It is a well-known fact that wampum, or shell money, was in general use throughout the Atlantic coast in very early historic times and it is quite probable that the American Indians employed it as a true medium of exchange in a manner corresponding to our use of money even before the advent of Europeans. These shell beads may have become such a medium through their use as ornaments in regions distant from their place of manufacture. They were prized everywhere as ornaments and as such their value would become standardized. The basis for the establishment of a standard was the difficulty in shaping and perforating the beads. There was no possibility of destroying the standard of value by over production.

Museum Object Number: NA9143

Image Number: 12971

Wampum was made from several kinds of shells found along the Atlantic coast but the quahog, or common hard shall clam, and the periwinkle were in most favor. Great patience and considerable skill were required in the manufacture of the beads. On account of the intense hardness and brittleness of the shell the work of grinding and drilling was done by hand. Extreme care had to be exercised lest the bead should break from the heat generated by the friction of the drill. The hole was bored by holding the bead with the left hand against the end of the drill while the shaft was rolled on the thigh with the right hand. When the hole was half way through the bead was turned over and drilled from the other end. After drilling the beads were strung, ground to perfect cylindrical form, smoothed and polished. Anyone who wished to do so might make the beads, there was no monopoly. The English made an attempt to manufacture them by machinery but without success. Inferior ones were made by the whites and put into circulation but so much complaint was made by the Indians about these counterfeits that ordinances were passed to prevent their use.

Wampum was made in two colors; white, from the periwinkle, and purple, from the quahog. The value was determined by the color and finish. In New England, wampum so completely took the place of ordinary coin in the trade between whites and Indians that a value in shillings and pence was fixed by law. Connecticut received wampum for taxes in 1637 at the rate of four white or two purple beads for a penny. Three years later Massachusetts adopted the same standard of exchange and continued to use it well into the eighteenth century.

A very large proportion of the white beads especially were employed for personal adornment and for the embroidery of various articles of dress for both men and women.

Strings of wampum were used by the Indians for mneumonic records much as the Peruvians used the quipu of knotted cords. In making up the strings into belts it was possible by using all white, all purple, or by a combination of the two colors, to convey a variety of ideas, indicated by the sequence of the colors or the outlines portrayed. It was thus possible to express a number of ideas with clearness. The keeper of the wampum was thoroughly versed in the interpretation of the records and once a year he took the belts from their place in the treasure house to recite their significance to the public.

For use in ritual and ceremony, white was auspicious and indicated peace, health and good will, while on the contrary purple indicated sorrow, death and mourning. A string composed entirely of purple beads was sent by one tribe to the chief of a related tribe to notify him of the death of a chief. A white string tinged red was sent as a declaration of war. A purple belt, having a hatchet painted on it in red was sent with a roll of tobacco to a tribe as an invitation to join in war.

Belts were employed for official communications and for summoning councils. The selected delegates from other tribes presented belts as their credentials. At the opening of the council an address was made to the representatives from each tribe in turn and a belt given them which they preserved as a substitute for a written record. The following extract is from an address at the opening of a council held in the Muskingum Valley in 1764. (From Brice.) “Brothers, with this belt I open your ears that you may hear; I remove grief and sorrow from your hearts; I draw from your feet the thorns that pierced them on the way; I clean the seats of the council house, that you may sit at ease; I wash your head and body, that your spirits may be refreshed; I condole with you on the loss of the friends who have died since we last met; I wipe out any blood which may have been spilt between us.” With each expression a belt was presented.

Belts were used also for the ratification of treaties and the confirmation of alliances. The treaty belts were made of white beads with appropriate figures or designs in purple. The familiar belt which the Lenape Indians gave to William Penn is white with figures of two men in purple standing in the middle of the belt with clasped hands. When Washington was sent by the Governor of Virginia on a mission to the wilds of western Pennsylvania, he found that the French had made an alliance with the Indians and had given them a belt with four houses on it representing the four posts to be defended. Washington persuaded the Indians to withdraw from the alliance and they returned the belt to the French commander. Roads from one friendly tribe to another are generally marked by one or two rows of beads running through the middle of the belt from end to end. It means that they keep up friendly intercourse with each other.

In 1758 when Governor Denny sent Frederick C. Post to make a treaty with the Allegheny Indians he sent with him a large white belt with a figure of a man at each end and a streak of purple between them representing the road from the Ohio to Philadelphia. Post, adopting the Indian style of speech, said in presenting it, “Brethren of the Ohio, by this belt I make a road for you, and invite you to come to Philadelphia, to your first old council fire, which we rekindle again, and remove disputes, and renew the first old treaties of friendship. This is a clear and open road for you; therefore fear nothing and come to us with as many as can be of the Delawares, Shawnees or the Six Nations; we will be glad to see you; we desire all tribes and nations of Indians who are in alliance with you may come.”

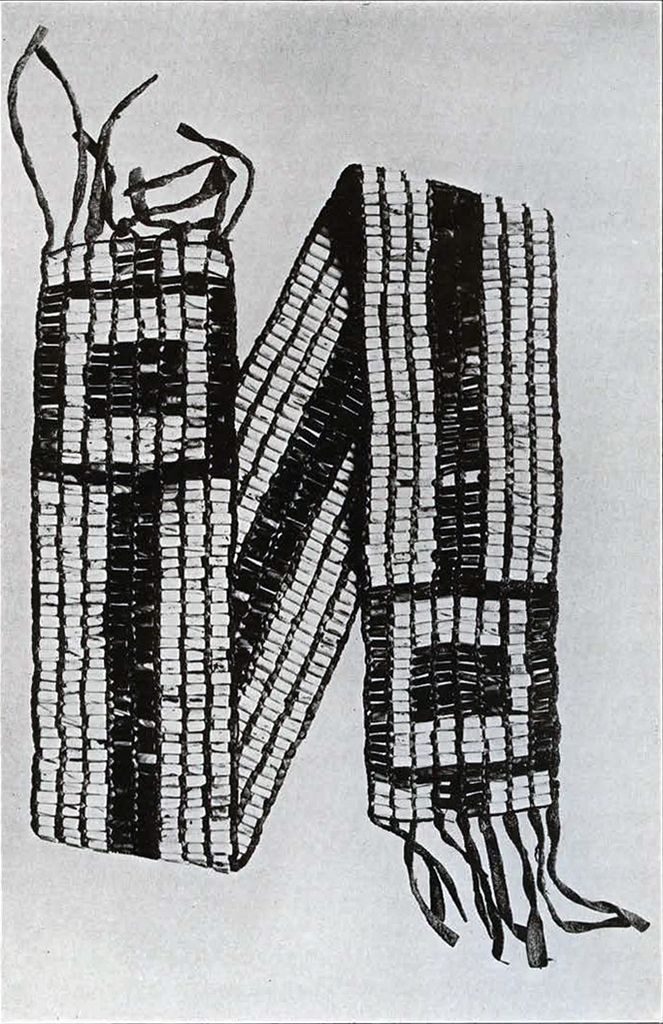

The belt here illustrated appears to be one of the type used in making treaties and in expressing friendly greetings. The squares, no doubt, are meant to represent two villages and the purple line the pathway between them. It is to be regretted that the exact history of this belt has been lost. The same regret may be expressed for the loss of the complete history of practically all wampum belts.

W.C.F.