PEOPLE far and wide show an almost morbid interest in mummies. The word “mummy” immediately suggests Egypt and with justification, too, because the care which was lavished by the ancient Egyptians on their dead knows no parallel. There is undoubtedly a fascination in seeing bodies which have lasted for such a long time and in learning what these people actually did to preserve them.

Mummification, or the artificial preservation of the body, was practiced long before the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty (about 1580 B. C.), but at that time it became much more common and the art was well developed, reaching its peak in the Twenty-first Dynasty (about 1000 B. C.).

Museum Object Number: E16234

Image Number: 30996

When a person died, the body was escorted by sorrowing relatives and friends to the embalmers, where the latter displayed small models of coffins and explained the various methods by which they could mummify the body. According to Herodotus there were three ways, each varying in price, from the first, which was very expensive, to a third, which was quite cheap. Actual examination of the bodies has shown, however, that there were more than three ways. When the relatives had decided upon all the details, they went away, leaving the deceased in the hands of the undertakers, never again to see the face of the departed.

Let us suppose that in this particular case price meant nothing and the best of everything was desired. The brain was removed by means of an iron hook which was passed through the nostrils and ethmoid bone. It would probably be necessary to use other instruments in order to do a thorough job and after such an operation the nose would be much distorted. Next an incision was made in the left side of the body through which the hand might be passed to draw out the internal organs with the exception of the heart, which was never removed, and perhaps the kidneys. The viscera were cleansed, sweetened with spices, and placed in jars, the covers of which, until the Nineteenth Dynasty (about 1300 B. C.), were in the form of a human head. After this, the lids were in the form of the heads of the four “Children of Horus,” with whom the entrails were identified. In the Twenty-first Dynasty the viscera, after being cleansed, were wrapped in linen and restored to the body cavity, each with a small figure of its protecting genius.

In the second method mentioned by Herodotus the viscera were removed by the use of cedar oil, but if a man were very poor, the body was merely cleansed with a purgative.

The brain and body cavities were filled with linen and spices, among them myrrh and cassia. In the Twenty-first Dynasty the process of packing the body to restore it to its original form was very elaborate. The cheeks, neck, shoulders, arms, and legs were all stuffed. It is said that at the lips of the incision, the skin was separated from the muscle walls and stuffing was inserted to fill out the bust and the back.

To make certain that the nails would not be lost in the treatment to which the body was next subjected, they were often tied on with string.

Although it has been commonly thought that the body was next soaked in a solution of salt or of natron (common soda) in which it probably remained at least a month, latest research seems to show that there is no evidence for this belief. On the contrary there is evidence that the body was treated with dry natron as a dehydrating agent much as we now pickle fish. After the drying process the body was made ready for wrapping. In some rare cases the incision wound was sewed up but ordinarily a metal or wax plate, on which was depicted a sacred eye, was merely placed over the opening. The arms were either flexed at the elbow and crossed over the chest, extended over the lower part of the body, or placed at the sides.

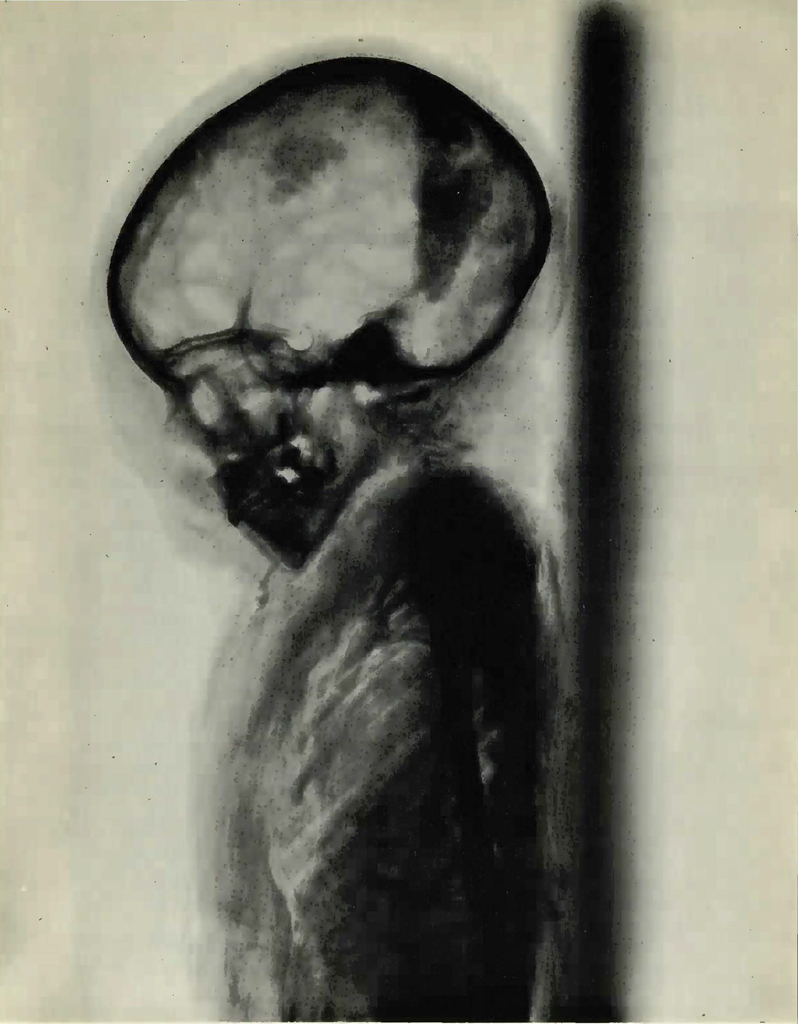

Undertakers cheated sometimes. Mummies with three legs and one arm and other absurdities have been disclosed by the X-Ray. The bodies evidently became dismembered and substitutions were made, all unknown to the relatives who viewed only the finished product.

The process of wrapping varied considerably. A few amulets might be placed on the neck, fastened there with string, to form a sort of collar. Linen soaked in resin was placed next to the body, to aid in keeping the air out, and upon this other amulets might be laid. A scarab inscribed with magical spells from the Book of the Dead was often placed on the chest, and other amulets on the arms, stomach, feet, and so forth. Between the legs was usually placed a roll of papyrus, inscribed, and illustrated in bright colors.

Next came, perhaps, an ordinary linen sheet, followed by a kind of long shirt, which was made in one piece and folded in the middle with openings, for the arms and head, the edges of which were hemmed. Upon another superimposed layer might be a network of very fine threads upon which would be a coarser sheet, perhaps with a painting of Osiris, the great god of the dead, wearing the atef crown and holding the crook and flail, with an inscription in hieroglyphs giving the name of the deceased.

Over all would be a large shroud of remarkably fine linen, along the edges of which were holes, a narrow band passing alternately from one side to the other and thus lacing up the covering on the under side of the corpse. Sometimes upon this were double bands of white and red linen; the latter, being narrower, were placed upon the white strips. One of these double bands ran lengthwise, while others were placed laterally across the body.

The deceased was now ready to be laid in a mummy-case or wooden coffin which might in turn be placed in one or more outer coffins, and if it could be afforded, in a final one of stone.

M. L. M.