The excavations conducted at Beisan, the biblical Beth-Shan, by the Palestine Expedition of the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, were resumed on the 21st of August last, and continued until nearly the end of December. It is gratifying to record that the finds made during this season were in every way as important as those made during the season of 1925.

The plans for the 1926 season comprised work on the tell and in the vast cemetery to the north, from which the tell is separated by a swiftly running stream called the River Jalud.

Image Number: 135189

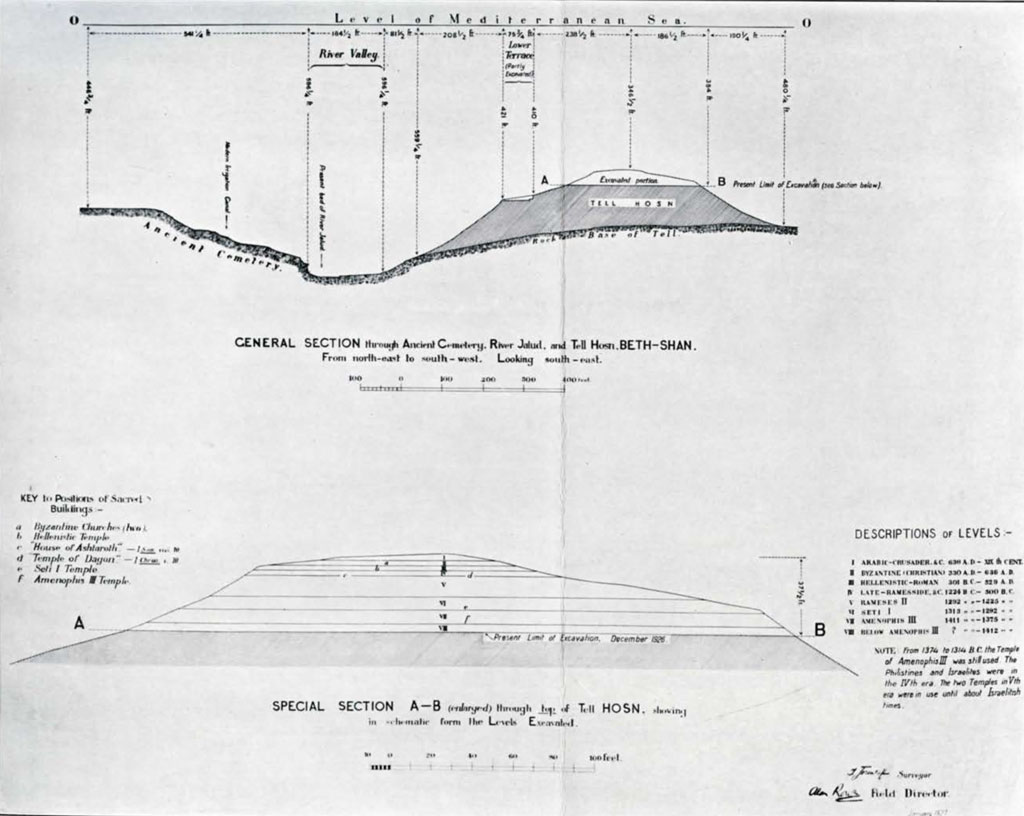

In addition to the actual work of excavation, a comprehensive survey of most of the area was made in order that we might ascertain various important details for our records. The result of the survey is given on the plate specially prepared for this article, which shows a section running through the cemetery, river, and tell, from northeast to southwest. From the upper section on the plate it will be observed that the original top of the mound was 346 feet below the level of the Mediterranean Sea, and that, owing to the contour of the rock base, the height of the mound at the north was 213 feet and at the south 134 feet. The oldest of the eight main superimposed city levels already found on the tell, each equivalent to a historical period, or to a series of historical periods in which sometimes the same buildings were used over and over again, represents the lowest part of the tell in which excavations have yet been carried out. The bottom of this oldest level is about 37 feet below the original top of the tell. The base of the mound itself, along the line of the printed section, is 899 feet in length. It will be seen that the bed of the River Jalud is about 607 feet below the sea level, or 261 feet below the tell top.

Brief details of the eight city levels must now be given in tabulated form, for such are absolutely necessary for a correct understanding of the intricate history of Beth-Shan which is slowly being revealed as a result of our excavations. The relative positions of the levels are given in schematic form in the lower section on the plate, where also the positions of the various churches and temples, already referred to in past numbers of THE MUSEUM JOURNAL, are indicated by letters of the alphabet. That part of the tell in which excavations have not been carried out is indicated on the sections by oblique hatching.

| CITY LEVEL ON TELL | HISTORICAL PERIODS REPRESENTED ON EACH LEVEL | DATES |

|---|---|---|

| I | Arabic; Crusader, etc | 636 A.D. – XIXth cent. (approx.). |

| II | Byzantine, or Eastern Roman Christian (two churches) | 330 A.D. – 636 A.D. |

| III | Hellenistic (temple); Jewish; and Roman | 301 B.C. – 329 A.D. |

| IV | Late Ramesside; Philistine; Israelite; Assyrian; Scythian; New Babylonian; Old Persian, etc. | 1224 B.C. – 300 B.C. |

| V | Rameses II (two temples. Northern one. “House of Ashtaroth” of I Samuel, xxxi, 10, and southern one, “Temple of Dagon” of I Chronicles, x, 10. Both were in use until at least Israelitish times, i.e., c. 1000 B.C.) | 1292 B.C. – 1225 B.C. |

| VI | Seti. Two levels: Late Seti; Early Seti (temple) | 1313 B.C. – 1292 B.C. |

| VII | Amenophis III (temple). Length of reign | 1411 B.C. – 1375 B.C. |

| VIII | Below Amenophis III. Period represented by level not yet identified. | ? – 1412 B.C. |

During the time from 1374 B.C. to 1314 B.C., the temple of Amenophis III was still in existence, so that the VIIth level may really be said to have come to an end at the latter date. Further, the two temples in the Vth level were undoubtedly in use during the early part of the IVth era, that is to say, during Late Ramesside, Philistine and perhaps even Israelitish times, i.e., to about 1000 B.C. As such was evidently not the case with many non-religious buildings, we have, with the above exceptions, and until further excavations decide the point, identified the Vth level as a whole with the era of Rameses II.

The excavations on the tell, during the present season, were carried out in the IId, IIId, IVth, Vth, VIth, VIIth and VIIIth levels, many parts of which remained, and still remain, to be cleared, owing to the fact that in order to fix the dates of our upper levels we were forced to make a large cutting in a part of the mound down to the VIIIth level. Had we simply gone ahead and removed the whole of each city level as we came across it, and not made the cutting, it would probably have been many years before we could have established anything like a correct system of chronology for our excavations. That our method is justified is shown by the important results obtained.

Having thus discussed our levels we may now proceed to describe the discoveries of the last season, the plan being, so far as the tell is concerned, to describe the finds in each level in turn, taking the levels in chronological order.

VIIIth City Level

After we had cleared away the great temple made by Amenophis III, unearthed in the VIIth city level during the 1925 season, we found, this season, in the level below (the VIIIth) traces of what may be still another sacred place. This consists of two cylindrical stone bases, aligned from west to east, with a layer of stones between them. On an adjoining parallel layer of bonded stones was lying a loose block of smooth basalt, long, and roughly shaped. It may be that sacred upright stones stood on the bases, and that the long stone was one of them. Just to the east of the bases is a fireplace, and near by, a semicircular stone with a stone rubber on it which was used for the purpose of grinding corn. To the south of the bases we found a scarab of Thothmes III, who died about thirty-six years before Amenophis III came to the throne. It is therefore possible that the VIIIth level belongs to the time of the former monarch. Some little distance to the north of the fireplace, etc., we discovered three other column bases, which appear to form part of a sacred building which is as yet only partially cleared. Just to the south of these particular bases were unearthed a quantity of fragments of beautifully painted pottery; an ivory inlay showing the figures of a lion and a gazelle on either side of what seems to be a representation of a pool of water with herbage around it; a crude clay model of a lion’s head ; and the rear portion of a well made pottery model of a lion.

Image Number: 144005

VIIth City Level

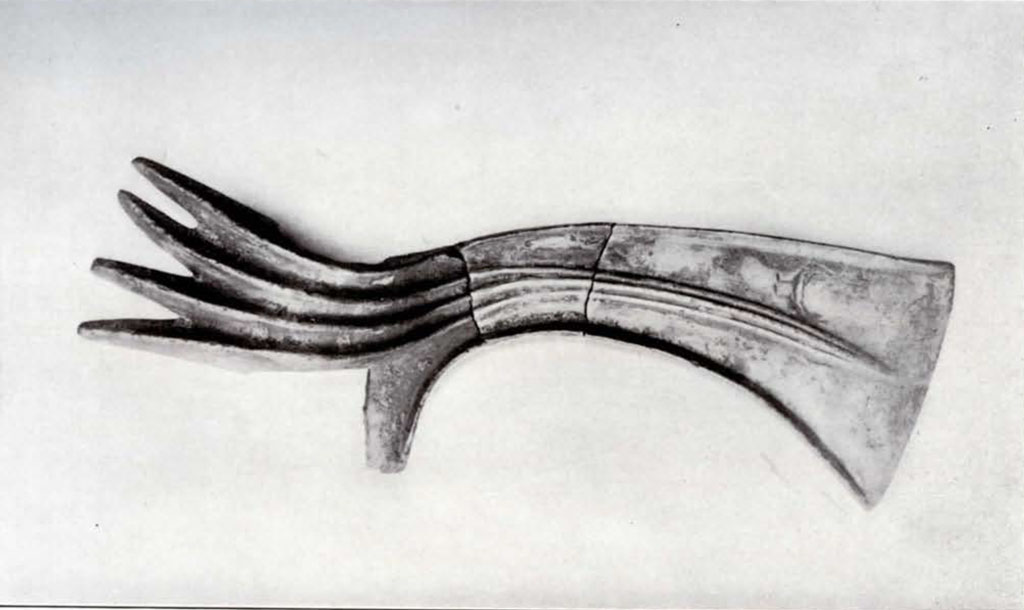

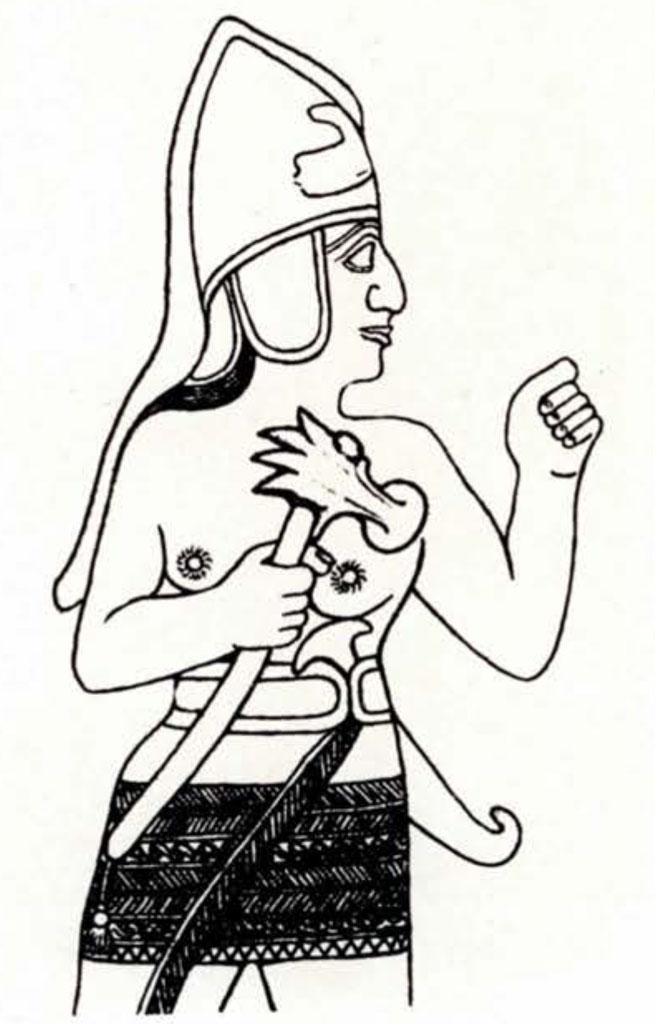

We have now cleared away the whole of the Amenophis temple, further proof of the date of which was furnished by the finding of faience cartouches, and a magnificent finger ring of the same material, all bearing the name of Amenophis III. These had been placed below the walls and floors as foundation deposits. Near them were many inscribed Syro-Hittite cylinder seals, of which nearly fifty have now been recovered from this level; gold rosettes; variegated Egyptian glass vases; six scarabs, two of which were mounted in gold; crescent shaped gold pendants; beads; amulets; and a complete bronze Syrian dagger with inlaid wood handle. Not far from the dagger was one of the most important objects of its kind ever found in Palestine or anywhere else. This consisted of a magnificent Hittite axehead of bronze, having a curved blade at one end, with the other end in the form of a hand with out-stretched fingers, the thumb being downwards.- The blade has a peculiar crescent shaped device on it. This axehead, which is the only example of its kind known, is very similar to one held by a Hittite king figured on the royal gate of Boghaz-Keui, the Hittite capital in Anatolia. It must be remembered that at about the time the temple was built, the Hittites were advancing into North Syria. Hence it is not really surprising to find traces of their culture in Palestine.

In close proximity to the axe and the dagger, and also below the floor of the Amenophis temple, were two most interesting and important objects—one a basalt model of a chair or throne of Cretan (Minoan) type, and the other a limestone model of a table or altar, also of Cretan type. The chair is absolutely identical in shape with certain old Cretan hieroglyphs representing a throne. But although its form is Cretan, the object bears Egyptian emblems. On either side of it is a winged Set-animal, while on its back are depicted a vulture with outstretched wings and the ded-pillar emblem of stability with arms and hands holding the sign of life. The small table has squares painted on its top and sacred trees represented on its base; its shape is identical with that of the table figured in Cretan sealings, where we find it associated with sacred trees. (Compare the “gardens” of Isaiah, lxv, 3.) Near the chair and altar was discovered a model of a sacred tree or perhaps of a sacred standing stone. There is no doubt whatever that these models were associated together as a group of cult objects—probably the throne represented the seat of a god and the god himself, the decorated table the altar, surrounded by trees, on which the offerings were placed, and the tree or stone perhaps the female consort of the deity. Models of certain altars associated with figurines of deities and with cylindrical cult objects not unlike those found at Beth-Shan, are already known from Crete.

With regard to the tree or stone, it must be remembered that in most old Palestinian sanctuaries there were two sacred emblems. These were the mazzebahs (stone columns) and asherahs (wooden poles representing trees), the latter word being translated in the Authorised Version of the Old Testament as “groves,” as for example in II Kings, xxiii, 14. At times even the Israelites departed from the worship of Yahweh and set themselves up asherahs and mazzebahs, as we see from II Kings, xvii (Revised Version), etc.: ” The children of Israel did secretly things that were not right against the Lord their God, and they built them high places (i.e., sanctuaries) in all their cities. . . . And they set them up pillars and Asherim upon every high hill, and under every green tree: and there they burnt incense in all the high places, as did the nations whom the Lord carried away before them . . . They made them molten images, even two calves, and made an Asherah and worshipped all the host (i.e., the stars) of heaven, and served Baal.” Sometimes the pillar represented the god and the pole the goddess.

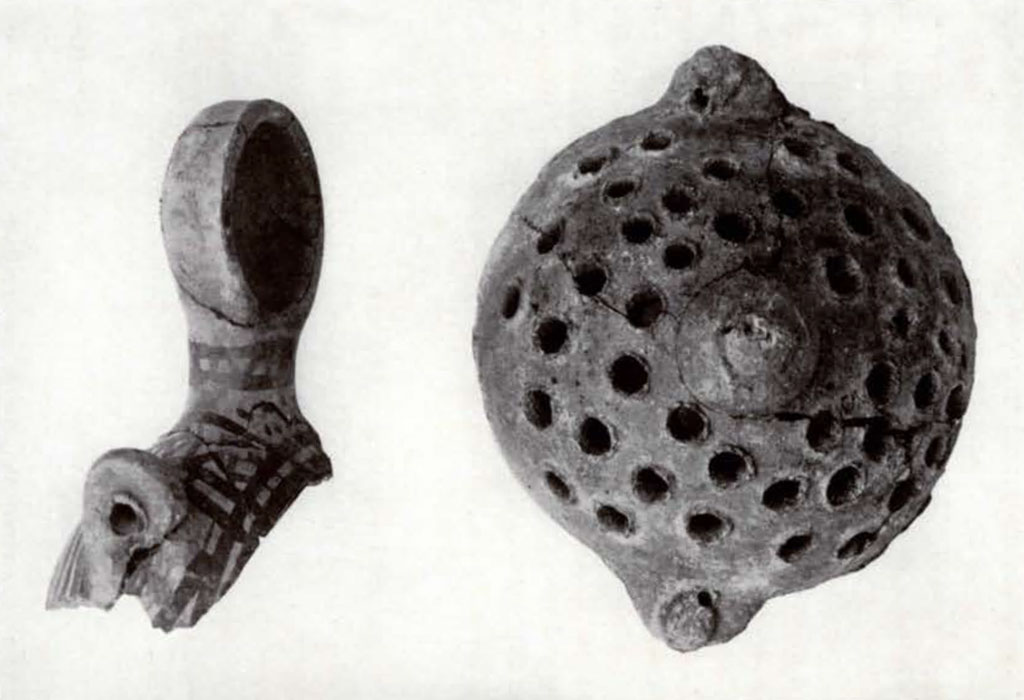

In the floor debris at the southern end of the Amenophis temple we found a clay cylinder terminating in the head of a pig, and also a part of a plaque with a serpent coiled round its upper part. The former object is extremely interesting and belongs to the same class of cylindrical cult objects as those which were found, in 1925, in the temples of Seti I and Rameses II. A Cypriote vase is already known, made in the shape of a pig, of which the head bears a striking resemblance to that of the animal figured on the cylinder just discovered by us.

Museum Object Number: 29-108-365

Image Number: 30181

The excavations of the temple have shown that at the time the building was erected there were two strong foreign influences present at Beth-Shan—the one from Cyprus and the Aegean regions (of the early part of the Late Helladic [Mycenaean] III period, 13751200 B.C.), represented by the cult objects, such as the stand with the pig’s head, the sacred Cretan throne and table, and the other Syro-Hittite, represented by the cylinder seals and the Hittite axe-head. The actual route followed by the introducers of the cult objects was doubtless by way of Cyprus from Crete or South Greece, for there was a Mycenaean kingdom founded in Cyprus about 1375 B.C. The Mediterranean influence which entered Beth-Shan at this time, was therefore connected with this eastern movement of peoples from the Ægean and other regions. The final phase of the Mediterranean influence was represented by the domination of the iron using Philistines, who were doubtless driven out from Beth-Shan by King David about 1000 B.C. With their advent, the Bronze Age, which had hitherto flourished, came to an end. That there was a strong Cypriote-Ægean influence in the old religion of Palestine was never fully recognized until our recent discoveries were made.

In a room just to the north of the temple we came on two large blocks of stone, one laid upon the other, with small stones round them, which perhaps formed part of a great altar of sacrifice, as a great quantity of ashes and fragments of bones was lying on the floor round about. Very few ashes were found near the altars inside the temple. Taking everything into consideration, we may perhaps conclude that the majority of the holocausts were made on the altar outside the actual building, but well within the precincts of the sacred area. Near the great altar, and on the floor of the room, which was of hard beaten clay, we found a basalt incense or offering stand, cylinder seals, a bronze spearhead, fragments of various bronze tools, a basalt door socket, a fragment of a very fine glazed pointed base vase of Egyptian design, and part of a Cypriote kernos or ring stand with small vases attached to it. In the same room were large numbers of trumpet shaped bases of vases made of well baked pottery. Other pottery objects included several cups of different shapes, fragments of a large crater resembling a certain Cypriote type, pottery heads of ducks painted in vivid colors, doubtless from some vessel used for religious purposes, and small glass petal inlays. The same level yielded also bronze arrowheads, a ring shaped vase stand of alabaster, and a large glazed bowl, decorated on the outside with finger prints, similar in make and colour (yellowish-green) to early Arab glazed ware. Fragments of this ware were also found in the VIIIth city level.

Everything points to the fact that the VIIth city level is one of the most important of the levels yet reached, and it is hoped next season to clear much more of it. During the first part of the period it was occupied, kings Amenophis III and Amenophis IV, or, Akhenaten, of Egypt, were communicating with their governors and other peoples in Western Asia by means of the famous cuneiform correspondence (Beth-Shan is actually referred to on one tablet) found at Tell al-Amarna; while towards the close of the period kings Smenkhkara, Tutankhamen, Ai, and Horemheb held, in succession, the throne of Egypt which no longer, alas, owing to Akhenaten’s attitude, held sway over the rich countries of Syria and Palestine. It was not until the time of Seti I, the founder of the VIth city of Beth-Shan, that Egypt once more held Palestine.

Image Number: 30181

VIth City Level

During the last season, work in the VIth city level was confined to the area immediately to the north of the temple of Seti I. The temple itself had already been cleared away in the 1925 season, when its date was accurately fixed by the finding of many faience cartouches bearing the name of Rameses I—the immediate predecessor and father of Seti I—which had been placed as foundation deposits under the walls and floors of the building. The presence of the name of the former king on the objects is accounted for by the fact that Seti was the co-regent of Rameses I for some little time, and that the Syrian campaign was probably inaugurated during the joint reign. However, we find that Seti erected at Beth-Shan a monument, recording among other things his capture of the fort, which is dated in the first year of his reign. A people called the Apiru are referred to in another monument left by him on the tell, though in what connection it is difficult to say, as the text is badly weathered. Some authorities identify them with the Hebrews. The latter monument was discovered, in 1921, in the debris of the IId city level, where it had apparently been used as a door sill. The base on which it evidently once stood was found in 1925 in the Rameses II stratum. The former inscribed monument was found in 1923, in the Vth city level, and as it was erected near a large stele set up by Rameses II, it must be that Rameses brought it up, together with the other Seti stele, from the lower level, when he built his new city on the tell top.

The VIth city level seems to consist, at least outside the temple area, of two distinct levels, which we have called Early Seti and Late Seti respectively. The temple itself does not appear to have been affected by the addition of the extra stratum of houses, which never covered any part of its area, so we must assume that religious observances were carried out in the building for the whole of the time represented by the VIth level.

In the Early Seti level to the north of the temple we found some very interesting objects, which comprise a well made pottery model of a hippopotamus on a flat base, a part of a pottery model of a horse showing the animal’s head with headstall, Egyptian amulets, and so on. Near by were some large teeth which have been identified by the British Museum as those of the upper left cheek of a small equine—almost certainly an ass. In this connection it may be interesting to recall the fact that several molars from the right lower jaw of an ass were found many years ago in Tell el-Hesy in Palestine. Not far away from the teeth were fragments of a hard metallic pottery inlay, apparently used to imitate inlays of ebony and grained wood; a pottery figure of a serpent on a flat base (pierced with holes for suspension on a wall); and part of a cylindrical cult object. Another important find was an open crucible of pottery with particles of bronze still adhering to the inner surface.

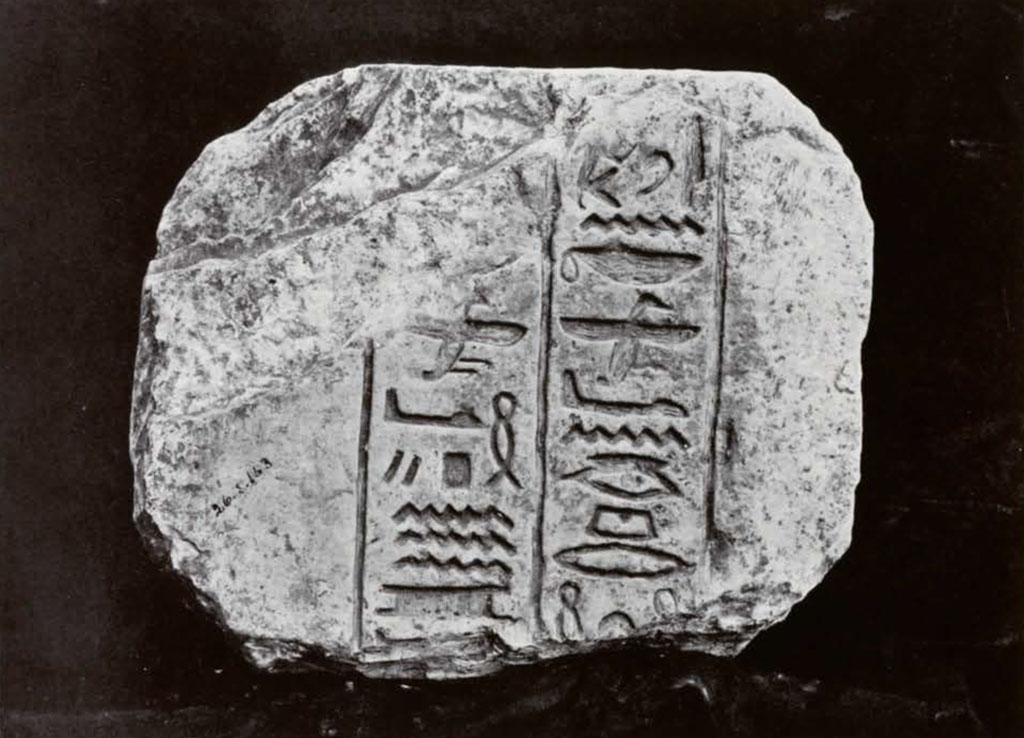

From the Late Seti level, also to the north of the temple, came a very valuable treasure in the shape of a solid mass of silver ingots, earrings, pieces of wire, etc., and a gold armlet, three and a half inches in diameter. Before we disintegrated this mass, the weight of which was 2 pounds 15 ounces avoirdupois, we noticed that its exterior bore traces of the cloth bag in which it had originally been kept. In a room just to the east of that in which the treasure was unearthed we saw traces of a large stone doorway, comprising a sill, door-socket, door-jambs, etc. Two fragments of the door-jambs were found to be inscribed. One of them has a double band of hieroglyphs on it which contains part of an address to the Egyptian solar deity: “Praises be to thee, O beautiful one, who possessest everlastingness . . . thou didst fashion the Nile . . .”

Museum Object Number: 29-107-947

Vth City Level

When Rameses II built the Vth city level he erected two temples in it, particulars of which have previously been given in THE MUSEUM JOURNAL. These two temples, which were still in use during the early part of the period representing the IVth city level, are evidently those referred to in the Old Testament, the northern one being the “house of Ashtaroth ” of I Samuel, xxxi, 10, and the southern one, the “temple of Dagon” of I Chronicles, x, 10. The southern temple had already been removed during the 1925 campaign, so in the past season it was necessary to remove the northern one in order to reach the levels below it. The latter building contained four stone column bases in situ, and after they were taken away we found below one of them a part of a box-shaped object with serpents adorning its sides. Some of the bricks in this temple had large signs imprinted on them while still wet. One sign was like a circle with a bar across it, another like a shepherd’s crook, another is a diagonal line, another like a capital X having two parallel perpendicular strokes within one of its angles, and still another brick has a sign like a Greek capital pi (Π) placed with its open end towards the centre of an X. Meanwhile work was continued to the east of the great Dagon temple where many rooms were cleared out, providing us with a quantity of pottery, loom weights, and so on. The pottery includes fragments of a large eight handled pot and of a four handled jar, lentoid flasks, of which some recall those found with certain anthropoid sarcophagi in the cemetery (to be referred to later on), while another has lug handles and a spoon shaped extension on its top. The brick walls of the period of Rameses II are as a rule very solid and are built upon a foundation of stones which are often very large and which sometimes occupy a space considerably greater than the width of the wall. Some walls had wooden beams or planks bearing upon the stones to make the foundations level. The wood has, in process of time, turned black and may be easily, though erroneously, supposed to have been burnt. In other cases the walls rest upon beams alone, without any layer of stones below, or even upon the debris of the tell itself.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-946

IVth City Level

During the early part of the period represented by the IVth city level, that is to say until the death of Rameses III in 1225 B.C., Beth-Shan was still held by the Egyptians, whose mercenary troops, mostly of Ægean-Anatolian origin, under Egyptian officers, had been in occupation of the place ever since the time of Seti I. A statue of Rameses III was found on the tell in 1923. Soon after the death of this king, the Philistines, a people also of Ægean-Anatolian origin, took possession of the fort, doubtless amalgamating with their kinsmen, the old mercenaries, who were already there, and defeated Saul of Israel upon Mount Gilboa, to the southwest of the site, and placed his head in the Dagon temple and his armour in the “house of Ashtaroth.” The Philistines were driven out from the fort about 1000 B.C. by King David, when the Israelites took over the place. Beth-Shan was subsequently plundered by King Sheshonk I of Egypt in 926 B.C., and was under Assyrian occupation from the Eighth Century to 626 B.C., the time of the Scythian invasion. One of the remains of the Assyrian occupation consists of a magnificent onyx cylinder seal, dating to the older Cassite Dynasty of Babylon, which was found on the tell last season. The Scythians, who were Indo-Europeans from the far north, entered Western Asia, overrunning Assyria, Palestine, etc. In much later times Beth-Shan was known as Scythopolis, or “City of the Scythians,” but whether the first part of this name refers to the Scythian invasion or is a corruption of some word other than Scythian, is not known. Nebuchadnezzar invaded Palestine and Syria in 600 B.C., but in 538 B.C. the New Babylonian Empire which he had founded, came to an end, for in this year Cyrus, the Persian, captured Babylon and founded the Old Persian Empire. Alexander the Great put an end to the latter empire in 332 B.C., and from 301 B.C. onwards Palestine was under the rule of the Ptolemies. The IVth city level of Beth-Shan came to an end with the advent of the Ptolemies. Some of the earlier walls of the above level are of a soft reddish brick, built upon a foundation of smallish stones, while others are comprised of rubble covered with plaster. Owing to the way in which the whole level has been successively destroyed and rebuilt, it is impossible to say exactly to what period any given room belongs; and further, as might be expected, unbroken objects are very rarely discovered in it. We found, however, in addition to the above mentioned cylinder seal, two glass scaraboids; a number of beads and of unpierced pebbles which were probably meant to be turned into beads; large bronze fibula; fragments of colanders and of a jar with a false spout. Beneath the floor of one room a jug was discovered which contained remains which may prove to be the bones of a child. If so, we have here further evidence of the old Palestinian custom of burying infants under the floors of dwellings. Both the jug and its contents have been sent to the University Museum, where the latter will be identified.

Museum Object Number: 29-103-953

IIId City Level

The IIId city level represents the Hellenistic, Jewish and Roman periods. From 301-198 B.C. Palestine remained, with short interruptions, under the rule of the Ptolemies. It then came under the domination of the Seleucidæ. These were kings of Syria who took their name from Seleucus, a general of Alexander the Great, who subsequently became the founder of the Syrian monarchy. About the third century B.C. a large stone temple, perhaps dedicated to Astarte-Atargatis, or to Dionysos, was erected on the tell. It was 72 feet wide and 121 feet long, and its entrance was at the west. In a reservoir to the south of it was found the head of a large marble statue, and also the fingers of a marble colossus. Beth-Shan yielded to John Hyrcanus, the prince and high priest of the Jews, in 107 B.C., and remained under Jewish rule until the arrival of Pompey in 64 B.C. Thus commenced the Roman period, which may be said to have lasted until 330 A.D., when the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman Christian) period was inaugurated by Constantine the Great. With the conclusion of the Roman era the IIId city level came to an end.

During the whole of this time, and also during the time equivalent to the IId and Ist levels, dressed stone was used for all the buildings on the tell; the buildings in the previous levels were invariably made of brick.

Our excavations in the Ind level, during the last season, were carried out on the southeast part of the tell, where many rooms, undoubtedly belonging to Græco-Roman times, were excavated. One of them had a floor consisting of a cement pavement. Hellenistic lamps and pottery (black varnished or red glazed) were found below them when they were cleared away; and the pottery immediately under the cement floor, while lacking any clearly Hellenistic features, showed no specimens of the ribbed ware which becomes common in the late Roman and Byzantine times. In one of these Græco-Roman rooms was found the toe of a large bronze statue. Other objects of a definitely Hellenistic character comprised a part of a female figurine and a fragment of a plate painted with a wreath of ivy.

IId City Level

The IId city level is purely Byzantine, and it lasted for about three centuries, coming to an end in 636 A.D. with the conquest of the Arabs. Very important Byzantine remains have already been found on the tell, chiefly during the years 1921-1923, and include two churches, one of basilica form (IVth century A.D.), and one of rotunda form (VIth century A.D.), particulars of which will be seen in former numbers of THE MUSEUM JOURNAL. The chief work carried out in 1926 in this level was the partial removal of three huge Byzantine stone walls, enclosing on the north, south and east sides, the area adjoining the above-mentioned Græco-Roman rooms. The northern wall was found to have its foundations, for a considerable stretch, running at a very low level (about the VIth city floor level). It seems possible that the wall was originally intended to form part of a reservoir. Several stones from this wall, like stones from other walls of the same age, have certain letters of the Greek alphabet marked on them. They are merely masons’ marks.

Nothing can here be said about the Ist city level, as practically the whole of the Arabic stratum was cleared away from the tell in 1923.

Recent Finds In The Cemetery

The great cemetery of Beth-Shan, which is undoubtedly one of the largest in Palestine, extends along the sloping northern side of the River Jalud. It contains innumerable graves of all periods from the Bronze Age to the Byzantine era, about forty-four examples of which have been cleared out during the last season with most satisfactory results. As a rule the very oldest graves in the cemetery are found at the top of the slope, while those of the other periods are cut indiscriminately over the whole of the valley side. The graves very frequently break into one another, causing, in many cases, a great disturbance of the original burial equipment. It is thus a common occurrence to find in a single tomb objects belonging, say, to the time of the anthropoid burials and to the Byzantine era, periods which are separated from one another by an interval of 1500 years.

Middle Canaanite Period Burials

The earliest type of bronze age grave we have just discovered (about the beginning of the Middle Canaanite Period, 2000-1600 B.C.) consists of a roughly circular subterranean chamber with a small passage leading to it, the entrance of which is blocked by a single large stone. In a good many instances, owing to the poor nature of the rock, the roof has collapsed, thus destroying the body and some of the pottery, if such had not already been destroyed by the ancient tomb robbers. The bodies appear to have been laid on their sides in a crouching position, no systematic orientation of the corpse being carried out. In one of these graves were a large ledge handled pot, a single handled jug, an open (Canaanite) pottery lamp with four spouts, and so on. From certain of these interments, including that mentioned above, have been recovered long pointed javelin heads of bronze. No articles of jewellery or adornment whatever have come from these graves, the people connected with which must have been in a somewhat low stage of culture. It is interesting to observe that no objects which could be ascribed to a foreign source were found with the bodies.

Pottery Anthropoid Burials

The next in order of date of the graves found by us are those containing large pottery anthropoid sarcophagi of the socalled “slipper” type. In contrast to the roughly round shape of the earliest bronze age tombs, the “anthropoid” tombs are roughly rectangular. One such tomb consists of a large underground hail with a low entrance at the bottom of a shaft which leads from the ground surface above. The hall has a rectangular recess for a sarcophagus to the north, east and west; the recesses on the east and west are raised a step above the floor level of the hail. In this particular tomb at least three sarcophagi were found, one belonging to a woman. Practically no jewellery was found with them, but it may be worth drawing attention to the fact that the tomb contained a flat bottomed jar having ledge handles of a peculiar form, the clay when still wet being folded over in three flaps so as to make a semicircular handle. Jars of this type have been found on so many other occasions inclose connection with anthropoid burials that it seems almost impossible to reject the conclusion that they are contemporary with them. Such jars, however, are usually regarded as belonging to the earliest bronze age.

All the sarcophagi in these tombs are cylindrical in shape, and taper down towards the base, their maximum diameter being about where the shoulders of the corpse would be when placed in them. They all have moveable lids upon which are modelled in high relief the features of the deceased with crossed arms and hands. At the base of some of them the feet have even been represented, but this characteristic is very rare. One of the sarcophagi has just been sent to the University Museum.

Our evidence certainly seems to indicate that these interesting burials are mostly those of Egyptian mercenaries who came from the seacoasts and islands of the eastern Mediterranean. They date from about the time of Seti I, or Rameses II, to the time of Rameses III, or perhaps even slightly later. Sarcophagi very similar to ours have been found in Egypt at Tell el-Yahudiyeh (Mound of the Jewess), at Tell Nebesheh near Lake Menzaleh, at Saft el-Henneh to the east of Zagazig in the Delta, and at Suwa to the south of the latter town. The Egyptian examples date, according to their discoverers, from the XVIIIth to the XXVIth Dynasty (c. 600 B.C.), the earliest being of the time of Thothmes III (1501-1447 B.C.), and nearly all, like ours, have Mediterranean (including Ægean and Cypriote) pottery and other objects associated with them.

Among the things that have been unearthed with the Beth-Shan anthropoid sarcophagi may be mentioned “stirrup vases” or Bugelkannen, lentoid flasks, and other Mediterranean pottery. A most interesting object was a gold foil mouthplate, lozenge shaped, with a hole at each end, which was originally tied over the mouth of the body before it was laid in the sarcophagus. Similar mouthpieces have been found in Cyprus and in various countries directly affected by the Ægean civilization. Other associated objects are Canaanite pottery lamps, some with spouts for four wicks; spindle whorls; small bead-spreaders inscribed with figures of Egyptian deities; part of a beautifully made onyx figure of the god Bes; pendants and beads of carnelian, steatite and onyx; spearheads and coiled bangles of bronze; earrings of bronze, silver and gold; plain finger rings of bronze and silver; scarabs, some mounted in gold, ranging in date from the Hyksos period to the time of Rameses II (one bears the name of Thothmes III); and a bronze ring with a scaraboid attached to it. Certain of the burials even had Egyptian ushebti figures (i.e., models of field workers for helping the deceased in the other world) with them, which fact, although very interesting, is not surprising when we consider that the religion of the mercenaries must have been strongly influenced by that of their Egyptian officers. As a matter of fact, the presence of the sacred Nilotic amulets and figurines shows that whatever deities of their own the mercenaries may have worshipped, they probably also revered some of the gods of the Pharaohs. Further, it was quite an easy matter for them to identify with Hathor or Isis of Egypt (and incidentally, with Ashtoreth of Palestine) their own great Mother Goddess, who was universally worshipped over the whole of the regions of the Ægean and the northern parts of the eastern Mediterranean.

Græco-Roman and Byzantine Burials

Very important objects of the Græco-Roman and Byzantine ages were found in the cemetery last season. The Græco-Roman tombs are usually of the kokim or loculus type, which consists of a rectangular rock cut hall with loculi, or oblong chambers, cut in its sides. Into these were deposited either the bodies alone, or else the sarcophagi containing them, the feet or the head being placed towards the hall. Often after the side chambers were filled up, burials were actually made in the hall itself, sometimes in sarcophagi and sometimes in trough-like graves, excavated in the floor and covered with slabs. In other cases roofed in pits are actually found in the floor of the loculus itself. Children as a rule were buried in small slots made in the hall floor or in pottery boxes with sliding lids. The roof of the hall is usually vaulted, and, like the walls, covered with a thin layer of white plaster. Each tomb has a flight of steps leading down into it, with a stone door near the top step. No triclinium, or couch used in conjunction with the funerary repasts, such as is to be seen in the cemeteries at Alexandria and elsewhere, has been found in our tombs of the Roman era. Certain of the Græco-Roman tombs were reused in Byzantine times. From one such tomb came a small bronze pendant in the form of a Maltese cross. Another type of Hellenistic tomb consists of plain graves excavated in the rock, each of dimensions sufficient for a single burial. Some of these are cut in a ledge in the hillside. A flight of rough steps was found in the face of the rock leading down to this particular ledge.

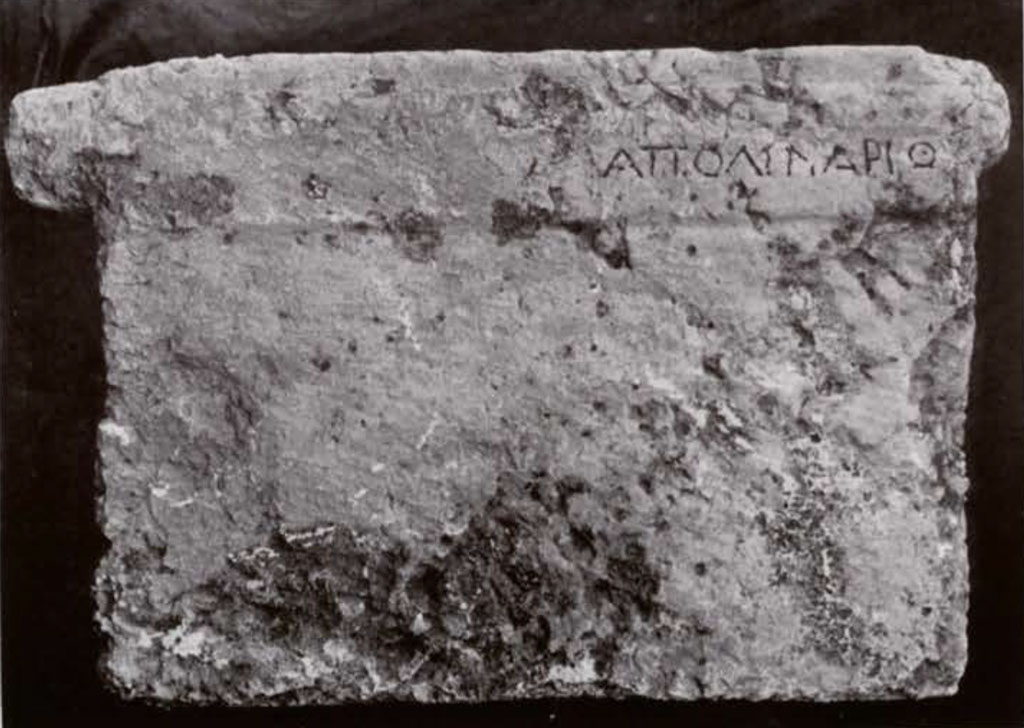

The Christian (Byzantine) tombs as a rule consist of a small vaulted rock-cut hall with vaulted graves on three sides of it. The graves, which are divided from the hall by means of small walls of stone covered with plaster, usually have a rock headrest at one end of them. Like those of the Græco-Roman age, the tombs of this age have a flight of steps and a stone door. A door from one Christian tomb provided an unusual feature, in that it bore, in an inscription in Greek characters, the name “Apolinarius,” which presumably indicates the occupant of the sepulchre. From the same tomb came a basalt lock—a device for fixing the bolt which closed the door on the inside. A certain Christian tomb had crosses in red paint, varying from three to four, over each grave.

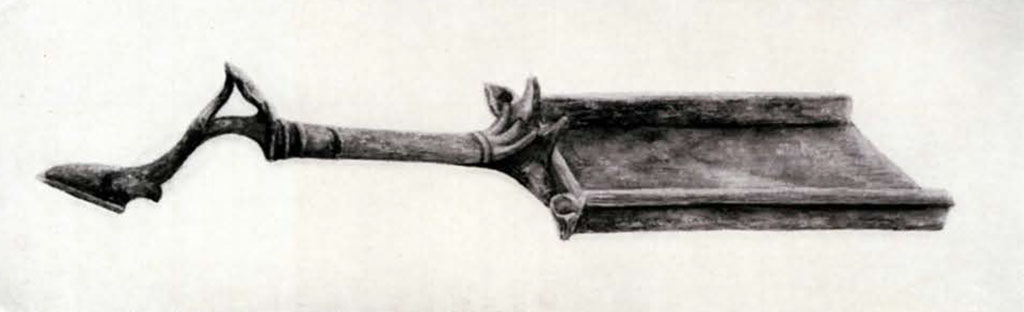

The objects found in the graves of the Græco-Roman and Byzantine periods are very interesting and important. Among them may be mentioned alabaster vessels; a good quantity of pottery of all shapes, some of it being of the fine red polished type; many nice glass vessels, including lacrymateria, or tear bottles; askoi (i.e., wine-skin shaped vessels), one in the form of a ram; pottery statuettes, one probably representing the goddess Isis with her child Horus; part of a statuette showing a rider on a horse; very many pottery lamps; glass mirrors set in limestone frames; sistra, bells, buckles and knives, all of bronze; keys of iron; a bronze lancet; a small bronze jug of good design; bronze tools; Byzantine bronze finger rings, some having crosses on their bezels; bangles and mirrors of bronze; a quantity of glass beads of various colours and forms; decorated bone hairpins, and so on. A very interesting find was a cubical pottery die, marked like our modern dice, with points numbering from one to six. A magnificent incense shovel in bronze, with a handle in the shape of an animal’s leg and hoof, was really one of the best objects of Roman times ever found in the cemetery. With it was a fragment of a bronze sistrum. In certain tombs crudely made limestone portrait busts, some bearing the name of the deceased, have been brought to light.

The excavations carried out at Beth-Shan by The University Museum have yielded treasures of the very greatest value, not only for the history of Beth-Shan but also for that of Palestine in general.

Museum Object Number: 29-103-757

Image Number: 30219a

Museum Object Number: 29-108-27