WHILE Cambyses led the Persian Army in Egypt, he was frightened by an obscure oracle at Buto, and sent back one of his officers to murder secretly his own brother Smerdis, whom he feared as a competitor. But who can avoid his destiny and escape the will of the gods? Another Smerdis was found, the mage Gaumata, who was placed at the head of the government in Suse while the king was at war. The secret murder served his purpose. None outside of Cambyses and his devoted officer suspected it. On the 11th of March, 522 B. c., in the fortress of Pishijâuwâdâ, in the mountains of Arakadrish, the mage boldly proclaimed himself the true Smerdis, son of Cyrus, thinking in his own mind: “They shall not know that I am not Smerdis” —la umassanu sha la Barzia anaku. He sent messengers to convey the good tidings all over the empire. Persia, Media, and the other provinces left Cambyses and followed him. He had cleverly exempted them of all taxes and military duty for three years.

Museum Object Number: B14543

Image Number: 7683

The news reached Cambyses while with his army at Ecbatane in Syria. He was not long finding out the artifice of the mage and decided to hurry on his way to Suse to unmask him. But in mounting his horse he wounded himself in the thigh with his scimitar and died within twenty days from an infection that followed. Before dying he entreated the noble Persians, in the name of the gods, protectors of the royalty, and specially the Achaemenides here present, not to suffer the empire to fall into the hands of the Medes.

After the death of Cambyses, Smerdis the mage reigned peacefully during the seven months remaining to finish the eighth year of the reign of his predecessor. Nobody among the Persians and the Medes dared seize the royal power from his hands. But finally the wit of a woman and the stern determination of seven noble Persians proved too much for him. The woman, Phedymy, daughter of the noble Otanes and wife of the late Cambyses, now a wife of the mage, ascertained during the night that the pseudo Smerdis had his ears cut, a sure sign that he was not the son of Cyrus, but the mage to whom this punishment had been inflicted in the past for some crime. Darius at the head of the conjurators did the rest.

“On the 10th Bâgajâdish—Sept. 29th 522 B. c.—I killed Gaumata the mage and his chief followers. There is a castle named Sikajauwatish in the country of Nisâja in Media. There I killed him and seized the royal power by the will of Ahuramazda.”

The killing of Gaumata was followed by a wholesale murdering of the mages. The day was called Magophonia after the murder, and was celebrated every year with great solemnity by the Persians. “I restored”—so speaks Darius—”the royalty that had been taken from our race and brought back everything as it was before. I built anew the temples which the mage Gaumata had destroyed.” The month of October 522—the month of dMarkazana, in the Elamite language—marked the beginning of the new order.

The details of this wonderful history have been preserved by the Greek Herodotus, and engraved in three languages and in cuneiform writings on the famous rock of Bisutûn or Behistun.

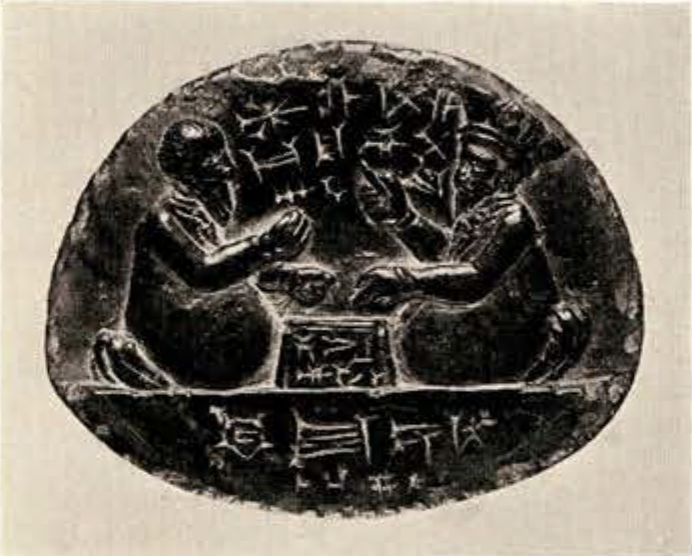

In the Maxwell Sommerville Collections in the University Museum, there is a Curious monument which has probably a close connection with the history of the triumph of Darius over Gaumata. It is a low relief on a beautiful piece of green jade stone, of almond form, measuring 49 1/2 x 40 mm., and 6 mm. thick, with tapering edges, as if to be set in the metal mounting of a ring or more likely of a crown.

The relief shows a scene of purely Persian inspiration. The king and his minister are squatted or kneeling on a platform, on either side of a square stone, a memorial. The king, distinguished from his minister by his crown, raises a finger on high in the natural attitude of an orator. He is the speaker in whatever dialogue is being exchanged between the two, for the extended hands of the minister also picture a lively conversation. Both have decidely Arian features, with high brows, straight noses and pointed beards. Both wear necklaces, perhaps bracelets, and long ceremonial robes.

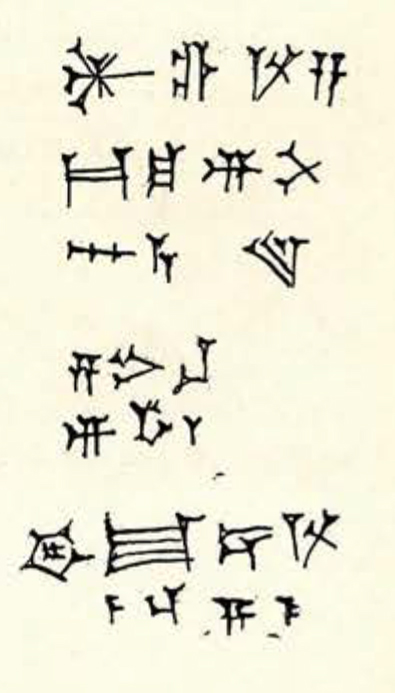

Seven lines of cuneiform inscription purport to make clear the meaning of the scene, or to record the words of the king in the memorable circumstance that caused the gem to be cut. The language used is probably the Babylonian, and several cuneiform signs or ideograms not found in the Elamite columns of Darius inscriptions, but purely Babylonian, make it almost certain. There is a certain clumsiness about the engraving, very different from the polished perfection of the relief. The inscription may be a later addition, scratched by an unsteady hand on the brittle surface of the jade stone. The text betrays an Elamite inspiration. It begins apparently with an invocation of the god dMar-gar-za, or dMar-sha-za, strangely akin to the god dMarkazana, the patron god of the month of October in the Elamite language, the month in which Darius restored the royalty and built anew the destroyed temples.

Three lines of inscriptions are above the hands of the king and seem to record his words. Two are on the square stone and probably identify it. The two last are on the platform below. The following is only a tentative translation of it.

Perhaps the stone cut by order of the king was preserved in the treasury of the temple of Susa, as a memorial of the triumph over the mage, and the restoration of the order in Persia at the hands of the Achemenides, in the month of Markazana. The temples were rebuilt, and the stone marked forever the overthrow of the false Barzia, the pseudo Smerdis.

CBS. 14543

| dmar-gar-za | Margarza |

|

| u-ma-si-nu(?zi) ina E-lam(?) |

has made known in Elam? |

|

| ZA amel Bar- zi(?)-a(?) |

stone of the Persians? (Smerdis?) |

|

| libbi kisalli ippuša ina Par-za-a(?) |

in the middle of the platform built in Persia? |