FOR flights of pure fun and fancy there is no field of art more prolific than that of the Japanese netsuké. The recent gift to the MUSEUM of an extensive collection of these delightful small carvings in ivory and wood, and their exhibition in Pepper Hall, have been a source of keen enjoyment to many during the last few months. These netsuké, together with other small ivory carvings and one large one, were collected and donated by Mr. T. Broom Belfield, who has long been a member of the MUSEUM’s Board of Managers.

Netsuké were articles of use as well as of adornment. They developed in connection with the sagemono or hanging things that the Japanese of the last three centuries has worn suspended from his obi or sash, the tobacco pouch, the pipe case, and especially the little medicine case or inro. The netsuke (pronounced net’ski) was nothing but a button, or toggle, attached to the end of the cord from which hung the pouch, or the inro. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries especially, the netsuke was a common dress accessory, worn by merchant, samurai, artisan, and peasant. The poorer people could, presumably, afford only plain and unpretentious ones, but to supply the demand for more beautiful and amusing examples for the gentleman of means there arose gradually a distinct trade, a field of craftsmanship into which some very well-known artists were drawn. Many artists devoted their lives to the carving, inlaying, and painting of these small objects until the art of the netsuké carver attained a height unequalled, in the estimation of many, by any other class of ivory carvings in the world. For human interest, high technical skill, and originality, many of these delightful little objects surpass anything else akin to them.

Image Numbers: 4495, 4496

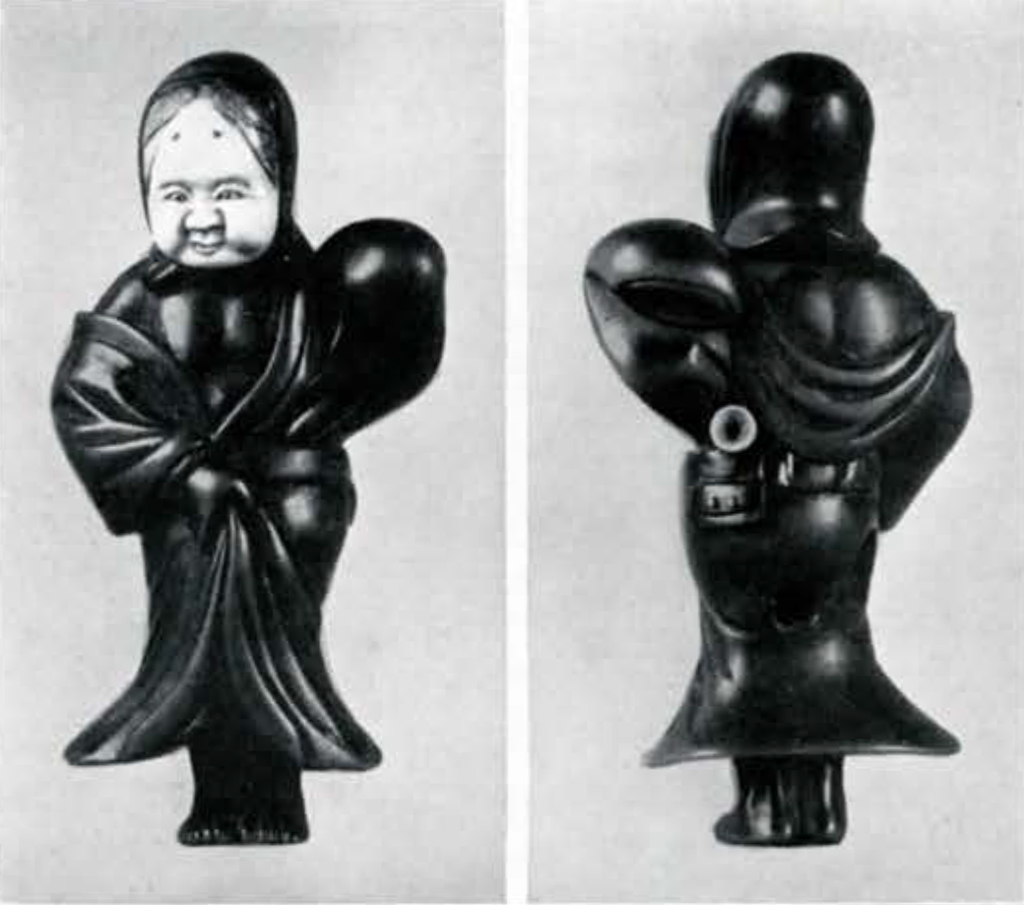

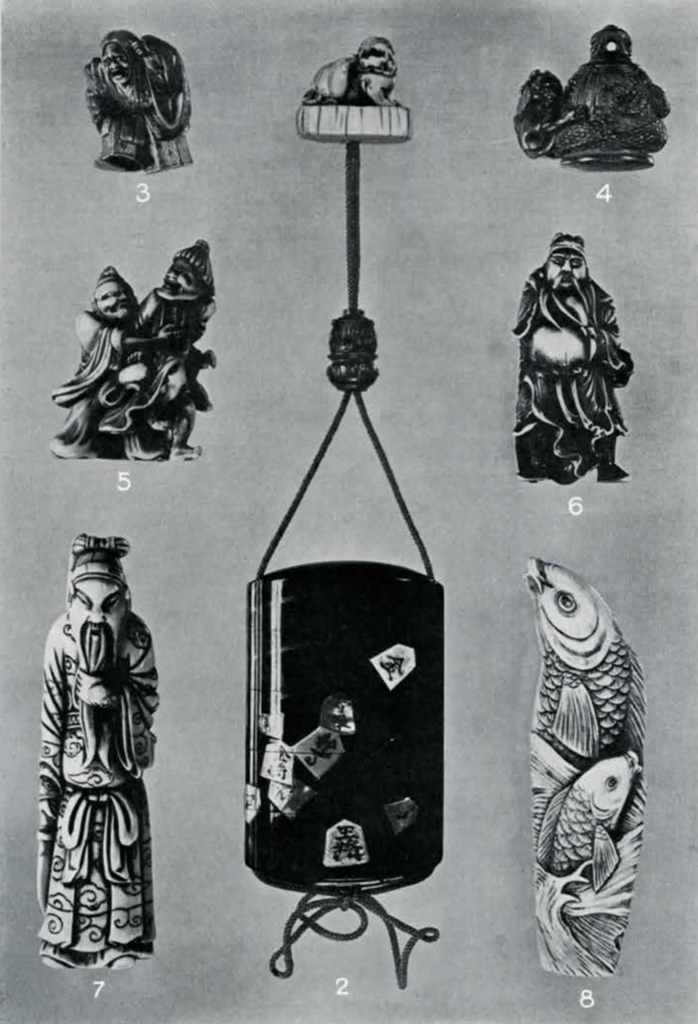

The method of wearing the netsuké may be seen from the illustration on page 262, which shows an inro with its cord and attachments. The two ends of a cord which serves to hold the compartments of the little case together, one end issuing from each side, were brought up to meet above the case, where they were run through a button, called an ojimé, which could be made to slide up or down on the cord, thus loosening or tightening the loop. Further up on the cord the two ends were passed through a hole in the netsuké and tied in a tight knot. When the inro was worn, the cord was tucked under the belt so that the inro hung below it and the netsuke above acted as a stop which prevented the cord from slipping down. Small inro of light weight could be held in place by small toggles; large heavy tobacco pouches might require large or long netsuké to anchor them firmly to the sash. The manner of wearing the inro is seen illustrated by one of the netsuke themselves. A charming piece in the Belfield Collection is the small girlish figure, carved in wood, of the chubby Uzume, goddess of mirth, standing wrapped in her kimono with a dainty pouch hung from her sash at the back. The hood is of very dark wood to contrast with the light-brown wood of the body, while the face is of ivory like the tiny round netsuke which holds the pouch in place.

Image Number: 2141

Netsuké were usually made of wood or ivory, but other materials were also used, such as bone, horn, pottery, porcelain, metal, lacquer, tortoiseshell, mother of pearl, coral, and stones of various kinds. Combinations of these materials were very skilfully devised, the most usual and pleasing being that of wood and ivory. Many of the best artists worked only in wood and, as might be expected, the simpler netsuke are generally the finest. The chief woods employed were cherry and box. Occasionally a black wood, possibly teak, was used. In the early nineteenth century there were some extremely clever artists who preferred ivory. We find them using the fine white grained variety of elephant ivory, the coarser walrus ivory, and the beautiful mellow so-called “fossil ivory.” Other small figures were carved also but a netsuke may be recognized by the marks of its use, the two connecting holes through which the cord was run. Occasionally one finds that an object not originally intended as a netsuke has been pierced with holes so that it may serve as one.

It is believed that the manju type of netsuké, the round flat button in figure 50, was the earliest, that the carving in the round of a small spherical button developed next, and that the more elongated figures, the masks, and such variations followed soon after. Certainly all types were in use together in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

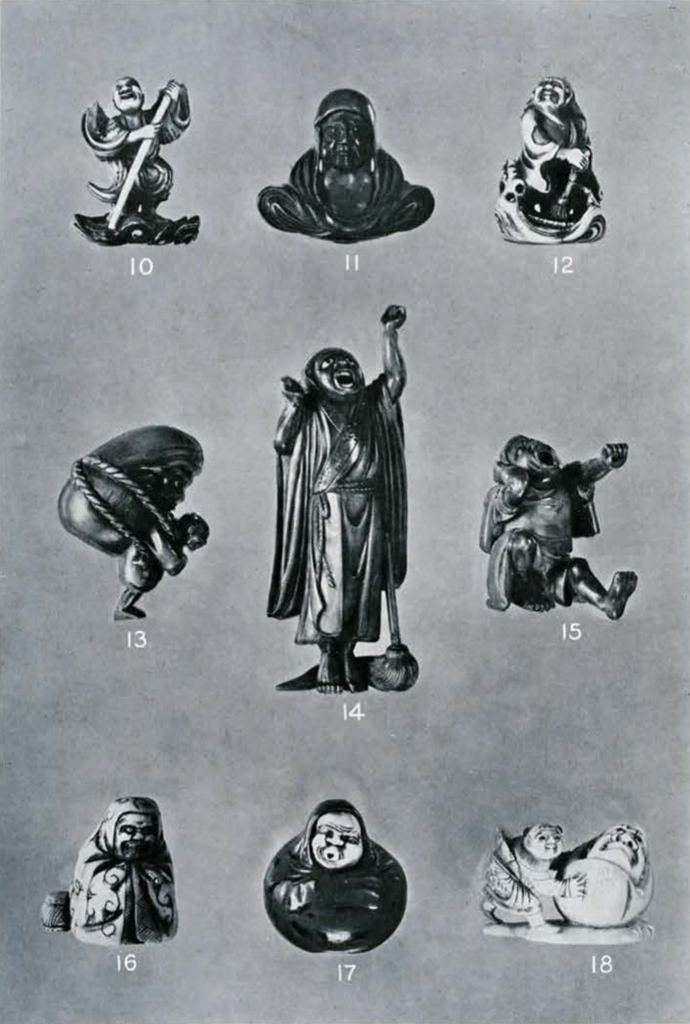

These small works of art fall naturally into groups according to their subject and it is intended to publish from time to time groups of the more interesting netsuke in the Belfield Collection, with the stories they illustrate or the subjects they represent. Since these carvings were made for the commoner as well as for the aristocrat, they cover a wide range of illustration and allusion. Legends and folklore supplied an enormous amount of material; historical subjects and heroes never fail; mythical peoples, gods and goddesses, historical personages and events, scenes and people of everyday life, animals real and imaginary, fishes and other creatures of the sea, illustrations of proverbs, little masks in imitation of those used in the No dances and other theatrical performances, figures of the dancers themselves, dragons, birds, fruit, and even the lowly vegetable, all are represented in a variety of ways, in various materials, and usually with a whimsical humour. Parodies abound. One rarely meets with actual caricature, but to poke fun of a good-natured kind was the order of the day and the amusing is depicted with unmistakable comic appreciation. One of the finest netsuke in the collection, for instance, is that here illustrated (figure 9). It represents a laughing man posturing as a crane by standing on one leg, hunching his back, and curving one arm high over his head to form the neck. The long fan is held so as to imitate the beak of the bird. The way in which the performer wraps his left leg around the other is shown in a most comical fashion. The wood is dark, highly polished, and delicious to the touch. It is a delightful piece. The signature reads Ryū-Kei. This artist lived in Yedo, apparently during the middle of the eighteenth century, and his work was highly praised by his countrymen.

Image Number: 2141

The netsuke carvers had respect for neither gods nor men. Especially do the venerable characters of religious history suffer at their hands. Bodhidharma, thr twenty-eighth Indian Buddhist patriarch, revered in Japan as Daruma, founder of the Zen sect of Buddhism, was often the butt of their jokes. The small seated figure shown on page 275, figure 11, represents him, it is true, much as he appears in the serious religious paintings of the time, but the smile is decidedly jovial and the earrings ridiculously prominent and incongruous, being made of ivory set into the dark wood. The netsuké is signed by Shū-min, an artist of the eighteenth century. The other netsuké of Daruma shown on the same page treat him with small reverence. According to Chinese records, Daruma arrived about 526 A.D. at the court of the Emperor Wu Ti in Nanking, then the capital of China. Having offended Wu Ti by failing to appreciate his good works, Daruma departed, crossed the Yang-tsze on a reed, and proceeded to Loyang, where he lived in the Shao-lin Temple. For nine years, it is said, he sat there in meditation, his face to the wall. This was a subject not to be resisted by the netsuké carver! Figures 14 and 15 represent Daruma enjoying a good yawn and stretch at the end of his nine years of inactivity, and it is evident from the expression on his face that the patriarch has found his joints rather stiff. Figure 16 shows him seated in meditation, wrapped in a brocade cloak. The face here is very typical, with its squarish shape and mouth drawn down at the corners. One of the jolliest netsuké of all is that of figure 17, a little Darurna in red lacquer and ivory. His body is entirely swathed in the red cloak, his ivory face screwed up humorously in a grimace. Figures 10 and 12 show him crossing the Yang-tsze, in the latter case on his own fly-whisk. And finally we see the lengths to which the netsuke carver would go illustrated in figures 13 and 18, for Daruma is there pictured as having lost his arms and legs through disuse and having become a sort of Humpty Dumpty who must be carried about and cared for by a priest. The priest in one group, the ivory netsuké, is rolling him along the ground and in the other, the wooden netsuké, has tied a rope around him and is carrying him on his back.

Image Number: 2133

Hotei, one of the Seven Gods of Luck, is a favourite with the netsuké makers and is always treated humorously. He was an enormously fat god, always laughing, and was much beloved by children. He carried a huge linen bag (from which he took his name, Ho-tei) full of the Takaramono, precious things, and he sometimes slept in this bag. Figure 20 on page 277 represents him as he most commonly appears, playing with a child. There is no mistaking the fat half-clothed body and laughing face. Even the ear lobes are huge and fleshy. He carries the child pick-a-back and holds a fan in his left hand. Figure 21 illustrates a very good netsuke of Ho-tei sitting in his bag, while figure 19 shows a most unusual and delightful one in which the bag of precious things is so large that the fat Ho-tei carrying it on his back is fairly dwarfed beneath it.

The figure with the exceedingly high bald cranium is Fukuro-kujiu, another of the Seven Gods of Luck. He is the Japanese counterpart of Shou Lao, the Chinese god of longevity, who seems to have had his origin in Lao-tzŭ, a sage of the sixth century B.C., the founder of Taoism. Because Fukurokujiu is the god of long life, he is represented as old and bearded. The mask netsuké, figure 26, illustrates the character of his countenance, one rather typical feature being the three lines between his eyebrows. He is usually accompanied by the symbols of longevity, such as the deer, the crane, and the tortoise. Figure 27 shows him riding a stag and figure 22 depicts him as a tortoise, or holding his cloak in such a way as to simulate the shell. Children are fascinated by his elongated skull, and many netsuke represent him playing with children who climb upon his huge bald pate or run along at his side, as in figure 25. He is shown in figure 24 stretching and yawning as if in imitation of Daruma. Most amusing of all, however, is the fine wooden netsuké pictured in figure 23 in which the god’s cranium is represented as so enormously high that the barber, who appears to be the god Daikoku in this case, must climb a ladder in order to shave its top.

Image Number: 2134

Shōki, the Demon-Queller, appears constantly among the netsuké subjects. Although he is properly a purely mythical being, he is connected traditionally with a historical personage, a student who lived in China during the early Tang Dynasty. Having failed in the Imperial examinations he committed suicide. When the Emperor heard of this, he gave orders that this student, Shiushi Shōki, should be buried with high honours. In gratitude for this Shōki’s spirit promised to spend its time forever in expelling demons from China. This story appealed tremendously to the carvers of netsuké, who depict Shōki as a fierce but rather impotent menace to the demon tribe. Dressed in armour and carrying a huge sword, he hunts demons and occasionally catches one, but is more frequently shown as the loser in the chase and the victim of their pranks. Figure 29 reproduces a fine ivory netsuke signed by Hidémasa. The scowling Demon-Queller has caught one small oni, or demon, by the hair and is fiercely looking around for the other, quite oblivious of the fact that that imp, grinning gleefully, is hiding on the top of his big hat. Shōki’s beard and the hair of the two oni are coloured black and details of the armour and embroidered cloak are beautifully engraved. Figure 31 shows Shōki being tormented by an oni which has climbed upon his back. One of the most amusing examples of the Shōki subject is that illustrated in the netsuké of figure 28. Here he has caught an oni and has tied him securely into a roll of matting which he carries on his back. With folded arms he stands listening to the oni’s cries of rage while an expression of complacent self-satisfaction announces: “I’ve disposed of him.” Again Shōki appears, foiled this time, in a delightful wooden netsuké, figure 30, where he peers down a well after an oni which has descended the well rope to escape. The little demon, incidentally, serves as the ojimé.

Image Numbers: 2135, 2144

The strange looking people who appear on the same page as the Shōki netsuké are Ashinaga and Tenaga. These mythical men were said to live in North China on the sea coast. The Ashinaga were long-legged men with very short arms while the Tenaga were very long-armed men with short legs. They lived upon fish which they hunted in pairs. The Tenaga caught the fish with his long arms while perched on the back of his long-legged companion who could, of course, wade far out into the sea. They are often shown catching an octopus, as in figures 32 and 34. Occasionally one is represented separately as in figure 33, which depicts an Ashinaga standing looking helpless and silly with the octopus held tightly it front of him. Ashinaga and Tenaga, shown together, often stood as a symbol of mutual helpfulness and coöperation.

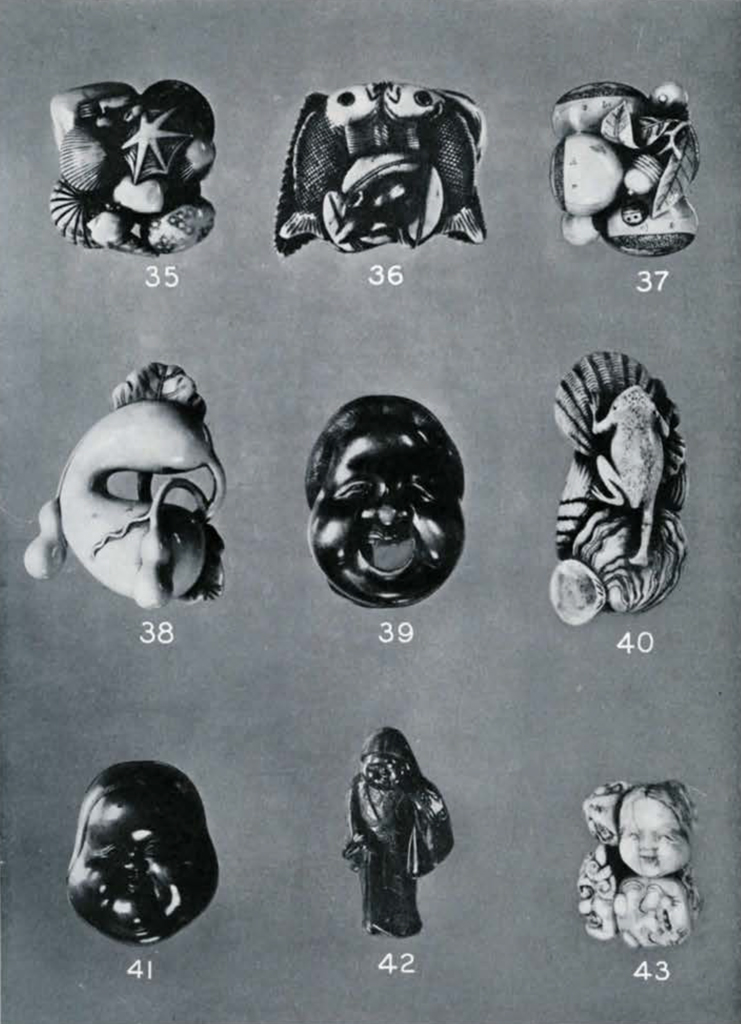

A little goddess of rank similar to that of the Seven Gods of Luck is the laughing Uzumé, goddess of mirth. The most delightful representation of her has already been described (figure 1) but the collection contains a number of other charming examples, for she was a favourite subject and often appears as a netsuke. Her narrow forehead with its two small ornamental spots (not always represented), her chubby puffed-out cheeks, and small smiling mouth make her easy to recognize. Figure 42 shows an adorable little Uzumé in red lacquer with a most exquisitely engraved embroidery design on her gown. Figure 41 is a wooden mask of her and 39 is another carved in darker wood and showing a slight variation from type in the arrangement of the hair, which is usually parted in the middle and drawn smoothly back on each side. She appears again in figure 43, a cluster of eight masks carved in ivory, and including a Kitsune (fox), Hiottoko, Obeshimi, two oni and others, Uzumé’s full name was Ama-no-Uzumé-no Mikoto and she is first mentioned in myth as one of the goddesses who helped to entice Amaterasu-ō-mi-kami, the sun goddess, out of the cave in which she had hidden, a story of early Japan which will be told in a future article.

Image Number: 2136, 2137

On page 273 may be seen two small netsuké illustrating the story of Kiyohimé. According to this legend, the holy monk Anchin was accustomed to stop at an inn at Masago whenever he came on pilgrimage to a certain shrine near by, and here he would play with the innkeeper’s little daughter Kiyohimé, pet her, and bring her small presents from time to time, never dreaming that he was encouraging something more than affection. But as she grew older Kiyohimé’s childish love for the priest became a fiery passion which burned more fiercely with every rejection of its proffers until it turned into a mad hatred. In desperation, finally, the monk fled into the temple, the girl in hot pursuit, and hid under the huge bell, ten feet high, which hung there. Kiyohimé, beside herself with rage, dashed wildly towards him. As she approached the bell, the framework supporting it gave way and it dropped down over the priest, imprisoning him beneath it. Foiled, the madwoman flung herself upon the bell, and as she did so her figure began to change, her face became that of an ugly witch, her body turned into that of a scaly dragon. Writhing furiously about the bell she struck it again and again while flames burst out from all parts of her body. Beneath the terrific heat the great bell became red hot and finally melted, Kiyohimé and Anchin both perishing in the molten mass of metal while, praying vainly, the horrified priests of the temple stood helpless by. A little handful of white ashes was all that was left of the priest, and of Kiyohimé there was not a trace. This legend was made into a Nō play called Do-jo-ji and the story became quite popular. Figure 3 shows a fine netsuké of Kiyohimé in a rage. It is made of wood lacquered and gilded; the hair is bright red, and the face, hands, and feet are of ivory. Kiyohimé coiled about the bell is the theme of figure 4.

Image Numbers: 2138, 2144

Kuan Yü, the Chinese god of war, is the subject of a number of netsuké. He is shown in figures 6 and 7, dressed in Chinese costume, holding his long beard with the left hand while his right grasps a terrible halberd. In figure 6, which is of “fossil ivory,” he wears armour in combination with his robes. Kuan Yū was an actual historical personage, a seller of bean curd in the time of the Three Kingdoms. In 184 A.D. he fell in with Liu Pei, a man of royal descent and of the military profession, and with Chang Fei, a blue-eyed, red-haired butcher who owned a garden. It was there that the three swore the famous “peach garden oath” of fast friendship, that they would share the same fortune and fight, live, and die together. The exciting adventures of the trio are well known in Chinese history. Liu Pei finally became master of Ssŭchuan and ruler of the Minor Han Kingdom (221-223 A.D.). Kuan Yū was one of his most powerful generals, a man famed for his prodigious feats of bravery and strength. He was renowned also for his faithfulness to his friend. One of the best known stories about him concerns his actions at the time he was captured by Ts’ao Ts’ao. The Ladies Kan and Mi, two of the wives of Liu Pei, were also among the prisoners and all were sent off to Ts’ao’s capital together. While on the journey Ts’ao, to test Kuan Yū’s fidelity to Liu Pei, assigned his three most important captives to the same bedchamber. But Kuan Yū foiled the tempter by standing all night at the door of the room holding a lighted candle in one hand and his drawn sword in the other, as guard and protector to the sleeping ladies. Ts’ao Ts’ao admired him greatly and would have had him join his own ranks, but Kuan Yū remained faithful to his old friend and returned to Liu Pei as soon as he was released. As Liu Pei’s general, he was his right hand in all the battles and campaigns by which he made secure his position as Emperor of Shu. Kuan Yū was at last captured and put to death by Sun Ch’üan, a rebel brother-in-law of Liu Pei. He was the most celebrated of China’s military heroes and was canonized as an immortal in 1128 and raised to the rank of Wang, Prince. In 1594 he was deified as the god of war, Kuan Ti.

Image Number: 2139

Another very fine netsuké is that illustrated on page 273, figure 5. The subject is Tadamori and the Oil Thief. Tadamori lived in Japan in the middle of the twelfth century and was the founder of the great Taira clan. At the time of the incident related in this story he was a young officer in the Imperial Guards. One of his duties was to accompany the Emperor Shira-Kawa-Hono on his visits to his concubine, the beautiful lady Gion Niogio who lived on the other side of the Gion Temple in Kyoto. To reach her house they had to pass through a grove of trees on the south side of the temple. One dark night in May when the rain was falling in torrents the Emperor with his young protector at his side was going by this grove when a strange apparition came stealing in and out among the trees. It seemed to have bristling hair standing out all over its head like shining wire, its face was scarlet, and light issued at intervals from its head. Much alarmed at the sight of such a monster, the Emperor paused while Tadamori went bravely forward to inspect it. As the strange ghostly thing passed him in the gloom and rain Tadamori sprang upon it desperately. To his surprise it offered little resistance and was soon overpowered. And no wonder, for it was neither ghost nor monster, but a poor temple servant going the rounds of the lanterns in the temple grounds to replenish the oil in them. The dilapidated straw of his rain hat and rain coat had made the impression of bushy hair, and the eerie flickering that had frightened the two travellers so much had been caused by the small torch he held in his hand and which flamed up whenever he blew upon it. One version of the story says that the servant was not replenishing the oil in the lanterns but stealing it from them, hence the term Oil Thief. The netsuké shows Tadamori bravely seizing what he took to be a goblin, while the wretched man, holding his vessel of stolen oil in his hand, laughs derisively.

A few of the netsuké depicting animals, fish, sea creatures, nuts, and vegetables, are shown here on pages 281 and 283. Figure 35 might be termed a “still life” group consisting of various shells: clam, listened to by mermaids; cowry, emblem of wealth; conch with a hermit crab in it; scallop; abaloné shell and sea urchin; two kinds of star fish ; and a common crab. Figure 37 is a cluster of chestnuts and acorns, the former being a symbol of success because of a play upon the meaning of the word for chestnut, kachiguri, in which kachi means success. A tiny ladybug on one of the chestnuts is realistically coloured red and brown. A large frog walks over the shells in figure 40. Figure 38 shows a big gourd, emblem of longevity. The netsuké pictured in figure 36 is rich in allegory, the pair of fish being a Chinese symbol for happiness through a play on the word fu, which means fish and also happiness. The fish are lying on some fern leaves, Japanese symbols of exuberant prosperity; a branch with peach leaves is folded over the edge, signifying long life, and the little mouse perched upon them all is a quaint fancy of the carver. Another good fish netsuké is that illustrated on page 273, where figure 8 represents carp leaping a waterfall, a common Japanese symbol of perseverance.

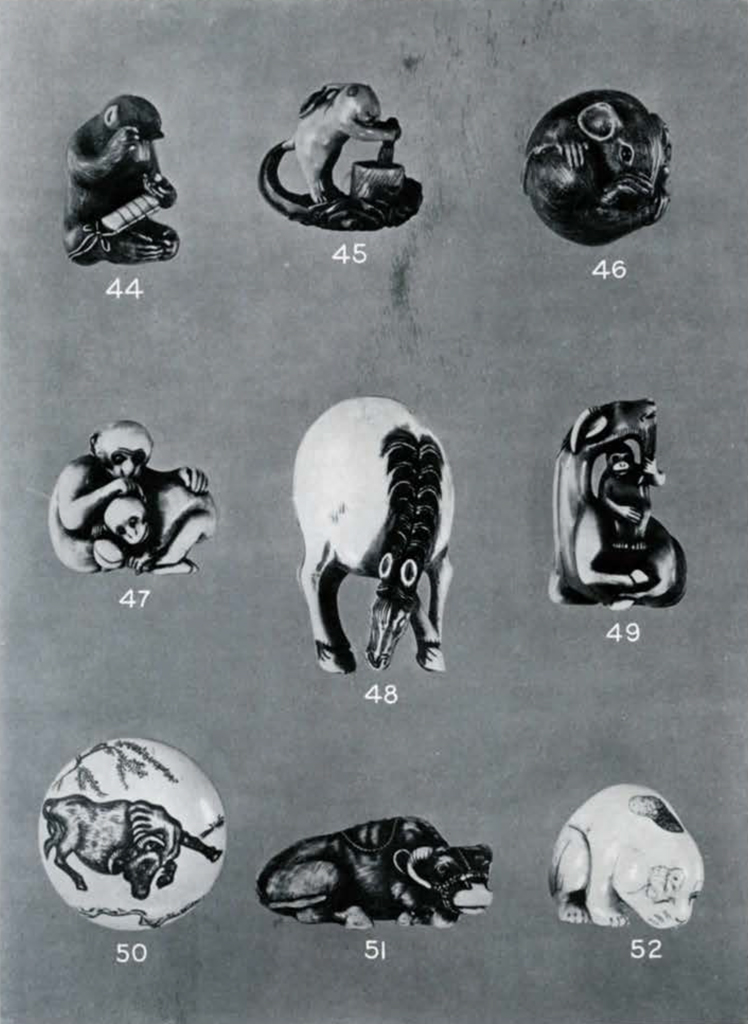

The subject of Japanese netsuké can hardly be mentioned without a word about the animals which are so beautifully represented. Many of them are the most realistic little carvings imaginable. Page 283 shows a group picked out more or less at random from among the dozens in the Belfield Collection. A number of the netsuké artists made a specialty of animals, just as was the case among painters of the same period. Indeed the carvers fell under the influence of the schools of naturalistic painting which flourished during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Shijo, Maruyama, and Ukiyo-yè, and just as the painter Sosen was famous for his pictures of deer and of monkeys, and Ganku for his tigers, so Ichi-kwan (or Ikkuan) was noted for his carvings of rats and Tomotada for his oxen netsuké. An exquisitely carved example by Tomotada is illustrated in figure 51, showing a buffalo lying down with halter and leading rope. The modelling is very fine and the hair delicately but richly indicated. Another is depicted on the button of figure 50, engraved in sunken relief, while the willow tree on the reverse is more lightly engraved. This netsuké is, however, signed by Hidémasa, another well-known carver. The horse of figure 48 shows a similar attempt at foreshortening and is a netsuké of very popular type, well suited for the use to which it was put. The ivory puppy netsuke, figure 52, is a very attractive example and has a fine mellowness and pleasing texture.

Monkeys were a favourite subject for netsuké and some of this class are extremely clever and amusing. Figure 44 is an ivory one in which the hair is very realistically engraved and coloured. It gives the impression of being of wood. The monkey is represented as examining through tortoiseshell spectacles—real tortoiseshell—a netsuké carved in the shape of a flower and attached to the cord of a large inro having five sections. It is signed Shō-min. Figure 47 is not so well carved but illustrates the typical humour of the netsuké carver. Figure 49 is an example of parody, the monkey sitting on the goat being intended to burlesque Fukurokujiu riding the stag. Figure 46 is one of Masanao’s rats, for which he was famous. The little creature is coiled up into a ball and looks so real that one almost expects it to uncurl and scamper away. Finally the hare of figure 45 must be noticed. This netsuké, of mellow old ivory, illustrates the legend of the hare in the moon, which is a very ancient Chinese symbol of long life. For the hare in the moon pounds the elixir of immortality in a mortar and here he may be seen standing on his hind legs with both front paws holding the pestle while he looks knowingly at you with his mild pink eyes of inlaid stone. Beneath his feet are cloud forms. This delightful little netsuké is signed Shigémasa.

Of the wealth of art and legend, history and everyday life represented in the Belfield Collection these few examples give but a slight idea. Among the six hundred and thirty-four carvings there are netsuké of almost every known type and subject, a veritable storehouse of material for the story-teller and the artist.

- Inro of lacquer inlaid with abalone shell and stones; 5 compartments.

Ojimé of metal: a shojo seated on its saké bowl holding the drinking bowl over its head.

Netsuké of ivory: a small Karashishi on a pedestal. - Kiyohimé in a rage: wood lacquered in red and gold; face, hands, and feet of ivory.

- Kiyohimé wrapped around the bell: wood. Signed, Min-kō (1735-1810).

- Tadamori and the oil thief : ivory.

- Kuan Yū standing with his sword: ivory.

- Kuan Yū: ivory.

- Carp leaping a waterfall : ivory.

- Daruma crossing the Yang-tsze: ivory, by Setsu-sai, 19th century.

- Daruma seated in meditation: wood, earrings of ivory. Signed, Shū-min, 18th century.

- Daruma crossing the Yang-tsze on his fly-whisk. Signed.

- Daruma carried by a priest: wood, by Minkoku.

- Daruma standing, yawning and stretching, with his fly-whisk at his feet: wood, eyes and teeth of ivory.

- Daruma seated, stretching and yawning: wood, robe painted red.

- Daruma seated, wrapped in his robe: ivory (by Ji-aki?).

- Daruma seated, wrapped in a red robe: lacquer and ivory.

- Daruma being rolled along by a priest : ivory, by Masahiro.

- Hotei carrying his bag: ivory.

- Hotei with a child on his shoulder: ivory, by Yoshi-tomo.

- Hotei sitting in his bag: ivory, by Kō-gioku.

- Fukurokujiu holding his cloak so as to simulate a tortoise: wood, by Shū-ichī.

- Fukurokujiu seated, with Daikoku as barber on a ladder shaving the top of his tall head: wood, by Hō-jitsu, middle of 19th century.

- Fukurokujiu yawning and stretching: wood, by Shū-getsu, middle of 19th century.

- Two children playing with Fukurokujiu: ivory.

- Mask of Fukurokujiu (or Shiwajo?) : wood.

- Fukurokujiu on the stag: ivory.

- Shōki, the Demon Queller, standing with folded arms; on his back an oni securely tied up in matting: ivory.

- Shōki holding one demon by the hair while another hides on top of his big hat: ivory, by Hidémasa, end of 18th century.

- Shōki, teased by an oni which has climbed on his back: ivory.

- Ashinaga and Tenaga catching an octopus: ivory, by Tomomasa.

- An Ashinaga holding an octopus: wood.

- Ashinaga and Tenaga catching an octopus: ivory.

- Group of shells, star-fish, and a crab: ivory, by Gyoku-hō-sai.

- Pair of fish, leaves, and a mouse: ivory.

- Chestnuts, acorns, and a lady-bug: ivory, by Gyoku-hō-sai.

- Large gourd on a vine: ivory.

- Mask of laughing Uzumé: wood.

- Frog on shells: ivory.

- Mask of Uzumé: wood.

- Uzumé: wood lacquered in red.

- Cluster of masks including one of Uzumé: ivory.

- Monkey examining a netsuké through tortoiseshell spectacles: ivory, by Shō-min.

- Hare pounding the elixir of immortality in a mortar: ivory, by Shige-masa.

- A rat: wood, by Masanao.

- Monkey picking lice from the head of her young one: ivory.

- Horse: ivory.

- Monkey on a goat in imitation of Fukurokujiu: ivory.

- Manju with engraving of a buffalo under a willow tree: ivory, signed Hidémasa.

- Buffalo reclining: ivory, by Tomo-tada.

- Puppy: ivory, by Kō-gyoku.