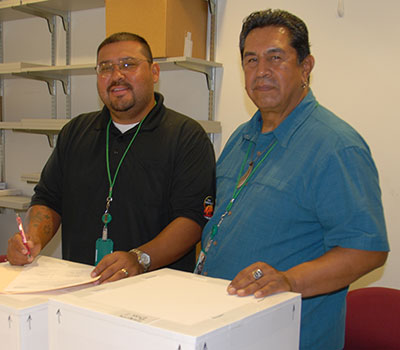

On November 2, 2015, Mr. Lalo Franco and Mr. Pete Alanis of the Tachi Yokut Tribe of the Santa Rosa Rancheria arrived in Philadelphia to receive ancestral human remains that had been part of the collection of the Penn Museum. This was a profoundly significant event for them as they took possession of the remains of their ancestors from the Central San Joaquin Valley for reburial back home in California. Mr. Franco shared the following story.

* * *

Several years ago the past Chairman of the Tachi Yokut Tribe, Mr. Clarence Atwell, Jr., traveled throughout his Yokut country reminding his relatives that with the passing of NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) we now can begin to heal from the wound that was inflicted upon us with the removal of our Ancestors from their graves, and that we must now make every effort to bring them home for reburial, and must unite to make this possible. He said that although we are no longer suffering a day-to-day existence we must never forget those Ancestors that have given us life.

As Franco and Alanis finished packing the remains in Philadelphia, they sprinkled tobacco inside each box and slowly recited a prayer and a song in their Yokuts language. Tobacco, they told us, grows at our peoples’ place of emergence in the San Joaquin. It will protect them and lead the way home. Once in California, Franco and Alanis reburied the remains in one of five tribal cemeteries on protected reservation lands, fulfilling their responsibility to the Creator.

These human remains were originally excavated in 1944 at Tranquillity, California by Malcolm Lloyd and Linton Satterthwaite, Jr., of the Penn Museum. Radiocarbon dating reveals the site was occupied in at least two separate stages between 6,000 and 1,500 years ago. Although the Museum determined there was not sufficient evidence to affiliate them with a specific present-day tribe, the human remains were excavated on aboriginal lands of the Yokuts, who are represented today by five federally recognized California tribes.

When NAGPRA was established by the federal government in 1990, it was estimated that between 100,000 and 200,000 Native American human remains were housed in American museums. After years of effort by Native American leaders, the law was passed as a human rights initiative to create a process for the repatriation of ancestral human remains and important cultural objects. Twenty-five years later NAGPRA has fundamentally changed the way American museums do business. Thousands of sets of human remains and cultural items have been repatriated to tribes across the nation. Yet while much has been accomplished, significant work still needs to be done to realize the goals of the law. The Penn Museum’s experience sheds light on these changes and ongoing challenges as it continues to reach out to tribes to determine their interest in its holdings.

How NAGPRA Works

NAGPRA provides a legal mechanism for the United States’ 568 federally recognized tribes, Alaskan Native Villages, and Native Hawaiian organizations to make claims for human remains and associated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony held by American museums and federal funding. For nearly two agencies that receive centuries, collectors and archaeologists removed human remains from unprotected American Indian graves for the purposes of scientific study. In some cases this was done in compliance with federal and state legislation and was necessitated to protect cultural resources when sites were inadvertently destroyed by natural or artificial means. Early collectors and anthropologists also amassed material culture from tribes they thought would soon be extinct.

The 1990 law requires museums to share information about how each set of human remains and each cultural object was acquired, to work with tribes who have an interest in these collections and may wish to make claims, and to publish federal notices before repatriations are finalized. The Penn Museum curates skeletal collections from around the world; within those collections are 900 individuals of Native American ancestry. Half come from Penn’s own archaeological excavations. The remainder include a modest collection on loan from the Wistar Institute of Philadelphia, the nation’s first (1892) independent biomedical research facility for whom the Museum manages the NAGPRA process, and the Samuel G. Morton Collection, a systematic 19th-century collection of human crania acquired by the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP) and transferred to Penn in 1997. Seventy thousand additional objects acquired from living communities are also subject to NAGPRA, but not all are eligible for repatriation.

Since its passage, the Penn Museum has worked rigorously to implement the law for the University. It created a NAGPRA Office and a Committee to help oversee the process and has mailed approximately 3,500 letters to federally recognized tribes informing them of our holdings and inviting consultation. The results are communicated to the public through the Museum’s NAGPRA website where each case is described and where links to the Federal Government’s public notices are made available.

To date, the Museum has received 46 formal repatriation claims. Twenty-seven returns have been completed, resulting in the transfer of 252 sets of human remains, 750 associated funerary objects, 14 unassociated funerary objects, 20 objects of cultural patrimony, 22 sacred objects, and 2 objects claimed as both cultural patrimony and sacred.

| Date | Native Group | HR(mni) | UFO | SO | OCP | SO/OCP | |

| 1990 | Zuni Pueblo | 15 | |||||

| 1991 | Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’I Nei | 1 | |||||

| 1994 | Chugach Alaska Corporation | 85+ | 703* | ||||

| 1996 | Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’I Nei | 62 | |||||

| 1997 | Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’I Nei | 8 | |||||

| 1998 | Cayuga Nation of New York | 2 | |||||

| 1998 | Oneida Nation of New York & Wisconsin | 2 | 4 | ||||

| 1999 | Winnebago of Nebraska | 2 | |||||

| 1999 | Hui Malama I Na Kupuna O Hawai’I Nei | 2 | |||||

| 2000 | Cayuga Nation of New York | 1 | |||||

| 2000 | Jamestown S’Klallam of Washington | 2 | |||||

| 2000 | Klamath Tribe of Oregon | 1 | |||||

| 2000 | Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma | 1 | |||||

| 2000 | Village of Unalakleet, Alaska | 1 | |||||

| 2000 | Chugach Alaska Corporation | 37 | 43* | 14* | |||

| 2002 | Organized Village of Grayling, Alaska | 19 | |||||

| 2002 | Native Village of Kotzebue, Alaska | 1 | |||||

| 2002 | Comanche Tribe of Oklahoma | 1 | |||||

| 2002 | White Mountain Apache, AZ | 1 | |||||

| 2003 | Miami Tribe of Oklahoma | 12 | |||||

| 2005 | Sac and Fox Tribe of Mississippi in Iowa | 1 | |||||

| 2006 | Sisseton Wapheton Oyate Tribe, South Dakota | 1 | |||||

| 2007 | Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma | 1 | |||||

| 2008 | Hui Mālama I Nā Kūpuna O Hawai’i Nei, the Hawai’i Island Burial Council, and the Office of Hawai’i Affairs jointly | 1 | |||||

| 2011 | Hoonah Indian Association, Huna Heritage Foundation, & Huna Totem Corporation, Alaska | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2013 | Cherokee Nation, OK, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, NC, and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, OK | 6 | |||||

| 2015 | Keweenaw Bay Indian Community | 1 | |||||

| 2015 | Seminole Tribe of Florida | 21 | |||||

| 2015 | Santa Rosa Indian Community | 5 |

*approximate number

HR(mni)=human remains (minimun number of individuals)

AFO=associated funerary objects

UFO=unassociated funerary objects

SO=sacred object

OCP=object of cultural patrimony

Prioritizing Human Remains

The majority of repatriation claims received by the Museum to date have requested human remains. Tribes are continuing to focus their repatriation efforts in this area so that their people can regain balance in healing the devastating effects of colonization on Native American cultural identity. Some tribes believe that ancestral sites and human remains, as physical embodiments of the past, are sources of ongoing power and knowledge and should not be disturbed. Others are developing new protocols to safely recover the remains of their ancestors. Many, like the Yokuts of California, have a moral duty to rebury the remains. In all cases, the return of ancestors to home communities requires thoughtful care, preparation, and resources.

A total of 252 human remains from the Museum’s collection have been repatriated to 16 different tribes, including 120 to the Chugach Alaska Corporation near Prince William Sound and Cook Inlet where Dr. Frederica De Laguna excavated in the 1930s, 74 from the Morton Collection to the Hui Malama I Na Kupuna ‘O Hawai’i Nei of Hawaii, and 21 from the Morton Collection to the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

The Museum’s NAGPRA Office has made every effort to share its documentation about its collections with tribes. However, its work is not done, and we continue to identify related papers in various archival institutions in Philadelphia and around the country. By working in consultation with tribes to carefully recover this documentation, it is the Museum’s hope that the archival records will shed light on the collections histories and provide evidence to more accurately identify which present-day tribes are affiliated with the human remains we steward.

A Cherokee Case Study

The 2013 repatriation of human remains to the Cherokee Indians serves as a good example, showing the timeline, the importance of the documentation, the process, and the mutually beneficial outcomes of consultation. Information about the Penn Museum’s Cherokee holdings was mailed to three Cherokee tribes in the early 1990s and again in 2001 after the transfer of the ANSP collections to Penn. In 2011, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina began discussions with us about repatriating the human remains. Their Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) gained confirmation from each related tribal organization in Oklahoma and, together, we finalized the required Federal Notice. In September, THPO officers James Griffin and Tyler Howe traveled to the Museum to receive the remains.

The tribe received six human remains from Morton’s collection of human crania obtained originally by medical and military doctors in 1838 and 1846. Some were children recovered from a cave context dating to the Historic Period when epidemics and forced removals resulted in many deaths. Another individual was described in 1846 as “one of the best ball players in his tribe who, while playing ball, slipped and fell and dislocated his spine and died immediately.” Stickball, similar to lacrosse, has been played for centuries by eastern tribes and, upon review, this skull exhibited trauma consistent with ball playing. Griffin and Howe shared oral history about one of the last ball games of 1845, when three players were killed and several injured. Once home, they sent photographs of 2013 stickball games for our use in teaching and invited us to Cherokee, NC to participate in their Annual Archaeology Days Seminar to encourage Cherokee youth to get involved in archaeology.

Culturally Unidentifiable Human Remains

A number of human remains are considered culturally unidentifiable (CUI) under NAGPRA. The legal process for the repatriation of human remains in this category was added to the law’s regulations in 2010. Unidentifiable human remains are those for which no shared group identity serves as a bridge of continuity from a past community to a present-day tribe. For example, lack of documentation may prohibit this link. In some instances only the state name where human remains were acquired is known. Moreover, the antiquity of some remains is a factor when there is not a clear understanding of the relationship between a past group and present-day tribes.

Before any repatriation can take place, it is the Museum’s obligation to consult with all federally recognized tribal entities that may be a afifliated with each set of human remains. Often we consult with several tribal entities. Remains from Michigan, for example, require input from 33 different tribes. If one tribe, or a consortium of tribes, wishes to take the lead on repatriating specific remains, the Museum seeks agreement from all affiliated parties.

NAGPRA recognizes that there may be instances where non-federally recognized groups may be appropriate claimants, and museums and federal agencies that wish to return human remains to these groups must make a request to the Secretary of the Department of the Interior. The Penn Museum is open to working with these groups should human remains in its collections be found to be associated with tribes presently not recognized by the federal government.

A California Case Study

In cases where human remains are determined to be Native American, but for which no lineal descendant or culturally affiliated present-day tribe is identified, the Museum consults with tribal entities who controlled the land the remains were removed from and with tribes recognized as aboriginal to that geographic location. Under NAGPRA, aboriginal occupation is recognized by a final judgment of the Indian Claims Commission or the United States Court of Claims, or by a treaty, Act of Congress, or Executive Order. Taking into account the numerous removals of tribes by the federal government and the movement and relocation of native communities through time, it is also possible that more than one tribe may be associated with a particular place.

In the case of human remains from Tranquillity, a relationship of shared group identity cannot be reasonably traced between the human remains and any present-day Indian tribe. Indian land cessions and the Treaty of Camp Keys (May 30, 1851) indicate the remains were removed from aboriginal lands of five federally recognized tribes. During consultation, the Tachi Yokut indicated their interest in seeing the remains reburied, one tribe supported their request, and three tribes did not respond. During consultation Mr. Franco reviewed other artifacts in the Museum from his community. In 2011, we informed the Tachi Yokut of a scientific testing proposal from a Smithsonian Institution scholar requesting radiometric dating of the human remains from Tranquillity. While not all tribes are open to scientific testing, Mr. Franco appreciated being informed of the proposal and was open to research questions that could share new information. The results of that study allowed for precise dating of the Tranquillity human remains.

Sacred Objects and Objects of Cultural Patrimony

Many tribes across the country are also actively repatriating sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony. As they are doing so, they are immersing their youth in tribal values and histories and strengthening their spiritual, religious, and cultural practices. According to NAGPRA’s legal definitions, sacred objects are needed by religious leaders for the ongoing practice of tribal religion. Objects of cultural patrimony hold ongoing, central significance for the entire community. To date, the Museum has returned 24 sacred objects and 22 objects of cultural patrimony. Eight were transferred to the Tlingit of Southeast Alaska.

A Tlingit Case Study

Louis Shotridge was a Tlingit Indian from Southeast Alaska who served as Assistant Curator at the Penn Mu- seum from 1912–1932. Trained in anthropological methods, Shotridge spent most of that time in the eld, studying his Tlingit communities and collecting for Penn. He purchased and carefully documented 500 Tlingit objects, which he wrote about and exhibited in Philadelphia. In 2011, the Museum created the Louis Shotridge Digital Archive to make these collections accessible online.

The Museum has hosted seven Tlingit NAGPRA consultation visits to discuss objects in the Shotridge collection. Two clan leaders, along with the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, have borrowed clan regalia for memorial potlatches or Koo.eex so they could be witnessed, danced, and appreciated by clan members according to Tlingit protocol. The Museum has made this a priority and the Raven of the Roof hat, Eagle hat, Petrel hat, Shark helmet, and Wolf hat have each travelled with their own seat assignments on airplanes. These objects were welcomed and danced by clan members, and later returned to Philadelphia. On these occasions, the Tlingit people welcomed Museum staff into their homes and treated us like family. Museum staff have also participated in educational clan conferences sharing information about Shotridge’s work. In the process, Tlingit communities have learned that their ancestor made significant contributions to the study and preservation of Tlingit history and culture. In 2006, several Tlingit clan members, visiting as part of a repatriation consultation, participated in a study of the genetic diversity of Haida and Tlingit populations. This provided new information about their tribal histories that was shared with those communities. In 2010, the Central Council of Indian Tribes of Alaska requested radiometric dating of three Tlingit clan hats in the collection; the results helped clarify their dates of manufacture and clan histories.

Two returns of objects in the Shotridge collection have been authorized by the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. In 2009, though the University held the right of possession to the objects, it agreed to return 8 of 45 objects claimed by the T’akdeintaan clan of Hoonah. One object, the Lituya Bay Robe (see page 28), was claimed as both a sacred object and an object of cultural patrimony. Named after a place of reverence on the landscape associated with the founding of the clan, the robe is of central importance and is needed for the continuance of clan religion. In recognition of the historical significance of the remaining objects, the University also proposed a joint curatorial and custodial arrangement to situate the 37 objects in Alaska, where they would be available to the clan.

In 2010, the University Trustees agreed to return clan objects and establish a partnership with the Tlingit Kaagwaantaan and L’ooknax.ádi clans of Sitka, Alaska. Although all requirements of the law were not met, the University found that eight of eleven objects in this instance were needed and of central importance to the clans. Again, in recognition of the historical significance of three remaining objects, the University proposed a joint arrangement to send the objects to Alaska where they would be available to the clans. The clan leaders accepted this proposal. However, a second Kaagwaantaan clan leader, through another federally recognized Alaskan entity, made a competing claim for the Kaagwaantaan objects. After careful consideration, Penn was unable to make a determination regarding which leader is the rightful claimant and asked the Kaagwaantaan to determine this among themselves. As of this writing, this case has not yet been resolved.

Native Americans and The Penn Museum Working Together

After mailing thousands of letters to potentially a liated tribes inviting consultation on its collections, the Penn Museum has received a small number of responses and repatriation claims. Tribes are prioritizing consultation and repatriation activities on their own terms and contacting the Museum when they are ready. Our conversations and efforts are not always easy, yet consultation visits are consistently positive and result in the posting of more accurate notices in the Federal Register, successful repatriations, and the building of new relationships. In consort with our Museum mandate of research, teach- ing, collections stewardship, and public engagement, our goals are to help tribes regain their ancestors, to shed light on tribal histories, and to build new relationships with tribes that will outlast the repatriation events themselves. This process requires time, transparency, respect, and good will and fosters an environment of trust and ongoing partnership.

It is fair to say that while our Museum may lament the loss of its collections, our staff have become engaged and respectful participants in tribal consultations. Physical anthropologists Janet Monge (bioarchaeology and osteology) and Theodore Schurr (living human genetic studies) listen to tribes and respect their points of view. This is an opportunity to explain how their research interests and the scientific endeavor can more broadly inform all of our futures, particularly in the areas of health and medicine and in addressing related questions of Native American heritage and identity. While many tribes do not support the analytical testing of museum collections, this is not always the case, as seen in the Tlingit and Yokut examples.

The Penn Museum is engaged in helping students understand the special interests and concerns of native peoples and in training native and non-native scholars in anthropology. Undergraduate, graduate, and law students work with our NAGPRA office gathering the archival documentation needed to understand the history of our collections, conducting revised inventories requested by tribes, and photographing objects to make them available in our online database. Native American Research Education for Undergraduate (REU) grant recipients Rebecca Horsechief (Pawnee) and Herbert Poepoe of Hawaii were given permission by their tribes to participate in repatriations of human remains to their home communities.

Confronting Our Colonial Past and Helping Tribes Heal

Through NAGPRA, Native Americans and museums are rethinking and reshaping what is possible in American cultural institutions. In complying with the law, the Penn Museum acknowledges the historical and political contexts of Indian peoples in the United States and recognizes tribal rights of self-determination. The law mandates that Native American human remains and cultural objects are more than specimens of science and art: they are also cultural property and heritage meaningful to living tribal members.

NAGPRA is an underfunded and open-ended mandate, and tribes and museums have other pressing priorities. Of the 568 federally recognized tribes today, less than half have active cultural preservation offices. Museums routinely need to hear from multiple tribes before repatriation can move forward, and the process often takes several years. While we see consultation as a unique strength of the law, the process is slow on both sides.

The Penn Museum’s experience with NAGPRA reveals that the law requires careful investigation of collections records and the building of relationships with tribes around common concerns. There is no single model that fits repatriation for all tribes. Each native community is different and there are innumerable complexities. It is important not to rush repatriation, and we should not underestimate the challenges NAGPRA brings for tribes. When they are ready, tribes are finding their way to our Museum, and human remains and important cultural items are finding their way home. Through the process, the Penn Museum is confronting its colonial past, helping tribes heal, and creating new relationships and new knowledge that benefit both the Museum and tribes. Just as the Yokuts of California must never forget their ancestors who gave them life, the Penn Museum must also remember that indigenous peoples gave it life over a century ago and continue to do so today.

LUCY FOWLER WILLIAMS, PH.D. is Associate Curator and Jeremy A. Sabloff Senior Keeper of Collections, American Section; STACEY O. ESPENLAUB is Kamensky NAGPRA Project Coordinator; and JANET MONGE, PH.D. is Associate Curator-in-Charge and Keeper of Collections, Physical Anthropology Section.

For Further Reading

Espenlaub, S. “Building New Relationships with Tlingit Clans: Potlatch Loans, NAGPRA, and the Penn Museum.” In Sharing Our Knowledge: The Tlingit and Their Coastal Neighbors, edited by Sergei Kan, pp. 496-508. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Schurr, T.G, M.C. Dulik, A.C. Owings, S.I. Zhadanov, J.B. Gaieski, M.G. Vilar, J. Ramos, M.B. Moss, F. Tatkong, and the Genographic Consortium. “Clan, Language, and Migration History Has Shaped Genetic Diversity in Haida and Tlingit Populations From Southeast Alaska.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 148 (2012): 422-435.