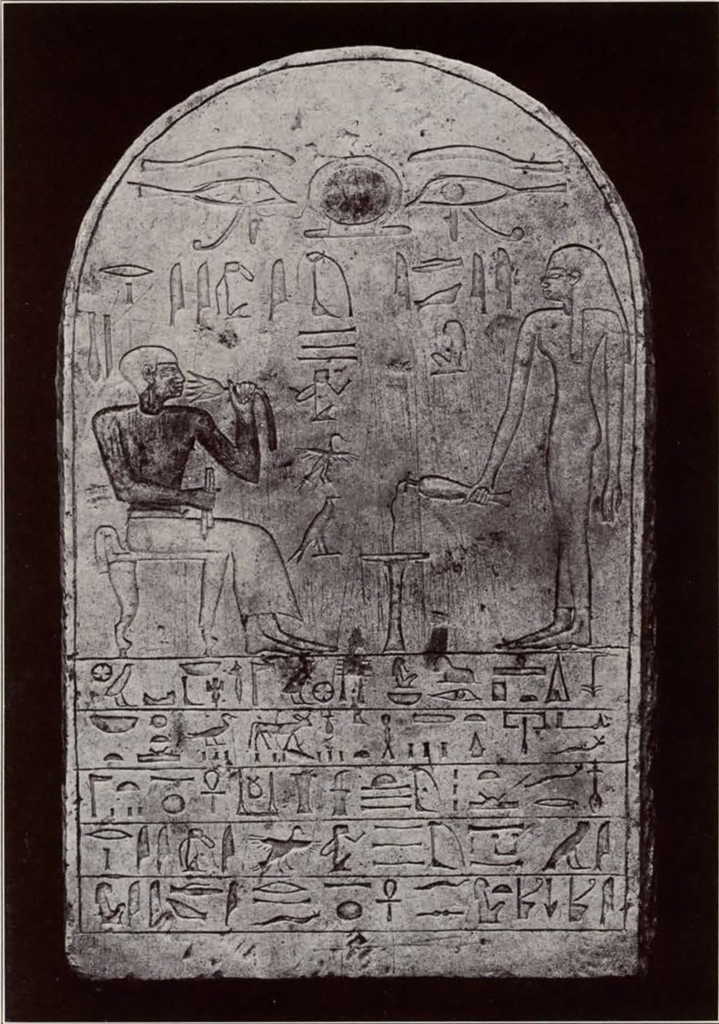

Tomb 282 had a plan which was typical of the Ramesside group. It belonged to Haqa.Nakht or Nakht, who not only was a royal scribe, but also bore the titles of Chief Archer of Kush, Desert Overseer of the Southlands and a Fan Bearer on the right of his Majesty (Ramses II). In making the tomb a trench somewhat wider than the proposed court was driven into the sloping face of the hill until the depth of rock reached was sufficient to contain the height of the entrance and also allow space for the thickness of the roof. In this instance the cutting was 54 feet wide and the scarp at the inner end 18 feet high. The space thus obtained became part of the court and the plan was completed by extending the lines of the sides with walls of sun dried brick and filling in the fourth side, towards the valley, with a large pylon gateway. The brickwork was built against the face of the rock, so as to mask all the irregularities left by the quarrymen. All masonry was probably erected after the rock chambers had been completely cut out and the debris removed. After the brick walls were in place the floor of the court was paved with slabs of stone. A line was marked several inches inside the face of the brickwork on this, first with red and then slightly picked out with a chisel, to serve as a guide to the masons in placing a final casing of stone over the walls. In No. 282 the casing was carried around all four sides of the court and through the door but not along the exterior of the pylon which was finished with white stucco to imitate stone. The entire pavement of this area had been removed leaving only some of the slabs in position around the sides. No evidence of any piers or columns around the court remained, but as the size and shape of the court was similar to that of the adjoning tomb, 283, which had a colonnade around the court, such a feature doubtless existed here. Only a few fragments of the relief and colored decoration on the walls of the court were found in the debris as the fine casing provided excellent material for later builders. At the centre of the south side of the court, that is, on the left as one entered it, had stood the main funerary stela of the owner, a slab of limestone or sandstone, sometimes colored to represent red granite, from three to five feet high and half as wide, with a rounded top. On it was a relief or painted panel showing the deceased presenting his offerings to Osiris, with a long inscription below giving name, titles and prayers to the god for his proper arrival and happiness in the next world. Sometimes this stela was erected in a shallow niche left for it in the masonry.

Image Number: 34801

From this court a door led to the offering chamber which with all the succeeding chambers was cut wholly in the rock. The first chamber extended crosswise of the tomb and in No. 282 was 41 feet long and 11 feet wide, with a slightly vaulted ceiling. At either end were cut deep alcoves, with figures of the owner and his wife seated. The woman was placed at the right of her husband, with her left arm around his neck. When working in poor rock the masons often had to contend with difficulties. Embedded in the conglomerate were large boulders of hard stone, which if removed would have left awkward cavities in the sides or brought down upon them the whole ceiling. On the other hand the stones were too hard to chip off and they were left projecting from the walls or ceiling. Large fissures in the rock and all the deeper irregularities were blocked up with stones and bricks, and the rough face of the rock was evened up with a thick layer of mud mortar containing plenty of cut straw. Over this was a finishing coat of fine white stucco, on which was painted the decoration. The general scheme was blocked out by the master painter, who then placed the task of working out the details and applying the color in the hands of his assistants. Either as suggestions to his assistants or as studies for the heads of figures, small sketches were often made on a fragment of stone or pottery. During the progress of the work, he would make periodical rounds of inspection and sometimes finding a figure out of scale or an arm or leg not properly drawn, he would correct it, leaving both the original and the revised outlines. The decoration, as has been said, consisted of domestic and agricultural scenes or the owner making flower and food offerings before Osiris. A large portion of space was given up to showing the progress in the journey of the departed into the next world. Mingled with the drawings were long inscriptions repeating over and over again religious formula and texts. The ceilings were always charming. Within a wide border of lotus flowers and coloured bands, the surface was divided into an even number of squares, each one filled with its own separate all over pattern of conventional leaves, spirals or flowers, arranged with admirable care and harmoniously colored. From the first chamber a long corridor led at right angles into the rock ending in a small chapel or offering niche, containing another pair of seated statues. On the left side of the corridor near this chapel a rough door opened on to a tunnel winding down to the burial chamber often many feet below the level of the offering rooms. Except in one very large and elaborate tomb to be described later, the tunnels and burial chambers were left in a rough state and the walls never finished or decorated. The burial chamber contained one or more sarcophagi which had been hauled into position before the death of the owner. The lids were also made ready and placed in narrow side alcoves, where they lay out of the way until the interment took place, when they could easily be slid into position. In No. 282, the two sarcophagi were of red granite. Both had been broken open and parts of the covers demolished. In one was a second case of finely finished stone, but no traces remained of the inner wooden coffin with the cartonnage enclosing the mummy. After the burial was placed in its coffin the opening from the corridor was sealed with masonry and the surface plastered over to correspond with the walls of the corridor. It was plainly the object to conceal the exact position of this entrance, that the burials should remain undisturbed, but the work was often crudely done and the ancient robbers working with some knowledge of the plan of such a tomb, knew approximately where to look for it. Sometimes they missed the opening by several feet but as soon as they realized their error, they turned their own tunnel until it joined the older one. In several of the tombs a false door was carved opposite the actual one so as to mislead any plunderers.

Image Numbers: 32503, 32504, 32505, 32506

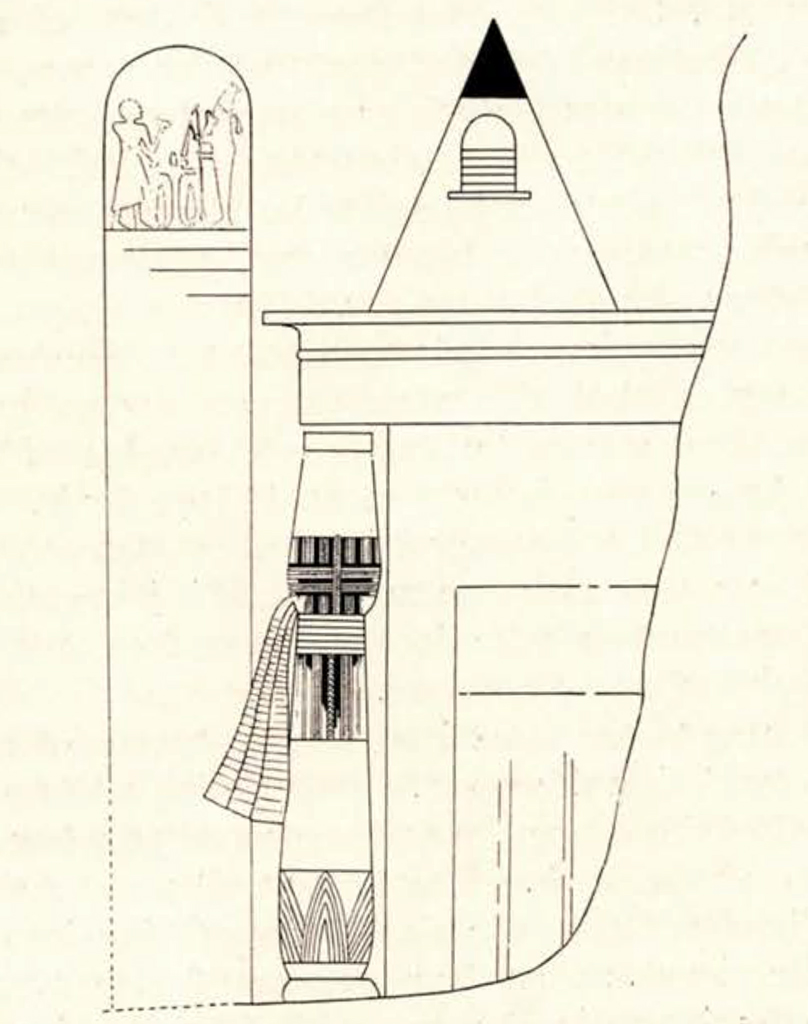

We now turn to the most important external feature of these tombs. In completing the court, the enclosing walls were carried above the roof of the colonnade and continued as a low wall across the rock scarp at the back. The latter wall prevented any earth and stones dislodged from the slope above falling into the court. Higher up the slope and as nearly as practicable over the inner chapel of the tomb was built a pyramid of brick. A narrow platform was first constructed to serve not only as an ornamental base as seen from the front, but also as a level surface on which to lay out accurately the front of the structure and thence work out more easily the other dimensions of the pyramid. The greater portion of the latter was built on the rough natural rock surface and considerable ingenuity had been displayed in its construction, as the successive courses of brick kept a uniformly horizontal level throughout the height of the structure, while the slope of the sides and the symmetry were well maintained. The pyramids are different from the familiar type at Giza belonging to the Old Empire. In the Ramesside type the shape is not so pleasing, the slope being much steeper, thus increasing the proportion of height to the width. They resemble more the pyramids of the still later Aethiopian period found in the Sudan. The pyramid contained a single small chapel, with a semicircular vault and entered through a round arched door. At the inner end was a ledge or altar and from such scanty traces of the coloured decoration that remained on the walls in two or three of the chambers they appeared to have been dedicated to Hathor.

In several of the tombs the sequence of funerary scenes finishes with a representation of the arrival of the mummy at the cemetery and being endowed with new life by Anubis before being placed in the burial chamber. At one side the artist shows the slope of the mountainside, sometimes with the head of the sacred Hathor cow peeping out. Against the slope is drawn the representation of the tomb, consisting of a facade with square entrance behind a colonnade of which but one column is shown. Just outside stands the round top funerary stela. Above rises the tall pyramid with its round arched door. Now the Egyptian artist was limited in his means of showing three dimensions. He had no idea of perspective and adhered to no scale of proportion in his architectural representations. His drawings of buildings are a curious combination of plan, section and elevation. We must conceive of a building being opened out flat so that side and front appear side by side. Considered thus his drawing of the tomb on the hillside is not without merit and is a most interesting parallel to the actual tombs now completely excavated. The only feature to be explained is the black top which he shows at the apex of his pyramid. In the debris of the Lower cemetery we found two small stone pyramidons with inscriptions, and in the Cairo Museum are quite a number of fine large specimens found in the Theban cemetery. We may now safely identify these as capping stones of the mud brick pyramids.

Image Number: 32497

The next tomb, No. 283, belonged to a man called Roy or Remy, the name being spelled both ways on a small granite statue of him found in the debris of the court. He was a Prophet of Amon and his wife was Ta-mut, a singer in the temple of Anion at Karnak. The plan of the tomb was similar to that of its neighbour but clearly was of later date than either No. 282 or No. 35 to the east. The axis of the tomb was askew and the whole plan was squeezed in between the two other tombs. Its tomb passage tunnel broke into the chapel of No. 282 and its pyramid overlapped and partly destroyed that of the latter. The court was surrounded with a colonnade of round columns, of which the bases of one or more remained on three of the sides. Owing to the offering room being cut too far out on the slope of the hill where the conglomerate stratum was particularly poor, the entire chamber had to be faced with masonry like that in the court in order to strengthen it. Even with this the entire ceiling had at some time collapsed under the weight of a gigantic boulder which almost blocked up the entrance to the corridor. As in the previous tomb the outline of the entire inner casing could be traced on the pavement. I have already mentioned that the tomb tunnel broke into that of No. 282. In cutting this the masons miscalculated their distance and started the tunnel at very nearly a right angle to the corridor at a point which they thought would clear the adjoining chapel. As soon as they broke into this, they changed the direction of their new tunnel and carried it down and around the chapel, but even in doing this they left the ceiling so thin that portions below the seated figures gave way and left small openings. This tomb was reused in the reign of Ramses IX (1140 B.C.) and considerably altered. The old tunnel and burial chamber were abandoned and a new tunnel was driven straight in on the main axis of the tomb. This started at the inner end of the corridor and sloped steeply down under the old statue niche which it partly destroyed, into a regular chamber from which another roughly cut room opened. At the same time a second court was added to the front of the tomb, bringing it well out over the side of the gully. This made it impossible to have the entrance on the axis and a second pylon was built on the east side of the outer court just clearing the facade of the court wall of No. 35. A sloping roadway was constructed to the new entrance over the vaulted roof of a tomb on the lower terrace (No. 284).

Museum Object Number: 29-87-462

Image Number: 34927

Tomb No. 35 was planned on a much larger scale and the workmanship was of a higher quality. Its forecourt was rectangular but much longer from east to west than it was wide, and was surrounded by a colonnade with square pillars instead of columns. The owner, Bekenkhonsu was a very important personage, First Prophet of Amon while his wife Mersagret was Chief of the Harem of Amon during the reign of Merenptah (1220 B.C.). The outer offering room was somewhat better preserved than some of the other tombs. Especially the colored decoration surrounding the door to the corridor. In Christian times this had been smeared over with brown color on which a crude design in red had been painted. Beneath this many parts of the original pattern of offering scenes to Osiris could be seen.

During the Saitic period, about 600 B.C., a new tomb was made opening from the northeast corner of the court of No. 35. The eastern end of the latter was walled off for a court and a new pylon erected. The tomb belonged to Besenmut, who possessed a variety of interesting titles. Not only was he Great Royal Scribe, but he was a lord and prince, Chancellor of Lower Egypt, Unique Friend, a true Royal Acquaintance and the Ears of the king of Lower Egypt. The plan of this tomb differed entirely from those of the Ramesside group. Here three chambers opened one from the other along the main axis extending in under the hill. The outer chamber was the most important, as it contained four offering niches each with a beautiful colored relief on the top panel. As this was the Renaissance period, the style of these imitated the Old Empire reliefs very closely and the wording of the inscriptions recalled the offering texts of the earlier age. This tomb was well within the limestone stratum and, with the exception of a wide fissure diagonally across the outer chamber was well preserved. The workmanship was excellent and the rooms were regular. The walls between the niches were divided into narrow vertical columns filled with inscriptions, light blue on a yellow ground. The ceiling was slightly curved and divided down the axis by bands of inscription into six panels, the three on one side of the axis corresponding to the three on the other. Each had its own unit of decoration, palmettes, circles, and interlacing squares. The door to the second chamber had projecting jambs and cornice covered with relief and inscriptions in color. This room and the inner one were so discolored by bats and smoke that no details of the decoration could be obtained, except here and there faint indications of blue characters on a yellow field. The burial chamber was reached through a square vertical shaft in the inner room. In the middle room was a curious feature. In the centre of the east wall was a well cut door with square jambs leading to a winding rock tunnel, which twisted downwards until it broke into one of the tombs on the lower terrace. The fine entrance proves it not to be merely a robbers’ tunnel.

The next tomb in the row was No. 158, situated higher up on the slope, and was built for Thenufer, a Chief Prophet of Amon during the XIXth Dynasty. It was only surpassed in size by No. 157 farther to the east, and it equaled it in the beauty of its craftsmanship, although unfortunately not so well preserved. The entrance pylon was built of solid stonework instead of brick, and had been faced with fine limestone as was also the pyramid above. The rock stratum at this point was of such very fine white limestone that the ornamentation was cut directly on it and not on a casing. Amongst the scenes was one of Thenufer playing draughts with his wife. On the jambs of the door into the main offering roof was a picture of paradise with the soul bird of Thenufer flitting about over a pool of water situated in the midst of date and fig trees. The statue niche at the eastern end of the chamber had been partly broken down by a later tomb cut, as in No. 35, from the northeast corner of the court. This had destroyed the figure of the owner leaving the seated statue of the wife and one of her little daughters standing by her side. The break had been repaired with well laid masonry but no attempt made to restore the missing figure.

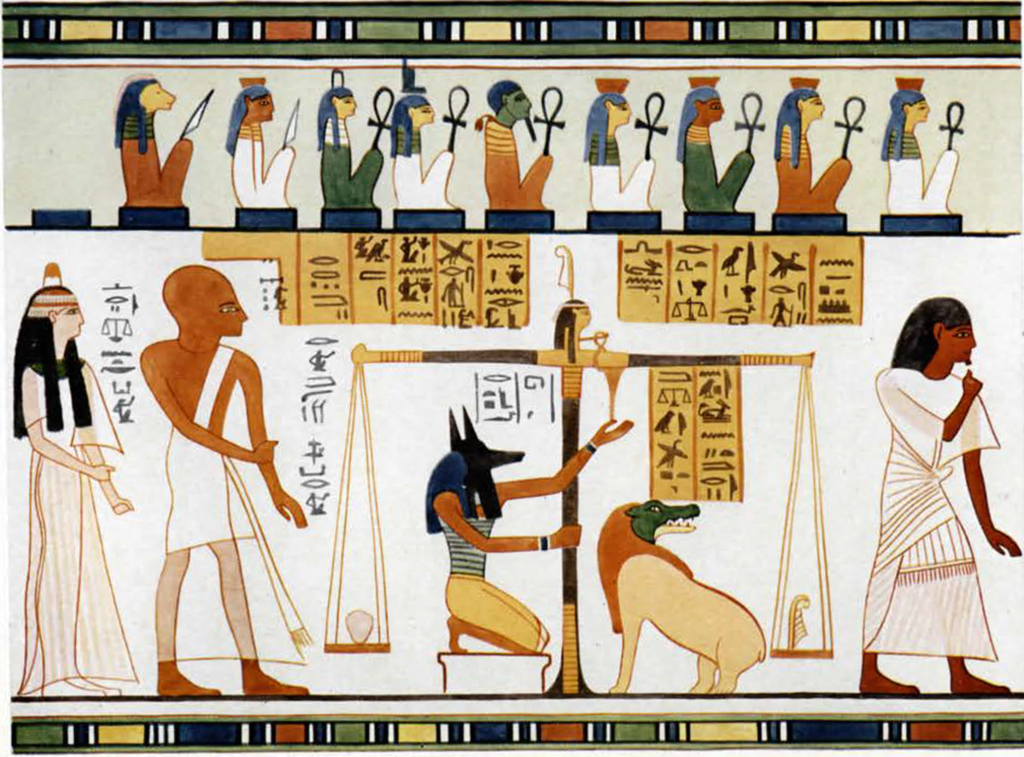

The tombs on the lower terrace were all much smaller and several of them apparently of earlier date than those on the upper row. The first at the west was No. 284 which was particularly interesting because of its reuse. Originally it consisted of a small square forecourt with entrance towards the south and a long transverse offering room with the inner chapel opening directly from it without the long corridor feature of the upper tombs. From the chapel a short tunnel wound down to the burial chamber. This tomb evidently preceded No. 35, as there had been a small window or opening in the rear wall of the court above the rock scarp which had been closed up by the filling in of the forecourt of No. 35. Later the court was divided by brick walls so as to form a T shaped offering room, with the transverse chamber at the south, all covered with barrel vaults. A new court was added at the south with its entrance at the east. The name of the original owner of this tomb was lost, as nearly the whole of the first decorated coat of stucco in the rock chambers was at some time badly burned and then largely stripped off before the new layer was put on. The second owner was one Pahomneter, a scribe and prophet of the divine offerings of all the gods in Thebes. Only one scene need be mentioned here and that is the one where Pahomneter in the judgment hall of the gods undergoes the weighing of his heart. He enters closely followed by his wife and stands in front of the great scales while Anubis observes the balance index to see whether the little figure on the deceased which here takes the place of the more usual emblem of the heart, in one pan, is outbalanced by the emblem of truth in the other pan. Thoth stands nearby recording the result while below a terrible composite beast awaits to devour the unfortunate man should he fail to pass the test. Farther on we see Pahomneter being led into the presence of Osiris, but here he is alone, his wife dropping out at this stage of the proceedings. A similar scene somewhat better drawn and preserved occurred in the tomb of Pasiur in the Lower cemetery.

Image Number: 32510

The other small tombs along the lower terrace require no special description. They belonged to lesser officials such as Ani, a store keeper of the goddess Mut; Niya’y, a scribe; Pandowe, a priest of Amon and Bekenkhons, a scribe of the divine book of Khonsu, and others. In a corner of a later house built against the pylon of No. 156 were found two jars filled with Demotic papyri, legal documents of one family of the time of the Ptolemies in the third century B.C. At the extreme eastern end was the largest and most important tomb of the whole area. This was No. 157, belonging to Nebunonef, first prophet of Amon, Divine father of Amon, chief of the prophets of all the gods of Thebes, overseer of the granary and treasury and a prince and lord in the reign of Ramses II. While adhering to the general plan of the Ramesside tombs it had been much amplified. The forecourt was buried under a mass of debris and built over by two Arab houses. The offering room was 86 feet long and 20 feet wide divided down the centre with a row of twelve pillars, each representing a shrouded figure of Osiris. All the walls were covered with colored reliefs. The corridor was enlarged into a hall 43 feet long and 22 feet wide, with twelve square piers in two rows. A small chapel at the inner end contained a niche for the seated statues which in this case were made in a separate piece and probably of some finer material. The tunnel to the tomb chamber was very well cut and very elaborate, and descended in steeply sloping passages following the sides of a square. At the bottom was first a long staircase ending in a small hall with eight piers. A second short sloping corridor led to the burial chamber which was cut and dressed very carefully. The pit for the sarcophagus was sunk below the floor and around the walls were ten small loculi for offerings. This tomb had the largest pyramid, set on a high pedestal around the top of which was the usual Egyptian cornice.

The Lower cemetery presented a most discouraging appearance. Everywhere over the surface were shallow pits marking the excavations made by tomb robbers, interspersed with the heaps of debris thrown out by them. In order to determine the contents of the area, a narrow strip was laid out extending from the temple at the edge of the fields along the eastern boundary of the concession towards the Upper cemetery. Within the set limits every square foot was examined and as the work progressed the earth was thrown back on the cleared portion, after the different tombs were measured and recorded. In all some eighty-six tombs were discovered and this gives a fair indication of the crowded condition of this portion of the necropolis. Nearly all the graves were of the simplest variety, a vaulted brick superstructure, a vertical shaft in the rock with a small rough chamber for the body at the bottom. The funeral equipment was slight and consisted for the most part of the ornaments of the deceased and some jars of food and drink. Several small stelae were found in the shafts probably fallen from their positions in the superstructures. These small tombs were built around and often inside the remains of larger tombs of the Middle Empire, which had been so often cleared out and reused that nothing of the original contents was left in situ. While clearing the rock forecourt of one such early tomb there came to light three other tombs of about the XXIIth dynasty, which had been cut in the rock scarp of the facade. These had only two chambers, the outer offering room and an inner chapel, but on the walls were abundant remains of fine ritualistic scenes.

Despite the fact that so much had been destroyed in former times, the excavation of the group of tombs at Thebes has proved of immense interest and importance. We now understand the arrangement and details of the tomb of a noble of the period and we can form a mental picture of the appearance of the necropolis as it must have appeared to the funeral processions as they wound across the fields on their way from the river. Against the warm red tones of the rocky cliff stood out in their white and gay colors, range upon range of massive structures, which with their lofty pylons and their colonnades resembled not so much tombs as the houses and temples of a great city. They formed a most impressive background to the sober colored mortuary temples of the Kings, which lay in a long line along the boundary between the cultivated fields and the vast desolate expanses of the cemetery, a rampart as it were between the living and their friends and relatives who had gone to reside in the city of the dead.

The colored plates accompanying this article have been prepared from full size drawings by Ahmed Effendi Kusuf, an Egyptian artist attached to the Expedition. They were copied for reproduction by Miss M. Louise Baker.