Writing for the Museum Bulletin in December 1956 about our hopes and plans for the clearing, excavation, and consolidation of the vast Maya ruins of Tikal, I concluded with the observation, “If we succeed, Tikal will become a breathtaking experience for countless people, and it will teach them directly that a Stone Age technology and a hostile environment did not here prevent development of true civilization.”

Now, thirteen years later, the Museum turns over to the Guatemala Government complete responsibility for management of the Project, which we hope will continue under Guatemala leadership. But with William Coe and some forty scholars presently writing the reports of all these years of research to reach conclusions on the scientific results, it is the time to ask if we really have succeeded in what we planned in 1956.

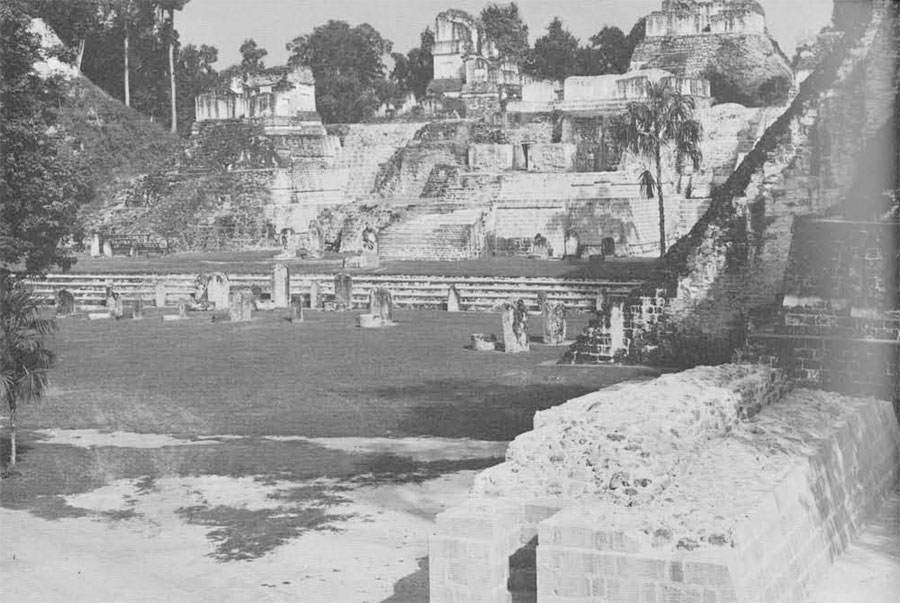

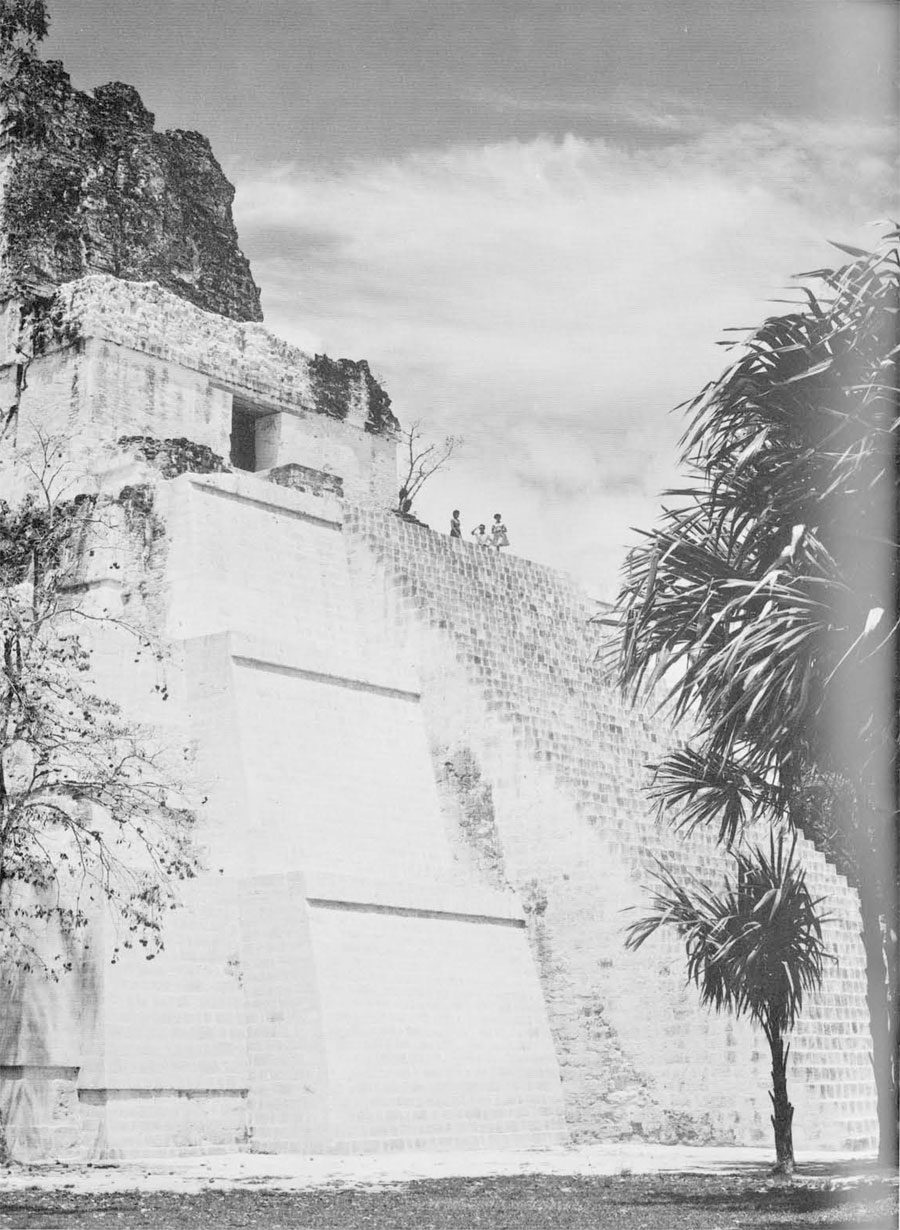

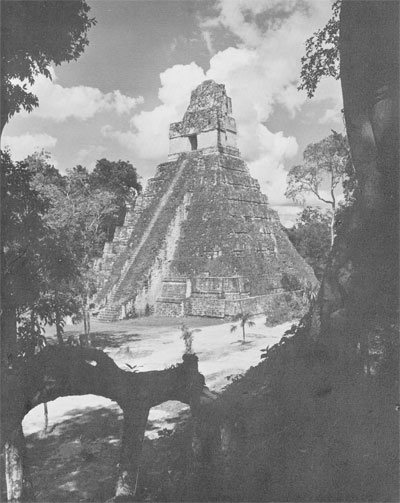

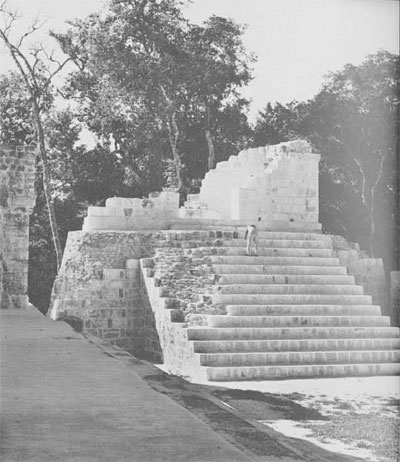

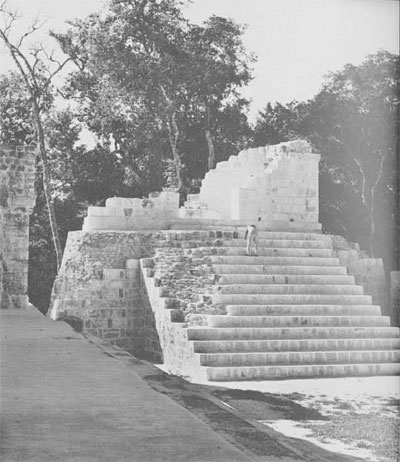

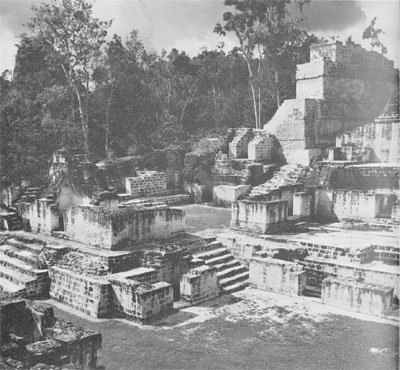

A few months ago, circling over the airfield and the ruins with Sam Carpenter in his light plane, all these years were suddenly telescoped as in a waking dream when a lifetime rushes past in a matter of seconds. There was first the dense jungle with two or three temple roof-combs flashing white images through the tree-tops and a tiny clearing with a few huts near the weedy airstrip. Then the bustle of Air Force planes unloading trucks, bulldozers, a sawmill, and a powerplant, with raw clearings creeping out through the forest. Then three settlements, that of the archaeologists with their bachelor workmen, that for the married workmen with a sawmill, school, and dispensary, and then a separate group of buildings to care for scores of tourists coming and going almost every day throughout the year. (Now we know that these separate clusters of buildings in some mysterious way follow the ancient building pattern of the Classic Maya.) Finally, as the last flash in the sequence of events, the brilliant white expanse of ruins around the great Central Plaza, so many of which have been cleared and preserved during the last five years. Surely this is a breathtaking sight for anyone who has flown for many miles over dense, forbidding, and uninhabited jungle. Everyone must ask, how did all this come about and what happened to it.

On the ground one first sees scores of limestone buildings, some soaring up to the height of a twenty-two story building, many sculptured stones with what must seem fantastic figures to the casual visitor, and a type of massive architecture completely strange to people with European traditions. In the museum at the end of the runway one sees two very puzzling things—stone tools so crude they look like those of very primitive people, but art objects in jade, bone, and pottery which are as sophisticated as those of the advanced civilizations of the ancient Near East—proof that grand art and civilization can be created with an almost Palaeolithic inventory of tools. The whole thing is a kind of paradox—the empty jungle surrounding a great stone-built urban center, a very crude set of working tools from our point of view, and at the same time elaborate artistic achievements in extremely hard materials like jade and obsidian and in well-fired and painted pottery. Even more startling is the elaborate system of writing seen on so many stone monuments.

Visiting Tikal, even the most casual and uninformed person, faced with such paradox, will ask many of those questions which archaeologists have been asking in the Maya field for more than a century. When and how did this all begin in Central America? Is it independent of Old World civilizations? How could such a city support itself in the dense jungle and in the shallow soil of the Peten? Why did it collapse?

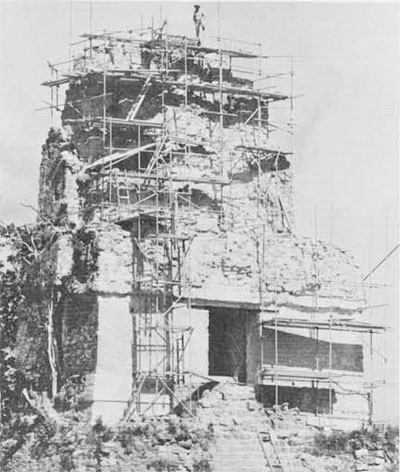

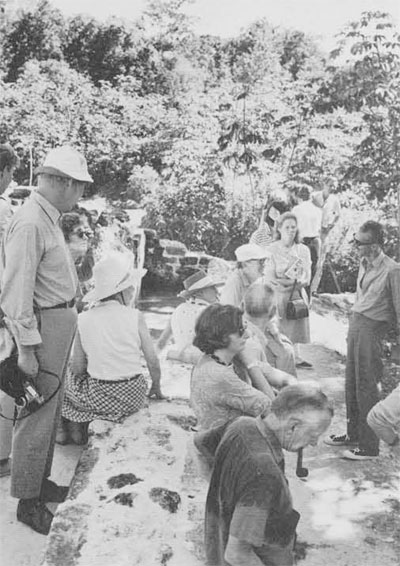

At the moment, when completing our Project, I am principally concerned with the effect of the Project upon people in general rather than with the archaeological conclusions now being reached by Professor Coe and his colleagues. A project which has cost well over one and a half million dollars and occupied scores of people over a period of fourteen years surely should be something significant to a great many people and not just to the professional academics involved in Maya research. On those many flights into Tikal with plane-loads of visitors, I have always noted, with pleasure, the quickening excitement as the plane circled the ruins and then the eager questions. What is it all about? Moreover, during these past years in the world press, in popular magazines, and on television and radio, a great many popular accounts of Tikal have circulated throughout all civilized nations so that the name of a Maya city and something of its meaning are known to many millions. Because of this, thousands every year will fly to Guatemala, circle over the ruins and ask all those questions of guides in the ruins and in the museum. I hope they will continue to see the surviving Maya Indians of today, our trained workmen, patiently and carefully clearing and preserving more of the hundreds of pyramids, temples, and palaces still lost among the dense jungle growth.

The simplest, and at the same time most difficult questions being asked by visitors quite certainly are not going to be answered in the volumes of reports now being prepared in the museum. Why did this strange civilization grow up in the lowland jungles of Guatemala and what really happened to it? At least we now know that Tikal was a going concern by 600 B.C. and that it continued until about A.D. 900. Therefter, Tikal, like all other Classic Maya settlements, ceased to be a living, growing city.

Somewhat ghostly survivors continued to live there for a few centuries robbing tombs and moving monuments about, perhaps to maintain in a pale way the ancient religious center, Just when it was totally abandoned to the jungle growth we do not know. That Tikal was a true urban settlement and not only a religious center is now clear. A great many simple dwellings, all over those six square miles which have been mapped and also some as much as seven miles from the Great Plaza, have been excavated. Segments of a combined wall and ditch which appear to be fortifications surround the large part of the area of ruins and indicate that the city may once have covered up to twenty-five square miles.

Basic facts about Tikal, such as these, are now being spelled out in both detailed and summary reports so that eventually both the Maya experts and the laymen will have a conception of what was probably the oldest and largest Maya urban center in America, at least insofar as contemporary archaeology can recreate it. But all these explanations and answers are not going to satisfy the intellectually curious person when he himself rediscovers Tikal in the jungle. And that is just as well, Surely it is all these unsolved mysteries about the nature of the world we live in which add excitement to learning and to personal experience when visiting a place like Tikal.

It is not possible here to thank all those persons who have made possible the Tikal of today, but I do wish to point out that the Project began as a gamble with about $20,000. supplied from each of two institutions, the University Museum and the American Philosophical Society. Thereafter, many private individuals like Mr, and Mrs. John Dimick, and many foundations like Avalon, Scaife, Rockefeller, National Science, and the Maya Foundation supplied hundreds of thousands of dollars. People who visited Tikal and who did not even know the University Museum often were so impressed that they sent contributions to us. In fact, there was a time when small contributions from scores of people kept us going. Then when the major financial supporters in North America had done their part the Guatemala Government took over the greater part of the expense for the next five years, with the staff of the University Museum directing the work.

The Guatemala Air Force and the national airline Aviateca, in fact, made the whole operation possible from the very beginning by supplying air transport which was for many years the only way of reaching Tikal. The Project has been an outstanding example of the best kind of international cooperation in the cultural field and has produced something of worldwide significance.