In the JOURNAL for December, 1923, Dr. Fisher described the excavations at Beisan. The present article has particular reference to that part of the excavations that had to do with the early Christian Church on that site. That Church, built in the early part of the fourth century, is the oldest Christian Church that has ever been brought to light by excavation in the East. It presents many interesting features and gives clear indications of the architecture and decoration of Eastern churches at that early period. Among the interesting details recovered during the excavation are the fine mosaic pavements, now in the University Museum and the mosaic pictures on the walls, the existence of which is proved by quantities of small tesserae in colours and gold indicating walls covered with mosaic decorations on a gold ground that imparted to them the same splendour that characterizes the later churches at Constantinople, Salonica and Ravenna built during the sixth century. The ruins of this early sanctuary also show clearly the transition from the Basilica to the Round, and there is evidence that there were extensive ecclesiastical buildings grouped about the Church.

Scythopolis, as Beisan was called during the Classical period, was, in the beginning of the Christian era, at the height of its prosperity and grandeur. Lying in the midst of a well watered fertile region, one of the most productive in Palestine, it had amassed great wealth, and because of this and its dominating position at the centre of the chief arteries of trade between east and west, it had become the chief city of the Decapolis. In population it exceeded Jerusalem and was noted for the number and magnificence of its public buildings. Furthermore, it was one of the great centres of Greek Classical culture in the East. On the summit of its acropolis was the great temple of Dionysius, whose cult, with that of Astarte, held undisputed sway throughout the northern Jordan valley. Indeed Scythopolis laid claim to being the birthplace of the god, for which honor there were, however, many other claimants.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-933

Image Number: 41580

Some Biblical authorities identify Bethabara, the scene of the Lord’s baptism, with a ford of the Jordan, only a few miles northeast of the city. Whether this is correct or not the town must have been familiar to Him and His disciples, and they may often have passed through its streets on their journeys to and from Galilee. The details of their lives would have formed one of the exciting topics of conversation in the local market. Yet pagan influences were so deeply rooted that Scythopolis was one of the last great Palestinian cities to give a home to Christianity. Besides the Greek and Roman people there had been for several centuries a strong Jewish element, which had from time to time played an important part in its history. For example, in the year 107 B.C. they had been so powerful that they were able to hand the city over to John Hyrcanus. Again as late as 65 A.D. they took sides with their pagan fellow citizens in defending the city against the attacks of bands of their own countrymen who were roving through the country during the rebellion against Roman rule. This act of loyalty does not seem to have influenced the friendliness of the townspeople towards them, for shortly afterwards they enticed the Jewish population outside the walls and treacherously massacred some 13,000 of them.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-933

Image Number: 30071

It is not likely that Christianity obtained much foothold in Scythopolis until the end of the second century. Under the emperor Diocletian (245-313), the faithful suffered severely in the persecutions which he instituted as a political measure throughout the empire, and numbers were slaughtered in the theatre of Scythopolis. This building stood just below the southern slope of the acropolis and although now badly ruined is still one of the best examples of Classical buildings on this side of the Jordan. Towards the end of this period, Procopius, a native of Jerusalem, was made lector and exorcist of the local Christians, and shortly after Patrophilus was elected their first bishop. After the end of the persecutions and most probably because of them, the new religion spread rapidly, and during the ensuing fifty years became the dominating force in Scythopolis. In the year 318 the city was of such importance that its bishop, Patrophilus, was sent to attend the council held in Palestine, and seven years later to that famous one at Nicaea, the first general council of the Christian church. Eusebius was exiled to Scythopolis in 355, by the emperor Constantius II for refusing to take part in the condemnation of Athanasius. While here he met Gaudentius, bishop of Novara, and also Epiphanius. Under the influence of these men, who gathered around them groups of students and adherents, the city became a great monastic centre, and produced from time to time men famous in the annals of the church, among them St. Basil and St. Cyril.

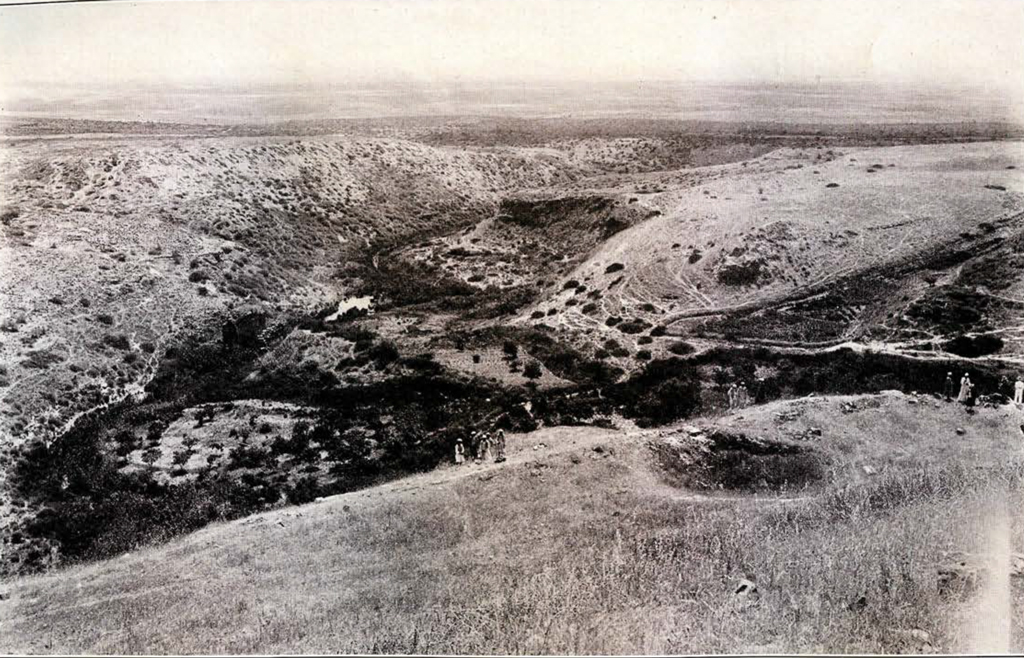

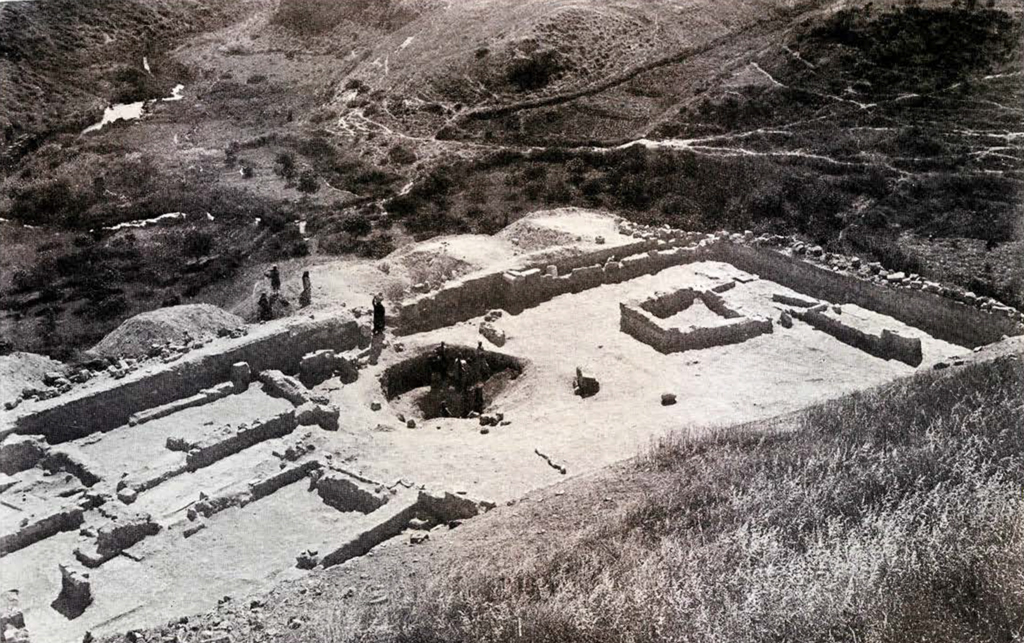

At this time the central hill, or acropolis of the city, had approximately the size, shape and appearance that it now has. Many centuries of building and destruction had formed upon the original rocky eminence an enormous accumulation of debris. The broad terrace some 90 feet below the top, which is the distinguishing feature of the hill, was already in existence in the Roman period. Three of the sides were precipitous and access to the top was practicable only on the west and here throughout all the different periods, had been the entrance to the upper town. In the Greek and Roman occupations a finely built gateway had existed at the northwest corner of the terrace, and from it a broad roadway paved with regular blocks of basalt had wound up the gentle northern slope to the great temple on the summit. It remained only for the Christian builders to adapt this great artificial platform to their own structures.

Museum Object Number: 29-108-105

Image Number: 30291

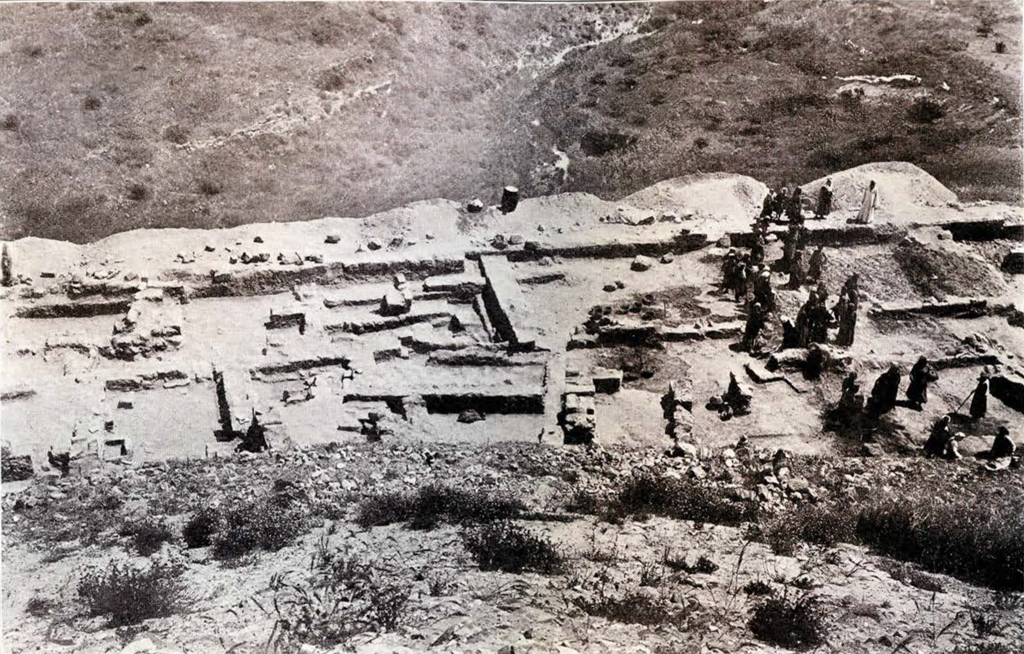

Not until after the reign of Diocletian could the Christians have been strong enough to usurp the site of the pagan temple, and it is more than probable that it was under the leadership of Patrophilus that the monuments of his faith began to displace those of its pagan predecessor. We may give to him the credit of preparing the way for the new church even if he did not supervise its actual construction. It was placed on the summit of the hill whence it overlooked the entire city and formed a landmark for miles to the northwest up the valley of Jezreel and for long distances up and down the Jordan valley on the east. Practically the whole of the old pagan temple was razed to the ground, only a small portion of its foundations remaining along the west where they were buried under the new masonry of the church. Much of the old material was broken up into smaller building stones for the walls, and the great drums of the columns and their huge Corinthian capitals which could not be easily utilized were used as filling material for the platform on which the church was to stand. This platform was raised six to eight feet above the preceding level and was made with earth and debris taken from any available spot, so that we found it filled with pottery and other objects of many different periods mixed together. The old roadway served for the new approach, some slight alterations at its upper end being necessary to make it conform to the new plan.

Image Number: 41607

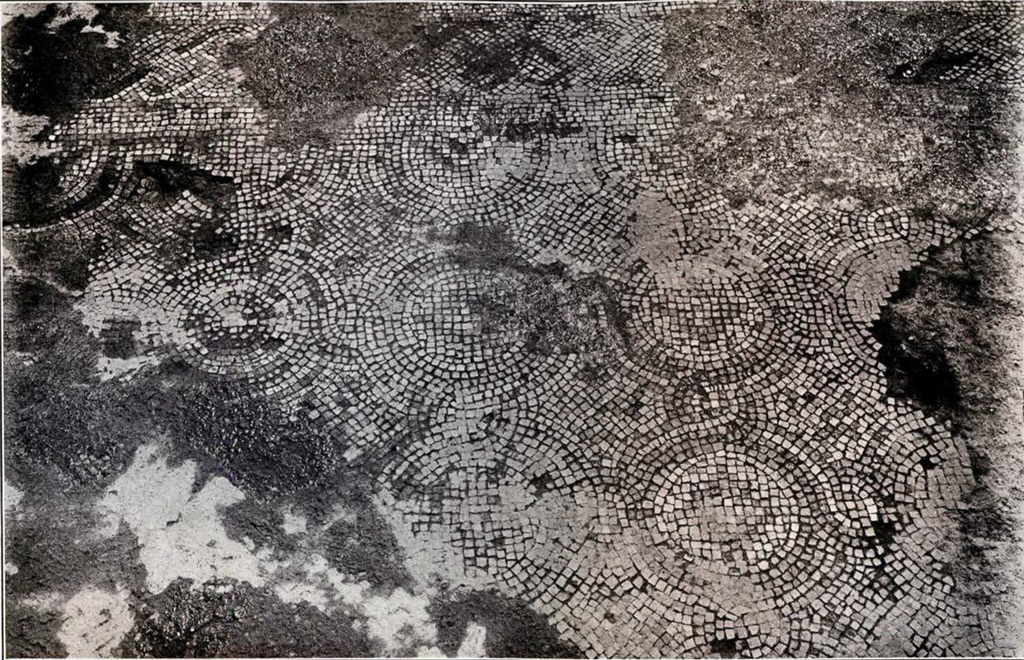

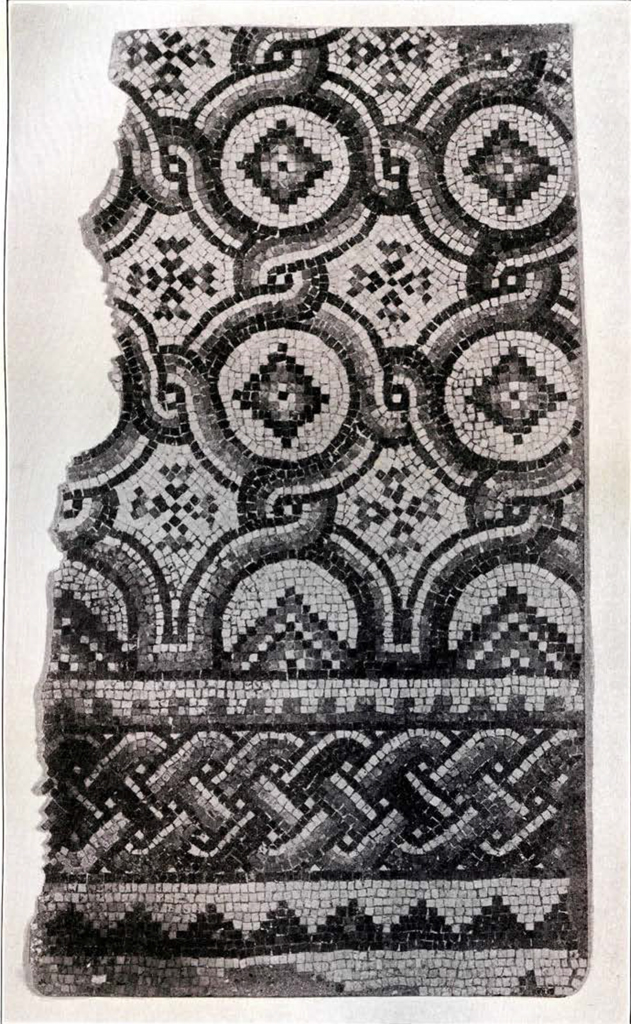

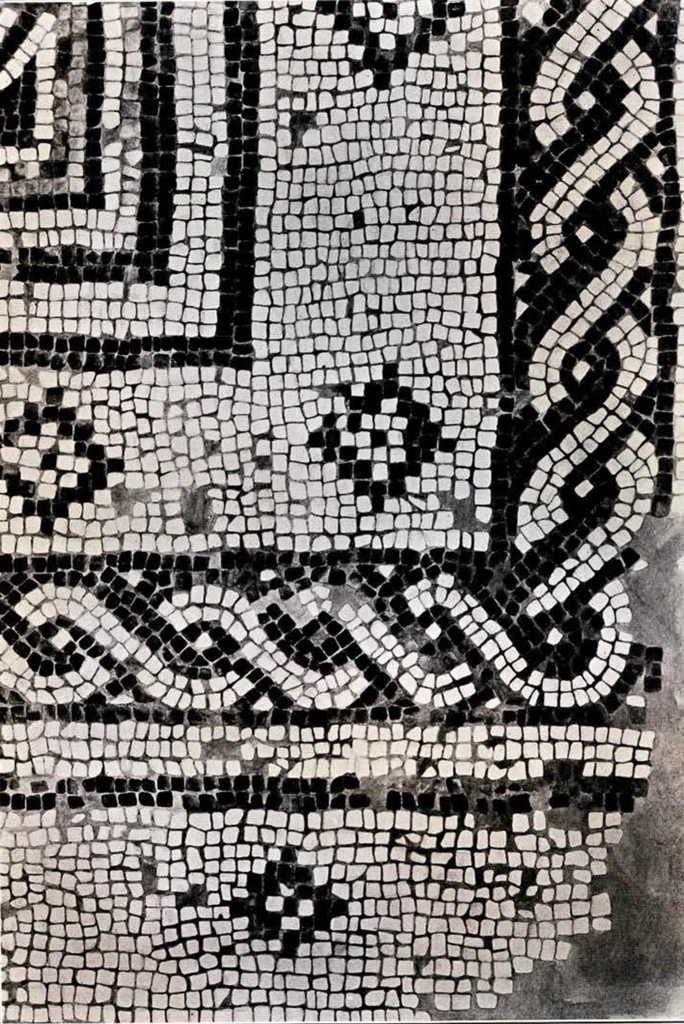

The church was built in the regular Roman basilica form, a long rectangular building containing a central nave and side aisles. Across the western facade extended a greater narthex or vestibule and at the east end a small semicircular apse contained the high altar. The floor of the vestibule was covered with red and white marble squares, enclosed within a border of plain brown stone. The central nave appears to have had a similar floor, but consisting of white marble only. The two side aisles on the other hand had elaborate pavements of colored mosaic, of which only a small broken fragment remained at the western end of the southern aisle Here the pattern consisted of large diagonal panels bordered with scrolls and containing bowls or jars filled with conventional flowers. At either end of the main vestibule were small chambers with mosaic floors, that on the north having a well balanced design of large and small interlacing circles inside an elaborate scroll border Other rooms on either side of the apse had colored marble floors like that in the western vestibule. All through the debris were found quantities of delicately colored glass mosaic, and many tesserae with gilded surfaces. These could only have been used on the walls and while the latter were entirely destroyed, we may picture them as originally covered with Biblical scenes worked out in color on a golden ground. The interior of the building was further embellished with rows of green and white marble columns, the precise arrangement of which cannot be determined as they were reused later in a reconstruction of the church. The space in front of the altar was enclosed with a marble rail, composed of panels of thin slabs between round topped square posts. The faces of the panels were decorated with wreaths and crosses. Some of the fittings of the church were discovered in the houses of the lower terrace where they had been taken during the destruction of the church. Both of the great bronze knockers of the main door were found, finely modelled lion heads holding heavy rings in their jaws. Also several of the bronze frames for the ceiling lamps, and a small stand lamp presumably from the altar. The roof was constructed of wooden beams supporting planking on which were laid flat terracotta tiles, numbers of which were found all over the area.

The entire upper hill was enclosed with a heavy masonry wall, starting at the northwest gate on the lower terrace and following closely the contour of the hill. The whole area between this wall and the church on the summit was filled with closely grouped buildings, some of them obviously large storehouses or stables, while others contained portions of fine old floorings of marble and of mosaic. It may be that the entire acropolis was reserved for a great ecclesiastical complex, containing some at least of the monastic buildings, the residences of the higher church dignitaries and the buildings in which were stored the tithes and the supplies for the various establishments.

Within the church and just north of the altar we discovered an empty tomb, built of masonry and plastered with gray cement. It is tempting to presume that this represented the resting place of Patrophilus, the first bishop and the founder of the church, as it is the most natural place for him to have been buried. Only one other burial was found within the limits of the summit of this period and that was obviously of much later date. The first church must have been completed before or just after the death of Patrophilus. In the year 361, under the emperor Julian another series of persecutions of Christians throughout the empire was inaugurated. Scythopolis suffered heavily. The mob, who had perhaps some feeling of vengeance for the use of their former temple site as a Christian shrine, looted and burned the sacred edifice and at the same time desecrated the tomb of Patrophilus, scattering his bones and using his skull as a lamp. Just how complete the destruction was must remain a matter for speculation but the marble and mosaic pavements suffered severely not only from the intense heat of the burning roof beams which had fallen in on the floor but from deep indentations made by portions of the heavy masonry falling upon them. Still further portions of the walls may have been overthrown during a violent earthquake the following year, which the Christians attributed to Julian’s attempt to restore the Jewish temple in Jerusalem.

After these violences came a quick reaction. The church prospered and became within the next few years stronger than ever before. The commanding position and natural wealth of the city still tended to give it a leading place amongst the cities of the country, and it shortly became one of the centres of the faith and noted for its many imposing churches. No doubt the restoration of the great church on the summit was one of the first works undertaken. At this time the old basilica form of church was rapidly being superseded by the circular plan borrowed from the East, and practically all the churches of the late fifth and early sixth centuries in Palestine and Syria were built under this influence. Therefore it was not surprising to find the second edifice on the acropolis at Scythopolis having as its main feature a large circular rotunda which took the place of the former nave. Certain features of the first building were retained in the new structure, as for the example the western vestibule or narthex and the apse. The narthex seems to have suffered least from the fire and earthquake, and even its floor does not seem to have required much restoration. The rotunda was laid out so as to fit in between the vestibule and the apse, and is for the most part a fair piece of engineering. It is significant that in laying out the circle, great care was taken that the new foundations of the rotunda did not cut across the tomb which lay to the north of the altar and directly in line with the new masonry. The adjustment of the circle to the tomb caused a slight flattening on the western side where it adjoined the walls of the vestibule. Surely there was some special holiness about the tomb which the restorers of the church took special pains to respect. Whether the bones of Patrophilus were ever collected and replaced in the tomb we cannot say. When found the tomb was empty and had probably again been ransacked when the town fell into the hands of the Arab invaders two hundred years afterwards.

The rotunda had two concentric walls, the outer forming the main enclosing wall and the inner, of somewhat slighter construction, carrying a part of the weight of a thin dome covered on the exterior with a wooden or tiled roof. This inner wall was pierced with four large openings, each subdivided into three by two of the old marble columns. All of the latter were reused except two which had been so damaged when they fell that they were left lying and embedded in the new foundations. The rotunda was paved with fragments of the old marble flooring badly fitted together, and the encircling aisle opposite the narthex had a mosaic floor of simple pattern, rude squares with small crosses in the centres. For the remainder of its length it had a pavement of small marble tiles like those in the previous building. The lower part of the walls were faced with a veneer of thin marble slabs, and above these the walls appear to have been simply plastered and painted. The entire reconstruction appears to have been done with old materials and workmanship and decoration throughout was on a simpler and less expensive scale. Apart from this and the change in plan, the distinguishing feature of the second church was the entire absence of evidences of burning. It is therefore quite certain that the building remained intact until the year 631, when the Byzantine power in Syria and Palestine collapsed under the vigorous onslaughts of the Arab hosts. Even then the church probably was not dismantled but was used, according to the custom of the early Moslems, as a mosque, such of its decorations as were objectionable to them being merely painted out or covered with whitewash. During their use of the building certain persons scratched their names upon the marble floor.

The valley of the Jordan was visited during the succeeding years by many earthquakes, some of them of extreme destructiveness and the building gradually fell into ruin. As early as the end of the eighth century all the marble columns were prostrate, as several Cufic inscriptions were found on them, evidently written when they were lying on the ground.

Image Number: 41638

Among the buildings on the lower terrace, one deserves special mention. We have already seen how the main paved roadway starting from the gate, curved up the north slope to the summit. At the point where it made the first turn southward from the line of the entrance, a smaller street opened off from it, and this was the thoroughfare which gave access to the houses on the lower terrace. Near the gate this was bordered by several storehouses uniform in plan and some buildings with badly broken portions of mosaics. The road rose at a slight incline as it wound around the eastern terrace. Here the outer wall had enclosed a much wider area than now exists. Owing to the steepness of the slope and the insecurity of its foundations it had given away and fallen down the slope, carrying with it portions of the houses. The later Arab enclosing wall which still remains was built on the edge of the terrace as they found it, well inside the older line and it therefore cut away still more of the Byzantine rooms. The Arabs utilized for their own houses much of the earlier masonry, so that the house plans of the preceding period are rather incomplete. It was clear however that the buildings lying between the lane and the terrace edge were as a rule below the level of the roadway and were entered down two or more steps, while the floors of those lying inside at the foot of the upper slope were above this level. At several places were small paved side passages or alleys leading to houses on higher levels.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-928

Image Number: 41811

The narrow lane ended at the gateway of a house of greater size and obviously more importance than any of the buildings bordering the lane. This building and its dependencies occupied the southeast corner of the upper town extending the full width of the east terrace and nearly 150 feet of its length. Of this area about one third was given up to the house itself and the remainder to a large garden. The fine position of this building, easily the best on the entire site, its size and regularity of construction and especially its beautiful mosaic floors indicated that it was certainly the residence of a most important official and I have called it the Bishop’s House.

The walls were of rubble masonry, probably decorated with stucco on which were richly colored scenes, but as the walls were denuded down to a single course, all details of these were lost. Fortunately considerable portions of the mosaic floor still remained and the more desirable pieces have been removed to the University Museum.

The central feature of the plan was a large rectangular court paved with coarse plain white tesserae, without pattern or border. On the east side was a loggia or portico with either two columns or piers for which only the square plinth blocks remained. The floor of the loggia was laid with mosaic consisting of a white ground divided into regular squares with bands of red and yellow. Each square contained a small cross in the centre and the border was quite plain. To the east of the loggia were the corners of two large apartments each with an elaborate patterned floor. Only portions near the wall remained, the rest having vanished during the landslip. In one the field apparently was made up of small and large interlacing circles, enclosed with a scroll border, closely following the pattern in a room of the early basilica on the summit of the hill. The other chamber had a Greek fret border. These motifs were all carried out in deep orange, red and dark gray tesserae, on a plain white ground.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-928

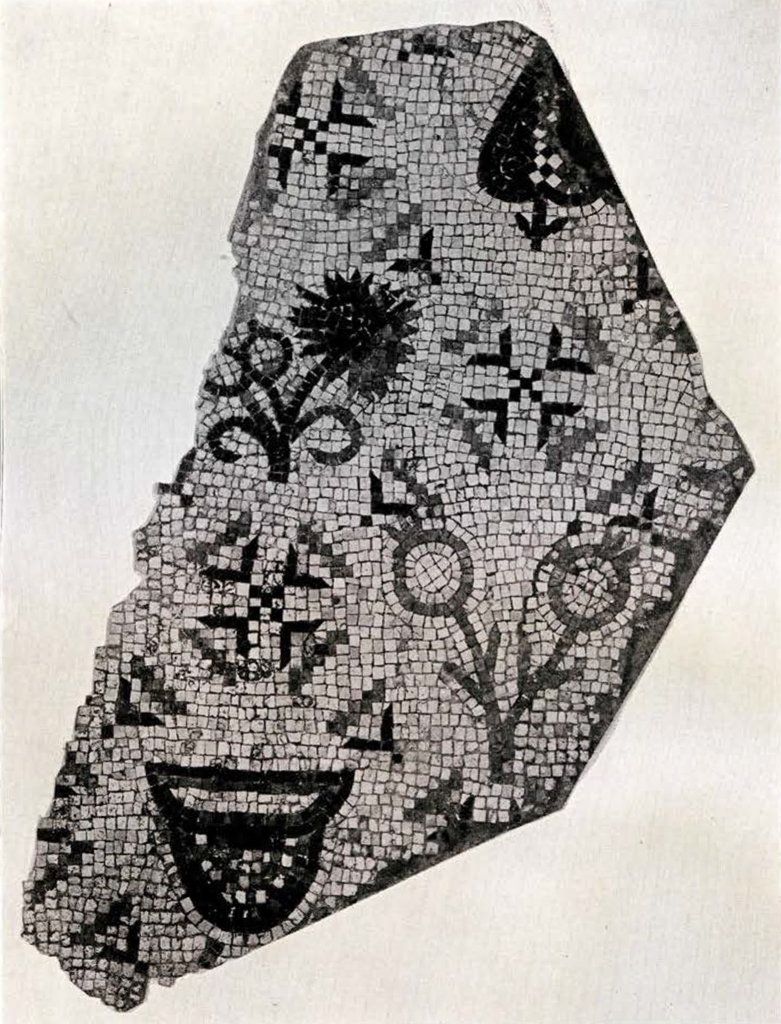

To the south of the court was what may have been the largest and most important chamber in the house. A small door led from it directly into the court, which doubtless had been filled with pleasant greenery, fruit trees and flowers, kept well watered from a deep cistern near the outer wall. The chamber floor was done in mosaic with rather conventional flowers, growing out of jars and with beribboned doves flying between them. While of the simplest design and done only in three colors, the floor was quite attractive. The border was especially elaborate, a series of loops developing one from within the other, forming a chain. The pattern was identical with one discovered in the ruins of an old church excavated on the top of Mount Tabor near Nazareth, and now preserved in the Museum of the Franciscan convent in the latter town. Another room to the east of this and adjoining the loggia was badly wrecked by the collapse of the ceiling and upper walls, the falling stones having made great hollows in the delicate mosaic. The pattern resembled one very common in our modem tiled floors and linoleums, octagons arranged side by side in rows so as to leave small square between them.

The style of these mosaics placed them in the fourth century, and the building therefore was probably erected at the same time as the first great church on the summit. When the latter was burned in the riots of 361 A.D. the Bishop’s House may also have been destroyed, as large areas of the mosaics were burned and disintegrated to a depth of an eighth of an inch.

Museum Object Number: 29-107-930

Image Numbers: 30079, 41810

As I have said, this residence occupied one of the most delightful parts of the city. It lay under the steep eastern slope of the summit, it was sheltered from the severe gales that sweep down the Valley of Jezreel from the Mediterranean during the winter, and in the summer, the towering mass of the church above partly sheltered it from the heat of the afternoon sun. It was at the extreme corner of the hill and from the parapet around the garden one could have looked over the rich green of the orchards far below, bordering the Jalûd and its sister stream that partly encircled the hill. Beyond the low enclosing hills of the city cemetery, the undulating valley of the Jordan was visible for miles, dotted with the numerous smaller towns that owed their existence to the great metropolis towering above them. Here and there the twisting channel of the Jordan itself could be glimpsed where the sunlight glistened upon the water. Still farther away, the lofty. green covered ramparts of the land of Moab formed a continuous background, and at the foot of them, towards the southeast, clearly visible, lay the great rival city of Pella.

It was a peaceful spot. The turmoil and bustle of the crowded city streets were all on the opposite side of the hill. Owing to the impregnability of this quarter all attacks upon the town came from the west, and here too, on the great plain beyond the western walls, took place the many struggles for the possession of the town and its rich environs, and the sound of them would scarcely penetrate to this secluded dwelling.