Vistors to the University Museum have noticed for some time past a group of three pottery statuettes in the Chinese section. The sturdy proportions of these figures and their vigour of modelling holds the attention, while the eye is delighted with the magnificence of the coloured glazes which they display. They are ornaments pure and simple, the work of craftsmen who could model with spirit if not always with great skill, and who knew the decorative value of the rich blue, purple, turquoise, and green glazes they handled. The deep violet blue which is the principal colour used on these figures reminds us of a Limoges enamel it glows with such depth and richness.

The two standing figures are companion pieces and represent two of the Eight Immortals of Taoist legend, Lan Ts’ai-ho and Lü Tung-pin. Lan Ts’ai-ho is the plump boyish looking one with his hair tied in two knobs like short horns and a girdle and shawl of leaves over his robe. He carries in his hand a basket of flowers which is the attribute by which he may be recognized. Flesh parts, face, hands and feet, are left in the biscuit, that is, the bare pottery, but the rest of the figure is covered with the rich coloured glazes mentioned, deep blue for the robes and brilliant turquoise for the accessories. Even the base which represents rocks is in the same colours. A touch of aubergine on the lotus flower in the basket is the only instance of the use of another colour. The statuette of Lü Tung-pin is fully as magnificent. He is represented as a man of considerable dignity, wearing a goatee and a high court headdress. Around his hips over his rich blue robe he wears a short skirt of turquoise which may represent armor. His attribute is a sword and this may be seen carried on his back over the left shoulder. Here again the face is left in the biscuit, but the hands are folded inside the turquoise sleeves of the inner robe and the feet are shod with well shaped court shoes. The garments of both figures flare out in a peculiar way at the bottom showing the turquoise lining and long turquoise trousers, and from the back of the pedestal a flat scroll form rises up to meet the hem of the robe and give added support to the figure. Doubtless these two once belonged to a complete set of the Eight Immortals.

The third statuette is that of a powerful man, some high dignitary or official, seated on a low oblong bench in the imposing attitude usually associated with the figures of Wen Ch’ang ti chün, the chief God of Literature. This important personage sits solidly with knees far apart and arms wrapped ‘in his mantle and folded in majestic mien worthy of an emperor. The head is set proudly on the shoulders. All faults in the modelling are lost sight of in the presence of such strength and vigour of handling as are shown here. As in the case of the other two figures the robes are of a glorious deep blue and details are carried out in turquoise. Here, however, the turquoise occasionally runs into a leaf green as brilliant and fresh as itself. Indeed the lighter portions of the headdress are entirely in this green. Warm ivory is another glaze not appearing on the other two figures. The ornaments in the front of the cap are of ivory and an ivory lining of the robe is revealed at the hands where the folds fall back across the knees. The face too is different. It has been heavily gilded and the gilt has tarnished giving an effect of polished bronze.

Image Number: 1615

This type of pottery figure was first made in China, so far as we can learn, in the fifteenth century, though its beginnings are to be found much earlier. It is not a development from the T’ang grave figurines as one might suppose but seems to have had quite a different origin. From the earliest times in China there had been tile factories in nearly every town and village, kilns which supplied the local demands for roof tiles and decorations. By the Ming period these tiles were nearly always glazed, the colours usually being green, blue, yellow, aubergine or white on a buff pottery body. Probably the most famous tiles are those from the “Porcelain Pagoda” at Nanking, a structure built between 1412 and 1431 and destroyed in. the T’ai-p’ing rebellion of 1853, and those from the Ming tombs near Nanking which date about the same time and were also destroyed in 1853. Tiles intended for roof finials and antefixal ornaments were often surmounted with decorative figures modelled skillfully in the clay. Ridge tiles carried the spirited forms of heroes, the Eight Immortals, other Taoist deities, men on horseback, dragons, phoenixes, and so forth. Modern collectors have sometimes detached these figures from their tiles and mounted them on stands, as may be seen in the case of a set of the Eight Immortals in the Kunstgewer-bemuseum in Frankfort (Illustrated in Schmidt, Chinesische Kera-mik, Pl. 89). Some have remained attached to the tile, as in the case of the little Bodhidharma of the Benson Collection (Illustrated in Hobson, Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, Vol. I, Pl. 58, No. 3). From such decorations for the exterior of palaces and temples it was but a step to make the separate figures to serve as ornaments for the interiors. Many were made on the same scale as the tile figures which were ordinarily ten to fifteen inches in height. The Eight Immortals of the Benson Collection are about fifteen inches high. But there are a number of well known examples that are considerably larger than the tile ornaments and that reveal a degree of skill in plastic art that one would hardly expect to find at a tile factory. Among the finest known are those in the Grandidier Collection at the Louvre which are about the same in size as the figures belonging to the University Museum. The Benson Collection, sold in 1924, was perhaps the richest in these figures. A standing Kuan-ti, thirty one inches high, was one of the finest and there were also two statuettes of Buddhist priests that were exceptional. In this technique also are several famous figures of Kuan Yin, among them a lovely one in the Eumorfopoulos Collection in London. Probably the largest example known of this class of pottery is the statue of a Judge of Hell in the British Museum. It is four feet six inches high.

Not all of these figures are of the same material or even covered with the same glazes as those in the University Museum. Indeed, being the product, probably, of various local factories throughout China it is surprising, rather, that there should be so much uniformity. Clays may be yellow, red, buff, or gray. Many of the works mentioned above show green and yellow glazes with aubergine, a sort of pinkish purple, making a colour triad that is very pleasing, but perhaps not as satisfying as the deep blue and turquoise colour scheme. The range of colour was limited by the nature of the glazes and the peculiar technique employed. This enamel on biscuit ware as it is called was produced by means of a different method from that which was being developed in the making of porcelain at Ching-tê Chen, the great ceramic center of China in the Ming period and later. There the porcelain body was made of a kind of clay called kaolin, or China earth, mixed with petuntse, China stone, which will become fusible only at a very high temperature. Colour or painted decoration was applied to the surface and the whole was dipped in a colourless glaze the chief ingredient of which was petuntse. Then the piece was put into a high temperature kiln and exposed to such intense heat that body and, glaze were fused into one homogeneous mass, hard, white, resonant, and translucent, a material which when broken showed no line of demarkation between body and glaze. These figures, on the other hand, and the tiles and other potteries related to them, had to receive two firings, one for the clay body and the other for the glazes. The ordinary tile clay was used for the modelling, in this case a heavy reddish buff. The bases were hollow and there was a hollow core going up into the figures designed for greater safety in firing. The process was as follows. The clay body was fired in the high temperature kiln and came out a heavy earthen- or stoneware which was said to be ” in the biscuit state,” which merely means the fired pottery before the glaze has been put on. The coloured glazes were then applied, usually with a brush, and the piece was fired a second time but this time in the cooler parts of the kiln since these glazes have much lead in them and could not stand a high temperature. It is for this reason that the French call them “couleurs de demi-grand feu.” It will be seen from observation of these three figures that when these glazes touch they tend to overlap and run into each other along the edge. This fact was probably what led to the employment of a peculiar technique in the case of a class of Ming potteries closely related to these figures. We refer to the class known as the cloisonné group. The University Museum has several examples of this type of pottery, large wine jars of strong and dignified form. One of them is of special interest to us not only because of its strong affiliations with these statuettes in regard to material and technique but also because there are depicted upon it the Eight Immortals with whom two of our figures are concerned. This jar is of heavy buff pottery. The designs upon it are outlined in raised threads of clay which contain the coloured glazes as the cloisins do the enamels in cloisonné. These clay threads serve as barriers and keep the glazes from running together. Here is the same biscuit body, the same deep blue and brilliant turquoise “couleurs de demi-grand feu” with the addition of yellow, green, and aubergine. Even the faces of the little figures are left in the biscuit. Can these also be by-products of the tile factories?

Image Number: 1613

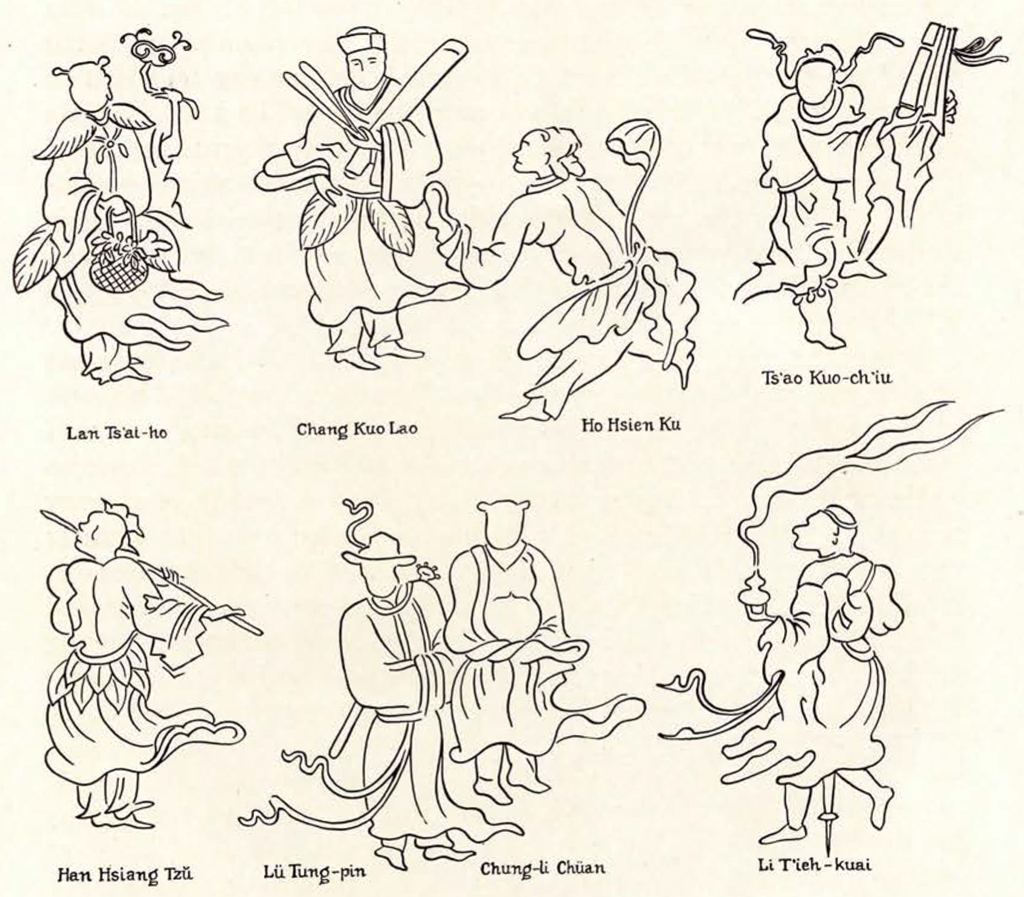

During the Ming period certain subjects for decoration were popular almost to the exclusion of all others. The subject of longevity especially fired the imaginations of the potters and inspired their art. The emblems of long life, the crane, the ling chih fungus, the pine tree, the peach of immortality, the long haired tortoise, and the spotted deer appear over and over again together with scenes depicting Shou Lao, God of Longevity, receiving court from the Eight Immortals in his mountain paradise or being congratulated by them. Sometimes the Immortals are seen crossing the sea on their way to visit Shou Lao, Wang Chih, the Chinese Rip Van Winkle, is represented watching the game of chess, or the scene shows the three Star Gods of Longevity, Rank, and Happiness seated around a checkers board. In view of the fact that two of the pottery figures we are studying belong to the Eight Immortals it may not be out of place to consider the whole set as depicted on the jar mentioned above. Most books on Chinese pottery and porcelain give a list of the Eight Immortals and their attributes but it will be found convenient as well as perhaps interesting to repeat various items here.

On one side of the jar are represented the three Star Gods sitting around a checkers board. To the right of them and proceeding around the jar in that direction we may distinguish the Eight Immortals as follows:

Lan Ts’ai-ho with a girdle and shawl of large leaves. He wears his hair in two knobs and carries his emblem, a basket of flowers, in his right hand. The left hand holds a ling chih fungus. (The left hand of our statuette is raised and pierced as if it also held such a fungus once.) Lan Ts’ai-ho is sometimes represented as a girl. A case of this may be seen in the painting numbered 29 in the Museum Collection where the slender graceful figure of a young woman with a basket of peony flowers makes a charming subject for an exquisite example of line rhythm.

Chang Kuo Lao was supposed to have lived in the early eighth century. He was renowned as a necromancer and had a magic white mule on which he traveled enormous distances and which he could fold up like a piece of paper and put in his pocket when not in use. He was once ordered to appear in court but refused to go. His emblem is a Taoist musical instrument consisting of a bamboo cylinder and two rods with which to play it. The rods are sometimes shown inside the cylinder. Chang was the patron of artists and calligraphers, a fact which supplies us with an interesting side light on the Chinese idea of the nature of the power possessed by painters and writers.

Ho Hsien Ku, who lived in the seventh century, was a girl who is said to have spent most of her time wandering alone in the hills. By eating of the powder of Mother of Pearl she obtained immortality and thereafter she rejected the food of mere mortals. That a being who would eat nothing but Mother of Pearl should be adopted as the patroness of housewives would seem most inappropriate. Certainly her mode of life was hardly such as would lend itself to imitation on the part of many housekeepers. Perhaps the point is, rather, that she would assist housewives to cook ” heavenly ” food. Her emblem is the lotus, usually in the seedpod stage, but occasionally she carries a spoon. She is shown here dancing gaily to the rhythm of T’sao’s castanets.

T’sao Kuo-ch’iu was the nephew of the Empress Tsao Hou and lived about the year 1000 A. D. He was therefore one of the last to join the band of the Eight. He is always dressed in court robes and wears an ancient court headdress with wings, or streamers. A pair of castanets was his symbol. He is the patron of actors. On this jar he may be seen dancing while he plays.

Han Hsiang-tzu, who was a pupil of Lü Tung-pin, was taken by his teacher to the Taoist paradise. There he climbed the peach tree of Immortality but had a fall from its branches. He is often represented wearing his hair in two knobs, like Lan Ts’ai-ho. His symbol is the flute and he is the patron of musicians.

Image Number: 1614

Lü Tung-pin, a most popular Immortal, was born in 755 A. D. It is said that while he was serving office as district magistrate he one day met Chung-li Ch’üan in the mountains and from him learned the secrets of alchemy and the mysteries of the elixir of Immortality. He was subjected to ten temptations, but overcoming them all was given a magic sword with which he slew dragons and other monsters throughout the empire. This performance continued for about four hundred years after which he disappeared. His emblem is the sword which he usually carries on his back. Probably the most famous representation of Lü Tung-pin is the magnificent ninth century painting which hung for many years in the Cernuschi Museum and is now on loan to the Metropolitan Museum. In it the human side of the worthy is emphasized, not his magic immortal self. Another painting which has also been in the Cernuschi Museum bears an inscription purporting to be a revelation obtained by Lü Tung-pin by the magic method of making the pencil descend, a sort of spiritualistic performance of the Chinese.

Chung-li Ch’üan is usually represented as a fat man holding a fan. He is one of the oldest of the Immortal Eight for he is said to have lived during the Chou dynasty. He is the Chinese philosopher who figures in the ironic story of the widow fanning her husband’s grave, so deliciously told by Hetherington in his Early Ceramic Wares in China. The sequel to the story is that Chung by his magic power assisted the lady in drying the sods on the grave and was rewarded with the present of the fan. Hence the emblem by which Chung is recognized.

Li T’ieh-kuai is perhaps the artists’ favorite Immortal. Legend states that Lao-tze himself used to summon him to the spirit world and there instruct him in Taoist lore. In order to go Li T’ieh-kuai had to leave his body, and it happened that once he returned to find that his body was gone. Luckily he came upon a lame beggar on the point of expiring by the roadside and thereupon entered the body which the beggar was vacating. After that he continued his existence in that form. His attributes are the beggar’s crutch and a pilgrim’s gourd out of which he can conjure clouds and apparitions, and when his spirit goes visiting it may be seen running along the stream of light which emanates from the gourd. He is the patron of astrologers and magicians.

Such was the merry band which in China held something of the same place that the nine muses did in Greece, and probably claimed far more of the popular favor. This worship of Longevity, of the great age of the body, inspired an art that was intensely expressive of itself. It led to a realism that seldom appears in Chinese art except under Taoist influence. There is in it none of that mystical spiritual feeling expressed by the Buddhist artists in their works, none of the matter of fact dignity and pride in respectability seen in paintings made under Confucian patronage. Rather is there a quaint gnome quality that is akin to the folk lore of northern Europe. Wizards, dwarfs, little old men of the hills with long beards and matted hair, witches and half witted boys with old faces, these were the subjects that kindled the fancy and led to an emphasis of the physical indications of age, bent or distorted forms, wrinkled old faces, a wild and unkempt appearance. Even in these pottery statuettes there is a touch of the physically uncanny.

It is true that neither in technique nor in subject matter are the figures in the University Museum unusual. The seated figure very probably does represent Wen Ch’ang ti chün and as such was another favorite subject of the Ming potters. But in respect to their size and beauty these figures are rather exceptional. In this they may be compared to the famous examples in the Grandidier Collection already mentioned. There is in that collection a Lan Ts’ai-ho extremely like this one. The head is larger, the basket is held on the arm, and the position of the hands is different, but the garments are identical and treated in the same manner and with the same pecularities of modelling as if the same hand were responsible for both. Close affinities exist also between the seated figure and a fine group in the Grandidier Collection representing a person of rank mounting a horse which is held by a groom.

The art of the Chinese potter has put him in the first rank among the craftsmen of the world. Some of his products are classed with the most beautiful works of art known. How shall we regard these by-products of his, these figures of his fancy whose forms he fashioned with but little knowledge, but into which he breathed a spirit that was full of life? All of these figures reveal grave anatomical defects when studied. The lifelike expressions of the Lan Ts’ai-ho and the Lü Tung-pin are due to the treatment of the eyeball and to the open mouth rather than to any understanding of the structure of a face. In the case of the seated figure the proportions of the body are incorrect from the waist down. It is a triumph of the artist’s spirit that such defects of construction should pass almost unobserved in the presence of the splendid sincerity and strength of the work. The biscuit parts of the two standing figures have been covered with a thin white slip, or coating of fine clay, and then painted to represent flesh, a colour now turned a dull yellowish brown. Black paint is used for pupils of eyes and for Lü Tung-pin’s goatee and mustache.

The rich colours of the glazes must be seen to be appreciated. The blue has great depth and richness and shows a high enamel like lustre where it is thick. Only here and there has it crackled at all. The turquoise is very brilliant and displays a fine even crackle, as does the ivory of the seated figure. The green is as smooth as jade and shows no crackle at all. An interesting feature is the gilding of the face in the one example. Gilding was frequently practiced in Ming times and involved an extra firing. It was done last after the figure was otherwise finished. Gold was put on in the form of gold leaf or the gilt applied with a brush (the latter method was probably the one employed in this case) and the gilt was then fixed by exposing the figure to the heat of the muffle stove, a low temperature kiln. It is therefore interesting to note that this seated figure has been given three firings in all, the first very hot, the second medium, and the third comparatively cool. Such gilding increased the richness of the work without making it gaudy, for ordinarily only the face was so treated. As a rule Chinese pottery shows a fine sense of colour proportion and harmony with one colour decidedly predominating.

Thus it may be seen that while these three figures are tremendously interesting as examples of a certain type of Ming pottery, and quite intriguing from the standpoint of subject, it is upon their artistic merits that we judge them worthy to hold a place in this collection. Applying here the same standards that we should apply to examples of mediaeval craftsmanship in Europe we find many characteristics analogous to those seen in Gothic wood carvings, thirteenth century stained glass, or fourteenth century enamels, a fine feeling for design in line, strength rather than delicacy, significance of attitude, and rich glowing’ harmonious colour. All these we have in these Chinese figures which are so nearly contemporary.